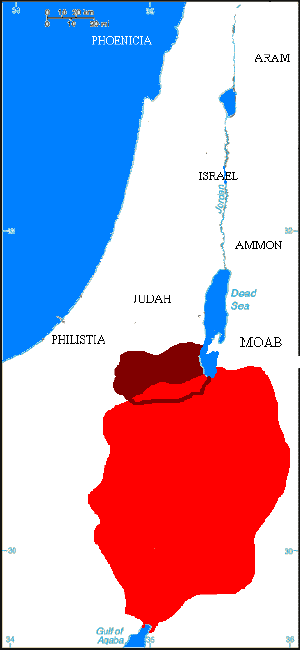

The Amalekites were a biblical people and enemy of the Israelites. They were reportedly wiped out almost entirely as the result of Israelite victories against them in wars beginning shortly after the Exodus and continuing into the period of the early Israelite monarchy. Amalekite settlements are reported in the biblical record as late as the reign of King Hezekiah in the eighth century B.C.E., and the Book of Esther portrays its later villain, Haman, as a descendant of an Amalekite prince.

The Amalekites are unknown historically and archaeologically outside of the Bible except for traditions which themselves apparently rely on biblical accounts. In the Bible, the Amalekites are said to have descended from a common ancestor named Amalek, a grandson of Esau. In this sense they may be considered as one of the Edomite tribes. Jewish tradition sees the Amalekites as an implacable enemy of both God and Israel.

Biblical account

Origins

The first reference to the Amalekites is found in Genesis 14, which describes a military campaign of Kedorlaomer, king of Elam, and his allies which took place in Abraham's day before the birth of Isaac. Kedorlaomer conquered territories of the Amalekites, the Horites of Seir, Amorites, and others.

On the other hand, Genesis 36:12 describes the birth of Amalek himself as Esau's grandson, born four generations after the events of Kedorlaomer's time. This account makes the Amalekites one of the Edomite tribes, descended from Esau's firstborn son, Eliphaz. Amalek's mother was named Timna, a Horite princess descended from Seir, for whom Edom's Mount Seir was named.

Israel's enemy

The Amalekites do not appear again until 400 years later, when Moses is leading the Israelites toward Canaan from Egypt. At Rephidim, the Amalekites suddenly appear and attack the Israelites, who are apparently trespassing on their territory. Moses commissions the young Joshua to act as general for the Israelites. Moses climbs a nearby hill to watch the battle, and a see-saw battle ensues, with the Amalekites prevailing whenever Moses lowers his arms and the Israelites prevailing whenever he raises them. Aaron and Hur help the aging Moses hold his arms high, and Joshua's forces eventually prove victorious.

God then pronounces the Amalekites' doom, commanding Moses: "Write this on a scroll as something to be remembered and make sure that Joshua hears it, because I will completely blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven." (Exodus 17:14) This event occurs near the beginning of the Exodus, before the incident of the Golden Calf, and we do not hear of the Amalekites again until nearly 40 years later. As the Israelites prepare to enter the Promised Land, Moses reminds them that the Amalekites are not to be forgiven:

Remember what the Amalekites did to you along the way when you came out of Egypt. When you were weary and worn out, they met you on your journey and cut off all who were lagging behind; they had no fear of God. When the Lord your God gives you rest from all the enemies around you in the land he is giving you to possess as an inheritance, you shall blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven. Do not forget! (Deuteronomy 25:17-19)

Later, the Israelites mass east of the Jordan to prepare their conquest of Canaan. There, the famous prophet Balaam is hired by the Moabite king Balak to curse Israel and ensure the Israelites' defeat, but Balaam, inspired by God, only blesses Israel instead. In the process, he gives the following oracle concerning the Amalekites: "Amalek was first among the nations, but he will come to ruin at last." (Numbers 24:20)

Against the Judges

The Amalekites are not mentioned in the Book of Joshua, as the Israelites march from victory to victory against the Canaanite tribes. In the Book of Judges, however, they make several appearances. Here they are described as an eastern tribe of the "hill country." They join forces with Eglon, king of Moab, to reconquer Jericho.[1] The result is that: "The Israelites were subject to Eglon king of Moab for eighteen years." (Judges 3:14)

