Alfred the Great

Alfred (also Ælfred from the Old English: Ælfrēd) (c. 849 – October 26, 899) is often considered to be the founder of the English nation. As king of the southern Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex from 871 to 899, Alfred is noted for his defense of the kingdom against the Danish Vikings. Alfred is the only English King to be awarded the epithet 'the Great' (although not English, Canute the Great was another King of England given this title by the Danes) and was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself 'King of the Anglo-Saxons'.

One reason for Alfred's greatness was the magnanimity with which he treated his enemies, the Danes, after defeating them at the Battle of Edington. Realizing that it was impossible to drive the Vikings out, and believing it immoral to massacre them, Alfred converted them to Christianity and accepted their presence on English soil. By thus loving his enemy he laid the basis for the eventual assimilation of the Danes, who became English, sharing their language, faith and customs. His rare example—compare the centuries-old enmities between the English and the Celts (Scots and Welsh) who until today have never forgiven the English for invading their lands—is one reason why Alfred is called the "Father of the English people".

Alfred was a devoted Christian and a learned man, who encouraged education, codified England's laws, and promoted literacy and learning at a time when many among the nobility had little time for these pursuits. Historian Jacob Abbott comments that Alfred the Great laid, "broad and deep… the enormous superstructure" on which the British Empire would be raised, and describes him as an "honest, conscientious, disinterested and far-seeing statesman" whose concern was for his people, not personal power.[1]

Childhood

Alfred was born sometime between 847 and 849 at Wantage in the present-day ceremonial county of Oxfordshire (though historically speaking in the historic county of Berkshire). He was the fifth and youngest son of King Ethelwulf of Wessex, by his first wife, Osburga.

At five years of age, Alfred is said to have been sent to Rome where, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, he was confirmed by Pope Leo IV who "anointed him as king." Victorian writers interpreted this as an anticipatory coronation in preparation for his ultimate succession to the throne of Wessex. However, this coronation could not have been foreseen at the time, since Alfred had three living elder brothers. A letter of Leo IV shows that Alfred was made a 'consul' a misinterpretation of this investiture, deliberate or accidental, could explain later confusion.[2] It may also be based on Alfred later having accompanied his father on a pilgrimage to Rome and spending some time at the court of Charles the Bald, King of the Franks, around 854–855. In 858, Ethelwulf died and Wessex was ruled by three of Alfred's brothers in succession.

Bishop Asser, who chronicled the life of this beloved king around the 888, tells the story about how as a child Alfred's mother offered a volume of Anglo-Saxon poetry to the first of her children able to read it. This story may be true, or it may be a myth designed to illustrate the young Alfred's love of learning.

Royal prince and military commander

During the short reigns of his two eldest brothers, Ethelbald and Ethelbert, Alfred is not mentioned. However, with the accession of the third brother, Ethelred I, in 866, the public life of Alfred began. It is during this period that Asser applies to him the unique title of 'secundarius,' which may indicate a position akin to that of the Celtic tanist, a recognized successor closely associated with the reigning monarch. It is possible that this arrangement was sanctioned by the Witenagemot, to guard against the danger of a disputed succession should Ethelred fall in battle. The arrangement of crowning a successor as diarch is well-known among Germanic tribes, such as the Swedes and Franks, with whom the Anglo-Saxons had close ties.

In 868, Alfred, fighting beside his brother Ethelred, unsuccessfully attempted to keep the invading Danes out of the adjoining kingdom of Mercia. For nearly two years, Wessex itself was spared attacks. However, at the end of 870, the Danes arrived in his home land. The year that followed has been called "Alfred's year of battles." Nine general engagements were fought with varying fortunes, though the place and date of two of the battles have not been recorded. In Berkshire, a successful skirmish at the Battle of Englefield, on December 31, 870, was followed by a severe defeat at the Siege and Battle of Reading, on January 5, 871, and then, four days later, a brilliant victory at the Battle of Ashdown on the Berkshire Downs, possibly near Compton or Aldworth. Alfred is particularly credited with the success of this latter conflict. However, later that month, on January 22, the English were again defeated at Basing and, on the following March 22 at 'Merton' (perhaps Marden in Wiltshire or Martin in Dorset). Two unidentified battles may also have occurred in between.

