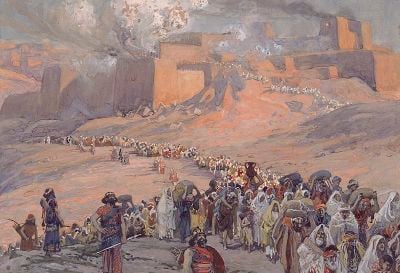

The Babylonian exile (or Babylonian captivity) is the name generally given to the deportation and exile of the Jews of the ancient Kingdom of Judah to Babylon by Nebuchadrezzar II. The Babylonian exile is distinguished from the earlier exile of citizens of the northern Kingdom of Israel to Assyria around 722 B.C.E. The exile in Babylon—which directly affected mainly those of the upper class of society—occurred in three waves from 597 to 581 B.C.E. as a result of Judean rebellions against Babylonian rule. The Bible portrays the internal cause of the captivity as the sins of Judah in failing to rid herself of idolatry and refusing to heed prophetic warnings not to rebel against Babylon.

While the Jews in Babylon did not suffer greatly in the physical sense, the siege and later sack of Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E., including the destruction of its sacred Temple, left many of the exiles deeply repentant and determined to keep their faith pure. After Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylon, he allowed the exiles to return in 537 B.C.E. They came to Jerusalem with a tradition refined by the rise of the scribal profession, deeply committed to ethnic purity centering on the rebuilt Temple, and yet enriched by universalistic monotheistic values.

The Babylonian exile represents both one of Judaism's darkest hours and also the beginning of its history as an enduring universal religion that gave birth to the later monotheistic traditions of Christianity and Islam.

Deportations

The first deportation from Judah occurred in 597 B.C.E., as a result of the conquest of Jerusalem by Nebuchadrezzar II. The purpose of this action was to punish King Josiah's son Jehoiakim, once Babylon's vassal, for allying with Egypt and rebelling against Babylonian dominance (2 Kings 24:1). Against Babylon's superior forces, Jehoiakim retained no territory except Jerusalem when he died of natural causes. His son Jehoiachin, also called Jeconiah, continued to resist until he was forced to surrender after a reign of only three months. Nebuchadnezzar ordered him and the elite citizens of Judah deported, together with the most valuable treasures of the Temple and the palace (2 Kings 24 1-16). Among the captives was the prophet Ezekiel, though not Jeremiah, who remained in Jerusalem, where he counseled cooperation with Babylon.

Jeremiah advised those taken to Babylon to settle there peacefully, and not hope to return for at least 70 years. They were even to pray for Nebuchadrezzar, for he was God's instrument to punish Judah for her sins. He strongly urged those in Jerusalem to be patient and resist the urge to rebel. This advice was opposed forcefully by the prophet Hananaiah, who urged the new king, Zedekiah, to have faith that God would deliver Judah from the hand of its oppressor (Jer. 28).

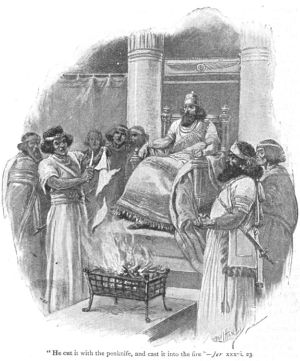

Jeremiah's advice would ultimately go unheeded. Zedekiah, who, like his predecessor Jehoiakim, had taken the oath as a vassal of Nebuchadrezzar (Ezek. 17:13), rebelled. Nebuchadrezzar, reaching the end of his patience, began the siege of Jerusalem in January 587. He was soon forced to abandon the siege in order to face Zedekiah's Egyptian allies. After defeating them in battle, however, the Babylonian forces renewed their assault on Jerusalem, finally breaching its walls in July 586. Zedekiah and his court attempted to flee, but were captured. As punishment, he was forced to witness the death of his sons and then he was blinded. After this, the king was taken in chains to Babylon.

In August of the same year, while they watched with spiritual eyes in troubled visions from Babylon, Nebuchadrezzar’s captain, Nebuzaradan, supervised the destruction and burning of the Temple of Jerusalem, the royal palace, and virtually the entire city. Hundreds of the surviving inhabitants were deported to Babylon, but another 70-80 leading citizens, including the high priest Seraiah, were put to death (2 Kings 25, Jer. 34). A notable exception was the prophet Jeremiah, who was rightly viewed by the Babylonians as a vocal opponent of the rebellion.

Nebuchadrezzar appointed the collaborator Gedaliah to govern what remained of Judah from Mizpah. After seven months, however, Gedaliah was assassinated, and another rebellion broke out. Many Judeans escaped to Egypt during this time. Among them was Jeremiah, who apparently went very reluctantly after prophesying against such a course (Jer. 41-43). In retribution against the rebels, a third deportation was ordered by Nebuchadnezzar around 582-581 B.C.E.

