Baseball

Baseball is a team sport popular in North America, Latin America, the Caribbean, and East Asia. The modern game was developed in the United States from early bat-and-ball games played in Britain and is known as the "national pastime" of the United States, although American football may arguably draw more fans and television viewership.

Baseball is a rare sport in which there is no time limit for play and the defensive side controls the ball. The game also involves a unique combination of individual competitiveness between pitcher and batter and total strategic involvement of the team when the ball is put in play. When played on a high level, baseball involves many subtle adjustments on defense, often depending on the presence of base runners; specialized pitches that vary in movement and velocity; arcane signals; and the execution of precise offensive plays for strategic objectives.

Played upon a diamond-shaped field, a team scores only when batting, by advancing counter-clockwise past a series of bases arranged at the corners. Batters face opposing pitchers and are retired with three strikes, either swung and missed, fouled out of play, or called by the umpire. A batter can take first base either through safely hitting or through a "walk" of four balls called by the umpire. Three outs retire the offensive side and each side has nine "innings," or turns, to score runs.

Baseball is an endearing part of American life in part because of its legendary, larger-than-life players, above all Babe Ruth, perhaps the grandest figure in U.S. sports history; and the distinctive, asymmetric ballparks from baseball's earlier eras. The history of the game and reverence for the accomplishments of the game's greatest stars have drawn generations of fans into endless debates, although rule changes have made statistical comparisons effectively pointless.

Once a populist sport that thrived on fierce competition, the game has always had a laissez-faire relationship with rules. Sharpened spikes to intimidate (and injure) defensive players, illegal "spitballs," loaded bats, and interference with play by fans and players have been ubiquitous throughout the game's history. The use of steroids by some players to enhance performance is a recent, egregious violation of fair play for competitive advantage, rightly censured by fans, sports writers, and baseball management.

Baseball also reflected society's prejudices, establishing a strict color line excluding black athletes from professional competition from the 1880s until the historic signing of Jackie Robinson by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Like other professional sports, baseball has combined sport with consumerism. Star athletes often earn more from product endorsements than on-field play, and salaries for even journeyman players are often in the millions of dollars. An enduring part of the fabric of life where the game is played, baseball at its best encourages sportsmanship, teamwork, individual excellence, and appreciation of the sport's legends, enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

History

Origins of baseball

The distinct evolution of baseball from among the various bat-and-ball games is difficult to pin down. However, it is generally agreed that modern baseball is an American development from earlier British games, such as rounders, with possible influences from cricket.

The earliest known mention of the sport is in a 1744 British publication, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book by John Newbery. It contains a wood-cut illustration of boys playing "base-ball" (showing a set-up similar to the modern game, yet significantly different) and a rhymed description of the sport.

The earliest known American reference to the game was published in a 1791 Pittsfield, Massachusetts bylaw. The city statute proclaimed that the playing of baseball was prohibited within 80 yards of Pittsfield's new meeting house (in an effort to protect its windows).[1]

Alexander Cartwright had a hand in compiling and publishing an early list of rules in 1845 (the so-called Knickerbocker Rules)[2] to meet the demands of the already popular sport, and today's rules of baseball have evolved from them.

History of baseball in the United States

As far back as the 1870s, American newspapers were referring to baseball as "The National Pastime" or "The National Game." An award-winning account of the origins of the game is David Block's Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game (2005). The publisher's description of the book notes:

David Block looks into the early history of the game and of the 150-year-old debate about its beginnings. He tackles one stubborn misconception after another, debunking the enduring belief that baseball descended from the English game of rounders and revealing a surprising new explanation for the most notorious myth of all—the Abner Doubleday–Cooperstown story.[3]

In short, the debate on the game's origins may never be settled to everyone's satisfaction.

Another early mention of the game can be found in an 1886 edition of Sporting Life magazine, in a letter from Dr. Matthew Harris of Boston, Massachusetts, formerly of St. Marys, Ontario, who details a base ball game played in Beachville, Ontario, on June 4, 1838—Militia Muster Day.

Professional baseball began in the United States around 1865, and the National League was founded in 1876 as the first true major league, quickly producing famous players such as Cap Anson. Several other major leagues formed and failed, but in 1901 the American League, originating from the minor Western League (1893), did succeed. While the two leagues were rivals who actively fought for the best players, often disregarding one another's contracts and engaging in bitter legal disputes, a modicum of peace was established in 1903, and they began playing a World Series that year. The next year however, John McGraw, manager of the National League Champion New York Giants, refused to participate in the World Series against the American League champion Boston Pilgrims, because McGraw refused to recognize the American League. The following year, McGraw relented and the Giants played the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

Compared to modern times, games in the early part of the twentieth century were lower scoring and pitchers were more successful. The "inside game," whose nature was to "scratch for runs," was played more violently and aggressively than it is today. Ty Cobb said of his era, "Baseball is something like a war!" This period, which has since become known as the "dead-ball era," ended in the 1920s with several rule changes that gave advantages to hitters and aided the rise of the legendary baseball player Babe Ruth, who became the first power hitter.

During the first half of the twentieth century, a "gentlemen's agreement" created a color line that effectively barred African-American players from the major leagues (though not Native Americans, oddly enough), resulting in the formation of several Negro Leagues. Finally in 1947, Major League Baseball's color barrier was broken when Jackie Robinson was signed by the National League's Brooklyn Dodgers. Although it was not instantaneous, baseball has since become fully integrated.

By the middle of the century, major league baseball had expanded to the Western United States. It was a time when pitchers dominated and scoring became so low in the American League that the designated hitter was introduced in 1973. This rule now constitutes the primary difference between the two leagues, although the MLB instituted designated hitter in 2020 as part of its health and safety protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic.[4]

Despite the popularity of baseball, and the attendant high salaries relative to those of average Americans, the players have become unsatisfied from time to time, believing that the owners had too much control. Various job actions have occurred throughout the game's history. Players on specific teams occasionally attempted strikes, but usually came back when their jobs were sufficiently threatened. The alleged throwing of the 1919 World Series and the "Black Sox scandal," were in some sense a "strike" or at least a rebellion by the ballplayers against a perceived stingy owner. Generally though, the strict rules of baseball contracts tended to keep the players "in line."

