Blackfoot

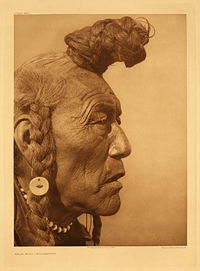

| Blackfoot |

|---|

| Bear Bull |

| Total population |

| 32,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Canada (Alberta) United States (Montana) |

| Languages |

| English, Blackfoot |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| other Algonquian peoples |

The Blackfoot confederacy of Alberta in Canada and Montana in the United States was created from closely related, Algonkian-speaking tribes: the Piegan, the Kainai (Blood), and the Siksika (from which the word Blackfoot derived). They were a powerful nation that covered the Great Plains of the North American continent. They were accomplished hunters and traders with posts that extended to the east coast and Mexico.

The Blackfoot were renowned warriors and stood against white encroachment for a quarter of a century. At the end of the nineteenth century, they became nearly extinct due to disease and demise of the buffalo. The survivors were forced onto reservations. This nation once covered the vast region of central Canada and the United States uniting many tribes of people into a common bond. They lived for thousands of years in close relationship to the natural environment. In many ways, it can be said that they were masters of living with the creation. The near extinction of this nation after the arrival of European settlers and traders was a great loss to humanity and, as with all cases of genocide, there is need for restoration by acknowledgment and healing of the pain of this loss. It can only be hoped that in the future the Blackfeet will be able to bring great wisdom back to the center of humanity's treasures.

Overview

The Blackfoot Confederacy is the collective name of three First Nations in Alberta and one Native American tribe in Montana.

The Blackfoot Confederacy consists of the North Piegan (Aapatohsipiikanii), the South Piegan (Aamsskaapipiikanii), the Kainai Nation (Blood), and the Siksika Nation ("Blackfoot") or more correctly Siksikawa ("Blackfoot people"). The South Piegan are located in Montana, and the other three are located in Alberta. Together they call themselves the Niitsitapii (the "Real People"). These groups shared a common language and culture, had treaties of mutual defense, and freely intermarried.

It is also speculated that "Blackfoot Cherokee" refers to a band of Cherokee that had black ancestry, most likely from the adoption of escaped slaves into their society. This band of Cherokee, however, have no connection to the Blackfoot nations.

History

Archaeologists have identified evidence of early native ancestors who arrived after the Pleistocene Glacial period approximately 11,000 years ago. Some evidence of the presence of humans prior to this time has raised debate among some indigenous groups and scientists regarding the actual first ancestor of the Americas. Much evidence of permanent residents has been found that dates between 3,000 to 5,000 years ago. These natives spoke the Algonkian language. The Blackfoot Nation comprises the lineages from these early people.[1]

The confederation in the United States and Canada was made up of three groups: The Northern Blackfoot or Siksika, the Kainai or Blood, and the Piegan. This structure was not an authoritative political system as such but brought the groups together for ceremonial gatherings and summer hunting. Buffalo were often hunted in drives that sent stampeding herds over steep cliffs killing them in large numbers.[2]

The Blackfoot, like other Plains Indians of North America, lived without horses for thousands of years while still maintaining a hunter-gatherer way of life. Up until around 1730, the Blackfoot traveled by foot and used dogs to carry and pull some of their goods. They had not seen horses in their previous lands, but were introduced to them on the Plains, as other tribes, such as the Shoshone, had already adopted their use.[3] They saw the advantages of horses and wanted some. The Blackfoot called the horses ponokamita (elk dogs).[4] The horses could carry much more weight than dogs and moved at a greater speed. They could be ridden for hunting and travel.[5]

Horses revolutionized life on the Great Plains and soon came to be regarded as a measure of wealth. Warriors regularly raided other tribes for their best horses. Horses were generally used as universal standards of barter. Shamans were paid for cures and healing with horses. Dreamers who designed shields or war bonnets were also paid in horses.[6] The men gave horses to those who were owed gifts as well as to the needy. An individual’s wealth rose with the number of horses accumulated, but a man did not keep an abundance of them. The individual’s prestige and status was judged by the number of horses that he could give away. For the Indians who lived on the Plains, the principal value of property was to share it with others.[7]

