Archetype

The archetype, a concept developed by Carl Jung, refers to an idealized or prototypical model of a person, object, or concept, similar to Plato's ideas. According to Jung, archetypes reside in the level of our unconscious mind that is common to all human beings, known as the collective unconscious. These archetypes are not readily available to our conscious mind, but manifest themselves in our dreams and other mystical experiences. While commonalities in the stories and characters found in all cultures support the existence and universality of archetypes, and they have proven useful in the study of mythology, literature, and religions of the world, their exact nature and origin remain to be determined.

Definition

The archetype is a concept first developed in psychology by Carl Jung. For Jung, the "archetype is an explanatory paraphrase of the Platonic eidos" (Jung et. al. 1979). The concept of archetype was already in use at the time of Saint Augustine, who, in De deversis quaestionibus, speaks of "ideas...which are not yet formed...which are contained in the divine intelligence." Jung distinguished his concept and use of the term from that of philosophical idealism as being more empirical and less metaphysical, though most of his "empirical" data were dreams.

In Jung's theory, archetypes are innate prototypes for ideas, which may subsequently become involved in the interpretation of observed phenomena. A group of memories and interpretations closely associated with an archetype is called a complex, and may be named for its central archetype (e.g. "mother complex"). Jung often seemed to view the archetypes as sort of psychological organs, directly analogous to our physical, bodily organs: both being morphological givens for the species; both arising at least partially through evolutionary processes. Jung hypothesized that all of mythology could be taken as a type of projection of the collective unconscious.

The archetypes reside in the unconscious, which Jung described as made up of two layers. The top layer contains material that has been made unconscious artificially; that is, it is made up of elements of one's personal experiences, the personal unconscious. Underneath this layer, however, is the collective unconscious: an absolute unconscious that has nothing to do with personal experiences. Jung described this bottom layer as "a psychic activity which goes on independently of the conscious mind and is not dependent even on the upper layers of the unconscious—untouched, and perhaps untouchable—by personal experience" (Campbell, 1971). It is within this layer that archetypes reside.

Jung's life work was to make sense of the unconscious and its habit of revealing itself in symbolic form through manifestations of the archetypes of the collective unconscious. He believed that it was only possible to live a full life when in harmony with these archetypal symbols; "wisdom is a return to them"(Jung, Adler, and Hull, 1970, p. 794). Jung postulated that the symbols and archetypes of an individual's collective unconscious can be primarily discovered by that person's dreams, revealing important keys to the individual's growth and development. Through the understanding of how an individual patient's unconscious integrates with the collective unconscious, that patient can be helped towards achieving a state of individuation, or wholeness of self.

Jungian archetypes

Jung uncovered the various archetypes through careful recording of his own dreams, fantasies, and visions, as well as those of his patients. He found that his experiences formed themselves into persons, such as a wise old man who, over the course of many dreams, became a kind of spiritual guru, a little girl who became his main channel of communication with his unconscious, and a brown dwarf who seemed to represent a warning about certain dangerous tendencies. Jung found that archetypes have both good and bad manifestations, reflecting his principle of opposites in the psyche.

The key archetypes that Jung felt were especially important include: the persona, the shadow, the anima/animus, the mother, the father, the wise old man, and the self. Others include the trickster, the God image, the Syzygy (Divine Couple), the child, the hero and a variety of archetypal symbols.

The Self

The self, according to Jung, is the most important archetype. It is called the "midpoint of the personality," a center between consciousness and the unconscious, the ultimate unity of the personality. It signifies the harmony and balance between the various opposing qualities that make up the psyche. The symbols of the self can be anything that the ego takes to be a greater totality than itself. Thus many symbols fall short of expressing the self in its fullest development.

Symbols of the self are often manifested in geometrical forms such as circles, a cross, (mandalas), or by the quaternity (a figure with four parts). Prominent human figures which represent the self are the Buddha or Christ.

The Persona

The persona comes from a Latin word for mask, and represents the mask we wear to make a particular impression on others. It may reveal or conceal our real nature. It is an artificial personality that compromises a person's real individuality and society's expectations—usually society's demands take precedence. It is made up of such things as professional titles, roles, habits of social behavior, etc. It serves to both guarantee social order and to protect the individual's private life. A person may also have more than one persona.

