Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles (also Akhilleus or Achilleus; Ancient Greek: Άχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the central character and greatest warrior of Homer's epic poem Iliad, which takes for its theme, not the War of Troy in its entirety, but specifically the Wrath of Achilles.

Later legends (beginning with a poem by Statius in the first century C.E.) state that Achilles was invulnerable on all of his body except for his heel. These legends state that Achilles was killed in battle by an arrow to the heel, and so an Achilles' heel has come to mean a person's only weakness.

Achilles is also famous for being the most 'handsome' of the heroes assembled at Troy,[1] as well as the fleetest. Central to his myth is his relationship with Patroclus, characterized in different sources as deep friendship or love. The persistence of the Achilles myth witnesses to the human need for heroes, whose skills, courage and endurance spur others to emulate their feats, to draw on hidden resources that sometimes result in super-human effort. The belief that it is possible to transcend limitations, even if death intervenes as it did for Achilles, has in fact stimulated the breaking of records, discoveries, inventions and has contributed to the expansion of our knowledge of the limits and possibilities of human achievements.

Birth

Achilles was the son of the mortal Peleus, king of the Myrmidons in Troy (southeast Thessaly), and the immortal sea nymph Thetis. Zeus and Poseidon had been rivals for the hand of Thetis until Prometheus, the fire-bringer, warned Zeus of a prophecy that Thetis would bear a son greater than his father. For this reason, the two gods withdrew their pursuit and had her wed to Peleus.[2]

As with most mythology there is a tale which offers an alternative version of these events: in Argonautica (iv.760) Hera alludes to Thetis' chaste resistance to the advances of Zeus, that Thetis had been so loyal to Hera's marriage bond that she coolly rejected him.

According to the incomplete poem Achilleis written by Statius in the first century C.E., when Achilles was born Thetis tried to make him immortal by dipping him in the river Styx. However, she forgot to wet the heel she held him by, leaving him vulnerable at that spot. Hence the term Achilles' heel, referring to a weakness despite overall strength. It is not clear if this version of events was known earlier. In another version of this story, Thetis anointed the boy each day with godly ambrosia and each night put him on top of a fire to burn away the mortal parts of his body. She became enraged when interrupted by Peleus, who was unfamiliar with the ritual and abandoned both father and son and returned home to her father, the old man of the sea.[3]

However, none of the sources before Statius makes any reference to this invulnerability. To the contrary, in the Iliad Homer mentions Achilles being wounded: in Book 21 the Paeonian hero Asteropaeus, son of Pelegon, challenged Achilles by the river Scamander. He cast two spears at once; one grazed Achilles' elbow, "drawing a spurt of blood."

Also, in the fragmentary poems of the Epic Cycle in which we can find description of the hero's death, Kùpria (unknown author), Aithiopis by Arctinus of Miletus, Ilias Mikrà by Lesche of Mytilene, Iliou pèrsis by Arctinus of Miletus, there is no trace of any reference to his invulnerability or his famous (Achilles) heel; in the later vase-paintings presenting Achilles' death, the arrow (or in many cases arrows) hit his body.

Peleus entrusted Achilles to Chiron the Centaur, on Mount Pelion, to be raised and educated.[4]

Achilles in the Trojan War

The first two lines of the Iliad read:

- μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος

- οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί' Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε' ἔθηκεν,

- Rage—sing, goddess, the rage of Achilles, the son of Peleus,

- the destructive rage that brought countless griefs upon the Achaeans…

Telephus

When the Greeks left for the Trojan War, they accidentally stopped in Mysia, ruled by King Telephus. In the resulting battle, Achilles gave Telephus a wound that would not heal; Telephus consulted an oracle, who stated that "he that wounded shall heal."

According to other reports in Euripides' lost play about Telephus, he went to Aulis pretending to be a beggar and asked Achilles to heal his wound. Achilles refused, claiming to have no medical knowledge. Alternatively, Telephus held Orestes for ransom, the ransom being Achilles' aid in healing the wound. Odysseus reasoned that the spear had inflicted the wound; therefore, the spear must be able to heal it. Pieces of the spear were scraped off and placed onto the wound and Telephus was healed. This is an example of sympathetic magic.