This began to change in the 1960s when former United Steelworkers president Marvin Miller became president of the Baseball Players Union. The union became much stronger than it had been previously, especially when the reserve clause (which prohibited players from signing with a new team after their current contract expired) was effectively nullified in the mid-1970s. A series of strikes and lockouts began in baseball, affecting portions of the 1972 and 1981 seasons and culminating in the infamous 1994 baseball strike that led to the cancellation of the World Series and carried over into 1995 before it was finally settled.

The players typically got what they demanded, but the popularity of baseball diminished greatly as a result of the strike, and fans were slow to return. Cal Ripken's record-breaking 2,131st consecutive game in 1995 was a feel-good moment that helped boost interest in the sport. The great home run race of 1998 between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa truly turned interest around, captivating fans all summer. As with other times when adversity threatened the game, positive on-field events triggered a renewed surge in baseball's popularity in America.

International developments

Professional baseball leagues began to form in countries outside of America in the 1920s and 1930s, including the Netherlands (formed in 1922), Japan (1936), and Australia (1934). Today, Venezuela (1945), Italy (1948), the whole of Europe (1953), Korea (1982), Taiwan (1990), and mainland China (2003) all have professional leagues. Countries in the Caribbean, notably the Dominican Republic and Cuba, have a strong baseball culture, contributing many players to the Major Leagues.

However, the leagues in Australia, Italy and the United Kingdom have generally had a niche appeal compared to the leagues in Asia and Venezuela. Only now is the sport beginning to broaden in scope in those nations, most notably in Australia, which won a surprise silver medal in the 2004 Olympic Games. Israel is trying to form a professional baseball league with the help of American émigrés. Canada has a franchise in Major League Baseball as well—the Toronto Blue Jays. Competition between national teams, such as in the World Cup of Baseball and the Olympic baseball tournament, has been administered by the International Baseball Federation since its formation in 1938. As of 2004, this organization has 112 member countries. The new World Baseball Classic, first held in March 2006, seems likely to have a much higher profile than previous tournaments, owing to the participation for the first time of a significant number of players from the United States major leagues.

The 117th meeting of the International Olympic Committee, held in Singapore in July 2005, voted not to hold baseball and softball tournaments at the 2012 Summer Olympic Games, but they will remain Olympic sports during the 2008 Summer Olympic Games and will be put to vote again for each succeeding Summer Olympics. The elimination of baseball and softball from the 2012 Olympic program enabled the IOC to consider adding two other sports to the program instead, but no other sport received a majority of votes favoring its inclusion. While baseball's lack of major appeal in a significant portion of the world was a factor, a more important factor was the unwillingness of Major League Baseball to have a break during the Games so that its players could participate, something that the National Hockey League now does during the Winter Olympic Games. It is believed it would be more difficult to accommodate such a break in MLB because of the seasonal nature of baseball and the high priority baseball fans place on the integrity of major-league statistics from one season to the next.

Gameplay

The complete Official Rules of baseball can be found at the United States Official Major League website. For a simplified version of the rules go to Official Rules.

General structure

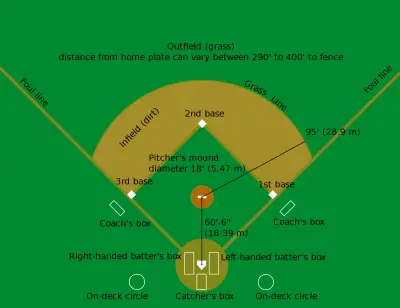

Baseball is played between two teams of nine players each on a baseball field, under the authority of one or more officials called umpires. There are usually four umpires in major league games; up to six (and as few as one) may officiate depending on the league and the importance of the game. There are four bases. Numbered counter-clockwise, first, second and third base are cushions (sometimes informally referred to as bags) shaped as 15-inch (38 centimeters) squares which are raised a short distance above the ground; together with home plate, the fourth "base," they form a square with sides of 90 feet (27.4 meters) called the diamond. Home base (plate) is a pentagonal rubber slab known simply as home. The field is divided into two main sections:

- The infield, containing the four bases, is for defensive and offensive purposes bounded by the foul lines and the grass line (see figure). However, the infield technically consists of only the area within and including the bases and foul lines.

- The outfield is the grassed area beyond the infield grass line (for general purposes; see above under infield), between the foul lines, and bounded by a wall or fence. Again, there is a technical difference; properly speaking, the outfield consists of all fair ground beyond the square of the infield and its bases. The area between the foul lines, including the foul lines (the foul lines are in fair territory), is fair territory, and the area outside the foul lines is foul territory.

The game is played in nine innings (although it can be played with fewer, such as it is in little league) in which each team gets one turn to bat and try to score runs while the other pitches and defends in the field. An inning is broken up into two halves in which the away team bats in the top (first) half, and the home team bats in the bottom (second) half. In baseball, the defense always has the ball—a fact that differentiates it from most other team sports. The teams switch every time the defending team gets three players of the batting team out. The winner is the team with the most runs after nine innings. If the home team is ahead after the top of the ninth, play does not continue into the bottom half. In the case of a tie, extra innings are played until one team comes out ahead at the end of an inning. If the home team takes the lead anytime during the bottom of the ninth or of any inning thereafter, play stops and the home team is declared the winner.

The basic contest is always between the pitcher for the fielding team, and a batter. The pitcher throws—pitches—the ball towards home plate, where the catcher for the fielding team waits (in a crouched stance) to receive it. Behind the catcher stands the home plate umpire. The batter stands in one of the batter's boxes and tries to hit the ball with a bat. The pitcher must keep one foot in contact with the top or front of the pitcher's rubber—a 24-inch by 6-inch (61 cm x 15 cm) plate located atop the pitcher's mound—during the entire pitch, so he can only take one step backward and one forward in delivering the ball. The catcher's job is to receive any pitches that the batter does not hit and to "call" the game by a series of hand movements that signal to the pitcher what pitch to throw and where. If the pitcher disagrees with the call, he will "shake off" the catcher by shaking his head; he accepts the sign by nodding. The catcher's role becomes more crucial depending on how the game is going, and how the pitcher responds to a given situation. Each pitch begins a new play, which might consist of nothing more than the pitch itself.

