Berber

| Berbers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. - 36 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Berber languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Islam (mostly Sunni), Christianity, Judaism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Egyptians, possibly Iberians |

The Berbers (Imazighen, singular Amazigh) are an ethnic group indigenous to Northwest Africa, speaking the Berber languages of the Afroasiatic family. Originally, Berber was a generic name given by the Romans to numerous heterogeneous ethnic groups that shared similar cultural, political, and economic practices. It was not a term originated by the group itself.

Despite the appearance of two significant Berber dynasties, the Almoravids (eleventh century) and the Almohads, (twelfth century) the Berber tribes could never unite long enough to rid themselves of the numerous conquerors who invaded their lands. As a result, Berber history can only be followed as the history of individual tribes. Some of these ancient tribes were Gaetulians, Maures, Massyli, Garamantes, Augilae, and Nasamones.

While Berbers are stereotyped as nomads, and indeed some tribes are, the majority are typically farmers. It is difficult to estimate the number of Berbers in the world today, because many do not define themselves as Berber. However the Berber language is spoken by an estimated 14 to 25 million people.

Origin

The Berbers have lived in North Africa for thousands of years and their presence has been recorded as early as 3000 B.C.E. Greeks, Romans, and ancient Egyptians have indicated the presence of Berbers in their records.[1] The Maghreb region in northwestern Africa is believed to have been inhabited by Berbers from at least 10,000 B.C.E.[2] There is no complete certitude about the origin of the Berbers; however, various disciplines shed light on the matter.

Genetic evidence

In general, genetic evidence appears to indicate that most northwest Africans (whether they consider themselves Berber or Arab) are predominantly of Berber origin, and that populations ancestral to the Berbers have been in the area since the Upper Paleolithic era. The genetically predominant ancestors of the Berbers appear to have come from East Africa, the Middle East, or both—but the details of this remain unclear. However, significant proportions of both the Berber and Arabized Berber gene pools derive from more recent human migration of various Italic, Semitic, Germanic, and sub-Saharan African peoples, all of whom have left their genetic footprints in the region.

Archaeological

The Neolithic Capsian culture appeared in North Africa around 9,500 B.C.E. and lasted until possibly 2700 B.C.E. Linguists and population geneticists alike have identified this culture as a probable period for the spread of an Afro-Asiatic language (ancestral to the modern Berber languages) to the area. The origins of the Capsian culture, however, are archeologically unclear. Some have regarded this culture's population as simply a continuation of the earlier Mesolithic Ibero-Maurusian culture, which appeared around 22,000 B.C.E., while others argue for a population change; the former view seems to be supported by dental evidence. [3]

Name

Historically, it is not clear how the name "Berber" evolved, although it is supposed to be from the word "barbarian," applied by Romans to many peoples. The variation is a French one when spelled Berbere and English when spelled "Berber."

Due to the fact that the Berbers were called "El-Barbar" by the Arabs, it is very probable that the modern European languages adopted it from the Arabic language. The Arabs didn't use the name "El-Barbar" as a negative, not being aware of the origin of that name; they supposedly created some myths or stories about the name.

The medieval Tunisian historian Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), recounting the oral traditions prevalent in his day, sets down two popular opinions as to the origin of the Berbers: according to one opinion, they are descended from Canaan, son of Ham, and have for ancestors Berber, son of Temla, son of Mazîgh, son of Canaan, son of Ham, a son of Noah; alternatively, Abou-Bekr Mohammed es-Souli (947 C.E.) held that they are descended from Berber, the son of Keloudjm (Casluhim), the son of Mesraim, the son of Ham.[4]

The fact that the name "Berber" is a strange name to the Berbers leads to confusion. Some sources claim that the Berbers are several ethnic groups who are not related to each other. That is not accurate, because the Berbers refer to themselves as Imazighen (singular Amazigh) in Morocco, as well as in Libya, Egypt (Siwa) and other areas of North Africa, and speak the Berber language Tamazight.[5]

Not only is the origin of the name "Berber" unclear, but also is the name "Amazigh." The most common explanation is that the name goes back to the Egyptian period when the Ancient Egyptians mentioned an ancient Libyan tribe called Meshwesh. The Meshwesh are supposed by some scholars to be the same ancient Libyan tribe that was mentioned as "Maxyans" by the Greek Historian Herodotus.