King at War

In April 871, King Ethelred died, most probably from wounds received at the Battle of Merton. Alfred succeeded to the throne of Wessex and the burden of its defense, despite the fact that Ethelred left two young sons. Although contemporary turmoil meant the accession of Alfred—an adult with military experience and patronage resources—over his nephews went unchallenged, he remained obliged to secure their property rights. While he was busy with the burial ceremonies for his brother, the Danes defeated the English in his absence at an unnamed spot, and then again in his presence at Wilton in May. Following this, peace was made and, for the next five years, the Danes were occupied in other parts of England. However, in 876, under their new leader, Guthrum, the enemy slipped past the English army and attacked Wareham in Dorset. From there, early in 877, and under the pretext of talks, they moved westwards and took Exeter in Devon. There, Alfred blockaded them and, a relieving fleet having been scattered by a storm, the Danes were forced to submit. They withdrew to Mercia, but, in January 878, made a sudden attack on Chippenham, a royal stronghold in which Alfred had been staying over Christmas, "and most of the people they reduced, except the King Alfred, and he with a little band made his way by wood and swamp, and after Easter he made a fort at Athelney, and from that fort kept fighting against the foe." (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle)

A popular legend tells how, when he first fled to the Somerset Levels, Alfred was given shelter by a peasant woman who, unaware of his identity, left him to watch some cakes she had left cooking on the fire. Preoccupied with the problems of his kingdom, Alfred accidentally let the cakes burn and was taken to task by the woman upon her return. Upon realizing the king's identity, the woman apologised profusely, but Alfred insisted that he was the one who needed to apologize. From his refuge at Athelney, a marshy island near North Petherton, Alfred was able to organize an effective resistance movement. In 1693 a gold and enamelled jewel bearing the inscription, Aelfred Mec Heht Gewyrcan - Alfred ordered me to be made - was found on a farm in Athelney suggesting these stories may be more than fanciful legends.

Another story relates how Alfred disguised himself as a minstrel in order to gain entry to Guthrum's camp and discover his plans. He realized that the Danes were low on supplies. So he quietly called up the local militia from Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire to meet him at Egbert's Stone. Alfred led the army and met the Danish host at Edington. Traditionally it was assumed to be Edington in Wiltshire, but new evidence suggests it was Edington in Somerset. The Danes broke and fled to Chippenham. Though tired, Alfred and the Saxon army pursued them and laid siege to their camp. After two weeks the cold, hungry Danes surrendered. Undiscouraged by their past treachery, Alfred took pity on his enemies and fed them. Alfred,

had the wisdom to realize that the sword, though powerful to defend, could settle nothing permanently, and that only the conquest of the heart could endure. And though he and his people had suffered terribly from the invaders, he was too magnanimous to seek revenge and too wise to suppose that he could expel them altogether.[3]

Instead, as Asser recounts, he invited Guthrum to become a Christian and, "stood godfather to him and raised him from the holy font." Guthrum, and 29 of his chief men, received baptism when they signed the Treaty of Wedmore. As a result, England became split in two: the southwestern half kept by the Saxons and the northeastern half including London, thence known as the Danelaw, by the Vikings. By the following year (879), not only Wessex, but also Mercia, west of Watling Street, was cleared of the invaders. Although the Danes and Saxons fought each other many more times,

Alfred's peace making at Wedmore marked a turning point in English history. It made it possible for Danes and Englishmen - the injurers and the injured - to live together in a single island, and opened the way to the former's conversion and civilization.[4]

The tide had turned. For the next few years there was peace, the Danes being kept busy in Europe. A landing in Kent in 884 or 885 though successfully repelled, encouraged the East Anglian Danes to rise up. The measures taken by Alfred to repress this uprising culminated in the taking of London in 885 or 886, and an agreement was reached between Alfred and Guthrum, known as the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. Once more, for a time, there was a lull, but in the autumn of 892 or 893, the Danes attacked again. Finding their position in Europe somewhat precarious, they crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. They entrenched themselves, the larger body at Appledore, Kent, and the lesser, under Haesten, at Milton also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them, indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonization. Alfred, in 893 or 894, took up a position from where he could observe both forces. While he was in talks with Haesten, the Danes at Appledore broke out and struck northwestwards. They were overtaken by Alfred's eldest son, Edward, and defeated in a general engagement at Farnham in Surrey. They were obliged to take refuge on an island in the Hertfordshire Colne, where they were blockaded and ultimately compelled to submit. The force fell back on Essex and, after suffering another defeat at Benfleet, coalesced with Haesten's force at Shoebury.

