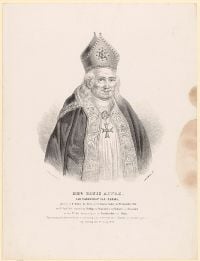

Denis-Auguste Affre (September 27, 1793– June 27, 1848), archbishop of Paris from 1840, was born at Saint Rome, in the department of Tarn. The Archbishop is mainly remembered due to the circumstances surrounding his death, when he tried to pacify the insurgents during the insurrection of June 1848 following the declaration of the Second Republic, and was shot while speaking to the crowd, dying almost immediately after. He was a staunch defender of academic freedom, a view that at the time clashed with that of the King of the French, Louis-Philippe.

His ministry and episcopacy was set in the context of post-Revolution France, and the struggle between religion and the state. As the bourgeois gained more influence, first under Napoleon Bonaparte and then under the regime of Louis-Philippe, the conditions of the working class deteriorated. As a champion of the proletariat, Affre's sympathies were more in tune with the original ideals of the revolution, which intended to replace rule by the few with that of the many.

Biography

Denis-Auguste Affre was born at Saint Rome-de-Tam in France into a devout Catholic family. Ar the age of 14 he entered the Saint-Sulpice Seminary, which at the time was directed by his uncle, Denis Boyer. Affre excelled in his studies for the priesthood, and after graduation in 1818 he remained at the Seminary as professor of dogmatic theology at Nantes. Upon ordination, he became a member of the Sulpician Community. After filling a number of important ecclesiastical offices as vicar-general of Luçon (1821), Amiens (1823), and then Paris (1834) he was nominated and appointed archbishop of Paris in 1840.

Political context

The political context during which Affre exercised his ministry and his eight years as a bishop was a turbulent period for Christianity, especially for the Roman Catholic Church in France. Before the French Revolution, the French Catholic Church was the "most flourishing Catholic church in the world."[1] The Catholic church was the largest land-owner and exercised considerable political influence, especially in such field as public morality and education. The revolution swept away an absolute monarchy and it soon targeted the absolutist claims of the Church as well. Churches were closed, priests and nuns killed, or exiled, and the Church's land was confiscated by the State to pay for its debts. Monasteries were dissolved, as were Cathedral chapters in an attempt to make the Church more democratic. The Civil Constitution of the Church (1790) made priests into civil servants, and the church as instrument of the state. The church lost the right to levy its own taxes. Not all clergy accepted this arrangement and many refused to take the required oath of loyalty.

For the first decade of post-revolution France when the working-class dominated the new political system, the Church was unpopular, associated with conservatism and absolutism. When Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power and "restored a bourgeois France," he negotiated a Concordat with the Pope (1802). This represented a compromise that enabled the Church to regain some of the influence it had lost, which was popular with the bourgeois.[1] Under the Concordat, priests were still paid by the state and required to swear the oath of loyalty. The Catholic Church was recognized as the religion of the majority of the French but the religious freedom introduced by the Revolution remained, so Jews and Protestants retained their rights. The Pope would be allowed to remove bishops. However, they would still be nominated by the State. The Church also relinquished claims to property that had been confiscated by the state. What is usually described as "anti-clericalism," however, had become, and remains, part of the social ethos.

The Reign of Louis-Philippe, 1830-1848

After Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo (1815), a constitutional monarchy was established. In 1830, Louis-Philippe became the so-called citizen King. However, he retained quite a degree of personal power and one of the first Acts of his administration was to ban discussion about the political legitimacy of the constitutional monarchy. Archbishop Affre was at odds with the Louis-Philippe administration on several issues. As Archbishop, he made education a priority and wanted greater freedom ((liberté d'enseignement) for teachers and students in public as well as in church-related schools. Public education since the Revolution was dominated by secularism, which meant that teachers could not teach content associated with religious conviction. The absolutism of the the ancien régime (old regime) was replaced by one of the secular state.

Affre, Education and Social Reform

As Archbishop, Affre established the École des Carmes (1845), which became the Institut Catholique de Paris in 1875. He also supported improved conditions for the working class, campaigning with other "Catholic liberals in promoting educational and social reform." [2] The conditions of the proletariat had worsened with the restoration of Bourgeoisie power. Unemployment was high, food was in short supply and no welfare system was in place to assist the most needy.

Although he was opposed to the government during the debate on education, he took no part in politics. However, when the Second Republic was established in 1848 (which lasted until the start of Napoleon III's Second Empire in 1852) he welcomed this because it promised increased democracy. Affre pledged formal support to the acting President, even though items had been removed from one of his churches by insurgents.

Support for the Second Republic

While the Second Republic was in the process of assuming the reigns of government, many public servants went unpaid and in June 1848 they rioted in the streets of Paris. Affre was led to believe that his personal interference might be restore peace between the soldiery and the insurgents.

Accordingly, in spite of the warning of General Cavaignac, he mounted the barricade at the entrance to the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, bearing a green branch as a sign of peace. He had spoken only a few words when the insurgents, hearing some shots, and assuming that they had been betrayed, opened fire on the national guard. Struck by a stray bullet, the archbishop fell.

Death

He was removed to his palace, where he died on June 27.

Next day the National Assembly issued a decree expressing their great sorrow on account of his death. The Archbishop's public funeral took place on July 7. Affre had told General Cavaignac, "My life is of little value, I will gladly risk it." [3]

Affre was buried in the Chapel of Saint-Denis in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. His heart was removed and preserved in the chapel of the Carmelite Seminary, which he had founded.

Publications

The archbishop wrote several treatises of considerable value. In his Essai sur les hieroglyphes egyptiens (Paris, 1834), he showed that Champollion's system was insufficient to explain the hieroglyphics. Other publications include Traité de l'administration temporelle des paroisses (Paris, 1827; 11th ed., 1890), Traité de la propriété des biens ecclésiastiques (Paris, 1837) and Introduction philosophique à l'étude du Christianisme (Paris, 5th ed., 1846). He was founder-editor of the periodical La France chrétienne.

Legacy

Affre was a Christian leader who had to operate, if he was to operate all all, within the political context of his day. His appointment as Archbishop of Paris took him from relative obscurity into the full view of the Parisian public. While in the initial days of the French Revolution, the Church was regarded as the defender of privilege, under Affre, it was the defender of the proletariat. He was a staunch supporter of social reforms and of academic freedom. His ideals may have been closer to those of the revolutionaries than to those of the subsequent bourgeois dominated regimes of Napoleon and of the so-called citizen-King. His attempt to pacify the crowd testifies to his courage, even though it led to his premature death.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Owen Chadwick, A History of Christianity (NY: Barnes & Noble, 2005, ISBN 0760773327), 240.

- ↑ James Chastain, Affre, Denis-Auguste University of Ohio. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ↑ Francis W. Grey, Denis-Auguste Affre The Catholic Encyclopedia (1907) Retrieved March 10, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alazard, L. Denis-Auguste Affre, archeveque de Paris. Paris: J. Vrin, 1971.

- Chadwick, Owen. A History of Christianity. NY: Barnes & Noble, 2005. ISBN 0760773327

- Ricard, Antonio. Les grands eveques de l'eglise de France au XIXe siècle. Lille: Société de Saint-Augustin, Desclée, De Brouwer, first published in 1893-1894.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External Links

All links retrieved July 26, 2022.

- Denis-Auguste Affre at Britannica online

- Denis-Auguste-Affre at The Catholic Encyclopedia

- Denis-Auguste Affre at Find-A-Grave

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.