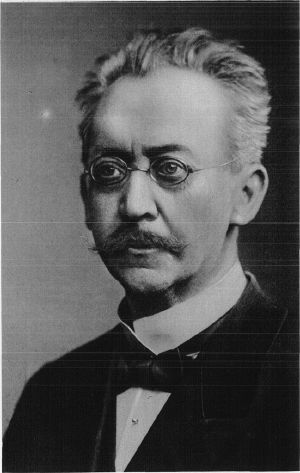

Adolf von Harnack (May 7, 1851 – June 10, 1930), was a German theologian and prominent church historian who pioneered the effort to free Christianity from what he called its "acute Hellenization" that had happened through the early church's development in the Roman Empire. Although best known for his achievements in theology and church history, Harnack was also a major force in German scientific circles, serving as the a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and other major scientific institutes.

Harnack produced many important religious publications from 1873-1912. He traced the influence of Hellenistic philosophy on early Christian writings and called on Christians to question the authenticity of doctrines that arose in the Christian church. He argued that Christianity must free itself from theological dogmatism and seek, through rigorous study of the history of Christian doctrine, to return to the religion of the earliest church, i.e., the gospel of Jesus himself. Thus, he also rejected the Gospel of John as unhistorical and criticized the Apostles' Creed as adding doctrinal points never intended by Jesus or the earliest leaders of the Christian church.

Harnack's voluminous writings remain foundational reading for serious students of early church history and the development of Christian theology. His liberal theological position, characteristic of nineteenth-century theology since Immanuel Kant, may have led to his support of Kaiser Wilhelm II's war policy in 1914, but his call for returning to the gospel of Jesus deserves the attention of anyone who seeks to know what Jesus' original intention was two thousand years ago.

Biography

Harnack was born at Tartu (then Dorpat) in Livonia, which was then a province of Russia, now in Estonia. His father, Theodosius Harnack, held a professorship of pastoral theology at Tartu. Adolf himself studied at the University of Tartu (1869–1872) and later at the University of Leipzig, where he took his degree. Soon after this (1874) he began lecturing on such special subjects as Gnosticism and the Apocalypse. In an age when the critical study of the Bible was a cutting-edge subject at Europe's leading universities, his lectures attracted considerable attention, and in 1876 he was appointed as a professor at Leipzig. In the same year he began the publication, in conjunction with Oscar Leopold von Gebhardt and Theodor Zahn, of an edition of the works of the Apostolic Fathers, an edition of which appeared in 1877.

Three years later, Harnack was called to the University of Giessen as professor of church history. There he collaborated with Gebhardt in editing an occasional periodical dedicated to studies in New Testament and patristics (the works of the Church Fathers). In 1881 he published a work on monasticism and became joint editor with Emil Schürer of the Theologische Literaturzeitung.

In 1885 Harnack published the first volume of his monumental work, Lehrbuch der Dogmengeschichte (History of Dogma). The book built on the work of earlier German biblical scholars such as Ferdinand Christian Baur and Albrecht Ritschl, and also pioneered new ground in applying the historico-critical method to the study of the New Testament and early church history. In this work, Harnack detailed the historical process of the rise of church doctrine in the early church and its later development from the fourth century down to the Protestant Reformation. He held that Christian doctrine and Greek philosophy were closely intermingled. The resultant theological system, he said, included many beliefs and practices that did not originate with the historical Jesus or his Apostles and were not authentically Christian.

According to Harnack, Protestants are not only free, but bound, to criticize the traditional propositions of Christian theology. Protestantism, he held, should be understood not only as the attempt to break away from archaic Catholic traditions and authority, but also as a rejection of other inauthentic dogma and a return to the pure faith that characterized the original church.

In 1886 Harnack was called to teach at the University of Marburg. In 1888 he was invited to teach at the prestigious University of Berlin. This appointment was strongly opposed by the official Evangelical Church of Prussia because of Harnack's views that Protestantism had not yet gone far enough in returning to the authentic traditions of earliest Christianity. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and the recently appointed emperor, Kaiser William II, overruled the opposition, clearing the way for Harnack's acceptance. In 1890 he became a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.

Despite being rejected for any office in the Church of Prussia, Harnack exercised a broad influence among Protestant churchmen throughout Europe. His careful academic methods and teaching ability won the enthusiastic support of his students, many of whom rose to positions of leadership in their respective churches. In Berlin, Harnack was drawn into a controversy on the Apostles' Creed. His view was that the creed contains both too much and too little to be a satisfactory test for candidates for ordination as ministers. He preferred a briefer declaration of faith which could be rigorously applied to all.

Harnack continued writing, and in 1893 he published a history of early Christian literature down to Eusebius of Caesarea entitled The History of Ancient Christian Literature. A collection of his popular lectures, Das Wesen des Christentums (What is Christianity?) appeared in 1900. One of his later historical works, published in English as The Mission and Expansion of Christianity in the First Three Centuries (1904-1905), was followed by several important New Testament studies on Luke the Physician, 1907; and The Sayings of Jesus (1908).

