| Ainu |

|---|

Group of Ainu people, 1904 photograph. |

| Total population |

| 50,000 people with half or more Ainu ancestry 150,000 Japanese people with some Ainu ancestry

Pre-Japanese era: ~50,000, almost all pure Ainu |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Languages |

| Ainu is the traditional language. According to research by Alexander Vovin, in 1996 only 15 fluent speakers remained, and the last speaker of the Sakhalin dialect had died in 1994. Most Ainu today are native speakers of the Japanese or Russian language. (Note that the Aini language spoken in China is unrelated). *Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. ISBN 1-55671-159-X. |

| Religions |

| Animism, some are members of the Russian Orthodox Church |

| Related ethnic groups |

Modern genetics has proven they are East Asians. They are usually grouped with the non-Tungusic peoples of Sakhalin, the Amur river valley, and the Kamchatka peninsula:

|

Ainu (アイヌ, International Phonetic Alphabet : /ʔáınu/) are an ethnic group indigenous to Hokkaidō, northern Honshū (Japan), the Kuril Islands, much of Sakhalin, and the southernmost third of the Kamchatka peninsula. The word aynu means "human" (as opposed to kamuy, divine beings) in the Hokkaidō dialects of the Ainu language. The Ainu once lived on all four major Japanese islands, but over the centuries were pushed northwards by the Japanese people. Eventually the Japanese took control of their traditional lands, and during the Meiji period, Japanese policies became increasingly aimed at assimilating the Ainu, outlawing their language and restricting them to farming as part of a program to "unify" the Japanese national character.

Traditional Ainu dress was a robe spun from the bark of the elm tree and decorated with geometric designs, with long sleeves, folded round the body and tied with a girdle of the same material. The men never shaved and had full beards and mustaches, and men and women alike cut their hair level with the shoulders, trimmed semicircularly behind. The Ainu lived in reed-thatched huts, without partitions and with a fireplace in the center, and never ate raw fish or flesh, always either boiling or roasting it, using wild herbs for flavor. Intermarriage and cultural assimilation have made the traditional Ainu almost extinct; of the 24,000 people on Hokkaido who are still considered Ainu, only a few are pure bloods and very few speak Ainu. Recent genetic studies have suggested that ancient Ainu may have been among the peoples who came from Asia to settle in North America.

Name

Their most widely known ethnonym is derived from the word aynu, which means "human" (particularly as opposed to kamuy, divine beings) in the Hokkaidō dialects of the Ainu language; Emishi, Ezo or Yezo (蝦夷) are Japanese terms, which are believed to derive from the ancestral form of the modern Sakhalin Ainu word enciw or enju, also meaning "human"; and Utari (ウタリ, meaning "comrade" in Ainu) is now preferred by some members.

Origins

Some commentators believe that the Ainu derive from an ancient proto-Northern Mongoloid peoples that may have occupied parts of Central and East Asia before the Han expansion (see Jomon people). Various other Mongoloid indigenous peoples, such as the Ryukyuans, are thought to be closely related to them. The Ainu people have a legend that says, "The Ainu lived in this place a hundred thousand years before the Children of the Sun came."

The prevailing mythology in Japan has portrayed the Ainu as a race of "noble savages," a proud but reclusive culture of hunter-gatherers. This mythology became a useful defense for the Japanese expropriation of Ainu lands. In fact, the Ainu were farmers as well as hunter-gatherers from the earliest centuries of the Common Era.[1]

Genetic testing of the Ainu people has shown them to belong mainly to Y-DNA haplogroup D.[2] The only places outside of Japan in which Y-haplogroup D is common are Tibet and the Andaman Islands.[3] About one in eight Ainu men have been found to belong to Haplogroup C3, which is the most common Y-chromosome haplogroup among the indigenous populations of the Russian Far East and Mongolia. Some researchers have speculated that this minority of Haplogroup C3 carriers among the Ainu may reflect a certain degree of unidirectional genetic influence from the Nivkhs, with whom the Ainu have long-standing cultural interactions.[2] According to Tanaka, et al. (2004), their mtDNA lineages mainly consist of haplogroup Y (21.6 percent) and haplogroup M7a (15.7 percent).[4]

Some have speculated that the Ainu may be descendants of the same prehistoric race that also produced indigenous Australian peoples. In Steve Olson's book, Mapping Human History, page 133, he describes the discovery of fossils dating back 10,000 years, representing the remains of the Jomon people, a group whose facial features more closely resemble those of the indigenous peoples of New Guinea and Australia. After a new wave of immigration, probably from the Korean Peninsula, some 2,300 years ago, of the Yayoi people, the pure-blooded Jomon were pushed into northern Japan. Genetic data suggests that the modern Japanese people are descended from both the Yayoi and the Jomon.