Each half-inning, the goal of the defending team is to get three members of the other team out. A player who is out must leave the field and wait for his next turn at bat. There are many ways to get batters and baserunners out; some of the most common are catching a batted ball in the air, ground outs, tag outs, force outs, and strikeouts. After the fielding team has put out three players from the opposing team, that half of the inning is over and the team in the field and the team at bat switch places; there is no upper limit to the number that may bat in rotation before three outs are recorded. Going through the entire order in an inning is referred to as batting around. It is indicative of a high scoring inning. A complete inning consists of each opposing side having a turn (three outs) on offense.

The goal of the team at bat is to score more runs than the opposition; a player may do so only by batting, then becoming a baserunner, touching all the bases in order (via one or more plays), and finally touching home plate. To that end, the goal of each batter is to enable baserunners to score or to become a baserunner himself. The batter attempts to hit the ball into fair territory—between the baselines—in such a way that the defending players cannot get them or the baserunners out. In general, the pitcher attempts to prevent this by pitching the ball in such a way that the batter cannot hit it cleanly or, ideally, at all.

A baserunner who successfully touches home plate after touching all previous bases in order scores a run. In an enclosed field, a fair ball hit over the fence on the fly is normally an automatic home run, which entitles the batter and all runners to touch all the bases and score. A home run hit with all bases occupied ('bases loaded') is called a grand slam.

Fielding team

The squad in the field is the defensive team; they attempt to prevent the baserunners from scoring. There are nine defensive positions; however, only two of the positions have a mandatory location (pitcher and catcher). The locations of the other seven fielders are not specified by the rules, except that at the moment the pitch is delivered they must be positioned in fair territory and not in the space between the pitcher and the catcher. These fielders often shift their positioning in response to specific batters or game situations and they may exchange positions with one another at any time. The nine positions are: pitcher, catcher, first baseman, second baseman, third baseman, shortstop, left fielder, center fielder, and right fielder. Note that, in rare cases, teams may use dramatically differing schemes, such as switching an outfielder for an infielder. Scorekeepers label each position with a number starting with the pitcher (1), catcher (2), first baseman (3), second baseman (4), third baseman (5), shortstop (6), left fielder (7), center fielder (8), and right fielder (9). This convention was established by Henry Chadwick. The reason the shortstop seems out of order has to do with the way fielders positioned themselves in the early years of the game.

The battery

The battery is composed of the pitcher, who stands on the rubber of the mound, and the catcher, who squats behind home plate. These are the two fielders who always deal directly with the batter on every pitch, hence the term "battery," coined by Henry Chadwick and later reinforced by the implied comparison to artillery fire.

The pitcher's main role is to pitch the ball toward home plate with the goal of getting the batter out. Pitchers also play defense by fielding batted balls, covering bases (for a potential tag out or force out on an approaching runner), or backing up throws. The catcher's main role is to receive the pitch if the batter does not hit it. Together with the pitcher and coaches, the catcher plots game strategy by suggesting different pitches and by shifting the starting positions of the other fielders. Catchers are also responsible for defense in the area near home plate.

The infielders

The four infielders are the first baseman, second baseman, shortstop, and third baseman. Originally the first, second and third basemen played very near their respective bases, and the shortstop generally played "in" (hence the term), covering the area between second, third, and the pitchers box, or wherever the game situation required. As the game evolved, the fielding positions changed to the now-familiar "umbrella," with the first and third baseman generally positioned a short distance toward second base from their bases, the second baseman to the right side of second base standing farther away from the base than any other infielder, and the shortstop playing to the left of second base, as seen from the batter's perspective, filling in the gaps.

The first baseman's job consists largely of making force plays at first base on ground balls hit to the other infielders. When an infielder picks up a ball from the ground hit by the batter, he must throw it to the first baseman who must catch the ball while maintaining contact with the base before the batter gets to the base for the batter to be out. The first baseman must be able to catch the ball very well and usually wears a specially designed mitt. The first baseman also fields balls hit near first base. The first baseman also has to receive throws from the pitcher in order to tag runners out who have reached base safely. The position is less physically challenging than the other positions, but there is still a lot of skill involved. Infielders don't always make good throws to first base, so it is the first baseman's job to field any ball thrown toward him cleanly. Older players who can no longer fulfill the demands of their original positions also often become first basemen.

The second baseman covers the area to the first-base side of second base and provides backup for the first baseman in bunt situations. He also is a cut-off for the outfield. This is when the outfielder doesn't have to throw the full distance from him/her to the base, but just to the cut-off.

The shortstop fills the critical gap between second and third bases—where right-handed batters generally hit ground balls—and also covers second or third base and the near part of left field. This player is also a cut-off for the outfield. This position is the most demanding defensively, so a good shortstop doesn't need to necessarily be a good batter.

The third baseman's primary requirement is a strong throwing arm, in order to make the long throw across the infield to the first baseman. Quick reaction time is also important for third basemen, as they tend to see more sharply hit balls than the other infielders, thus the nickname for third base as the "hot corner."

The outfielders

The three outfielders, left fielder, center fielder, and right fielder, are so named from the catcher's perspective looking out onto the field. The right fielder generally has the strongest arm of all the outfielders due to the need to make throws on runners attempting to take third base. The center fielder has more territory to cover than the corner outfielders, so this player must be quick and agile with a strong arm to throw balls to the infield; as with the shortstop, teams tend to emphasize defense at this position. Also, the center fielder is considered the outfield leader, and left- and right-fielders often cede to his direction when fielding fly balls. Of all outfielders, the left fielder often has the weakest arm, as they generally do not need to throw the ball as far in order to prevent the advance of any baserunners. The left fielder still requires good fielding and catching skills, and tends to receive more balls than the right fielder due to the fact that right-handed hitters, who are much more common, tend to pull the ball into left field. The left fielder also backs up third base on pick-off attempts from the catcher.

Defensive strategy

Pitching

Effective pitching is vitally important to a baseball team, as pitching is the key for the defensive team to retiring batters and to preventing runners from getting on base. A full game usually involves over one hundred pitches thrown by each team. However, most pitchers begin to tire before they reach this point. In previous eras, pitchers would often throw up to four complete games (all nine innings) in a week.