Interestingly, the Song of Deborah (Judges 5:14) refers people in the territory of Ephraim, "whose roots were in Amalek," as joining Deborah's military campaign against the Canaanite king Jabin. On the other hand, the judge Gideon helps rid his territory of Amalekites, Midianites, "and other eastern peoples" who raided Israelite areas and spoiled their crops. (Judges 6)

Destroyed by Saul and David

It would be the kings Saul and ultimately David, however, who finally fulfilled—or nearly fulfilled—the doom pronounced earlier by Moses against the Amalekites. Saul "fought valiantly and defeated the Amalekites, delivering Israel from the hands of those who had plundered them." (1 Samuel 14:48) After this, God commands Saul to exterminate the Amalekites entirely:

I will punish the Amalekites for what they did to Israel when they waylaid them as they came up from Egypt. Now go, attack the Amalekites and totally destroy everything that belongs to them. Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys. (1 Samuel 15:2-3)

Saul warns the Kenites, who dwell among the Amalekites, to move away from them. He then "attacked the Amalekites all the way from Havilah to Shur, to the east of Egypt. He took Agag king of the Amalekites alive, and all his people he totally destroyed with the sword." (1 Samuel 15:7-8) According to the prophet Samuel, however, God was not satisfied with this. For sparing Agag and allowing Israel's soldiers to plunder some of the Amalekite cattle, God rejects Saul as king. Samuel himself finishes the slaughter of the Amalekites by "hewing Agag in pieces before the Lord." (1 Samuel 15:33)

The destruction of the Amalekites, however, is not as complete as it seems. The future king David encounters them later in Saul's reign when David is serving the Philistine King Achish, having been declared an outlaw by Saul. As a Philistine vassal, David conducts raids against the Amalekite towns, killing all their inhabitants but sharing the plunder with Achish. While David is on campaign with Achish, the Amalekites retaliate against him by raiding and burning his town of Ziklag and taking his property, including his wives, Ahinoam and Abigail.[2]

David meets a wounded Egyptian slave belonging to the Amalekites, who leads him to the Amalekite camp. David's forces attack the Amalekites and succeed in freeing the captives, including David's wives. He kills all of the Amalekites except for 400 young men who get away on camels. Back in Ziklag, David receives news of Saul's death from an Amalekite man who claims to have slain the king at Saul's own request while the king was in his death throes after the Battle of Gilboa. David immediately has the man executed. (2 Samuel 1) In 2 Samuel 8, Amalekites are listed among those people subdued by David and whose sacred articles he dedicated to God. It is further reported that David killed 18,000 Edomites in the Valley of Salt, although it is not specified if these included Amalekites.

No further mention is made of the Amalekites until the reign of King Hezekiah of Judah in the eighth century B.C.E. An Amalekite remnant is described as having "escaped" and are still living in the "hill country of Seir," where they are destroyed by 500 Simeonite families who have migrated to the area, "because there was pasture for their flocks." (1 Chronicles 4)

Rabbinical views

In Jewish tradition, the Amalekites came to represent the archetypal enemy of the Jews. For example, Haman, the murderous villain of the Book of Esther, is called the "Agagite," which is interpreted as being a descendant of the Amalekite king Agag. Of the 613 mitzvot (commandments) followed by Orthodox Jews, three refer to the Amalekites: to remember what the Amalekites did to the Jews, to remember what the Amalekites did to the Israelites in the wilderness, and to destroy the Amalekites utterly.

The first century Jewish historian Josephus preserves a tradition justifying the slaughter of Amalekite women and children by King Saul:

"He betook himself to slay the women and the children, and thought he did not act therein either barbarously or inhumanly; first, because they were enemies whom he thus treated, and, in the next place, because it was done by the command of God, whom it was dangerous not to obey" (Flavius Josephus, Antiquites Judicae, Book VI, Chapter 7).

Talmudic sages justified the treatment of the Amalekites on the ground of Amalekite treachery toward Israel. Not only did the Amalekites attack the Israelites, one opinion states, they first deceived them into believing they merely wanted to negotiate peacefully. Moreover, they attacked from the rear in a cowardly fashion and mutilated the bodies of those Israelites they succeeded in killing. (Pesik. R. 12, Mek. BeshallaḦ)

The great medieval sage Maimonides, however, explained that the commandment to destroy the nation of Amalek is by no means absolute. Indeed, according to the Deuteronomic precepts, before fighting, it is required that the Israelites peacefully request of them to accept the Noachide laws and pay a tax to the Jewish kingdom. Only if they refuse is the commandment applicable.