American Continent Connection

In the late twentieth century, a speculation arose that people of the group ancestral to the Ainu may have been among the first to settle North America. This theory is based largely on skeletal and cultural evidence among tribes living in the western part of North America and certain parts of Latin America. It is possible that North America had several peoples among its early settlers and that the Ainu may have been one of them, perhaps even the first. The best-known example supporting this theory is probably Kennewick Man.

Groundbreaking genetic mapping studies by Cavalli-Sforza have shown a sharp gradient in gene frequencies centered in the area around the Sea of Japan, and particularly in the Japanese Archipelago, that distinguishes these populations from others in the rest of eastern Asia and most of the American continent. This gradient appears as the third most important genetic movement (in other words, the third principal component of genetic variation) in Eurasia (after the "Great expansion" from the African continent, which has a cline centered in Arabia and adjacent parts of the Middle East, and a second cline that distinguishes the northern regions of Eurasia and particularly Siberia from regions to the south), which would make it consistent with the early Jomon period, or possibly even the pre-Jomon period.[5]

History

The Ainu once lived on all four major Japanese islands, but over the centuries they were pushed northwards by the Japanese people. At first, the Japanese people and the Ainu living in the north were equals in a trade relationship. Eventually the Japanese started to dominate the relationship, and soon established large settlements on the outskirts of Ainu territory. As the Japanese moved north and took control of their traditional lands, the Ainu often acceded, but there was occasional resistance, such as the wars of 1457, 1669, and 1789, all of which were lost by the Ainu. (Notable Ainu revolts include Shakushain's Revolt and the Menashi-Kunashir Battle.) During the Meiji period, Japanese policies became increasingly aimed at assimilating the Ainu, outlawing their language and restricting them to farming on government-provided plots. Ainu were also made near-slaves in the Japanese fishing industry. The name of the island of Hokkaido, which had been called Ezo or Ezo-chi during the Edo period was changed to “Hokkaido” during the Meiji Restoration as part of a program to "unify" the Japanese national character under the aegis of the Emperor and diminish the local identity and autonomy of the different regions of Japan. During the Meiji period, the Ainu were given the status of “former aboriginals” but continued to suffer official discrimination for some time.

In the past, Ainu affairs were administered by hereditary chiefs, three in each village, and for administrative purposes the country was divided into three districts, Saru, Usu, and Ishikari. The district of Saru was in control of the other regions, though the relations between their respective inhabitants were not close and intermarriages were avoided. Judicial functions were not entrusted to the hereditary chiefs; an indefinite number of a community's members sat in judgment upon its criminals. Capital punishment did not exist, nor did the community resort to imprisonment; beating was considered a sufficient and final penalty. However, murder, was punished by cutting off the nose and ears or severing the tendons of the feet. As Japanese citizens, the Ainu are now governed by Japanese laws and judged by Japanese tribunals.

Traditional Ainu were round-eyed, dark-haired and short in stature, with abundant body and facial hair in contrast to their Mongoloid neighbors. They lived by hunting, trapping and fishing and some agriculture. Intermarriage and cultural assimilation have made the traditional Ainu almost extinct. Of the 24,000 people on Hokkaido who are still considered Ainu, only a few are purebloods and very few speak Ainu or practice the religion. The exact number of Ainu is not known as many Ainu hide their origin or are not even aware of it, because their parents have kept it from them so as to protect their children from racial discrimination.

In 1997 a law was passed to provide funds for research and promotion of Ainu culture. Today, many Ainu dislike the term Ainu and prefer to identify themselves as Utari (comrade in the Ainu language). In official documents both names are used.

Geography

For historical reasons (primarily the Russo-Japanese War), nearly all Ainu live in Japan. There is, however, a small number of Ainu living on Sakhalin, most of them descendants of Sakhalin Ainu who were evicted and later returned. There is also an Ainu minority living at the southernmost area of the Kamchatka Peninsula and on the Kurile Islands. However, the only Ainu speakers remaining (besides perhaps a few partial speakers) live solely in Japan. There, they are concentrated primarily on the southern and eastern coasts of the island of Hokkaidō.