Alfred had been on his way to relieve his son at Thorney when he heard that the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes were besieging Exeter and an unnamed stronghold on the North Devon shore. Alfred at once hurried westward and raised the Siege of Exeter. The fate of the other place is not recorded. Meanwhile the force under Haesten set out to march up the Thames Valley, possibly with the idea of assisting their friends in the west. But they were met by a large force under the three great ealdormen of Mercia, Wiltshire and Somerset, and made to head off to the northwest, being finally overtaken and blockaded at Buttington. An attempt to break through the English lines was defeated. Those who escaped retreated to Shoebury. Then after collecting reinforcements they made a sudden dash across England and occupied the ruined Roman walls of Chester. The English did not attempt a winter blockade, but contented themselves with destroying all the supplies in the neighborhood. Early in 894 (or 895), want of food obliged the Danes to retire once more to Essex. At the end of this year and early in 895 (or 896), the Danes drew their ships up the Thames and Lea and fortified themselves 20 miles above London. A direct attack on the Danish lines failed, but later in the year, Alfred saw a means of obstructing the river so as to prevent the egress of the Danish ships. The Danes realized that they were out-maneuvered. They struck off north-westwards and wintered at Bridgenorth. The next year, 896 (or 897), they gave up the struggle. Some retired to Northumbria, some to East Anglia. Those who had no connections in England withdrew to the Continent. The long campaign was over.

Reorganization

After the dispersal of the Danish invaders, Alfred turned his attention to the increase of the royal navy, partly to repress the ravages of the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes on the coasts of Wessex, partly to prevent the landing of fresh invaders. This is not, as often asserted, the beginning of the English navy. There had been earlier naval operations under Alfred. One naval engagement was certainly fought under Aethelwulf in 851, and earlier ones, possibly in 833 and 840. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, however, does credit Alfred with the construction of a new type of ship, built according to the king's own designs, "swifter, steadier and also higher/more responsive than the others." However, these new ships do not seem to have been a great success, as we hear of them grounding in action and foundering in a storm. Nevertheless both the Royal Navy and the United States Navy claim Alfred as the founder of their traditions. The first vessel ever commissioned into the Continental Navy, precursor to the United States Navy, was named the Alfred.

Alfred's main fighting force, the fyrd, was separated into two, "so that there was always half at home and half out" (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle). The level of organization required to mobilize his large army in two shifts, of which one was feeding the other, must have been considerable. The complexity which Alfred's administration had attained by 892 is demonstrated by a reasonably reliable charter whose witness list includes a thesaurius, cellararius and pincerna—treasurer, food-keeper and butler. Despite the irritation which Alfred must have felt in 893, when one division, which had "completed their call-up," gave up the siege of a Danish army just as Alfred was moving to relieve them, this system seems to have worked remarkably well on the whole.

One of the weaknesses of pre-Alfredian defenses had been that, in the absence of a standing army, fortresses were largely left unoccupied, making it very possible for a Viking force to quickly secure a strong strategic position. Alfred substantially upgraded the state of the defenses of Wessex, by erecting fortified burghs (towns) throughout the kingdom. These permanently garrisoned strongholds could keep the Vikings at bay until the army could destroy them. He peopled them with his veterans. Overcoming the national prejudice against urban life, Alfred founded 25 towns in the last 20 years of his reign including Oxford and Shaftesbury. They acted as a shield frustrating the Viking Grand Army when it arrived. Other European rulers copied this strategy which enabled Christian western Christendom to survive the Viking attacks.

Alfred is thus credited with a significant degree of civil reorganization, especially in the districts ravaged by the Danes. Even if one rejects the thesis crediting the 'Burghal Hidage' to Alfred, what is undeniable is that, in the parts of Mercia acquired by Alfred from the Vikings, the shire system seems to have been introduced for the first time. This is probably what prompted the legend that Alfred was the inventor of shires, hundreds and tithings. Alfred's care for the administration of justice is testified both by history and legend; and he has gained the popular title 'protector of the poor.' Of the actions of the Witangemot, we do not hear very much under Alfred. He was certainly anxious to respect its rights, but both the circumstances of the time and the character of the king would have tended to throw more power into his hands. The legislation of Alfred probably belongs to the later part of the reign, after the pressure of the Danes had relaxed. He also paid attention to the country's finances, though details are lacking.