Numbers and conditions

According to the Book of Jeremiah (52:28-30), 3,023 Jews were deported in the first wave, 832 in the second, and 745 in the third, making 4,600 in all. However, it is likely that only the men were counted. Including women and children it is estimated that 14,000 to 18,000 people would be the full number. A larger estimate is given in 2 Kings 24:14-16, which refers only to the first deportation 597 B.C.E. Verse 14 gives the numbers as 10,000 men, while verse 16 puts the number at 8,000, an estimate roughly double that of Jeremiah's for all three deportations. Scholars tend to accept Jeremiah's figures as more accurate. In either case, since scholars estimate the total population of the Kingdom of Judah during this time at between 120,000 and 150,000, less than one quarter of the population was actually taken into exile. However, since this included a high percentage of court officials, the priesthood, skilled craftsmen, and other wealthy citizens, the exiles constituted the majority of the cultural elite of nation.

Those who had been deported in 597 had hoped for a speedy return to their homes. They were encouraged in this hope by certain prophets among them, against whom Jeremiah and Ezekiel worked in vain (Jer. 29-29; Ezek. 18, 22). Although most lived in the environs of the great city of Babylon, it is not known whether they formed a close knit community or were scattered throughout the area. One of their places of dwelling was called Tel Aviv (Ezek. 1:3).

As exiles under royal protection, the deportees enjoyed special prerogatives. Indeed, their personal fortunes were undoubtedly better than those who remained behind. Jeremiah's communications with them (Jer. 24:5-7) indicate that that the exiles were permitted to engage in farming, to marry and raise families, buy property, and accumulate wealth. Aside from the issue of sacrifices, which could only be properly offered at the Temple of Jerusalem, they were apparently not hindered in the exercise of their religion. No bloody persecutions are reported.[1]

Nevertheless, it is clear from the writings of the Psalms and later prophets that that many of the exiles indeed felt themselves imprisoned and ill-treated. Psalm 137 expresses these sentiments eloquently:

- By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept when we remembered Zion.

- There on the poplars we hung our harps, for there our captors asked us for songs

- Our tormentors demanded songs of joy; they said, "Sing us one of the songs of Zion!"

- How can we sing the songs of the Lord while in a foreign land?

- If I forget you, O Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its skill.

- May my tongue cling to the roof of my mouth if I do not remember you,

- If I do not consider Jerusalem my highest joy.

Deutero-Isaiah[2] particularly expresses a sense of Israel's degradation as a result of her exile. It describes the nation as a helpless worm (Isa. 41:14) and speaks of her suffering in chains and bondage (42:20-24). These sufferings, however, are not to be understood literally. Rather, they represent the condition of homelessness and servitude to foreign rule, while the territory formerly promised to Israel by God and the holy city itself lay in ruins. Meanwhile, pagans and idolaters could scoff and point to the fall of Jerusalem and its Temple evidence of Yahweh's weakness of Israel's God.

Religious and cultural impact

Many of the exiles, finding themselves in comfortable circumstances, assimilated into Babylonian society in ways that concerned the pious among them. Ezekiel denounced such men as "a rebellious house," and parts of the Book of Isaiah written during exilic times likewise expressed concern over the adoption of Babylonian traditions (Isa. 65:3). Some, however, maintained their faith and others responded to prophetic preaching of repentance (Ezek. 33:31).

Since the Temple was available neither for sacrifices nor festival celebrations, solemn days of penance and prayer commemorated Jerusalem's fall (Zech. 7:3-5, 8:19). The Sabbath took on new emphasis as a day of contemplation, prayer, and sacred rest. Circumcision, too, grew in significance as the special mark of the Israelites in the midst of a foreign people. The prophetic emphasis on works of morality and charity came to the fore, since the priestly functions were, for the moment at least, irrelevant. In response to those who feared that the "sins of the fathers" would be visited upon the sons for the full four generations promised by the Book of Deuteronomy (5:5), Ezekiel promised that "(The son) will not die for his father's sin; he will surely live. But his father will die for his own sin" (Ezek. 19:17-18). Deutoero-Isaiah, meanwhile, expanded the concept of God's special blessing on Israel to include the eventual recognition of Yahweh even by the Gentiles (Isa. 49:22)

The profession of the scribes, often themselves priests learned in the law, also grew in importance during the exile. A more modern Hebrew script was adopted during this period, replacing the traditional Israelite script. Historical writings were compiled and revised in accordance with the emerging priestly consensus, based especially on the historical conception expressed in the Book of Deuteronomy. In this view, the calamities that had befallen the people of Israel and Judah must be accepted by the exiles as a punishment for their sins, especially the sin of idolatry. At the same time, the hope was expressed that a resurrected Jewish people, a holy remnant risen from the grave of exile, would one day return to Jerusalem, rebuild the Temple, and once and for all live in accordance with the Law of Moses.

