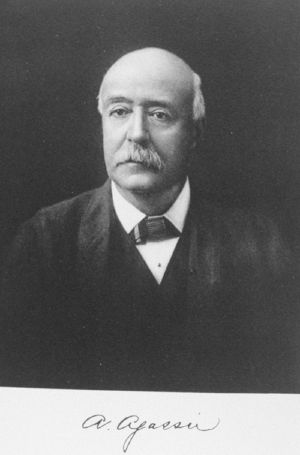

Alexander Emanuel Agassiz

Alexander Emanuel Agassiz (December 17, 1835 – March 27, 1910), was an American scientist and engineer. After some involvement in mining operations, Agassiz became well known for his work in marine zoology, and oceanography. He was influential in the development of modern systematic zoology, and made important studies of marine life of the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean aboard the HMS Challenger with the Challenger Expedition.

His name is honored with the Alexander Agassiz Medal established in 1913. The award is given annually by the National Academy of Sciences for an original contribution in the science of oceanography. It was established by Sir John Murray, "founder of modern oceanography," in honor of his friendship with Alexander Agassiz. Agassiz, who wanted to improve the quality of human life, believed that an eternal reality underlies the natural order.

Early Life

Agassiz was born in Neuchatel, Switzerland. He was the only son of Louis Agassiz, a prominent naturalist, and Cecile Braun, renowned artist. He was educated mostly in Baden, Germany, where his mother and sisters lived with his uncle. Agassiz learned to speak French and German and first became interested in science after meeting famous biologist, Theodore Von Shiebold.

The elder Agassiz took his son and emigrated to the United States in 1849. He graduated from Harvard University in 1855, subsequently studying engineering and chemistry, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree at the Lawrence scientific school from the same institution in 1857. He was appointed as Assistant in the United States Coast Survey in 1859, and worked in California and Washington Territory. One year later, in 1860, Agassiz married Anna Russell.

Career

Agassiz became fascinated in and over time became a specialist in marine ichthyology, but devoted much time to the investigation, superintendence and exploitation of mines. He maintained a close relationship and made a hobby of marine biology.

E. J. Hulbert, a friend of Agassiz's brother-in-law, Quincy Adams Shaw, had discovered a rich copper lode known as the Calumet conglomerate on the Keweenaw Peninsula of Lake Superior. He persuaded Shaw and Agassiz, along with a group of friends, to purchase a controlling interest in the mines, which later became known as the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company based in Calumet, Michigan. Up until the summer of 1866, Agassiz worked as an assistant in the Harvard University museum of natural history that his father founded. That summer, he took a trip to see the copper mines for himself. Following his inspection, Agassiz agreed to serve as treasurer of the enterprise.

During the winter of 1866 and early 1867, mining operations began to falter due to the difficulty of extracting copper from the conglomerate. Hulbert sold his interests in the mines and had moved on to other ventures. But Agassiz refused to give up hope for the mines, and he returned to the mines in March of 1867 with his wife and young son. At that time, Calumet was a remote settlement, virtually inaccessible during the winter and very far removed from civilization even during the summer. With insufficient supplies at the mines, Agassiz struggled to maintain order, while in Boston, Shaw was saddled with debt and the collapse of their interests. Shaw salvaged the enterprise by obtaining financial assistance from John Simpkins, the selling agent, for the enterprise to continue operations.

Agassiz continued to live at Calumet, making gradual progress in stabilizing the mining operations. With the infusion of capital from Shaw's efforts, he was able to leave the mines under the control of a general manager and return to Boston in 1868 before winter closed Lake Superior to navigation.

The mines continued to prosper and in May 1871, several mines were consolidated to form the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company with Shaw as its first president. In August 1871, Shaw "retired" to the board of directors and Agassiz became president, a position he held until his death, 29 years later.

Marine Biologist

Agassiz was a major factor in the mine's continued success and visited the mines twice a year. He innovated by installing a giant engine, known as the Superior, which was able to lift 24 tons of rock from a depth of 4,000 feet. He also built a railroad and dredged a channel to navigable waters. However, after a time the mines did not require his full-time year-round attention and he returned to his interests in natural history at Harvard.

Out of his copper fortune, he gave some $500,000 to Harvard for its museum of comparative zoology and other purposes.

He assisted Charles Wyville Thomson in the examination and classification of the collections of the Challenger Expedition from 1870 to 1872. Aboard the HMS Challenger, borrowed from the Royal Navy and refitted for scientific purposes, Thomson and Agassiz led a scientific expedition that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography. The result was the Report Of The Scientific Results of the Exploring Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-76, which, among many other discoveries, cataloged 4,000 previously unknown species of animal. John Murray, who supervised the publication, described the report as "the greatest advance in the knowledge of our planet since the celebrated discoveries of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries." Following that, Agassiz wrote the Review of the Echini (2 vols., 1872–1874).

In 1875 he surveyed Lake Titicaca, Peru, examined the copper mines of Peru and Chile, and made a collection of Peruvian antiquities for the Museum of Comparative Zoology, of which he was curator from 1874 to 1885.

Agassiz believed that his investigation of the natural world would contribute to humanity's ability to craft a better future, to move humanity onto a different and higher level of existence. He was inspired by the conviction that nature testifies to a reality, to something eternal, that underlies everything that is. One biographer writes that:

- His religious feelings seemed to be best expressed as a yearning after a higher and better life, which he held would become more attainable and more pronounced as mankind advanced in scientific knowledge.[1]

From 1877 until 1880 he took part in the three dredging expeditions of the steamer Blake of the United States Coast Survey, and presented a full account of them in two volumes (1888).

Legacy

Of his other writings on marine zoology, most are contained in the bulletins and memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. In 1865, he published (with Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, his step-mother) Seaside Studies in Natural History, a work at once exact and stimulating, and in 1871 Marine Animals of Massachusetts Bay.

He served as a president of the National Academy of Sciences, which since 1913 has awarded the Alexander Agassiz Medal in his memory.

He died in 1910 while aboard the White Star Line passenger ship SS Adriatic.

Works

- (with Elizabeth Cary Agassiz) Seaside Studies in Natural History (1865)

- North American Acalephs, (1865)

- Marine Animals of Massachusetts Bay (1817)

- Revision of the Echini (2 vols., 1872–1874)

- North American Starfishes, (1877)

- Report on the Echini of the Challenger Expedition, (1881)

- Explorations of Lake Titicaca

- List of the Echinoderms

- Three Cruises of the Blake (1888)

- Pacific Coral Reefs

- Coral Reefs of the Maldives

- Panamic Deep Sea Echini

Notes

- ↑ "Alexander Agassiz: His Life and Scientfic Work." Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. Vol LIV, No 3. Alexander Agassiz: His Life and Scientific Work Retrieved November 27, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dupree, Hunter. Alexander Agassiz. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970.

- Elman, Robert. First in the field: America's pioneering naturalists. New York: Mason/Charter 1977. ISBN 9780884054993

- Tiner, John Hudson. 100 scientists who shaped world history. 100 series. San Mateo, Calif: Bluewood Bks, 2000. ISBN 9780912517391

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.