Both names, "Amazigh" and "Berber," are relatively recent names in historical sources, since the name "Berber" appeared first in Arab-Islamic sources, and the name "Amazigh" was never used in ancient sources. It is no less important to keep in mind that the Berbers were known by various names in different periods.

The first reference to the Ancient Berbers goes back to a very ancient Egyptian period. They were mentioned in the pre-dynastic period, on the so-called "Stele of Tehenou" which is still preserved in the Cairo museum in Egypt. That tablet is considered to be the oldest source wherein the Berbers have been mentioned.

The second source is known as The Stele of King Narmer. This tablet is newer than the first source, and it depicted the Tehenou as captives.

The second oldest name is Tamahou. This name was mentioned for the first time in the period of the first king of the "Sixth Dynasty" and was referred to in other sources after that period. According to Oric Bates, those people were white-skinned, with blond hair and blue eyes.

In the Greek period the Berbers were mainly known as "The Libyans" and their lands as "Libya" that extended from modern Morocco to the western borders of ancient Egypt. Modern Egypt contains Siwa, part of historical Libya, where they still speaks the Berber language.

During the Roman period, the Berbers would become known as Numidians, Maures, and Getulians, according to their tribes or kingdoms. The Numidians founded complicated and organized tribes, and thereafter began to build a stronger kingdom. Most scholars believe that "Alyamas" was the first king of the Numidian kingdom. Massinissa was the most famous Numidian king, who made Numidia a strong and civilized kingdom.

History

The Berbers have lived in North Africa between western Egypt and the Atlantic Ocean for as far back as records of the area go. The earliest inhabitants of the region are found on the rock art across the Sahara. References to them also occur frequently in Ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sources. Berber groups are first mentioned in writing by the ancient Egyptians during the Predynastic Period, and during the New Kingdom the Egyptians later fought against the Meshwesh and Lebu (Libyans) tribes on their western borders. Many Egyptologists think that from about 945 B.C.E. the Egyptians were ruled by Meshwesh immigrants who founded the Twenty-second Dynasty of Egypt under Shoshenq I, beginning a long period of Berber rule in Egypt, although others posit different origins for these dynasties, including Nubian. They long remained the main population of the Western Desert—the Byzantine chroniclers often complained of the Mazikes (Amazigh) raiding outlying monasteries there.

For many centuries the Berbers inhabited the coast of North Africa from Egypt to the Atlantic Ocean. Over time, the coastal regions of North Africa saw a long parade of invaders and colonists including Saharans, Phoenicians (who founded Carthage), Greeks (mainly in Libya), Romans, Vandals and Alans, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottomans, and the French and Spanish. Most, if not all, of these invaders have left some imprint upon the modern Berbers as have slaves brought from throughout Europe (some estimates place the number of Europeans brought to North Africa during the Ottoman period as high as 1.25 million). [6] Interactions with neighboring Sudanic empires, sub-Saharan Africans, and nomads from East Africa also left vast impressions upon the Berber peoples.

In historical times, the Berbers expanded south into the Sahara, displacing earlier populations such as the Azer and Bafour, and have in turn been mainly culturally assimilated in much of North Africa by Arabs, particularly following the incursion of the Banu Hilal in the eleventh century.

The areas of North Africa which retained the Berber language and traditions have, in general, been those least exposed to foreign rule—in particular, the highlands of Kabylie and Morocco, most of which even in Roman and Ottoman times remained largely independent, and where the Phoenicians never penetrated beyond the coast. However, even these areas have been affected by some of the many invasions of North Africa, most recently including the French. Another major source of foreign influence, particularly in the Sahara, was the Trans-Atlantic Slave trade route from West Africa, operated in part by the European commercial powers.