Cycnus of Colonae

According to traditions related by Plutarch and the Byzantine scholar John Tzetzes, once the Greek ships arrived in Troy, Achilles fought and killed Cycnus of Colonae, a son of the sea god Poseidon. Cycnus was invulnerable, except for his head.[5]

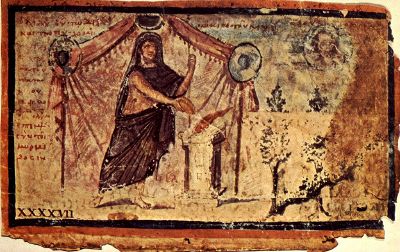

Troilus

According to the Cypria (the part of the Epic Cycle that tells the events of the Trojan War before Achilles' wrath), when the Achaeans desired to return home, they were restrained by Achilles, who afterwards attacked the cattle of Aeneas, sacked neighboring cities (like Pedasus and Lyrnessus, where the Greeks capture the queen Briseis) and killed Tenes, a son of Apollo, as well as Priam's son Troilus in the sanctuary of Apollo Thymbraios.

In Dares Phrygius' Account of the Destruction of Troy,[6] the Latin summary through which the story of Achilles was transmitted to medieval Europe, as well as in older accounts, Troilus was a young Trojan prince, the youngest of King Priam's and Hecuba's five legitimate sons (or according other sources, another son of Apollo).[7] Despite his youth, he was one of the main Trojan war leaders, a "horse fighter" or "chariot fighter" according to Homer.[8] Prophecies linked Troilus' fate to that of Troy and so he was ambushed in an attempt to capture him. Yet Achilles, struck by the beauty of both Troilus and his sister Polyxena, and overcome with lust, directed his sexual attentions on the youth – who, refusing to yield, instead found himself decapitated upon an altar-omphalos of Apollo Thymbraios.[9] Had Troilus lived to adulthood, the First Vatican Mythographer claimed, Troy would have been invincible.[10]

In the Iliad

Homer's Iliad is the most famous narrative of Achilles' deeds in the Trojan War. The Homeric epic, written ca 750 B.C.E., only covers a few weeks of the war, that the ancient Greeks believed had taken place about 500 years earlier. Homer's version of history does not narrate Achilles' death. It begins with Achilles' withdrawal from battle after he is dishonored by Agamemnon, the commander of the Achaean forces. King Agamemnon had taken a woman named Chryseis as his slave, her father Chryses, a priest of Apollo, begged Agamemnon to return her to him. Agamemnon refused and Apollo sent a plague amongst the Greeks. The prophet Calchas correctly determined the source of the troubles, but would not speak unless Achilles vowed to protect him. Achilles did so and Calchas declared Chryses must be returned to her father. Agamemnon consented, but then commanded that Achilles' slave Briseis be brought to replace Chryseis. Angry at the dishonor (and as he says later, because he loved Briseis)[11] and at the urging of Thetis, Achilles refused to fight or lead his Myrmidons alongside the other Greek forces.

As the battle turned against the Greeks, Nestor declared that had Agamemnon not angered Achilles, the Trojans would not be winning and urged Agamemnon to appease Achilles. Agamemnon agreed and sent Odysseus and two other chieftains to Achilles with the offer of the return of Briseis and other gifts. Achilles refused and urged the Greeks to sail home as he was planning to do.

Eventually, Achilles prayed to his mother Thetis, asking her to plead with Zeus to allow the Trojans to push back the Greek forces.

The Trojans, led by Hector, pushed the Greek army back toward the beaches and assaulted the Greek ships. Achilles consented to Patroclus leading the Myrmidons into battle, though Achilles would remain at his camp. Patroclus succeeded in pushing the Trojans back from the beaches, but was killed by Hector before he could lead an assault on the city of Troy.