Foreign Relations

Asser speaks grandiosely of Alfred's relations with foreign powers, but little definite information is available. His interest in foreign countries is shown by the insertions which he made in his translation of Orosius. He certainly corresponded with Elias III, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, and possibly sent a mission to India. Contact was also made with the Caliph in Baghdad. Embassies to Rome conveying the English alms to the Pope were fairly frequent. Around 890, Wulfstan of Haithabu undertook a journey from Haithabu on Jutland along the Baltic Sea to the Prussian trading town of Truso. Alfred ensured he reported to him details of his trip.

Alfred's relations to the Celtic princes in the western half of Britain are clearer. Comparatively early in his reign, according to Asser, the southern Welsh princes, owing to the pressure on them of North Wales and Mercia, commended themselves to Alfred. Later in the reign the North Welsh followed their example, and the latter co-operated with the English in the campaign of 893 (or 894). That Alfred sent alms to Irish as well as to European monasteries may be taken on Asser's authority. The visit of the three pilgrim 'Scots' (i.e., Irish) to Alfred in 891 is undoubtedly authentic. The story that he himself in his childhood was sent to Ireland to be healed by Saint Modwenna, though mythical, may show Alfred's interest in that island.

Law: Code of Alfred, Doom book

Alfred the Great’s most enduring work was his legal Code, reconciling the long established laws of the Christian kingdoms of Kent, Mercia and Wessex. These formed Alfred’s ‘Deemings’ or Doom book (Book of Laws). In it Alfred admonished, "Doom very evenly! Do not doom one doom to the rich; another to the poor! Nor doom one doom to your friend; another to your foe!" Winston Churchill observed that Alfred blended these with the Mosaic Code, the Christian principles of Celto-Brythonic Law and old Anglo-Saxon customs.[5] F. N. Lee traced the parallels between Alfred’s Code and the Mosaic Code.[6] [7] Churchill stated that Alfred’s Code was amplified by his successors and grew into the body of Customary Law administered by the Shire and The Hundred Courts. The main principles of English Common law Thomas Jefferson concluded, "existed while the Anglo-Saxons were yet pagans, at a time when they had never yet heard the name of Christ pronounced or that such a character existed." Alfred's laws were the basis of the Charter of Liberties, issued by Henry I of England 1100. The Norman kings were forced again and again to respect this body of law under the title the "Laws of Edward the Confessor," the last Anglo-Saxon king. The signing of the Magna Carta in 1215 was just another example of the English determination to make their rulers obey the law.

Religion and Education

The history we have of the Church in the time of Alfred is patchy. That it had been very vital is beyond dispute. There were thriving monasteries in Lindisfarne, Jarrow, Glastonbury, Canterbury and Minster. They had trained and sent out missionaries not only to the English tribes but also to central Europe, the most famous being Saint Boniface, advisor to Charlemagne. However, the Vikings had preyed on these monasteries, seizing their gold and silver, enslaving their novices and burning the buildings. Although Alfred founded two or three monasteries and brought foreign monks to England, there was no general revival of monasticism under him.

At the start of his reign there was reputed to be hardly a single clerk in Wessex who could understand the Latin mass he intoned. However, Alfred had a passion for education and set himself to teach his people himself. Nearly half of his revenue he devoted to educational purposes. He concerned himself with the training of craftsmen and he brought over foreign scholars such as Grimbald and John the Saxon from Europe and Bishop Asser from South Wales. He founded a court school to teach the sons of thanes and freemen to read and write which created the first literate lay nobility in Europe: In a letter to the bishops he said,

All the sons of freemen who have the means to undertake it should be set to learning English letters, and such as are fit more advanced education and are intended for high office should be taught Latin also.

He even made their fathers take lessons too!

It was characteristic of Alfred that before trying to teach others he taught himself first. He worked with his craftsmen designing houses. He invented a candle clock and a reading lantern. Even while he was engaged in fighting he had works of literature read out to him. Then, during the periods when he wasn't fighting, he set out to translate into English the books which contained the wisdom he wanted his people to inherit. By producing such translations he became the "father of English prose".

Among the books Alfred translated were Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Soliloquies of Saint Augustine of Hippo, Universal History of Orosius and The Consolation of Philosophy of Boethius, the most popular philosophical handbook of the Middle Ages. He added several glosses to the work including the famous and oft-quoted sentence, "My will was to live worthily as long as I lived, and after my life to leave to them that should come after, my memory in good works." The book has come down to us in two manuscripts only. In one of these the writing is prose, in the other alliterating verse. The authorship of the latter has been much disputed; but likely they also are by Alfred. In fact, he writes in the prelude that he first created a prose work and then used it as the basis for his poem, the Lays of Boethius, his crowning literary achievement. He spent a great deal of time working on these books, which he tells us he gradually wrote through the many stressful times of his reign to refresh his mind. Of the authenticity of the work as a whole there has never been any doubt.