Multiple pitchers are often needed in a single game, including the starting pitcher and relief pitcher(s). Pitchers are substituted for one another like any other player (see below), and the rules do not limit the number of pitchers that can be used in a game; the only limiting factor is the size of the squad. In general, starting pitchers are not used in relief situations except sometimes during the post-season when every game is vital. If a game runs into many extra innings, a team may well empty its bullpen. If it then becomes necessary to use a position player as a pitcher, major league teams generally have certain players pre-designated as emergency relief pitchers to avoid the embarrassment of using a less skillful player.

In baseball's early years, squads were smaller and relief pitchers were relatively uncommon; the starting pitcher would normally remain for the entire game unless he was either thoroughly ineffective or became injured. With new advances in medical research and thus a better understanding of how the human body functions and tires out, starting pitchers tend more often to throw fractions of a game (typically 6 or 7 innings depending on their performance) about every five days (though a few complete games do still occur each year). Today, there is a much greater emphasis on pitch count (100 being the "magic number" in general) and each team will frequently use from two to five pitchers over the course of the game.

Although a pitcher can only take one step backward and one forward while delivering the ball, the pitcher has a great arsenal at his disposal in the variation of location, velocity, movement, and arm location (see types of pitches). Most pitchers attempt to master two or three types of pitches while some pitchers throw up to six types of pitches with varying degrees of control. Common pitches include a fastball, which is the ball thrown at just under maximum velocity; a curveball, which is made to curve by rotation imparted by the pitcher; and a change-up, which seeks to mimic the delivery of a fastball but arrives at a significantly lower velocity.

To illustrate pitching strategy, consider the "fastball/change-up" combination: The average major-league pitcher can throw a fastball around 90 miles per hour (145 km/h), and a few pitchers have even exceeded 100 miles per hour (161 km/h). The change-up is thrown somewhere between 75 to 85 miles per hour (121 to 137 km/h). Since the batter's timing is critical to hitting a pitch, a batter swinging to hit what looks like a fastball, would be fooled significantly (possibly resulting in a swing and miss,) when the pitch turns out to be a much slower change-up.

Some pitchers choose to throw using the submarine style, a very efficient sidearm or near-underhand motion. Pitchers with a submarine delivery are often very difficult to hit because of the angle and movement of the ball once released. Walter Johnson, who threw one of the fastest fastballs in the history of the game, threw sidearm (though not submarine) rather than overhand. True underhanded pitching is not illegal in Major League Baseball. However, it is difficult to generate enough velocity and movement with the underhand motion.

Fielding strategy

Only the pitcher's and catcher's locations are fixed, and then only at the beginning of each pitch. Thus, the players on the field move around as needed to defend against scoring a run. Many variations of this are possible, as location depends upon the situation. Circumstances such as the number of outs, the count (balls and strikes) on the batter, the number and speed of runners, the ability of the fielders, the ability of the pitcher, the type of pitch thrown, and the inning cause the fielders to move to more strategic locations on the field. Common defensive strategies include: playing for the bunt, trying to prevent a stolen base, moving to a shallow position to throw out a runner at home, playing at double play depth, and moving fielders to locations where hitters are most likely to hit the ball.

Team at bat

Batters and runners

The ultimate goal of the team at bat is to score runs. To accomplish this feat, the team at bat successively (in a predetermined order called a lineup or batting order) sends its nine players to the batter's box (adjacent to home plate) where they become batters. Each team sets its batting lineup at the beginning of the game. Changes to the lineup are tightly limited by the rules of baseball and must be communicated to the umpires, who have the substitutions announced for the opposing team and fans (see Substitutions below).

A batter's turn at the plate is called a plate appearance or an at-bat. Batters advance to the bases in a variety of ways: hits, walks, hit-by-pitches, and a few others. When the batter hits a fair ball, he must run to first base and may continue or stop at any base unless he is put out. A successful hit occurs when the batter reaches a base (not on an error): reaching only first base is a single; reaching second base, a double; third base, a triple; and a hit that allows the batter to touch all bases in order on the same play is a home run, whether or not the ball is hit over the fence. Once a runner is held to a base he may attempt to advance at any time, but is not required to do so unless the batter or another runner displaces him (called a force play). A batter always drops his bat when running the bases so it doesn't slow him down. A line drive is like a fly ball, but the ball is hit with such force that its trajectory seems level to the ground. A batted ball that is not hit into the air and which touches the ground within the infield before it can be caught is called a ground ball or “grounder.” When a ball is hit outside the foul line, it is a foul ball, and requires the batter and all runners to return to their respective bases.

Once the batter and any existing runners have all stopped at a base or been put out, the ball is returned to the pitcher and the next batter comes to the plate. After the opposing team bats in its own order and three more outs are recorded, the first team's batting order will continue again from where it left off.

When a runner reaches home plate, he scores a run and is no longer a base runner. He must leave the playing area until his spot in the order comes up again. A runner may only circle the bases once per plate appearance and thus can score no more than a single run.

Each plate appearance consists of a series of pitches in which the pitcher throws the ball towards home plate while a batter is standing in the batter's box. With each pitch, the batter must decide whether or not to swing the bat at the ball in an attempt to hit it. The pitches arrive quickly, so the decision to swing must be made in less than a tenth of a second, based on whether or not the ball is hittable and in the strike zone, a region defined by the area directly above home plate and between the hollow beneath the batter's knee and the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants. In addition to swinging at the ball, a batter who wishes to put the ball in play may hold his bat over home plate and attempt to tap a pitch lightly; this is called a bunt.

On any pitch, if the batter swings at the ball and misses, he is charged with a strike. If the batter does not swing, the home plate umpire judges whether or not the ball passed through the strike zone. If the ball or any part of it passed through the zone, it is ruled a strike; otherwise, it is called a ball. The number of balls and strikes thrown to the current batter is known as the count; the count is always given balls first (except in Japan, where it is reversed), then strikes (such as 3-2 or "three and two," also known as a "full count," which would be 3 balls and 2 strikes).