Due to intermarriage with the Japanese and ongoing absorption into the predominant culture, few living Ainu settlements exist. Many "authentic Ainu villages" advertised in Hokkaido are simply tourist attractions.

Language

The Ainu language is significantly different from Japanese in its syntax, phonology, morphology, and vocabulary. Although there have been attempts to demonstrate a relationship between the two languages, the majority of modern scholars deny that the relationship goes beyond contact and the mutual borrowing of words between Japanese and Ainu. No attempt to show a relationship between Ainu and any other language has gained wide acceptance, and Ainu is currently considered to be a language isolate.

Culture

Traditional Ainu culture is quite different from Japanese culture. After a certain age, the men never shaved and had full beards and moustaches. Men and women alike cut their hair level with the shoulders at the sides of the head, but trimmed it semicircularly behind. The women tattooed their mouths, arms, clitorides, and sometimes their foreheads, starting at the onset of puberty. The soot deposited on a pot hung over a fire of birch bark was used for color. Traditional Ainu dress was a robe spun from the bark of the elm tree and decorated with geometric designs. It had long sleeves, reached nearly to the feet, and was folded round the body and tied with a girdle of the same material. Women also wore an undergarment of Japanese cloth. In winter the skins of animals were worn, with leggings of deerskin and boots made from the skin of dogs or salmon. Both sexes were fond of earrings, which are said to have been made of grapevine in former times, as were bead necklaces called tamasay, which the women prized highly.

Their traditional cuisine consisted of the flesh of bear, fox, wolf, badger, ox or horse, as well as fish, fowl, millet, vegetables, herbs, and roots. The Ainu never ate raw fish or flesh, but always either boiled or roasted it. Notable dishes were kitokamu, a sausage flavored with wild garlic; millet porridge; ohaw or rur, a savory soup based on a stock flavored with fish or animal bones and kelp, and containing solid ingredients such as meat, fish, venison, vegetables and wild edible plants; and munini-imo (munin ("fermented" in Ainu) + imo ("potatoes" in Japanese), savory pancakes made with potato flour.

Traditional Ainu habitations were reed-thatched huts, the largest being 20 feet (six meters) square, without partitions and with a fireplace in the center. There was no chimney, but only a hole at the angle of the roof; there was one window on the eastern side and two doors. The house of the village head was used as a public meeting place when one was needed. Instead of using furniture, they sat on the floor, which was covered with two layers of mats, one of rush, the other of flag; and for beds they spread planks, hanging mats around them on poles, and employing skins for coverlets. The men used chopsticks when eating; the women had wooden spoons. Ainu cuisine is not commonly eaten outside Ainu communities; there are only a few Ainu restaurants in Japan, all located in Tokyo and Hokkaidō.

Religion

The Ainu are traditionally animists, believing that everything in nature has a kamuy (spirit or god) inside it. In the hierarchy of the kamuy, the most important is grandmother earth (fire), then kamuy of the mountain (animals), then kamuy of the sea (sea animals), followed by everything else. The Ainu have no priests by profession. The village chief performs whatever religious ceremonies are necessary; ceremonies are confined to making libations of rice beer, uttering prayers, and offering willow sticks with wooden shavings attached to them. These sticks are called Inau (singular) and nusa (plural), and are placed on an altar used to sacrifice the heads of killed animals. The most important traditional ceremony of the Ainu involved the sacrifice of a bear. The Ainu people give thanks to the gods before eating and pray to the deity of fire in time of sickness. They believe their spirits are immortal, and that their spirits will be rewarded hereafter by ascending to kamuy mosir (Land of the Gods).

Some Ainu in the north are members of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Creation Myth of the Ainu

The cosmology of the Ainu people consists of six heavens and six hells where gods, demons, and animals lived. Demons lived in the lower heavens. Amongst the stars and the clouds lived the lesser gods. In highest heaven lived Kamui, the creator God, and his servants. His realm was surrounded by a mighty metal wall and the only entrance was through a great iron gate. Kamui made this world as a vast round ocean resting on the backbone of an enormous trout. This fish sucks in the ocean and spits it out again to make the tides; when it moves it causes earthquakes.