Beside these works of Alfred's, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was almost certainly started by him. It is a history of the English people in their own tongue compiled by monks and continued for more than two centuries after his death. No other nation in western Europe possesses any comparable record. A prose version of the first 50 Psalms has been attributed to him; and the attribution, though not proved, is perfectly possible. Additionally, Alfred appears as a character in The Owl and the Nightingale, where his wisdom and skill with proverbs is attested. Additionally, The Proverbs of Alfred, which exists for us in a thirteenth century manuscript, contains sayings that very likely have their origins partly with the king.

Family

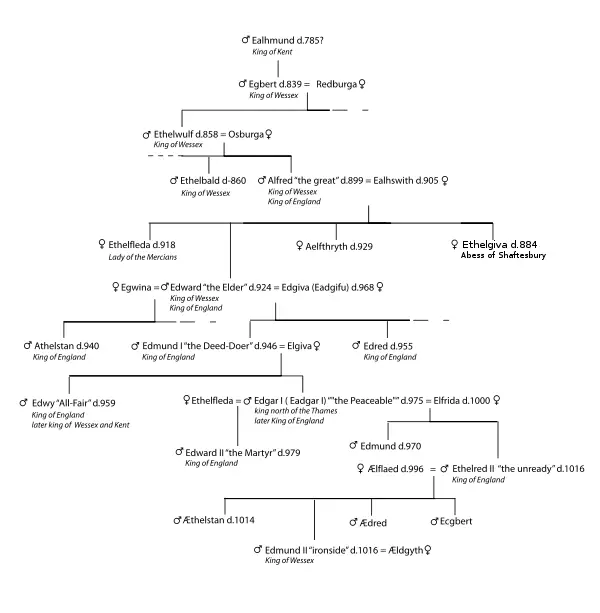

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of Aethelred Mucill, who is called Ealdorman of the Gaini, the people from the Gainsborough region of Lincolnshire. She appears to have been the maternal granddaughter of a King of Mercia. They had five or six children together, including Edward the Elder, who succeeded his father as King of Wessex; Ethelfleda, who would become Queen of Mercia in her own right, and Aelfthryth (alias Elfrida) who married Baldwin II, Count of Flanders.

Every monarch of England and subsequently every monarch of Great Britain and the United Kingdom, down to and including Queen Elizabeth II (and her own descendants) is directly descended from Alfred with the exception of Canute, William the Conqueror (who married Alfred's great-granddaughter Matilda), and his adversary Harold II.

Death and Legacy

Alfred died on October 26, 899. The actual year is not certain, but it was not necessarily 901 as stated in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. How he died is unknown. He had suffered for many years from a painful illness. He was originally buried temporarily in the Old Minster in Winchester, then moved to the New Minster (perhaps built especially to receive his body). When the New Minster moved to Hyde, a little north of the city, in 1110, the monks transferred to Hyde Abbey along with Alfred's body. His grave was apparently excavated during the building of a new prison in 1788 and the bones scattered. However, bones found on a similar site in the 1860s were also declared to be Alfred's and later buried in Hyde churchyard. Extensive excavations in 1999, revealed his grave-cut but no bodily remains.[8]

Alfred's work has endured. He created a kingdom which all Englishmen felt was their home and a native literature to enshrine their culture and tradition. He left no bitterness to be avenged after his death. Having saved Wessex and with it the English nation, he made no attempt to conquer others. Unlike Charlemagne he did not massacre his prisoners nor extend his rule by terror. He defeated enemies. He did not make them. Instead he recovered and extended the Anglo-Saxon political culture, infusing it with the spirit of Christ, that was to form the basis for the liberal democracy that has been so prized within the modern world. He certainly fulfilled his ambition: "My will was to live worthily as long as I lived, and after my life to leave to them that should come after, my memory in good works."

Cultural References

Literature and drama

- Thomas Augustine Arne's Masque of Alfred (first public performance: 1745) is a masque about the king. It incorporates the song "Rule Britannia."

- G. K. Chesterton's poetical epic The Ballad of the White Horse depicts Alfred uniting the fragmented Kingdoms of Britain to chase the northern invaders away from the island. It depicts Alfred as a divinely oriented leader waging holy war, in a similar way to Shakespeare's Henry V.