If the batter swings and hits a foul ball, he is charged with an additional strike. However, if there are already two strikes, a foul ball leaves the count unchanged (a noted exception to this rule is that a ball bunted foul with two strikes always counts as a strike—meaning a ball bunted into foul territory will result in an out). If a pitch is batted foul or fair and a member of the defensive team is able to catch it before the ball strikes the ground, the batter is declared out. In the event that a bat contacts the ball, but the ball continues sharply and directly to the catcher's mitt and is caught by the catcher, it is a foul tip, which is the same as an ordinary strike.

When three strikes occur on a batter, it is a strikeout and the batter is automatically out unless the pitch is not caught by the catcher or if the pitch bounces before it is caught. It is then ruled a dropped third strike (this is a violation of the third strike rule).[5] If the catcher drops the third strike, the batter is permitted to attempt to advance to first base. In this case, the batter is not out (although the pitcher is awarded a strikeout). The catcher can try to get the batter out by tagging him with the ball or throwing the ball to first base and forcing him out. A famous example of a dropped third strike that dramatically altered the course took place in the 1941 World Series.[6]

On the fourth ball the batter becomes a runner, and is entitled to advance to first base without risk of being put out, called a base on balls or a walk (abbreviated BB). If a pitch touches the batter, the umpire declares a hit by pitch (abbreviated HBP) and the batter is awarded first base unless the umpire determines that the ball was in the strike zone when it hit the batter, or that the batter did not attempt to avoid being hit. In practice, neither exception is ever called unless the batter obviously tries to get hit by the pitch; even standing still in the box will virtually always be overlooked and the batter awarded first. If any part of the catcher or his equipment (mitt, mask, etc.) comes in contact with the batter and/or the batter's bat as the batter is attempting to hit a pitch, the batter is awarded first base, and the play is ruled a "catcher's interference."

Baserunning

Once a batter becomes a runner and reaches first base safely, he is said to be "on" that base until he attempts to advance to the next base, until he is put out, or until the half-inning ends. When comparing two or more runners on the basepaths, the runner farther along is called a lead runner or a preceding runner; the other runner is called a trailing runner or a following runner. Runners on second or third base are considered to be in scoring position since ordinary hits, even singles, will often score them.

A runner legally touching a base is "safe"—he may not be put out. Runners may attempt to advance from base to base at any time (except when the ball is dead), but must attempt to advance when forced—when all previous bases are occupied and the batter becomes a runner. When a ball is hit in the air, a fly ball, and caught by the defending team, runners must return and touch the base they occupied at the time of the pitch—called tagging up—after the ball is first touched. Once they do this, they may attempt to advance at their own risk.

Only one runner may occupy a base at a time. If two runners are touching a base at once, the trailing runner is in jeopardy and will be out if tagged, unless he was forced—in which case the lead runner is out when tagged for failing to reach his force base. Either such occurrence is very rare. Thus, after a play, at most three runners may be on the basepaths, one on each base—first, second, and third. When three runners are on base, this is called bases loaded.

Baserunners may attempt to advance, or steal a base, while the pitcher is throwing a pitch. The pitcher, in lieu of delivering the pitch, may try to prevent this by throwing the ball to one of the infielders in order to tag the runner; if successful, it is called a pick-off. If the runner attempts to steal the next base but is tagged out before reaching it safely, he is caught stealing. An illegal attempt by the pitcher to throw a runner out, among other pitching violations, is called a balk, allowing the runners to advance one base without risk of being put out.

Batting and base running strategy

The goal of each batter is to become a base runner himself (by a base hit, a base on balls, being hit by the pitch, a fielding error, or fielder's choice) or to help move other base runners along (by sacrifice bunt, sacrifice fly, or hit and run).

Batters attempt to "read" pitchers through pre-game preparation by studying the tendencies of pitchers and by talking to other batters that previously have faced the pitcher. While batting, batters attempt to "read" pitches by looking for clues that the pitcher or catcher reveal. These clues (also referred to as "tipping pitches") include movements of the pitchers arms, shoulders, body, etc, or the positioning of the catcher's feet and glove. Batters can attempt to "read" the spin of a ball early in the pitch to anticipate its trajectory. Batters also remain keenly aware of the count during their at bat. The count is considered to be in the batter's favor when there are more balls than strikes (e.g. two balls and no strikes). This puts pressure on the pitcher to throw a strike in order to avoid a walk, so the batter is more likely to get an easier pitch to hit and can look for a particular pitch in a particular zone or take a riskier swing. The count is considered to be in the pitcher's favor when there are fewer balls than strikes (e.g. no balls and two strikes). This gives the pitcher more freedom to try enticing the batter to swing at a pitch outside the strike zone or throwing a pitch that is harder to control (e.g. a curve, slider or splitter) but is also harder to hit. Thus, the batter will take a more conservative swing.

In general, base running is a tactical part of the game requiring good judgment by runners (and their coaches) to assess the risk in attempting to advance. During tag plays, a good slide can affect the outcome of the play. Managers will sometimes simultaneously send a runner and require the batter to swing (a hit-and-run play) in an attempt to advance runners. Often, on a hit-and-run play the batter will try to hit behind the runner by hitting the ball to right field which makes it more likely that the runner will be able to make it to third base, thus taking an extra base.

A batter can also attempt to move a baserunner forward by sacrificing his at-bat. This can be done by bunting the ball, or by hitting a fly ball far enough in the air that a baserunner can advance after the catch, or by simply making contact with the ball on a hit-and-run play.

During the course of play many offensive and defensive players run close to each other, and during tag plays, the defensive player must touch the offensive player. Although baseball is considered a non-contact sport, a runner may be allowed to make potentially dangerous contact with a fielder as part of an attempt to reach a base unless that fielder is fielding a batted ball.[7] A good slide is often more advantageous than such contact, and "malicious" contact by runners is typically prohibited as offensive interference. The most common occurrence of contact of this nature is at home plate between the runner and the catcher, as the catcher is well padded and locked into position on or near the plate and the runner will often try to knock the ball out of the catcher’s hand. Since the catcher is seen (symbolically and literally) as the last line of defense, it seems natural that the more physical play happens here.