The persona is a compromise between what we wish to be and what the surrounding world will allow us to be; it is the manifestation of interactional demands. It may be our attempt to appear as society expects us, or it may be a false mask that we use to trick and manipulate others. The persona can be mistaken, even by ourselves, for our true nature. Thus, there is a danger in identifying totally with the persona, becoming nothing but the role one plays.

Although the persona begins as an archetype, part of the collective unconscious of all human beings, in some cases, individuals may make so much effort to perfect it that their persona is no longer within this common realm.

The Shadow

The shadow is a part of the unconscious mind, which is mysterious and often disagreeable to the conscious mind, but which is also relatively close to the conscious mind. It may be in part one's original self, which is superseded during early childhood by the conscious mind; afterwards it comes to contain thoughts that are repressed by the conscious mind. The shadow is instinctive and irrational, but is not necessarily evil even when it might appear to be so. It can be both ruthless in conflict and empathetic in friendship. It is important for the understanding of one's own more inexplicable actions and attitudes (and of others' reactions), and for learning how to cope with the more problematic or troubling aspects of one's personality.

The shadow is said to be made up of all the reprehensible characteristics that each of us wish to deny, including animal tendencies that Jung claims we have inherited from our pre-human ancestors. Thus, the shadow contains more of instinctive nature than any other archetype does. It is the source of all that is best and worst in human beings, especially in our relations with others of the same sex.

When individuals recognize and integrate their shadows, they progress further towards self-realization. On the other hand, the more unaware of the shadow we are, the blacker and denser it is, and the more dissociated it is from conscious life, the more it will display a compensatory demonic dynamism. It is often projected outwards on individuals or groups, who are then thought to embody all the immature, evil, or repressed elements of the individual's own psyche.

The shadow may appear in dreams and visions in various forms, often as a feared or despised person or being, and may act either as an adversary or as a friend. It typically has the same apparent gender as one's persona. The shadow's appearance and role depend greatly on individual idiosyncrasies because the shadow develops in the individual's mind, rather than simply being inherited in the collective unconscious.

Interactions with the shadow in dreams may shed light on one's state of mind. A disagreement with the shadow may indicate that one is coping with conflicting desires or intentions. Friendship with a despised shadow may mean that one has an unacknowledged resemblance to whatever one hates about that character.

According to Jung, the shadow sometimes takes over a person's actions, especially when the conscious mind is shocked, confused, or paralyzed by indecision.

The Anima/animus

The anima/animus personifies the soul, or inner attitude. Following a person's coming to terms with their shadow, they are then confronted with the problem of the anima/animus. It is usually a persona and often takes on the characteristics of the opposite sex. The anima is said to represent the feminine in men and the animus is the comparable counterpart in the female psyche. The anima may be personified as a young girl, very spontaneous and intuitive, as a witch, or as the earth mother. It is likely to be associated with deep emotionality and the force of life itself. Jung viewed the anima/animus process as being one of the sources of creative ability.

Jung regarded the gender roles we play as men and women to be societally, not biologically, determined. He saw human beings as essentially bisexual, in that we all have both masculine and feminine aspects to our nature. Thus, by fulfilling society's expectations, we achieve only part of our actual potential as human beings. The anima/animus archetype represents our "other half," and in order to feel whole we need to acknowledge and relate to it as part of our own personality.

In a film interview, Jung was not clear if the anima/animus archetype was totally unconscious, calling it "a little bit conscious" and unconscious. In the interview, he gave an example of a man who falls head over heels in love, then later in life regrets his blind choice as he finds that he has married his own anima–the unconscious idea of the feminine in his mind, rather than the woman herself.

Anima

The anima, according to Jung, is the feminine side of a male's unconscious mind. It can be identified as all the unconscious feminine psychological qualities that a male possesses. The anima is usually based on a man's mother, but may also incorporate aspects of sisters, aunts, and teachers.

Jung also believed that every woman has an analogous animus within her psyche, this being a set of unconscious masculine attributes and potentials. He viewed the animus as being more complex than the anima, as women have a host of animus images while men have one dominant anima image.

