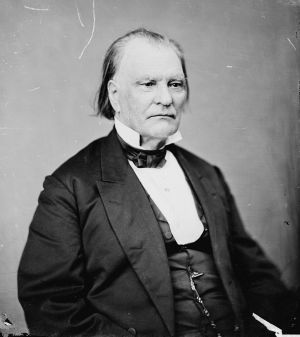

Benjamin F. Wade

Benjamin Franklin Wade (October 27, 1800 – March 2, 1878) was a lawyer and U.S. Senator. In the Senate, he was one of the leaders of a group known as the "Radical Republicans."

Wade gained his reputation as a strong and outspoken opponent of slavery. Known as one of the most radical politicians in America of the era, he also supported women's suffrage, Labor union rights, and equal civil rights for African-Americans. He was highly critical of capitalism, a system which he described as one which "drags the very soul out of a poor man for a pitiful existence."

Known for his blunt direct style, he was described as "a man of violent passions, extreme opinions and narrow views who was surrounded by the worst and most violent elements in the Republican Party." This aspect of his character is believed to have been what saved Andrew Johnson from impeachment; as President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate at the time, Wade would have succeeded Johnson as president of the United States upon Johnson's impeachment. Johnson was acquitted by a single vote.

At the same time, Wade was looked upon by others as one of the bulwarks of the national cause in the darkest hours of the civil war, and was widely admired and respected for his courage, determination, and honesty.

Early life

Benjamin Franklin Wade was born in Feeding Hills, near Springfield, Hampden County, Massachusetts, on October 27, 1800, and was of Puritan ancestry. He was reared on a farm, receiving most of his early education from his mother.

The Wade family moved to Andover, in the Western Reserve of Ohio, in 1821. Benjamin spent two years working on a farm before securing employment as a drover. He worked his way to Philadelphia and finally to Albany, New York. Here he taught school, studied medicine and was a laborer on the Erie Canal.[1]

Benjamin's brother, Edward Wade, also went into politics and was an elected Congressional Representative from Ohio.[2]

Political Life

Wade returned to Ohio in 1825, and studied law at Canfield. He was admitted to the bar in 1827, and began practice at Jefferson, Ashtabula county, where from 1831 to 1837 he was a law partner of Joshua R. Giddings, the prominant anti-slavery leader.

As a member of the Whig Party, Wade was elected to the Ohio State Senate, serving two two-year terms between 1837 and 1842. Between 1847 and 1851, Wade was a district judge in the Ohio court. In 1851 he was elected to a seat in the United States Senate, first as an anti-slavery Whig and later as a Republican. From the beginning, Wade was an uncompromising opponent of slavery, his denunciations of that institution and of the slaveholders bitterly expressed.

In the senate, he associated with such eventually radical Republicans as Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner and became known as a leader of the small anti-slavery minority. He advocated the Homestead bill, the repeal of the controversial Fugitive Slave Act and opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the admission of Kansas to statehood under the Lecompton Constitution of 1858, as well as the purchase of Cuba.[3]

Wade was known as one of the most radical politicians in America at that time, supporting Labor union rights, women's suffrage, and equal civil rights for African-Americans. Wade was highly critical of capitalism and argued that an economic system "which degrades the poor man and elevates the rich, which makes the rich richer and the poor poorer, which drags the very soul out of a poor man for a pitiful existence is wrong."[4]

Known for his blunt, direct style of oratory and his somewhat rough manners, James Garfield warned that Wade was "a man of violent passions, extreme opinions and narrow views who was surrounded by the worst and most violent elements in the Republican Party."

Benjamin Wade was popularly looked upon as one of the bulwarks of the national cause in the darkest hours of the civil war, and by some was widely admired and respected for his courage, determination, and honesty. His candid and powerful eloquence always commanded attention.[5]

Civil War

During the American Civil War, Wade was highly critical of President Lincoln; in a September 1861 letter, he privately wrote that Lincoln's views on slavery "could only come of one born of poor white trash and educated in a slave State." He was especially angry when Lincoln was slow to recruit African-Americans into the armies.