Achilles versus Hector

After receiving the news of the death of Patroclus from Antilochus, the son of King Nestor, Achilles grieved over his friend and held many funeral games in his honor. His mother Thetis came to comfort the distraught Achilles. She persuaded Hephaestus to make new armor for him, in place of the armor that Patroclus had been wearing which was taken by Hector. The new armor included the Shield of Achilles, described in great detail by the poet.

Enraged over the death of Patroclus, Achilles ended his refusal to fight and took the field killing many men in his rage but always seeking out Hector. Achilles even engaged in battle with the river god Scamander who became angry that Achilles was choking his waters with all the men he killed. The god tried to drown Achilles but was stopped by Hera and Hephaestus. Zeus himself took note of Achilles' rage and sent the gods to restrain him. Finally Achilles found his prey; Achilles chased Hector around the wall of Troy three times before Athena, in the form of Hector's favorite and dearest brother, Deiphobus, persuaded Hector to fight face to face. Achilles got his vengeance, killing Hector with a blow to the neck. He then tied Hector's body to his chariot and dragged it around the battlefield for nine days.

With the assistance of the god Hermes, Priam, Hector's father, went to Achilles' tent and convinced Achilles to permit him to allow Hector his funeral rites. The final passage in the Iliad is Hector's funeral, after which the doom of Troy is just a matter of time.

Penthesilea

Achilles, after his temporary truce with Priam, fought and killed the Amazonian warrior queen Penthesilea.

Memnon, and the death of Achilles

Following the death of Patroclus, Achilles's closest companion was Nestor's son Antilochus. When Memnon of Ethiopia killed Antilochus, Achilles was once again drawn onto the battlefield to seek revenge. The fight between Achilles and Memnon over Antilochus echoes that of Achilles and Hector over Patroclus, except that Memnon (unlike Hector) is also the son of a goddess (like Achilles).

Many Homeric scholars argued that episode inspired many details in the Iliad's description of the death of Patroclus and Achilles' reaction to it. The episode then formed the basis of the cyclic epic Aethiopis, which was composed after the Iliad, possibly in the seventh century B.C.E. The Aethiopis is now lost, except for scattered fragments quoted by later authors.

Quintus of Smyrna also gives us an epic treatment of Memnon's mortal death and the immortality then bestowed upon him by Zeus as well as lyrical description of his countrymen's extreme grief.

As predicted by Hector with his dying breath, Achilles was thereafter killed by Paris — either by an arrow (to the heel according to Statius), or in an older version by a knife to the back while visiting Polyxena, a princess of Troy. In some versions, the god Apollo guided Paris' arrow.

Both versions conspicuously deny the killer any sort of valor owing to the common conception that Paris was a coward and not the man his brother Hector was, and Achilles remains undefeated on the battlefield. His bones are mingled with those of Patroclus, and funeral games are held. He was represented in the lost Trojan War epic of Arctinus of Miletus as living after his death in the island of Leuke at the mouth of the Danube (see below).

Paris was later killed by Philoctetes using the enormous bow of Heracles.

The fate of Achilles' armor

Achilles' armor was the object of a feud between Odysseus and Telamonian Ajax (Achilles' older cousin). They competed for it by giving speeches on why they were the bravest after Achilles and the most deserving to receive it. Odysseus won. Ajax went mad with grief and anguish and vowed to kill his comrades; he started killing cattle or sheep, thinking in his madness that they were Greek soldiers. He then killed himself.

Achilles and Patroclus

Achilles' relationship with Patroclus is a key aspect of his myth. Its exact nature has been a subject of dispute in both the classical period and modern times. In the Iliad, it is clear that the two heroes have a deep and extremely meaningful friendship, but the evidence of a romantic or sexual element is equivocal. Commentators from the classical period to today have tended to interpret the relationship through the lens of their own cultures. Thus, in fifth century B.C.E. Athens the relationship was commonly interpreted as pederastic.