The first contact of the Blackfoot in Southern Alberta with white traders occurred in the late 1700s. Before this, other native groups brought trade items inland and also encroached on Blackfoot territory with the advantage of European rifles and technology. The first white people to attempt to make contact were Americans. They were strongly resisted. In 1831, a peace agreement was formed with an American fur trading company at Fort Piegan in Missouri. In the next few decades after this, American traders brought smallpox disease. In 1870, the Marias Massacre occurred. American troops killed 200 Piegan women, children, and elderly despite the fact that the camp was friendly. The Blackfoot population was reduced from around 11,000 to 6,000 people in a fifty year period.[1]

Treaties

"Treaty 7" was a peaceful treaty signed in 1877 between the Canadian government and the Blackfoot Confederacy including the Piegan, Blood, Sarcee, Bearspaw, Chiniki, and Wesley/Goodstoney. The impetus for the treaty was driven by the desire of the Canadian government to assure land rights before the construction of a transcontinental railway. The signing occurred at Blackfoot Crossing on the Siksika Reserve east of Calgary. A historical park has been constructed as a cultural museum in the same place as Chief Crowfoot signed the document.[8]

In 1855, the Niitsitapi chief Lame Bull made a peace treaty with the United States government. The Lame Bull Treaty promised the Niitsitapi $20,000 annually in goods and services in exchange for their moving onto a reservation.[9] When the Blackfeet Reservation was first established in 1855 by this treaty, it included the eastern area of the Glacier National Park up to the Continental Divide.[10] To the Blackfeet, the mountains of this area, especially Chief Mountain and the region in the southeast at Two Medicine, were considered the "Backbone of the World" and were frequented during vision quests.[11] In 1895, Chief White Calf of the Blackfeet authorized the sale of the mountain area, some 800,000 acres (3,200 km²), to the U.S. government for $1.5 million with the understanding that they would maintain usage rights to the land for hunting as long as the ceded stripe will be public land of the United States.[12] This established the current boundary between Glacier National Park and the reservation.

Blackfoot culture

The Blackfoot were fiercely independent and very successful warriors whose territory stretched from the North Saskatchewan River along what is now Edmonton, Alberta in Canada, to the Yellowstone River of Montana, and from the Rocky Mountains and along the Saskatchewan river past Regina.

The basic social unit of the Blackfoot, above the family, was the band, varying from about 10 to 30 lodges, about 80 to 240 people. This size of group was large enough to defend against attack and to undertake small communal hunts, but was also small enough for flexibility. Each band consisted of a respected leader, possibly his brothers and parents, and others who need not be related. Since the band was defined by place of residence, rather than by kinship, a person was free to leave one band and join another, which tended to ameliorate leadership disputes. As well, should a band fall upon hard times, its members could split up and join other bands. In practice, bands were constantly forming and breaking up. The system maximized flexibility and was an ideal organization for a hunting people on the Northwestern Plains.

Blackfoot people were nomadic, following the American buffalo herds. Survival required their being in the proper place at the proper time. For almost half the year in the long northern winter, the Blackfoot people lived in their winter camps along a wooded river valley perhaps a day's march apart, not moving camp unless food for the people and horses or firewood became depleted. Where there was adequate wood and game resources, some bands might camp together. During this part of the year, bison wintered in wooded areas where they were partially sheltered from storms and snow, which hampered their movements, making them easier prey. In spring the bison moved out onto the grasslands to forage on new spring growth. The Blackfoot did not follow immediately, for fear of late blizzards, but eventually resources such as dried food or game became depleted, and the bands would split up and begin to hunt the bison, also called the buffalo.

In mid-summer, when the Saskatoon berries ripened, the people regrouped for their major tribal ceremony, the Sun Dance. This was the only time of year when the entire tribe would assemble, and served the social purpose of reinforcing the bonds between the various groups, and re-identifying the individuals with the tribe. Communal buffalo hunts provided food and offerings of the bulls' tongues (a delicacy) for the ceremonies. After the Sun Dance, the people again separated to follow the buffalo.