During this time Wade advocated the execution of prominent Southern leaders, the immediate emancipation and arming of slaves, as well as the confiscation of Confederate property.[6]

In July 1861, along with other politicians, Wade witnessed the defeat of the Union Army at the First Battle of Bull Run. There, he was nearly captured by the Confederate Army. After returning to Washington, he was one of those who led the attack on the supposed "incompetence" of the leadership of the Union Army. From 1861 to 1862 he was chairman of the important Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, and in 1862, as chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, was instrumental in abolishing slavery in the Federal Territories.

Wade was also critical of Lincoln's Reconstruction Plan; in 1864, he and Henry Winter Davis sponsored a bill that would run the South, when conquered, their way. The Wade-Davis Bill (which had as its fundamental principle the concept that reconstruction was a legislative, not an executive, problem) mandated that there be a fifty-percent White male Iron-Clad Loyalty Oath, Black male suffrage, and Military Governors that were to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. It passed in the lower chamber on May 4, 1864, by a margin of 73 positive votes to 59 opposing votes; in the upper chamber on July 2, 1864 it passed by a similar percentage of 18 positive to 14 opposing and was brought to Lincoln's desk.

President Lincoln withheld his signature, and on the 8th of July issued a proclamation explaining his course and defining his position, which was that he didn't want to be held to one Reconstruction policy. Soon afterward, on August 5th, Wade and Davis published in the New York Tribune the famous "Wade-Davis Manifesto," a castigating document impugning the "President's honesty of purpose" and attacking his leadership.[7]

Impeachment of Johnson

Andrew Johnson became President of the United States following the assassination of President Lincoln. While he promised severe treatment of the conquered South, Wade supported him, but when he, in actuality, adopted the more lenient policy of his predecessor, Wade became one of his most bitter and uncompromising opponents.

At the beginning of the 40th Congress, Wade became the President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate, which meant that he was the Acting Vice President and next in line for the presidency, since there was no vice president following the assassination.

In February 1868, Johnson notified Congress that he had removed Edwin Stanton as Secretary of War and was replacing him in the interim with Adjutant-General Lorenzo Thomas. This violated the Tenure of Office Act, a law enacted by Congress on March 2, 1867, over Johnson's veto, specifically signed to protect Stanton. The Act removed the President's previous unlimited power to remove any of his Cabinet members at will. (Years later in the case Myers v. United States in 1926, the Supreme Court ruled that such laws were indeed unconstitutional.) Three days after Stanton's removal, the House impeached Johnson for intentionally violating the Tenure of Office Act.

Although most senators reportedly believed that Johnson was guilty of the charges, they did not want the extremely radical Wade to become president. According to John Roy Lynch (R-MS, 1873-76, 1881-82), one of the twenty-two African-Americans elected to Congress from the South during Reconstruction (1861-1901) in his book The Facts of Reconstruction:

It was believed by many at the time that some of the moderate Republican Senators that voted for acquittal of Andrew Johnson did so chiefly on account of their antipathy to the man who would succeed to the presidency in the event of the conviction of the sitting president. This man was Senator Benjamin Wade, of Ohio, President pro tempore of the U. S. Senate who as the law then stood, would have succeeded to the presidency in the event of a vacancy in the office from any cause. Senator Wade was an able man…He was a strong party man. He had no patience with those who claimed to be Radical Republicans and yet refused to abide by the decision of the majority of the party organization (as did Grimes, Johnson, Lincoln, Pratt, and Trumbull)…the sort of active and aggressive man that would be likely to make for himself enemies of men in his own organization who were afraid of his great power and influence, and jealous of him as a political rival. That some of his senatorial Republican associates should feel that the best service they could render their country would be to do all in their power to prevent such a man from being elevated to the Presidency…for while they knew he was an able man, they also knew that, according to his convictions of party duty and party obligations, he firmly believed he who served his party best served his country best…that he would have given the country an able administration is concurrent opinion of those who knew him best.[8]

Final Years

In 1868, then-presidential candidate Ulysses S. Grant was urged by his fellow Republicans to choose Wade as his vice presidential running mate; but he refused, instead choosing another radical, Schuyler Colfax.