The anima is one of the most significant autonomous complexes. It manifests itself by appearing as figures in dreams, as well as by influencing a man's interactions with women and his attitudes toward them. Jung said that confronting one's shadow is an "apprentice-piece," while confronting one's anima is the masterpiece. He also had a four-fold theory on the anima's typical development, beginning with its projection onto the mother in infancy, continuing through its projection on prospective sexual partners and the development of lasting relationships, and concluding with a phase he termed Sophia, a Gnostic reference. It is worth noting that Jung applied similar four-fold structures in many of his theories.

Animus

According to Jung, the animus is the masculine side of a woman's personal unconscious. It can be identified as all the unconscious masculine psychological qualities that a woman possesses.

Animus is also considered to be that natural and primitive part of the mind's activity and processes remaining after dispensing with the persona, or "mask" displayed in interactions with others, which has been shaped by socialization. The animus may be personified as a Wise Old Man, a sorcerer, or a number of males. It tends to be logical and often argumentative.

Syzygy

Together, the anima and animus form a divine pair known as the syzygy. The syzygy consists of three elements:

- the femininity pertaining to the man (anima) and the masculinity pertaining to the woman (animus);

- the actual experience man has of woman and vice versa;

- the masculine and feminine archetypal image.

In ancient Greek mythology we find an example of the divine pair in the gods Hermes and Aphrodite. Jung also observed that the divine pair occupies the highest place in Christianity as Christ and his bride, the Church. In Hinduism almost all the major forms of God are Divine pairs.

Great Mother

Great Mother is the personification of the feminine and represents the fertile womb out of which all life comes and the darkness of the grave to which it returns. Its fundamental attribute is the capacity to nourish. As infants, we cannot survive without a nurturer. If we do not have a nurturing mother, we seek one and project this archetype upon that person. If no real person is available, we personify the archetype. We may also spend our time seeking comfort through a less personal symbol, such as the church, the "motherland," or a life on the ocean.

If the great mother nourishes us, she is good. However, if she threatens to devour us, she is bad. In psychological terms, the great mother corresponds to the unconscious, which can nourish and support the ego or can swallow it up in psychosis or suicide. The positive, creative aspects of the great mother are represented by breast and womb. Mother is the source of life and nurture and the images are nearly inexhaustible: anything hollow, concave or containing, such as bodies of water, the earth itself, caves, dwellings, and vessels of all kinds.

Father

As the great mother pertains to nature, matter and earth, the great father archetype pertains to the realm of light and spirit. It is the personification of the masculine principle of consciousness symbolized by the upper solar region of heaven. From this region comes the wind, which has always been the symbol of spirit as opposed to matter. Sun and rain likewise represent the masculine principle as fertilizing forces, which impregnate the receptive earth. Images of piercing and penetration such as phallus, knife, spear, arrow and ray all pertain to the spiritual father. All imagery involving flying, light, or illumination pertains to the masculine principle, as opposed to the dark earthiness of the great mother.

The positive aspect of the spiritual father principle conveys law, order, discipline, rationality, understanding, and inspiration. Its negative aspect is that it may lead to alienation from concrete, physical reality.

Wise Old Man

The image of the wise old man as judge, priest, doctor, or elder is a human personification of the father archetype. He is also known as the "Senex" and is an archetype of meaning or spirit. It often appears as grandfather, sage, magician, king, doctor, priest, professor, or any other authority figure. It represents insight, wisdom, cleverness, willingness to help, and moral qualities. His appearance serves to warn of dangers and provide protective gifts. As with the other archetypes, the wise old man also possesses both good and bad aspects.

The wise old man is often in some way "foreign," that is from a different culture, nation, or time from those he advises.

The Trickster

Jung describes the trickster figure as a faithful representation of the absolutely undifferentiated human psyche that has hardly left the animal level. The trickster is represented in normal man by countertendencies in the unconscious that appear whenever a man feels himself at the mercy of apparently malicious accidents.

In mythology, the trickster's role is often to hamper the hero's progress and generally cause trouble. The half-god "Loki" is a typical example of a trickster who constantly plays tricks on the Norse gods. In folklore, the trickster is incarnated as a clever, mischievous man or creature, who tries to survive the dangers and challenges of the world using trickery and deceit as a defense. With the help of his wits and cleverness, instead of fighting, he evades or fools monsters, villains, and dangers with unorthodox methods.

The trickster breaks the rules of the gods or nature, sometimes maliciously, but usually with ultimately positive effects. Often, the rule breaking takes the form of tricks or thievery. Tricksters can be cunning or foolish, or both; they are often very funny even when considered sacred or performing important cultural tasks.