Innings and determining a winner

An inning consists of each team having one turn in the field and one turn to hit, with the visiting team batting before the home team. A standard game lasts nine innings, although some leagues (such as high school baseball) use seven-inning games. The team with the most runs at the end of the game wins. If the home team is ahead after eight-and-a-half innings have been played, it is declared the winner and the last half-inning is not played. If the home team is trailing or tied in the last inning and they score to take the lead, the game ends as soon as the winning run touches home plate; however, if the last batter hits a home run to win the game, he and any runners on base are all permitted to score.

If both teams have scored the same number of runs at the end of a regular-length game, a tie is avoided by the addition of extra innings. As many innings as necessary are played until one team has the lead at the end of an inning. Thus, the home team always has a chance to respond if the visiting team scores in the top half of the inning; this gives the home team a small tactical advantage. In theory, a baseball game could go on forever; however, a game might theoretically end if both the home and away team were to run out of players to substitute (see Substitutions). In Major League Baseball, the longest game played was a 26-inning affair between the Brooklyn Robins and Boston Braves on May 1, 1920. The game ended in a 1-1 tie called on account of darkness.

In Major League Baseball, games end with tie scores only because conditions have made it impossible to continue play. A tie game does not count as an official game in the standings unless it is finished later or replayed; however, individual player statistics from tie games are counted. Inclement weather may also shorten games, but at least five innings must be played for the game to be considered official with four-and-a-half innings being enough if the home team is ahead. Previously, curfews and the absence of adequate lighting caused more ties and shortened games. Also, with more modern playing surfaces better able to handle light rains, the process for calling or shortening a game due to weather has changed. It is more common than in the past to delay a game as much as two hours before a cancellation; also, a delay usually does not occur anymore until the rain is moderate-heavy and/or there is standing water on some part of the playing field.

In Japanese baseball, if the score remains tied after nine innings, up to three extra innings may be played before the game is called a tie. Some youth or amateur leagues will end a game early if one team is ahead by ten or more runs, a practice known as the mercy rule or slaughter rule. Rarely, a game can also be won or lost by forfeit.

There is a short break between each half-inning during which the new defensive team takes the field and the pitcher warms up. Traditionally, the break between the top half and the bottom half of the seventh inning is known as the seventh-inning stretch. During the "stretch," fans in the United States often sing the chorus of Take Me Out to the Ball Game, and since September 11, 2001, God Bless America has also become common.

Substitutions

Each team is allowed to substitute for any player at any time the ball is dead. A batter who replaces another batter is referred to as a pinch hitter; similarly, a pinch runner may be used as a replacement for a baserunner. Any replacement is a permanent substitution; the replaced player may not return to the game.

It is common for a pitcher to pitch for several innings and then be removed in favor of a relief pitcher. Because pitching is a specialized skill, most pitchers are relatively poor hitters; it is common to substitute for a pitcher when he is due to bat. This pinch hitter is typically then replaced by a relief pitcher when the team returns to the field on defense, but more complicated substitutions are possible, most notably the double switch.

Many amateur leagues allow a starting player who was removed to return to the game in the same position in the batting order under a re-entry rule. Youth leagues often allow free and open substitution to encourage player participation.

Most leagues, notably American League, allow a designated hitter, a player whose sole purpose is to hit when it would normally be the pitcher's turn. This is not considered a substitution but rather a position, albeit a purely offensive one. A designated hitter does not play in the field on defense and may remain in the game regardless of changes in pitchers.

Rosters

During the course of a game, each baseball team has players that are an active part of the game, described as in the game, and players that are not, dubbed on the bench. The players on the bench are needed in case of injuries and to make strategic pitching, fielding, and batting substitutions. To keep the game fair, each team is limited to a fixed number of players. That number is dictated by the rules of the game. In the major leagues, a team may have a maximum of 25 men on a roster from Opening Day until August 31. After that, teams may call up additional personnel, up to a maximum of 40 players on the active roster, with the exception of the postseason, where rosters are fixed at 25 men.

Other personnel

Each team is run by a manager, whose primary responsibilities during the game include assigning players to fielding positions, determining the lineup, deciding how to substitute players, and, most importantly, choosing the course of strategy throughout the game. Managers are also assisted by coaches in helping players to develop their skills. When a team is at-bat, they will position a coach or manager in each coach's box, referred to as the first and third base coaches. These coaches must help the players decide whether they should try to run to the next base; also, the coaches will signal plays to the batter and runners. Baseball is unique in that the manager and coaches all wear numbered uniforms similar to those of the players.

Any baseball game involves one or more umpires, who make rulings on the outcome of each play. At a minimum, one umpire will stand behind the catcher to have a good view of the strike zone and call each pitch a ball or a strike. Additional umpires may be stationed near the bases to more easily call the plays in the field. In Major League Baseball, four umpires are used for each game, one near each base. In the All-Star game and playoffs, six umpires are used: one at each base and two in the outfield along either foul line.

Another notable role in baseball is that of the official scorer. The results of baseball games are summarized in tables called box scores. The scorer is responsible for a number of judgments that go into the box score. For example, if a batted ball is misplayed by a fielder, the scorer may choose to charge the fielder with an error instead of crediting the batter with a hit. Within certain guidelines, the scorer also determines which pitchers are credited with winning and losing the game, and whether a relief pitcher will be awarded a hold or save; specific situations in which a relief pitcher keeps a lead intact for his team.

Baseball's unique style

Baseball is unique among American sports in several ways. This uniqueness is in large part because of its longstanding appeal and strong association with the American psyche. The philosopher Morris Raphael Cohen described baseball as a national religion. Many people believe that baseball is the ultimate combination of skill, timing, athleticism, and strategy. Yogi Berra, a Hall of Fame baseball player, once said: "Baseball is 90 percent mental—the other half is physical." Although these elements all contribute to baseball's appeal in American culture, they are also shared by its cousin game cricket. In many Commonwealth nations, cricket and the culture surrounding it hold a similar appeal to baseball's in American culture.

The lure of baseball is in its subtleties: situational defense, pitch location, pitch sequence, statistics, ballparks, history, and player personalities. It has been noted that the game itself has no time limit, and its playing surface, rather than rigidly rectangular and standardized, extends theoretically to eternity from a single point (home plate) to beyond its own fences (if only a batter could hit a ball hard enough to break the escape velocity of Earth). For the avid fan, the game—even during its slowest points—is never boring because of these nuances. Therefore, a full appreciation of baseball naturally requires some knowledge of the rules; it also requires deep observation of those endearing and enduring qualities that give baseball its unique style.