The hasidic teacher known as the Baal Shem Tov used the term "Amalekite" to represent the rejection of God, or atheism. The term has been used metaphorically to refer to enemies of Judaism throughout history, including the Nazis, and controversially, by some to refer to those among the Arabs who attempt to destroy Israel today. Samuel's words to Agag: "As your sword bereaved women, so will your mother be bereaved among women" (Samuel 1:15:33) were repeated by Israeli president Itzhak Ben-Zvi in his letter turning down Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann's petition for mercy before his execution. [3]

Critical views

The origins and identity of the Amalekites remain a subject of discussion, and the ethics of their treatment by the Israelites are a topic of contentious debate.

No archaeological evidence of the Amalekites exists that can be distinguished from their Edomite and other semitic counterparts. It is thus impossible to identify them historically outside of the biblical record, which is written by their mortal enemies, the very people who claim to have exterminated them at God's command.

The Bible itself gives contradictory accounts of their origins. Genesis 14 describes them as present already in Abraham's time, while the prophet Balaam calls them as "the first of the nations." Genesis 36 contradicts this by portraying them as an Edomite clan descended from Esau's son Eliphaz, by his concubine Tinma. That they operated in the territory of the Edomites and also in the hill country east of the Jordan River seems clear, although their reported presence at Rephidim puts them farther south in the Sinai peninsula. This is certainly plausible if they, like other semitic tribes, were nomadic. The report of Amalekites existing in Abraham's time, meanwhile, is seen as evidence that the Book of Genesis consists of multiple sources which do not always agree with each other, for they could not have been so ancient if they were descendant from Esau's grandson.

Being a tribe of the Edomites would make the Amalekites immune from destruction by the Israelites, since God commanded the Israelites to treat the Edomites as brothers (Deuteronomy 23:7). The biblical writers may have used the unprovoked attack by the Amalekites against the Israelites during the Exodus to supersede this injunction, making the Amalekites a special case—reprobate Edomites not to be treated as brothers, but singled out by God Himself for extermination.

The commandment of God to destroy the Amalekites seems to be a clear case of biblically-endorsed genocide that has troubled commentators from time in memoriam. The fact that the Amalekites had attacked the Israelites during the Exodus seems inadequate grounds to justify such a drastic policy. Supporters of the doctrine of biblical inerrancy argue that since God is good and the Bible says that God commanded the extermination of the Amalekites, then actions toward that end—even the killing of women and children—must be good in this case. Indeed, the slaughter of the Amalekites was such a moral imperative that Saul's failure to fulfill the order completely is said to have disqualified him from the kingship. Arguing against this, biblical critics claim that histories such as those in the Bible are written "by the winners," who are free to make whatever claims they wish to about God's supposed will, since they victims cannot answer them. Such critics argue that by any objective standard, the actions of military leaders such as Saul and David toward the Amalekites must be judged as war crimes of the first order.

Footnotes

- ↑ Jericho here is referred to as the City of Palms. The passage seems to contradict the Book of Joshua and later claims that the city remained in ruins.

- ↑ David is fortunate that the Amalekites do not kill all of the town's inhabitants, as David and Saul reportedly both did to Amalekite towns.

- ↑ Yoseph Carmel. Itzchak Ben Zvi from his Diary in the President's office. (Mesada: Ramat Gan, 1967), 179.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Evans, Mary. The Message of Samuel: Personalities, Potential, Politics, and Power. InterVarsity Press (2004). ISBN 0830824294

- Feldman, Louis H. REMEMBER AMALEK!—Vengeance, Zealotry, and Group Destruction in the Bible. Hebrew Union College Press, 2004. ISBN 9780878204557

- Horowitz, Elliott. Reckless Rites: Purim and the Legacy of Jewish Violence. Princeton University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780691124919

- Sagi, Avi. "The Punishment of Amalek in Jewish Tradition: Coping with the Moral Problem." Harvard Theological Review 87(3) (1994): 323-346.

External links

All links retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Amalek, Based on the teachings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. www.chabad.org.

- Amalek. www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- Amalec. www.newadvent.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.