The Cult of Achilles in Antiquity

There was an archaic heroic cult of Achilles on the White Island, Leuce, in the Black Sea off the modern coasts of Romania and Ukraine, with a temple and an oracle which survived into the Roman period.[12]

In the lost epic Aithiopis, a continuation of the Iliad attributed to Arktinus of Miletos, Achilles’ mother Thetis returned to mourn him and removed his ashes from the pyre and took them to Leuce at the mouths of the Danube. There the Achaeans raised a tumulus for him and celebrated funeral games.

Pliny's Natural History (IV.27.1) mentions a tumulus that is no longer evident (Insula Achillis tumulo eius viri clara), on the island consecrated to him, located at a distance of 50 Roman miles from Peuce by the Danube Delta, and the temple there. Pausanias has been told that the island is "covered with forests and full of animals, some wild, some tame. In this island there is also Achilles’ temple and his statue” (III.19.11). Ruins of a square temple 98 feet to a side, possibly that dedicated to Achilles, were discovered by Captain Kritzikly in 1823, but there has been no modern archeology done on the island.

Pomponius Mela tells that Achilles is buried in the island named Achillea, between Boristhene and Ister (De situ orbis, II, 7). And the Greek geographer Dionysius Periegetus of Bithynia, who lived at the time of Domitian, writes that the island was called Leuce "because the wild animals which live there are white. It is said that there, in Leuce island, reside the souls of Achilles and other heroes, and that they wander through the uninhabited valleys of this island; this is how Jove rewarded the men who had distinguished themselves through their virtues, because through virtue they had acquired everlasting honor” (Orbis descriptio, v. 541, quoted in Densuşianu 1913).

The Periplus of the Euxine Sea gives the following details: "It is said that the goddess Thetis raised this island from the sea, for her son Achilles, who dwells there. Here is his temple and his statue, an archaic work. This island is not inhabited, and goats graze on it, not many, which the people who happen to arrive here with their ships, sacrifice to Achilles. In this temple are also deposited a great many holy gifts, craters, rings and precious stones, offered to Achilles in gratitude. One can still read inscriptions in Greek and Latin, in which Achilles is praised and celebrated. Some of these are worded in Patroclus’ honor, because those who wish to be favored by Achilles, honor Patroclus at the same time. There are also in this island countless numbers of sea birds, which look after Achilles’ temple. Every morning they fly out to sea, wet their wings with water, and return quickly to the temple and sprinkle it. And after they finish the sprinkling, they clean the hearth of the temple with their wings. Other people say still more, that some of the men who reach this island, come here intentionally. They bring animals in their ships, destined to be sacrificed. Some of these animals they slaughter, others they set free on the island, in Achilles’ honor. But there are others, who are forced to come to this island by sea storms. As they have no sacrificial animals, but wish to get them from the god of the island himself, they consult Achilles’ oracle. They ask permission to slaughter the victims chosen from among the animals that graze freely on the island, and to deposit in exchange the price which they consider fair. But in case the oracle denies them permission, because there is an oracle here, they add something to the price offered, and if the oracle refuses again, they add something more, until at last, the oracle agrees that the price is sufficient. And then the victim doesn’t run away any more, but waits willingly to be caught. So, there is a great quantity of silver there, consecrated to the hero, as price for the sacrificial victims. To some of the people who come to this island, Achilles appears in dreams, to others he would appear even during their navigation, if they were not too far away, and would instruct them as to which part of the island they would better anchor their ships.” (quoted in Densuşianu)

The heroic cult of Achilles on Leuce island was widespread in Antiquity, not only along the sealanes of the Pontic Sea but also in maritime cities whose economic interests were tightly connected to the riches of the Black Sea.

Achilles from Leuce island was venerated as Pontarches the lord and master of the Pontic (Black) Sea, the protector of sailors and navigation. Sailors went out of their way to offer sacrifice. To Achilles of Leuce were dedicated a number of important commercial port cities of the Greek waters: Achilleion in Messenia (Stephanus Byzantinus), Achilleios in Laconia (Pausanias, III.25,4) Nicolae Densuşianu (Densuşianu 1913) even thought he recognized Achilles in the name of Aquileia and in the north arm of the Danube delta, the arm of Chilia ("Achileii"), though his conclusion, that Leuce had sovereign rights over Pontos, evokes modern rather than archaic sea-law."