Time element

American football, basketball, ice hockey and soccer all use a clock and games often end by a team killing the clock rather than competing directly against the opposing team. In contrast, baseball has no clock; a team cannot win without getting the last batter out and rallies are not constrained by time.

In recent decades, observers have criticized professional baseball for the length of its games, with some justification as the time required to play a baseball game has increased steadily through the years. One hundred years ago, games typically took an hour and a half to play; in 2004, the average major league baseball game lasted two hours and 47 minutes. This is due to increased offense, more pitching changes, a slower pace of play, and longer breaks between half-innings for television commercials

In response, Major League Baseball has instructed umpires to be stricter in enforcing speed-up rules and the size of the strike zone. Although the official rules specify that when the bases are empty, the pitcher should deliver the ball within 20 seconds of receiving it (with the penalty of a ball called if he fails to do so), this rule is rarely, if ever, enforced.

Individual and team

Baseball is fundamentally a team sport—even two or three Hall of Fame-caliber players are no guarantee of a pennant—yet it places individual players under great pressure and scrutiny. The pitcher must make good pitches or risk losing the game; the hitter has a mere fraction of a second to decide what pitch has been thrown and whether or not to swing at it. While their respective managers and/or coaches can sometimes signal players regarding the strategies the manager wants to employ, no one can help the pitcher while he pitches or the hitter while he bats. If the batter hits a line drive, the outfielder, as the last line of defense, makes the lone decision to try to catch it or play it on the bounce. Baseball history is full of heroes and goats —men who in the heat of the moment (the "clutch") distinguished themselves with a timely hit or catch, or an untimely strikeout or error.

The uniqueness of each baseball park

Unlike the majority of sports, baseball parks do not have to follow a strict set of guidelines. With the exception of the strict rules on the dimensions of the infield, discussed above, the official rules simply state that fields built after June 1, 1958 must have a minimum distance of 325 feet (99 meters) from home plate to the fences in left and right field and 400 (121 meters) feet to center. This rule (a footnote to official rule 1.04) was passed specifically in response to the fence at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, which was 251 feet (77 meters) to the left field pole, 1 foot (0.3 meters) over the bare minimum required by the rules.[8] However, major league teams often skirt this rule. For example, Minute Maid Park's left field is only 315 feet (96 meters),[9] and with a fence much lower than the famous "Green Monster" at Fenway Park.[10] And there are no rules at all regulating the height of "fences, stands or other obstructions," other than the assumption that they exist. Because of this flexibility, there are all sorts of variations in parks, from different lengths to the fences to uneven playing surfaces to massive or minimal amounts of foul territory. All of these factors, as well as local variations in altitude, climate and game scheduling, can affect the nature of the games played at those ballparks; a park may even be referred to as either a "pitcher's park" or a "hitter's park," depending on which side benefits more from the unique factors present. Wrigley Field, strangely enough, can be either, depending on the wind direction at any given time.[11]

Statistics

Statistics are very important to many sports and perhaps especially to baseball. Statistics have been kept for the major leagues since their creation. General managers, baseball scouts, managers, and players alike study player statistics to help them choose various strategies to best help their team.

Traditionally, statistics like a batter's batting average—the number of hits divided by the number of at bats—and a pitcher's earned run averages —approximately the number of runs given up by a pitcher per nine innings—have governed the statistical world of baseball. However, the advent of sabermetrics has brought an onslaught of new statistics that perhaps better gauge a player's performance and contributions to his team from year to year.

Some sabermetrics have entered the mainstream baseball statistic world. On-base plus slugging (OPS) is a somewhat complicated formula that gauges a hitter's performance better than batting average. It combines the hitter's on base percentage—hits plus walks plus hit by pitches divided by at bats plus bases on balls plus hit by pitches plus sacrifice flies—with their slugging percentage—total bases divided by at bats. Walks plus hits per inning pitched (or WHIP) gives a good representation of a pitcher's abilities; it is calculated exactly as its name suggests.

Also important are more specific statistics for particular situations. For example, a certain hitter's ability to hit left-handed pitchers might cause his manager to give him more chances to face lefties. Some hitters hit better with runners in scoring position, so an opposing manager might elect to intentionally walk him in order to face a poorer hitter.

Popularity

Baseball is most popular in East Asia and the United States, although it is also popular in South America, mainly in the northern portion of the continent, as well as Brazil. In Japan, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Panama, Venezuela, Nicaragua, South Korea, and Taiwan, it is one of the most popular sports. The United States is the birthplace of baseball and it has long been regarded as more than just a "major sport"—it has been considered for decades the national pastime and Major League Baseball has been given a unique monopoly status by the United States Congress. Although three of the four most popular sports in North America are ball games—baseball, basketball and American football—baseball's popularity grew so great that the word "ballgame" in the United States almost always refers to a game of baseball, and "ballpark" to a baseball field (except in the South, where "ballgame" is also used in association with football).

Baseball has often been a barometer of the fabled American "melting pot," as immigrants from different regions have tried to "make good" in various areas including sports. In the nineteenth century, baseball was populated with many players of Irish or German extraction. A number of Native Americans had successful careers especially in the early 1900s. Italians and Poles appeared on many rosters during the 1920s and 1930s. Black Americans came on strong starting in the late 1940s after the race barriers had been lifted, and continue to form a significant contingent. Hispanics had started to make the scene by the 1960s and became a dominant force by the 1990s. In the twenty-first century, East Asians have been appearing in increasing numbers.

While baseball is arguably the most popular sport in the United States and is certainly one of the two most popular along with football, it is difficult to determine which is more popular because of the wide discrepancy in number of games per season. For example, the total attendance for Major League Baseball games is roughly equal to that of all other American professional team sports combined, but football gets higher television ratings—both a function in part of the long (162-game) baseball season and short (16-game) football season. However, among adults that follow one or more sports, 46 percent name either college or pro football as their favorite sport, as opposed to baseball at just under 15 percent.