For a modern humanist, study of the trickster archetypes and their effects on society and its evolution, see Trickster Makes The World: Mischief, Myth, and Art by Lewis Hyde.

Archetypal symbols

Here are a few examples of archetypal symbols:

- The mandala, a circle, often squared, can also symbolize the wholeness of the Self or the yearning for such wholeness.

- Light/darkness (representing the conscious and the unconscious), water or wetness/dryness or the desert, heaven/hell.

- Birds often symbolize the spirit (e.g., the Holy Spirit as a dove), but may symbolize many other things, including fear and destruction, courage, or wisdom. For many Native Americans, the eagle is a particularly sacred symbol.

- Caves can symbolize the unconscious, as can bodies of water, the forest, night, and the moon. These tend to be feminine symbols, just as anything that encloses or nourishes, depending on the context, can be a feminine symbol.

- In addition to light, the sky, the sun, or the eyes, can symbolize consciousness.

Expressions of Archetypes

Mythology

Jung investigated mythologies and mystical traditions from around the world in his research on archetypes. Some examples illustrating several archetypes are as follows.

Wise Old Man

- Merlin from the Matter of Britain and the legends of King Arthur

- Odin principal deity of Norse mythology

- Tiresias from the Odyssey, Oedipus Rex, and other Greek myths

- Utnapishtim from the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Trickster

- Agu Tonpa in Tibetan folklore

- Amaguq in Inuit mythology

- Ananse in Ashanti mythology

- Awakkule and Mannegishi in Crow mythology

- Azeban in Abenaki mythology

- Bamapana in Australian Aboriginal mythology

- Eris, Prometheus, Hephaestos, Hermes Trismegistus, Odysseus in Greek mythology

- Brer Rabbit in American folklore

- Cin-an-ev in Ute mythology

- Fairy and Puck in Celtic mythology

- Iktomi in Lakota mythology

- Iwa and Kaulu in Polynesian mythology

- Kantjil in Indonesian folklore

- Kappa, Maui in Hawaiian mythology

- Kitsune and Susanoo in Japanese mythology

- Kokopelli in Hopi and Zuni mythology

- Kwaku Ananse in Akan mythology

- Loki in Norse mythology

- Nanabozho in Chippewa mythology

- Nanabush in Ojibwe mythology

- Nankil'slas, Raven spirit in Haida mythology

- Ndauthina in Fijian mythology

- Nezha, Sun Wukong (the Monkey King) in Chinese mythology

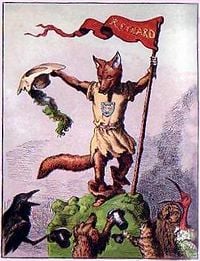

- Reynard the Fox in French folklore

- Saci-Pererê in Brazilian folklore

- San Martin Txiki in Basque mythology

- Tezcatlipoca in Aztec mythology

- Till Eulenspiegel in German folklore

- Tonenili in Navajo mythology

Literature

Archetypes are often discussed in literature. The epic poem Beowulf describes one of the most famous Anglo-Saxon hero archetypes. William Shakespeare is known for popularizing many archetypal characters. Although he based many of his characters on existing archetypes from fables and myths, Shakespeare's characters stand out as original by their contrast against a complex, social literary landscape.

Popular culture

As with other psychologies which have infiltrated mass thought, archetypes are now incorporated into popular culture, such as movies, novels, video games, comics, art, and television programs.

The Star Wars films include a number of archetypes revealed as the story unfolds: Luke Skywalker exemplifies the hero. Initially ignorant of the truth of the collective unconscious (the Force), he begins by rescuing the maiden (Princess Leia), who later develops into the anima (Luke's twin sister). He fights the shadow (Darth Vader), guided by the wise old man (Obi Wan Kenobi, later Yoda, and finally Anakin Skywalker when Darth Vader dies) (Boeree 2006).

The following are a few more examples of the wise old man and trickster archetypes in popular culture.