One day Kamui looked down on the watery world and decided to make something of it. He sent down a water wagtail to do the work. By fluttering over the waters with its wings and by trampling the sand with its feet and beating it with its tail, the wagtail created patches of dry land. In this way islands were raised to float upon the ocean. When the animals who lived up in the heavens saw how beautiful the world was, they begged Kamui to let them go and live on it, and he did. But Kamui also made many other creatures especially for the world. The first people, the Ainu, had bodies of earth, hair of chickweed, and spines made from sticks of willow. Kamui sent Aioina, the divine man, down from heaven to teach the Ainu how to hunt and to cook.

Sport

The Ainu excel at many competitive physical activities. Due to their taller physical build, the Ainu have outshone the ethnic Japanese in typically Western sports like baseball, soccer, and track and field events. The athletic feats of the Ainu people are celebrated throughout Asia.[7].

Institutions

There are many organizations of Ainu trying to further their cause in different ways. An umbrella group, the Hokkaido Utari Association, of which most Hokkaido Ainu and some other Ainu are members, was originally controlled by the government with the intention of speeding Ainu assimilation and integration into the Japanese nation, but now operates mostly independently of the government and is run exclusively by Ainu.

Subgroups

- Tohoku Ainu (from Honshū, no known living population)

- Hokkaido Ainu

- Sakhalin Ainu

- Kuril Ainu (no known living population)

- Kamchatka Ainu (extinct since pre-historic times)

- Amur Valley Ainu (probably none remain)

Notes

- ↑ Gary Crawford, NOVA Online - Island of the Spirits - Origins of the Ainu, PBS. A map of Japan showing the fateful site of Sakushukotoni-gawa on Hokkaido. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Tajima Atsushi et al., Genetic origins of the Ainu inferred from combined DNA analyses of maternal and paternal lineages, Journal of Human Genetics, ISSN 1434-5161. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ↑ J. D. McDonald, worldwide distribution of Y chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA, haplogroups. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ↑ M. Tanaka, et al., "Mitochondrial Genome Variation in Eastern Asia and the Peopling of Japan." Genome Research, 14 (2004): 1832-1850. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ↑ Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi and Alberto Piazza, "The synthetic maps suggest a previously unsuspected center of expansion from the Sea of Japan but cannot indicate dates. This development could be tied to the Jomon period, but one cannot entirely exclude the pre-Jomon period and that it might be responsible for a migration to the Americas. A major source of food in those pre-agricultural times came from fishing, then as now, and this would have limited, for ecological reasons, the area of expansion to the coastline, perhaps that of the Sea of Japan, but also father along the Pacific Coast", The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton University Press, 1994, ISBN 0691087504), 253.

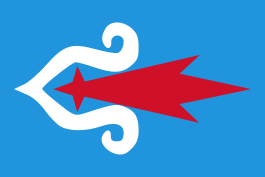

- ↑ Independence movements and aspirant peoples (Japan) Flag of Ainu People by Pascal Gross. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ W. Fitzhugh, Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2004, ISBN 0295979127), 364-367.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca, Paolo Menozzi, and Alberto Piazza. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0691087504

- Fitzhugh, W. Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2004. ISBN 0295979127

- Kayano, Shigeru. Our Land Was a Forest: An Ainu Memoir, Translated by Kyoko Selden and Lili Selden. Foreword by Mikiso Hane. Transitions—Asia and Asian America series. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994. ISBN 9780813317076 ISBN 9780813318806

- Tanaka, M., et al. "Mitochondrial Genome Variation in Eastern Asia and the Peopling of Japan." Genome Research, 14 (2004): 1832-1850. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- Walker, B. L. The conquest of Ainu lands: ecology and culture in Japanese expansion, 1590-1800. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001. ISBN 0520227360

- Weiner, M. Japan's minorities: the illusion of homogeneity. Sheffield Centre for Japanese Studies/Routledge series. London: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 9780415130080 ISBN 9780415152181

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

- Ainu, Spirit of a Northern People. Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institute.

- Nippon Utari Kyokai (Japanese).

- Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Ainu in Samani, Hokkaido.

- Origins of the Ainu. PBS NOVA.

- Sea-Girt Yezo: Glimpses at Missionary Work in North Japan, by John Batchelor 1902 account of life and Anglican missionary work on Hokkaidō.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.