He was ennobled—thus entitled to use the "von" before his last name—in March 1914. After World War I broke out, he was summoned to draft Kaiser Wilhelm's "Call to the German People" ("An das deutsche Volk") of August 6, 1914. Like many ostensibly liberal professors in Germany, Harnack welcomed the First World War and signed a public manifesto in September 1914 together with many other intellectuals including a dozen of theologians, endorsing Germany's war aims. It was this statement that Karl Barth, a student of Harnack, cited as a major impetus for his disillusionment in liberal theology.

Harnack was one of the moving spirits in the foundation, in 1911, of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, today known as the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science. He became its first president. Harnack retired from his position at the University of Berlin in 1921, but continued to be influential in both theological and scientific circles.

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society's activities, which were much constrained by the First World War, were guided by Harnack to become a major vehicle for overcoming the isolation of German academics in the war's aftermath. The Society's flagship conference center in Berlin, which opened in 1929, was named in his honor as the Harnack House. Harnack died June 10, 1930, in Berlin.

Theology

One of the distinctive characteristics of Harnack's work was his insistence on absolute freedom in the study of church history and the New Testament. He held that there could be no "taboo" areas of research that could not be critically examined. However, he distrusted of speculative theology, whether orthodox or liberal. Following the Ritschilian tradition, he had a special interest in practical Christianity as a religious life rather than as a system of theology. Some of his addresses on social matters were published in a book entitled Essays on the Social Gospel (1907).

Although the four gospels had been regarded as canonical since Irenaeus in the second century, Harnack—like earlier German scholars—rejected the Gospel of John as without historical value regarding Jesus' actual life. He wrote:

The fourth Gospel, which does not emanate or profess to emanate from the apostle John, cannot be taken as an historical authority in the ordinary meaning of the word. The author of it acted with sovereign freedom, transposed events and put them in a strange light, drew up the discourses himself, and illustrated great thoughts by imaginary situations. Although, therefore, his work is not altogether devoid of a real, if scarcely recognizable, traditional element, it can hardly make any claim to be considered an authority for Jesus’ history; only little of what he says can be accepted, and that little with caution.[1]

Also, according to Harnack, Christian dogma, which he believed has resulted from the "acute Hellenization of the church,"[2] incorporating Greek concepts such as essence, substance, and being, is far from the essence of Christianity, which is nothing but the practical gospel of Jesus Christ himself. This gospel of Jesus, to which we must go back, contained three things, which "are each of such a nature as to contain the whole, and hence it can be exhibited in its entirety under any one of them": 1) "the kingdom of God and its coming"; 2) "God the Father and the infinite value of the human soul"; and 3) "the higher righteousness and the commandment of love."[3]

Harnack, therefore, did not appreciate ontological Christology, for example, that deals with the person of Christ in terms of the metaphysical unity of the divine and human natures. So, he provocatively ended up saying: "The Gospel, as Jesus proclaimed it, has to do with the Father only and not with the Son."[4] By this, however, he never meant that Jesus stood outside his gospel, but that he was important and beneficial for us as the person who knew the Father better than anyone else: "But no one had ever yet known the Father in the way in which Jesus knew Him, and to this knowledge of Him he draws other men’s attention, and thereby does 'the many' an incomparable service."[4]

Harnack saw Jesus as a liberal religious reformer who was opposed by the legalistic tradition of the Pharisees. His view that Jesus' thought was original and had little in common with the Pharisees, however, was criticized as a lapse in his usually fine scholarship by the German Reform Jewish theologian Leo Baeck. Baeck pointed out that the Pharisees were a diverse group that included liberal as well as conservative elements, and that some of Jesus' teachings appeared to have been borrowed from great Pharisaic sages such as Hillel the Elder.

Harnack was skeptical about the miracles reported in the Bible, but argued that Jesus and other biblical figures may well have performed acts of faith healing. "That the earth in its course stood still; that a she-ass spoke; that a storm was quieted by a word, we do not believe, and we shall never again believe; but that the lame walked, the blind saw, and the deaf heard will not be so summarily dismissed as an illusion."[5]

Harnack was not reticent to examine afresh the writings of ancient Christian authors considered heretical in church tradition. He held that these writers had much to teach modern Christians about the development of church doctrine, and even suggested that some of their teachings should not be considered heretical today. He further believed that many fundamental propositions of Christian doctrine—such as the Virgin Birth, the Incarnation, and the Trinity—were not present in the earliest church and need to be re-examined by modern Christians in light of the historical origins.