Berbers and the Islamic conquest

Unlike the conquests of previous religions and cultures, the coming of Islam, which was spread by Arabs, was to have pervasive and long-lasting effects on the Maghreb. The new faith, in its various forms, would penetrate nearly all segments of society, bringing with it armies, learned men, and fervent mystics, and in large part replacing tribal practices and loyalties with new social norms and political idioms.

Nonetheless, the Islamization and Arabization of the region were complicated and lengthy processes. Whereas nomadic Berbers were quick to convert and assist the Arab conquerors, not until the twelfth century, under the Almohad Dynasty, did the Christian and Jewish communities become totally marginalized.

The Berbers and their languages

The Berber languages are a group of closely related languages belonging to the Afro-Asiatic languages phylum. There is a strong movement among Berbers to unify the closely related northern Berber languages into a single standard, Tamazight, which is a frequently used generic name for all Berber languages. There are around three hundred local dialects among the scattered Berber populations.

The exact population of Berber speakers is hard to ascertain, since most Maghreb countries do not record language data in their census data. Early colonial censuses may provide documented figures for some countries; however, those statistics are no longer a reliable measure. It is estimated that there are between 14 and 25 million speakers of Berber languages in North Africa, principally concentrated in Morocco and Algeria, with smaller communities as far east as Egypt and as far south as Burkina Faso.

Among the Berber languages are Tarifit or Riffi in northern Morocco, Kabyle in Algeria and Tashelhiyt in central Morocco. Tamazight has been a written language, on and off, for almost 3,000 years; however, this tradition has been frequently disrupted by various invasions. It was first written in the Tifinagh alphabet, still used by the Tuareg; the oldest dated inscription is from about 200 B.C.E. Later, between about 1000 C.E. and 1500 C.E., it was written in the Arabic alphabet, particularly by the Shilha of Morocco; since the beginning of the twentieth century, it has often been written in the Latin alphabet, especially among the Kabyle. A variant of the Tifinagh alphabet was recently made official in Morocco, while the Latin alphabet is official in Algeria, Mali, and Niger; however, both Tifinagh and Arabic are still widely used in Mali and Niger, while Latin and Arabic are still widely used in Morocco.

After independence, all the Maghreb countries, to varying degrees, pursued a policy of "Arabization," aimed primarily at displacing French from its colonial position as the dominant language of education and literacy. But under this policy the use of both Berber languages and Maghrebi Arabic have been suppressed as well. This state of affairs has been contested by Berbers in Morocco and Algeria, especially Kabylie, and is now being addressed in both countries by introducing Berber language education and by recognizing Berber as a "national language," though not necessarily an official one. No such measures have been taken in the other Maghreb countries, whose Berber populations are much smaller. In Mali and Niger, there are a few schools that teach partially in the Tamasheq language.

Religions and beliefs

Berbers are mainly Sunni Muslim, but there are many traditional practices found among them. Since Berbers typically outnumber Arabs in rural areas, traditional practices tend to predominate there. The Berbers converted to Islam slowly, over the course of centuries, and was not dominant until the sixteenth century. The result is that within Berber Islam are preserved traces of former religious practices, making it a somewhat atypical sect.[7]

Most belonging to the Maliki madhhab, while the Mozabites, Djerbans, and Nafusis of the northern Sahara are Ibadi Muslim. Sufi tariqas are common in the western areas, but rarer in the east; marabout cults were traditionally important in most areas.

Before their conversion to Islam, some Berber groups had converted to Christianity (often Donatist) or Judaism, while others had continued to practice traditional polytheism. Under the influence of Islamic culture, some syncretic religions briefly emerged, as among the Berghouata, only to be replaced by Islam.