Leuce had also a reputation as a place of healing. Pausanias (III.19,13) reports that the Delphic Pythia sent a lord of Croton to be cured of a chest wound. Ammianus Marcellinus (XXII.8) attributes the healing to waters (aquae) on the island.

The Achilleion in Corfu

In the region of Gastouri (Γαστούρι) to the south of the city of Corfu Greece, Empress of Austria Elisabeth of Bavaria also known as Sissi built in 1890 a summer palace with Achilles as its central theme and it is a monument to platonic romanticism. The palace, naturally, was named after Achilles: Achilleion (Αχίλλειον).[13]This elegant structure abounds with paintings and statues of Achilles both in the main hall and in the lavish gardens depicting the heroic and tragic scenes of the Trojan war.

The Name of Achilles

Achilles' name can be analyzed as a combination of ἄχος (akhos) "grief" and λαός (Laos) "a people, tribe, nation, etc." In other words, "Achilles" is an embodiment of the grief of the people, grief being a theme raised numerous times in the Iliad (frequently by Achilles). Achilles' role as the hero of grief forms an ironic juxtaposition with the conventional view of Achilles as the hero of kleos (glory, usually glory in war).

The Greek term Laos has been construed by Harvard professor of Classics Gregory Nagy, following Greek scholar Leonard R. Palmer, to mean a corps of soldiers. With this derivation, the name would have a double meaning in the poem: When the hero is functioning rightly, his men bring grief to the enemy, but when wrongly, his men get the grief of war. The poem is in part about the misdirection of anger on the part of leadership.

Centuries after Homer, his name was turned into the female form of Achillia, attested on a relief from Halicarnassus as the name of a female gladiator fighting 'Amazonia'. Roman gladiatorial games often referenced classical mythology and this seems to reference Achilles' fight with Penthesilea, but give it an extra twist of Achilles being 'played' by a man.

Other stories about Achilles

Some post-Homeric sources claim that in order to keep Achilles safe from the war, Thetis (or, in some versions, Peleus) hides the young man at the court of Lycomedes, king of Skyros. There, Achilles is disguised as a girl and lives among Lycomedes' daughters, perhaps under the name "Pyrrha" (the red-haired girl). With Lycomedes' daughter Deidamia, whom in the account of Statius he rapes, Achilles there fathers a son, Neoptolemus (also called Pyrrhus, after his father's possible alias). According to this story, Odysseus learns from the prophet Calchas that the Achaeans would be unable to capture Troy without Achilles' aid. Odysseus goes to Skyros in the guise of a peddler selling women's clothes and jewelry and places a shield and spear among his goods. When Achilles instantly takes up the spear, Odysseus sees through his disguise and convinces him to join the Greek campaign. In another version of the story, Odysseus arranges for a trumpet alarm to be sounded while he was with Lycomedes' women; while the women flee in panic, Achilles prepares to defend the court, thus giving his identity away.

In Homer's Odyssey, there is a passage in which Odysseus sails to the underworld and converses with the shades. One of these is Achilles, who when greeted as "blessed in life, blessed in death," responds that he would rather be a slave to the worst of masters than be king of all the dead. This has been interpreted as a rejection of his warrior life, but also as indignity to his martyrdom being slighted. Achilles was worshipped as a sea-god in many of the Greek colonies on the Black Sea, the location of the mythical "White Island" which he was said to inhabit after his death, together with many other heroes.

Post-Homeric literature explores a pederastic interpretation of the love between Achilles and Patroclus. By the fifth and fourth centuries, the deep—and arguably ambiguous—friendship portrayed in Homer blossomed into an unequivocal erotic love affair in the works of Aeschylus, Plato, and Aeschines, and seems to have inspired the enigmatic verses in Lycophron's third century Alexandra that claim Achilles slew Troilus in a matter of unrequited love.