After leaving the Senate he resumed his law practice in Jefferson, Ohio, in 1869. He was appointed a government director of the Union Pacific Railroad. In 1871 he became a member of President Ulysses S. Grant's Santo Domingo Commission. He died at Jefferson, Ohio, on March 2, 1878, and is interred in Oakdale Cemetery.

His son, James Franklin Wade, was colonel of the 6th United States cavalry during the Civil War, and attained the rank of major-general in the regular army in 1903, commanding the army in the Philippines in 1903-04.

| Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate |

|

|---|---|

| Langdon • Lee • Langdon • Izard • H Tazewell • Livermore • Bingham • Bradford • Read • Sedgwick • Laurance • Ross • Livermore • Tracy • Howard • Hillhouse • Baldwin • Bradley • Brown • Franklin • Anderson • Smith • Bradley • Milledge • Gregg • Gaillard • Pope • Crawford • Varnum • Gaillard • Barbour • Gaillard • Macon • Smith • L Tazewell • White • Poindexter • Tyler • W R King • Southard • Mangum • Sevier • Atchison • W R King • Atchison • Cass • Bright • Stuart • Bright • Mason • Rusk • Fitzpatrick • Bright • Fitzpatrick • Foot • Clark • Foster • Wade • Anthony • Carpenter • Anthony • Ferry • Thurman • Bayard • Davis • Edmunds • Sherman • Ingalls • Manderson • Ransom • Harris • Frye • (Special: Bacon • Curtis • Gallinger • Brandegee • Lodge) • Clarke • Saulsbury • Cummins • Moses • Pittman • W H King • Harrison • Glass • McKellar • Vandenberg • McKellar • Bridges • George • Hayden • Russell • Ellender • Eastland • Magnuson • Young • Magnuson • Thurmond • Stennis • Byrd • Thurmond • Byrd • Thurmond • Byrd • Stevens • Byrd

Emeritus: Thurmond • Byrd • Stevens |

Notes

- ↑ Benjamin F. Wade, Soylent Communications. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ↑ Wade, Benjamin Franklin, (1800 - 1878), Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ↑ Benjamin F. Wade, Soylent Communications. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ↑ Benjamin Wade, 1800 - 1878, The Latin Library at Ad Fontes Academy. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ↑ Benjamin Wade, 1800 - 1878, The Latin Library at Ad Fontes Academy. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ↑ Benjamin F. Wade, Soylent Communications. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ↑ Benjamin F. Wade, Soylent Communications. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ↑ John Roy Lynch, The facts of reconstruction. The American Negro; his history and literature (New York: Arno Press, 1968).

References and further reading

- Bupp, Reno W. The senatorial career of Benjamin F. Wade to 1861. 1939. OCLC 61718019

- Lynch, John Roy. 1913. The facts of reconstruction. The American Negro; his history and literature. New York: Arno Press, Reprinted 1968.

- Seward, William Henry, Stephen Arnold Douglas, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Everett, Truman Smith, and George Edmund Badger. Speeches in Congress on The compromises of 1850 and Nebraska and Kansas. Washington, 1854. OCLC 4759295

- Wade, B.F. The papers of Benjamin F. Wade. 1832-1878. Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1938. OCLC 30501168

- Williams, Thomas Harry. Benjamin F. Wade 1864-1869. 1932. OCLC 57655904

External links

All links retrieved September 28, 2023.

- WADE, Benjamin Franklin, (1800 - 1878) Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Benjamin F. Wade NNDB-Soylent Communications

- Brainy Quote Benjamin F. Wade

- Benjamin Wade, 1800 - 1878 The Latin Library at Ad Fontes Academy

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.