Berber Jews

Berber Jews inhabit the region coinciding with the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. Between 1950 and 1960 most immigrated to Israel. Some 2,000 of them, all elderly, still speak Judeo-Berber. [8] Their garb and culture was similar to neighboring Berber Muslims.

It would be difficult to determine whether these Jewish Berber tribes were originally of Jewish descent and had become assimilated with the Berbers in language, habits, mode of life—in short, in everything except religion—or whether they were native Berbers who in the course of centuries had been converted by Jewish settlers. It is the second option which is considered as more likely by researchers such as André Goldenberg or Simon Levy.

The question on the origins of the Berber Jews is also further complicated by the likelihood of intermarriage. However this may have been, they at any rate shared much with their non-Jewish brethren in the Berber territory, and, like them, fought against the Arab conquerors.

Modern-day Berbers

Demographics

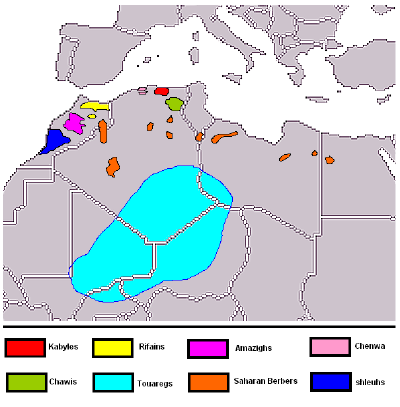

The Berbers live mainly in Morocco (between 35 percent-60 percent of the population) and in Algeria (about 15 to 33 percent of the population), as well as Libya and Tunisia, though exact statistics are unavailable. Most North Africans who consider themselves Arab also have significant Berber ancestry.[9] Prominent Berber groups include the Kabyles of northern Algeria, who number approximately four million and have kept, to a large degree, their original language and culture; and the Chleuh (francophone plural of Arabic "Shalh") and Tashelhiyt of south Morocco, numbering about eight million. Other groups include the Riffians of north Morocco, the Chaouia of Algeria, and the Tuareg of the Sahara. There are approximately three million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians and the Kabyles in the Netherlands and France. Some proportion of the inhabitants of the Canary Islands are descended from the aboriginal Guanches—usually considered to have been Berber—among whom a few Canary Islander customs, such as the eating of gofio, originated.

Relations with Europe

As with most people in the world today, Berbers easily blend in with other people. However, there are differences due to North Africa's history, known as the Barbary Coast. During the time of the Barbary pirates, slaves and war prisoners from Europe were transported and sold into North Africa. Estimates place possibly one million Europeans arriving in Africa this way, bringing with them green and blue eyes and blond and red hair. As intermarriage took place with the resident North Africans, these features became incorporated into today's Berber population.

Although stereotyped in the West as nomads, most Berbers were in fact traditionally farmers, living in the mountains relatively close to the Mediterranean coast, or oasis dwellers; the Tuareg and Zenaga of the southern Sahara, however, were nomadic. Some groups, such as the Chaouis, practiced transhumance.

Today Berbers often live in the mountains and in smaller settlements throughout the North African terrain. Of the region's major cities, only Marrakech has a population with a strong Berber identity. During the days of the Arab conquest, the invaders took control of the cities, for the most part ignoring the rural areas. The Berber peoples had several choices; living in the mountains, resisting Arab dominance, or moving into the Arab community, where Arab language and culture were dominant. Many chose a mountain life, where their descendents remain today.

Similar to the situation in many Western societies such as Native peoples in the U.S., Aboriginals in Australia, and Lapps in Norway, the Berbers were considered to be second class citizens until the middle of the twentieth century. In some areas of northern Africa, the Berber people continue to be looked upon as 'illiterate peasants' dressed in traditional garments.