The kings of the Epirus claimed to be descended from Achilles through his son. Alexander the Great, son of the Epiran princess Olympias, could therefore also claim this descent, and in many ways strove to be like his great ancestor; he is said to have visited his tomb while passing Troy.

Achilles fought and killed the Amazon Helene. Some also said he married Medea, and that after both their deaths they were united in the Elysian Fields of Hades—as Hera promised Thetis in Apollonius' Argonautica. In some versions of the myth, Achilles has a relationship with his captive Briseis.

Achilles in Greek tragedy

The Greek tragedian Aeschylus (525 B.C.E. – 456 B.C.E.) wrote a trilogy of plays about Achilles, given the title Achilleis by modern scholars. The tragedies relate the deeds of Achilles during the Trojan War, including his defeat of Hector and eventual death when an arrow shot by Paris punctures his heel. Extant fragments of Myrmidons and other Aeschylean fragments have been assembled to produce a workable modern play.

Another lost play by Aeschylus, The Myrmidons, focused on the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus; only a few lines survive today.

The tragedian Sophocles also wrote a play with Achilles as the main character, The Lovers of Achilles. Only a few fragments survive.

Achilles in Greek philosophy

The philosopher Zeno of Elea (fifth century B.C.E.) centered one of his paradoxes on an imaginary footrace between "swift-footed" Achilles and a tortoise, in which he "proved" that Achilles could not catch up to a tortoise with a head start, and therefore that motion and change were impossible. Here and elsewhere, Zeno was probably pointing out that logical paradoxes should not be taken as definitive guides to understanding the world.

Achilles in later art

Drama

- Achilles is portrayed as a former hero, who has become lazy and devoted to the love of Patroclus, in William Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida.

Fiction

- Achilles appears in the novels Ilium and Olympos by science fiction author Dan Simmons.

- Achilles the novel by Elizabeth Cook

- Achilles appears in Dante's "The Inferno."

- The Wrath of Achilles is a starship in 'Gene Rodenberry's Andromeda'

- Achilles appears in the novel Inside The Walls of Troy, with emphasis on his relationship to Polyxena

- Achilles appears in the book trilogy Troy by the late heroic fantasy novelist David Gemmell

- Achilles is featured heavily in the novel The Firebrand by Marion Zimmer Bradley

Film

The role of Achilles has been played by:

- Gordon Mitchell in "Achilles" (1962)

- Piero Lulli in Ulysses (1955)

- Riley Ottenhof in Something about Zeus (1958)

- Stanley Baker in Helen of Troy (1956)

- Arturo Dominici in La Guerra di Troia (1962)

- Derek Jacobi [voice] in Achilles (Channel Four Television) (1995)

- Steve Davislim in La Belle Hélène (TV, 1996)

- Joe Montana (actor) in Helen of Troy (TV, 2003)

- Brad Pitt in Troy (2004)

Television

- In the animated Canadian television series Class of the Titans, (2005) the character Archie is descended from Achilles and has inherited both his vulnerable heel and part of his invincibility.

Music

Achilles has frequently been mentioned in music.

- "Achilles Last Stand," by Led Zeppelin; from the album Presence, 1976, Atlantic Records.

- Achilles is referred to in Bob Dylan's song, "Temporary Like Achilles."

- "Achilles' Revenge" is a song by Warlord.

- Achilles Heel is an album by the indie rock band Pedro the Lion.

- Achilles and his heel are referenced in the song "Special K" by the rock band Placebo.

- "Achilles' Heel" is a song by the UK band Toploader.

- "Achilles" is a song by the Colorado-based power metal band Jag Panzer, from the album Casting the Stones.

- Achilles is referenced in the Indigo Girls song "Ghost."

- Song by Melbourne band Love Outside Andromeda called "Achilles (All 3)."

- "Achilles, Agony & Ecstasy In Eight Parts," by Manowar; from the album The Triumph of Steel, 1992, Atlantic Records.

- Although not mentioned by name, "Citadel" (about the Siege of Troy) by The Crüxshadows mentions Paris' arrow 'landing true'.