- In C. Walter Hodges' juvenile novels The Namesake and The Marsh King Alfred is an important character.

- G. A. Henty wrote an historical novel The Dragon and the Raven, or The Days of King Alfred.

- Joan Wolf's historical novel The Edge of Light (1990) is about life and times of Alfred the Great.

- The historical fantasy author Guy Gavriel Kay features Alfred in his novel The Last Light of the Sun (2004) thinly disguised under the name King Aeldred.

- Bernard Cornwell's series of books The Saxon Stories (2004~, currently consisting of The Last Kingdom, The Pale Horseman and The Lords of the North) depicts Alfred's life and his struggle against the Vikings from the perspective of a Saxon raised by Danes.

- A new biography of Alfred the Great by Justin Pollard was published by John Murray in 2005.

- Alfred Duggan wrote an historical novel biography of Alfred, entitled "The King of Athelny." It is a mixture of uncontested facts, as well as some stories of less certain authenticity, such as the burning of the cakes.

Film

- Alfred was played by David Hemmings in the 1969 film Alfred the Great, co-starring Michael York as Guthrum. [1].

- In 2006 a film, "The Saxon Chronicles," a biopic on Alfred the Great, was produced by director Jeshua De Horta [2].

Educational establishments

- The University of Winchester was named 'King Alfred's College, Winchester' between 1840 and 2004, whereupon it was re-named 'University College Winchester'.

- Alfred University, as well as Alfred State College located in Alfred, NY, are both named after the king.

- In honor of Alfred, the University of Liverpool created a King Alfred Chair of English Literature.

- University College, Oxford is erroneously said to have been founded by King Alfred.

- King Alfred's Community and Sports College, a secondary school in Wantage, Oxfordshire. The Birthplace of Alfred

- King's Lodge School, in Chippenham, Wiltshire is so named because King Alfred's hunting lodge is reputed to have stood on or near the site of the school.

See also

- British military history

- Kingdom of England

- Lays of Boethius

Notes

- ↑ Jacob Abbott. History of King Alfred of England. (NY: Harper & Brothers, [1877]; Boston, MA: Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.)

- ↑ Patrick Wormald, "Alfred (848/9–899)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- ↑ Arthur Bryant. The Story of England: Makers of the Realm. (London: Collins, 1953) ISBN 1842324691

- ↑ Bryant

- ↑ Sir Winston Churchill. The Island Race. (Corgi, London, 1964, II), 219.

- ↑ F. N. Lee, King Alfred the Great and our Common Law.fnlee.org. (Department of Church History, Queensland Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Brisbane, Australia, August 2000). Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ↑ Lee, F.N.; PDF file. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ↑ Aidan Dodson. The Royal Tombs of Great Britain. (London: G. Duckworth, 2004. ASIN B000K762SW)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Abbott, Jacob. History of King Alfred of England. NY: Harper & Brothers, [1877]; Boston, MA: Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. ISBN 9780543904249

- Bryant, Arthur. The Story of England: Makers of the Realm. London: Collins, 1953) ISBN 1842324691

- Campbell, J., Eric John and Patrick Wormald, (eds). The Anglo-Saxons. NY: Penguin, 1982. ISBN 9780140143959

- Churchill, Sir Winston. The Island Race. Corgi, London: 1964, Vol. II.

- Dodson, Aidan. The Royal Tombs of Great Britain. London: G. Duckworth, 2004. ASIN B000K762SW

- Palgrave, Sir Francis. History of the Anglo-Saxons. London: John Murray, [1837]; NY: Dorset Press, 1989. ISBN 9780880293372

- Pollard, Justin. Alfred the Great: the man who made England. London: John Murray, 2005. ISBN 0719566657

- Smyth, Alfred P. The Medieval Life of King Alfred the Great: A Translation and Commentary on the Text Attributed to Asser. NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 0333699173

- Wormald, Patrick, "Alfred (848/9–899)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004.

External links

All links retrieved July 20, 2023.

- Alfred the Great Ron Schuler's Parlour Tricks.

- King Alfred the Great David Nash Ford's Royal Berkshire History.

| House of Wessex Born: 849; Died: 26 October 899 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Ethelred |

King of Wessex 871–899 |

Succeeded by: Edward the Elder |

| Preceded by: Egbert (not proclaimed) (829-830) |

King of England 878–899 |

Succeeded by: Edward the Elder |

| Preceded by: Ethelred |

Bretwalda 871–899 |

Succeeded by: None |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.