As with many other indigenous peoples throughout the world, the Berbers had begun to rise up in the latter years of the twentieth century, speaking out against the undervaluation of their culture and identity. Major points of protest have been the absence of a written language and the lack of political influence. This has been most obvious in Algeria, where the situation had been so tense during the 1990s, that foreign commentators had speculated about the prospects for a civil war and a partition of the country.[7]

Today the Berbers of Algeria are the most educated group, and many hold leading positions in society. This is due in part to the actions of the French during the colonial period, who attempted to weaken the Arab aspects of Algerian culture by giving preference to Berbers in education and administration. This has resulted in Algeria having one of the most influential Berber cultures of all countries with a Berber population. The Berber language is used as an everyday language in that country, though French is the administrative language.

Political tensions have arisen between some Berber groups, especially the Kabyle, and North African governments over the past few decades, partly over linguistic and cultural issues; for instance, in Morocco, giving children Berber names was banned.

Notes

- ↑ History of the Berbers and North Africa Facts and Details, September 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ↑ Hsain Ilahiane, Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen) (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017, ISBN 978-1442281813).

- ↑ J.D. Irish, The Iberomaurusian enigma: north African progenitor or dead end? Journal of Human Evolution 39(4) (October 2000):393-410. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ↑ Ibn Khaldun, Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique septentrionale (Wentworth Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0341079767).

- ↑ Peter Prengaman, Morocco's Berbers Battle to Keep From Losing Their Culture, San Francisco Chronicle, March 16, 2001. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ↑ Jeff Grabmeier, "When Europeans were Slaves: Research Suggests White Slavery was much more Common than Previously Believed." In Robert Davis, Christian Slaves; Muslim Masters (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004, ISBN 978-1403945518).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Jimmy Joe, Berber People: The Natives of North Africa Timeless Myth. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ↑ Raymond G. Gordon, Jr. Judeo-Berber: A language of Israel Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ↑ Elena Bosch, Francesc Calafell, David Comas, Peter J. Oefner, Peter A. Underhill, and Jaume Bertranpetit, High-Resolution Analysis of Human Y-Chromosome Variation Shows a Sharp Discontinuity and Limited Gene Flow between Northwestern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula The American Society of Human Genetics 68(4) (April 2001): 1019–1029. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brett, Michael, and Elizabeth Fentress. The Berbers. Oxford, England: & Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0631168524

- Briggs, Lloyd Cabot. The Stone Age Races of Northwest Africa. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum, 1955. ASIN B000M4HLFG

- Celenko, Theodore. Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, IN: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1996. ISBN 0936260645

- Davis, Robert. Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 978-1403945518

- Ehret, Christopher. The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 2002, ISBN 0813920841

- Hachid, Malika. Les premiers Berbères: entre Méditerranée, Tassili et Nil. Edisud, 2001. ISBN 2744902276

- Hagan, Helene E., The Shining Ones: an Etymological Essay on the Amazigh Roots of Ancient Egyptian Civilisation. XLibris, US, 2001, ISBN 1401024122

- Hagan, Helene E. Tuareg Jewelry: Traditional Patterns and Symbols. XLibris, 2006. ASIN B0793SVGWK

- Hiernaux, Jean. The People of Africa (People of the world series). New York, NY: Scribner, 1975. ISBN 0684140403

- Ilahiane, Hsain. Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017. ISBN 978-1442281813

- Khaldun, Ibn. Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique septentrionale. Wentworth Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0341079767

- Osborn, Henry Fairfield. Men of the old stone age, their environment, life and art. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1171826361

- Silverstein, Paul A. Algeria in France: Transpolitics, Race, and Nation. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004. ISBN 0253344514

External links

All links retrieved September 28, 2023.

- Amar Almasude, The New Mass Media and the Shaping of Amazigh Identity Revitalizing Indigenous Languages.

- Jose Barrios Garca, Sept 1997 Number Systems and Calendars of the Berber Populations of Grand Canary and Tenerife Archaeoastronomy & Ethnoastronomy News.

- Amazigh World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples

- Berbers World History Encyclopedia

- Morocco: Brief history of the Berbers including their origins and geographic location Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada November 16, 2000.

- The Amazigh Cultural Renaissance by Mohamed Chtatou, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, January 18, 2019.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.