- "Achilles' Wrath," a concert piece by Sean O'Loughlin.

Namesakes

- HMNZS Achilles was a Leander class cruiser which served with the Royal New Zealand Navy in World War II. She became famous for her part in the Battle of the River Plate, alongside HMS Ajax and HMS Exeter.

Notes

- ↑ Plato, "Symposium". Written 360 B.C.E., Translated by Benjamin Jowett. MIT Classics. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 755-768; Pindar, Nemean 5.34-37, Isthmian 8.26-47; Poeticon astronomicon (ii.15)

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library Sir James George Frazer (ed.) 3.13.6. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Hesiod, Catalogue of Women, fr. 204.87-89 MW; Iliad 11.830-832.

- ↑ Plutarch, Greek Questions 28; Tzetzes, On Lycophron.

- ↑ Carlos Parada, Dares' account of the destruction of Troy, Greek Mythology Link. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.151.

- ↑ Iliad 24.257. Cf. Virgil, Aeneid 1.474–478.

- ↑ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca Epitome 3.32.

- ↑ The motif, however, is older and found already in Plautus, Bacchides, 953ff.

- ↑ Iliad 9.334-343.

- ↑ Guy Hedreen, "The Cult of Achilles in the Euxine." Hesperia 60(3) (July 1991): 313-330.

- ↑ Corfu Achillion Palace Greeka.com. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Classical

- Apollodorus. Bibliotheca, III, xiii, 5-8

- Apollodorus. Epitome III, 14-V, 7

- Apollonius Rhodius. Argonautica IV, 783-879

- Dante, Aligheri. The Divine Comedy, Inferno, V.

- Hesiod. Catalogue of Women. English version, The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women: Constructions and Reconstructions, Edited by Richard Hunter. University of Cambridge, 2008. ISBN 0521069823

- Homer. Iliad. translated by Robert Fagles, Bernard MacGregor, Walker Knox. New York NY: Viking, 1990. ISBN 978-0670835102

- Homer. Odyssey XI, translated by Robert Fagles. NY: Viking, 1996 ISBN 978-0670821624

- Ovid. Metamorphoses XI, 217-265; XII, 580-XIII, 398.

- Ovid, and R. J. Tarrant. Metamorphoses. Scriptorum classicorum bibliotheca Oxoniensis. Oxonii: E Typographeo Clarendoniano, 2004. ISBN 978-0198146667

- Ovid. Heroides III by Ovid, and Daryl Hine. Ovid's Heroines: A Verse Translation of the Heroides. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991 ISBN 978-0300050936

- Plutarch. Moralia, Volume IV, Roman Questions. Greek Questions. Greek and Roman Parallel Stories. On the Fortune of the Romans. On the Fortune or the Virtue … in Wisdom? (Loeb Classical Library No. 305) Frank C. Babbitt, (Translator) 1936. ISBN 0674993365

Secondary

- Cook, Elizabeth. Achilles. New York: Picador USA, 2002. ISBN 978-0312311100

- Hamilton, Edith. Mythology. (original 1942) NY: Little, Brown & Co, 1998. ISBN 978-0316341141

- Monsacré, Hélène. Les larmes d'Achille. Le héros, la femme et la souffrance dans la poésie d'Homère. Paris: Albin Michel, 1984. ISBN 978-2226021632

- Nagy, Gregory. The Best of The Acheans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry, rev. ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1999. ISBN 978-0801822001

- Nagy, Gregory. "The Name of Achilles: Questions of Etymology and 'Folk Etymology." Illinois Classical Studies 19 (1994): 3-9.

- Warren, Johansson, "Achilles." Encyclopedia of Homosexuality, (ed.) Wayne R. Dynes, Garland Publishing, 1990. ISBN 978-0824065447

External links

All links retrieved October 2, 2023.

- Who was Achilles? The British Museum

- Achilles Gallery of Ancient Art

- Achilles - The Trojan War Hero Greek Mythology

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.