Signing the manifesto of September 1914

In September 1914, Harnack was one of the ninety-three German intellectuals who signed a manifesto to the cultured world ("An die Kulturwelt"), announcing their support of the Kaiser's war policy. It stated, among others, that it is not true that Germany caused the war, as was alleged. Harnack apparently defended this point all his life. A question is quite often raised as to why a Christian theologian with such high caliber would be part of the spearhead of such a manifesto. The answer can probably be found in his overconfidence about the accomplishment of German culture in Christendom. According to him, in the history of the development of world culture, the three nations of Germany, England, and America have been placed at the apex of humanity with their solemn obligation to civilize the rest of the world, and especially Germany has made a powerful development, which however has not necessarily been welcomed by old powers such as England. To Harnack, England's reluctance to accept the cultural development of Germany was the main cause of the war, and any legal discussion about who attacked first is secondary.

The manifesto stated that "we shall carry on this war to the end as a civilized nation, to whom the legacy of a Goethe, a Beethoven, and a Kant, is just as sacred as its own hearths and homes."[6] In fact, it was from Kant that the nineteenth-century tradition of Kulturtheologie (theology of culture) to synthesize God and human culture started; and it was carried on especially by German theologians such as Schleiermacher, Hegel, Ritschl, and Harnack, although it was also followed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in England and Walter Rauschenbusch in America. Harnack believed that this earthly cultural accomplishment especially in Germany was completely in accord with the gospel of Jesus concerning the kingdom of God where the infinite value of the human soul in front of God the Father can be determined by the practice of love. However, this equation of German culture with the ideal kingdom of God may be questioned. According to a recently published article on this subject, Harnack's misjudgment was due to his prophetic vision of an ideal nation where law plays no part at all in favor of the spirit of the completely embodied love of God in humans: "The dangers of love without law."[7]

Legacy

Harnack was one of the most prolific and stimulating of modern critical scholars. He raised up a whole generation of teachers who carried his ideas and methods throughout the whole of Germany and beyond. He was the leading historian of early Christianity—indeed of Christianity in general—in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Harnack's impact went beyond the fields of church history and theology through his affiliation with the Prussian Academy of Sciences, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, etc. His greatest contribution, however, remains his pioneering writings in the field of historical dogmatics and church history. His basically liberal theological position, which was typical of nineteenth-century Christianity since Kant and Schleiermacher, and which tended to identify the earthly cultural accomplishment especially in Germany with Jesus' vision of the kingdom of God, may have led to his support of the Kaiser's war policy in 1914. But, his deep insights into what he called the "acute Hellenization" of Christianity have become influential and widespread. His call for going back to the original gospel of Jesus himself, whatever it may have been, as the essence of Christianity beyond its Hellenized dogma deserves the attention of anyone who seeks to know what Jesus originally wanted to teach 2000 years ago.

Notes

- ↑ Adolf Harnack, "What is Christianity?" Lecture II. Christian classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ↑ Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma, vol. 1, trans. Neil Buchanan (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1902), 48ff.

- ↑ Adolf Harnack, "What is Christianity?" Lecture III. Christian classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Harnack, "What is Christianity?" Lecture VIII. Christian classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ↑ Harnack, "What is Christianity?" Lecture II. Christian classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Manifesto of the Ninety-Three German Intellectuals." Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ↑ J.C. O'Neill, "Adolf von Harnack and the Entry of the German State into War, July-August 1914," Scottish Journal of Theology 55 (2002): 1-18.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources

- (With Wilhelm Herrmann). Essays on the Social Gospel, Translated by G. M. Craik and Maurice A. Canney. London: Williams & Norgate, 1907. OCLC 2537155

- History of Dogma. 7 vols. Translated by Neil Buchanan. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1896-1905.

- Luke the Physician: The Author of the Third Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, Translated by John Richard Wilkinson; Edited by William Douglas Morrison. reprint ed Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007. ISBN 0548125058

- The Mission and Expansion of Christianity in the First Three Centuries, Translated and edited by James Moffatt. New York: Harper, 1962. OCLC 387274

- What Is Christianity? Book Tree, 2006. ISBN 158509272X

Secondary sources

- Chadwick, Henry. The Early Church, Revised ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993. ISBN 0140231994

- Glick, Garland Wayne. The Reality of Christianity; A Study of Adolf Von Harnack As Historian and Theologian.. New York: Harper & Row, 1967. OCLC 1178490

- Harnack, Adolf von, and Martin Rumscheidt. Adolf Von Harnack: Liberal Theology at Its Height. The Making of modern theology. London: Collins, 1989. ISBN 978-0005991305

- Nainggolan, Binsar. The Social Involvement of Adolf Von Harnack: A Critical Assessment. Theorie und Forschung, Bd. 827. Regensburg: Roderer, 2005. ISBN 978-3897834828

- O'Neill, J.C. "Adolf von Harnack and the Entry of the German State into War, July-August 1914." Scottish Journal of Theology 55 (2002):1-18.

- Pauck, Wilhelm. Harnack and Troeltsch; Two Historical Theologians. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968. OCLC 386682

- Zahn-Harnack, Agnes von. Adolf Von Harnack. Berlin: W. de Gruyter, 1951. OCLC 16772031

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved June 15, 2023.

- Adolf Harnack – www.ccel.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.