Wise Old Man

- Abbot Mortimer from Brian Jacques's novel Redwall

- Albus Dumbledore from J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series

- Ancient One from Doctor Strange

- Auron from Final Fantasy X

- Gandalf from J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings series

- Allanon from Terry Brooks' Shannara series

- Brom from Christopher Paolini's Inheritance Trilogy

- Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid

- Morpheus from The Matrix

- Oogruk from Gary Paulsen's novel Dogsong

- Press Tilton from the Pendragon series

- Professor X from the X-Men

- Rafiki from The Lion King

- Thufir Hawat from Dune

Trickster

- Arsene Lupin, the gentleman thief from Maurice Leblanc's novel series of the same name

- Bugs Bunny

- Bart Simpson from The Simpsons

- Captain Jack Sparrow from Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl

- Jerry Mouse from Tom & Jerry

- Matrim Cauthon from the Wheel of Time fantasy book series

- Mr. Mxyzptlk, a tormentor of Superman

- Plastic Man, comic artist Jack Cole's shape shifting superhero

- Q from Star Trek

- The Tramp, Charlie Chaplin's famous silent film character

- The Trickster, a super villain in the DC Universe who has been both an ally and an enemy of The Flash

- The Riddler, DC Comics super villain, an enemy of Batman

Archetypes in Personal Development

In her book, Sacred Contracts, Carolyn Myss described the archetype as an organizing principle and pattern of intelligence that shapes the energy within us, thereby shaping our lives. Her pioneering work with Norman Shealy, in the field of energy medicine and human consciousness, has helped define how stress and emotion contribute to the formation of disease. Drawing from the archetypal research of Jung, as well as a study of mythology, she sees the archetype as an insight into a person's psyche that helps an individual to better understand their life situation.

Myss believes that awareness of how an archetype is dominating one's life can help a person break the pattern and become "his/her own master." The individual is encouraged to embody what is positive in the archetype, while consciously choosing what to let go of. To do this, it is necessary to step back from one's life to see the whole picture, and see which archetypes are dominant. According to Myss, this gives clues to one's life mission and relationships.

Evaluation

Although Jung's research found commonalities in the archetypes revealed in mythologies, religions, and other cultural expressions throughout the world, this is not conclusive proof of their universal or innate character. Jung himself noted that there is not a fixed number of distinct archetypes, and that they do not follow the usual logic of the physical world but rather appear to overlap and merge into each other. Thus, the concept of archetypes, along with the collective unconscious itself, can be criticized as essentially theoretical, or metaphysical, and not substantiated by empirical data.

On the other hand, archetypes have proved useful in the analysis of myths, fairy tales, literature, artistic symbolism, and religious expression. It does appear that there is a limited number of stories and characters in human experience, indicating connections among human beings throughout history and the world. Thus, even if Jung did not have the correct explanation of the exact nature of these connections, there is value and some level of validity to his notion of archetypes.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boeree, C. George. 1997, 2006. Carl Jung Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- Campbell, Joseph. 1971. The Portable Jung. Translated by R.F.C. Hull. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140150706.

- Hyde, Lewis. 1998. Trickster Makes this World: Mischief, Myth, and Art. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374958033

- Johnson, Robert A. 1993. Owning Your Own Shadow: Understanding the Dark Side of the Psyche. Harper San Francisco. ISBN 0062507540

- Johnson, Robert A. 1989. Inner Work: Using Dreams and Creative Imagination for Personal Growth and Integration. Harper San Francisco. ISBN 0062504312.

- Jung, C. G., Adler, Gerhard, and Hull, R.F.C. 1970. The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche (Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 8) Bollingen. ISBN 0691097747

- Jung, C. G., Adler, Gerhard, and Hull, R.F.C. 1979. Collected Works of C.G. Jung Volume 9 Part 2. Bollingen. ISBN 069101826X.

- Jung, C. G., & Campbell, J. 1976. The Portable Jung, a compilation. New York, NY: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140150706.

- Jung, C. G. and McGuire, William. 1969. Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9, Pt. 1). Bollingen. ISBN 0691097615

- Jung, C. G., Wagner, S., Wagner, G., & Van der Post, L. 1990. The World Within C.G. Jung in his own words [videorecording]. New York, NY: Kino International: Dist. by Insight Media.

- Myss, Carolyn. 2003. Sacred Contracts: Awakening Your Divine Potential. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0609810111.

External links

All links retrieved August 12, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Archetype history

- Shadow_(psychology) history

- Anima_(Jung) history

- Animus history

- Wise_Old_Man history

- Trickster history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.png/200px-Carl_Jung_(1912).png)