Organized leagues

Baseball is played at a number of levels, by amateur and professionals as well as the young and the old. Youth programs use modified versions of adult and professional baseball rules, which may include a smaller field, easier pitching (from a coach, a tee, or a machine), less contact, base running restrictions, limitations on innings a pitcher can throw, liberal balk rules, and run limitations among others. Since rules vary from location-to-location and among the organizations, coverage of the nuances in those rules is beyond this article.

Following is a list of organized leagues:

- Youth Leagues

- Little League, a youth program, headquartered in Williamsport, Pennsylvania (USA).

- Pony Baseball, a youth program, headquartered in Washington, Pennsylvania (USA).

- Dizzy Dean Baseball a youth program in the USA.

- American Legion Baseball, a youth program, headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana (USA).

- USSSA Baseball a youth and adult program, headquartered in Kansas City, Missouri (USA).

- Ripken Baseball, a youth program, headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland (USA).

- Babe Ruth League, a youth program, headquartered in Trenton, New Jersey (USA).

- Moberly Midget League a youth program headquartered in Moberly, Missouri (USA).

- High School

- In the USA, the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) and each state association governs the play of baseball at the high school level.

- Collegiate Level

- National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), including NCAA Division I and the College World Series, are collegiate level baseball programs played in the USA.

- National Club Baseball Association (NCBA)

- International Competition

- Many international baseball events are coordinated by the International Baseball Federation, including World Cup of Baseball and The World Baseball Classic.

- Professional baseball

- Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States;

- Minor League baseball in the United States;

- Negro League baseball, defunct since 1958, in the United States.

- All-American Girls Professional Baseball League

Notes

- ↑ Associated Press, Pittsfield uncovers earliest written reference to game ESPN.com, May 11, 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ↑ Knickerbocker Baseball Rules Baseball Almanac. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ↑ David Block, Baseball Before We Knew It (Bison Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0803262553).

- ↑ Designated Hitter Rule MLB. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ↑ The "third strike rule," which has been on the books since at least the time of the Knickerbocker Rules, is that the batter can try to advance to first base on the third strike if the third strike is not caught. However, the batter is not permitted to advance if first base is occupied, unless there are already two outs. This is to prevent the catcher from dropping the ball on purpose and setting up a potential double or triple play. The underlying concept is the same as the Infield Fly Rule, to curb defensive shenanigans. Both rules change when there are two outs because then there is no defensive advantage to dropping the ball on purpose. Statistically, such a play still counts as a strikeout for the pitcher; plus either a passed ball charged to the catcher or a wild pitch charged to the pitcher, so if the batter advances safely to first on such a play, it is possible for a pitcher to record four (or more) strikeouts in one inning. Such has happened several dozen times in the history of the major leagues and at least one time in the minor leagues a pitcher has recorded five.

- ↑ Bill Francis, Mickey Owen's Story Part of World Series Lore in Cooperstown National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ↑ Noted exceptions to the dangerous contact rule are found throughout amateur competitions, including youth leagues, high school, and college baseball.

- ↑ Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ↑ Minute Maid Park Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ↑ Green Monster Fenway Fanatics. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ↑ Wrigley Field Information Retrieved April 5, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Block, David. Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game. Bison Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0803262553

- Brinkman, Joe and Charlie Euchner. The Umpire's Handbook, rev. ed. New York: Penguin Books, 1987. ISBN 0828906289

- Elliott, Bob. The Northern Game: Baseball the Canadian Way. Toronto: SportClassic Books, 2005. ISBN 1894963407

- Euchner, Charles. The Last Nine Innings: Inside the Real Game Fans Never See. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, Inc., 2006. ISBN 1402205791

- Evans, Christopher Hodge and William R. Herzog, eds. The Faith of 50 Million: Baseball, Religion, and American Culture. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002. ISBN 0664223052

- Humber, William. Diamonds of the North: A Concise History of Baseball in Canada. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0195410394

- Hye, Allen E. The Great God Baseball: Religion in Modern Baseball Fiction. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2004. ISBN 0865549311

- James, Bill and John Dewan. Bill James Presents the Great American Baseball Stat Book, Edited by Geoff Beckman, et al. New York: Ballantine Books, 1987. ISBN 0345345703

- James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, Revised ed. New York: Free Press, 2003. ISBN 0743227220

- Kearney, Mark. “Baseball's Canadian Roots: Abner Who?” The Beaver, Exploring Canada's History (October-November 1994).

- MacGregor, Jeff. “The New Electoral Sex Symbol: Nascar Dad.” The New York Times, January 18, 2004.

- Mandelbaum, Michael. The Meaning of Sports. New York: PublicAffairs, 2004. ISBN 1586482521

- Novak, Michael. The Joy of Sports: Endzones, Bases, Baskets, Balls, and the Consecration of the American Spirit. New York: Basic Books, 1975. ISBN 0465036791

- Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White. New York: Oxford University Press, (Original, 1970) Reprint ed., 1992. ISBN 0195076370

- Prebish, Charles S. Religion and Sport: The Meeting of Sacred and Profane. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1992. ISBN 0313287295

- Reichler, Joseph L., ed. The Baseball Encyclopedia, New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 10th rev. ed., 1996. ISBN 0028608151

- Ritter, Lawrence and Donald Honig. The Image of Their Greatness: An Illustrated History of Baseball from 1900 to the Present, Updated ed., 1992. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0517587289

- Ritter, Lawrence S. The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It, New York: Harper Paperbacks, New ed., 1992. ISBN 0688112730

- Voigt, David Quentin. Baseball, an Illustrated History. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, (Original 1987) Updated edition, 1995. ISBN 0271014482

External links

All links retrieved September 20, 2023.

- Official Website of Major League Baseball

- Baseball Reference

- Official Website of the British Baseball Federation

- Baseball Basics from MLB.com

- MLB Official Rules

- Stealing Home PBS documentary about baseball and society in Cuba

- The Baseball Catcher Information on Catching

- The Official Site of Minor League Baseball

- Baseball Cards Library of Congress

- The Spalding Base Ball Guides, 1889 to 1939 Library of Congress

- https://www.loc.gov/collections/jackie-robinson-baseball/about-this-collection/ By Popular Demand: Jackie Robinson and Other Baseball Highlights, 1860s-1960s] Library of Congress

- Gerald Early, Cultural Significance of baseball

- National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.