At the same time, the Jews' exposure to Babylonian literature and traditions served to broaden their viewpoint to include new concepts formerly not strongly evident in the literature of ancient Israel, among them:

- The concept of Satan as God's adversary

- The idea of an angelic hierarchy under God rather than the more ancient idea of an assembly of the gods with Yahweh/Elohim as the supreme deity

- The idea of absolute monotheism, as opposed to the idea that Yahweh was the special god of Israel, but not necessarily the only God

- The related idea of universalism: that not only the Jews, but all people, must honor God

The Jews were also apparently influenced by the wisdom literature of Babylon, expressing a less black-and-white approach to the concept of spiritual wisdom—as expressed for example in the Book of Proverbs with its promises of blessings to righteous and suffering to the wicked. The newer type of wisdom literature expressed a more nuanced and realistic viewpoint, some might even say skeptical, as exemplified by Ecclesiastes and Job.

Finally, some scholars opine that the Babylonian tradition may even have influenced the origin story of Genesis 1, which mythologists believe to be a reworking of the Babylonian cosmology portrayed in the Enuma Elish.

The Return

After the overthrow of Babylon by the Persians, Cyrus instituted a major shift in religious policy, encouraging the priests who had been forced into exile by his predecessors to return to their native lands, install captured religious icons in their proper temples, and minister to the spiritual needs of the peoples. He thus gave the Jews permission to return to Jerusalem in 537 B.C.E. The Book of Ezra reports that 42,360 availed themselves of the privilege, including women, children and slaves, finally completing a long and dreary journey of four months from the banks of the Euphrates to Jerusalem.

Under the Babylonian-appointed governor Zerubbabel, chosen in part because of his Davidic lineage, the Temple foundation would soon be laid, and—just as important—the sacrificial rituals were once against offered. The returning exiles poured their gifts into the sacred treasury with great enthusiasm (Ezra 2). They erected and dedicated the altar of God on the exact spot where it had formerly stood and cleared away the charred heaps of debris which occupied the site. In 535 B.C.E., among great public excitement, the foundations of the second temple were laid. However, its poor appearance was regarded with mingled feelings by the spectators (Haggai 2:3).

Seven years after this Cyrus the Great died (2 Chron. 36:22-23). Mistrust of the non-Jewish populations and various political intrigues caused the rebuilding to cease for a time, but under Darius I of Persia, the work was resumed and carried forward to its completion (Ezra 5:6-6:15). It was ready for consecration in the spring of 516 B.C.E., more than 20 years after the return from captivity.

Jews and Samaritans

When the Jews[3] returned home, they found a mixture of peoples practicing a religion very similar to their own. These people, who came to be known as Samaritans, worshiped Yahweh and honored the Law of Moses as they understood it, but many had intermarried with non-Israelite peoples who had immigrated to Judah and Israel in the wake of the Assyrian and Babylonian policy of forcing conquered peoples into exile. Moreover, some of them had established altars and were offering sacrifices outside of Jerusalem, considered a sin by the spiritual leaders of the exiles.

Zerubbabel and the Jewish elders therefore rebuffed offers from the local inhabitants to help rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem. Ezra and Nehemiah even went so far as to require those who had intermarried to divorce their foreign wives and disown their children in order to be included in the assembly of the Jews. Hostility grew between the returning Jews and the Samaritans. For much of the period from this point until the Common Era, Judea remained a smaller and less influential province than did its northern neighbor, Samaria.

Lasting Impact

Nevertheless, once the Temple of Jerusalem was rebuilt, it became the rallying point of the Jewish people, spawning a tradition which, unlike its Samaritan counterpart, has survived with a large worldwide following into the current era. The paradoxical combination of ethnic purity and universalism that evolved during the Babylonian exile resulted in a religious spirit that survived both the later expulsions of Jews from Jerusalem and their being scattered throughout the world for the last two millennia. The tradition of Jewish ethical monotheism also inspired two other world religions: Christianity and Islam. It may be one of history's great ironies—or perhaps one should say one of God's most dramatic twists of fate—that out of Israel's most tragic moment, its lasting legacy would be born.

Notes

- ↑ Exceptions may be noted in the Book of Daniel, which portrays Nebuchadrezzar as persecuting certain Jews. However, the historicity of this account is questioned.

- ↑ Deutero-Isaiah is the name give to author(s) of those parts of the Book of Isaiah believed to have been written during the Babylonian Exile and later included as part of Isaiah's work.

- ↑ From this point on, we may truly speak of "Jews" rather than "Israelites," since the basic precepts and tradition of Judaism were now firmly in place.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cahill, Thomas. The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels. New York: Anchor Books, 1999. ISBN 978-0385482493

- Grayzel, Solomon. A History of the Jews: From the Babylonian Exile to the Present. Jewish Publication Society, 1968. ISBN 978-0999163368

- Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews. Harper Perennial; Reprint edition, 1988. ISBN 978-0060915339

The above article may incorporate text from the public domain 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica and may be adapted in part from an article originally appearing in the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, also now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved August 26, 2023.

- The Jewish Temples: The Babylonian Exile (597 - 538 B.C.E.) Jewish Virtual Library

- The Babylonian Exile of Israel Biblical Studies

- Babylonian Exile and Beyond Boston University

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.