In the fall, the people would gradually shift to their wintering areas and prepare the buffalo jumps and pounds. Several groups of people might join together at particularly good sites. As the buffalo were naturally driven into the area by the gradual late summer drying off of the open grasslands, the Blackfoot would carry out great communal buffalo kills, and prepare dry meat and pemmican to last them through winter, and other times when hunting was poor. At the end of the fall, the Blackfoot would move to their winter camps.

The Blackfoot maintained this traditional way of life based on hunting buffalo, until the near extinction of the great animal by 1881, an effect of the European colonization of the Americas, forced them to adapt their ways of life. In the United States, they were restricted to land assigned in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 and were later given a distinct reservation in the Sweetgrass Hills Treaty of 1887. In 1877, the Canadian Blackfoot signed Treaty 7, and settled on the reservation in southern Alberta.

This began a period of great struggle and economic hardship, as the Blackfoot had to try to adapt to a completely new way of life, as well as suffer exposure to many diseases their people had not previously encountered. Eventually, they established a viable economy based on farming, ranching, and light industry, and their population has increased to about 16,000 in Canada and 15,000 in the U.S. With their new economic stability, the Blackfoot have been free to adapt their culture and traditions to their new circumstances, renewing their connection to their ancient roots.

Religion

In Blackfoot religion, the Old Man (Na'pi) was the Creator (God) of the ancient Blackfoot tribes. The word correlates with the color white and to the light of early morning sunrise. The character of the Old Man was a constant theme of Blackfoot lore. He depicted a full spectrum of human attributes that included themes of strength, weakness, folly, malice, and so forth. It was said that he went away to the West (or East) over the mountains but told the people he would return some day. This has been interpreted by some tribal members as the return of the buffalo to the people.

The Sun replaced the Old Man in the Blackfoot religious system. The Moon was the Sun's wife. The character of the Sun was benevolent, wise, and generous. The tongue of the buffalo was sacred to the Sun as was the suffering of the Sun Dancers in the Medicine Lodge. There were a number of minor deities. Animals, birds, insects, and plants were important as guides and helpers.

There was a strong belief in the existence of spirits. The spirits of those that lived wicked lives were separated from good spirits and were thought to remain close to the place where they died. Sometimes these wicked spirits wished to do ill out of revenge or jealousy and could bother people. It was thought that spirits sometimes dwell in animals. Owls are thought to be inhabited by the spirits of medicine men.[13]

In the the twenty-first century, the old traditions of religious practice are still alive. The Sun Dance is maintained, as are medicine bundles, sweat lodges, and guardian spirit traditions. There is an annual Medicine Lodge ceremony and Sun Dance in July.

Increased interest in the indigenous knowledge of some Native American societies emerged in the late 1900s and has brought together people from many professions, cultures, and religious belief systems. The Sun Dance ceremony, the mystery renewal of Turtle Island (the North American continent), and festivals celebrating wild things have brought together anthropologists, scientists, poets, writers, spiritual seekers, and more, resulting in an increase in books, music, art, and poetry about the ancient ways. One example of this is the book, Blackfoot Physics, based on the experiences of a theoretical physicist F. David Peat in the 1980s. He wrote, "within the Indigenous world the act of coming to know something involves a personal transformation. The knower and the known are indissolubly linked and changed in a fundamental way."[14]

The importance of animals

- Buffalo (American bison)

The bison was highly revered and was often regarded as a Medicine (helper) Animal. Buffalo skulls were placed outside the sweat lodges of the Medicine Lodge. The buffalo tongue was the Sun's favorite food. The white buffalo was regarded as sacred.

- Wolf

The Blackfoot hunted bison before horses were introduced. Ancient legends have been passed down that tell of ancestors using the robes of wolves or coyotes to stalk herds:

Instead of collecting data on bison, Blackfoot performed as wolves. They tried to look like wolves and move like wolves. They became wolves in ceremonies at home camp, and in presence of bison herds … By becoming brothers to the wolf, Blackfoot could quickly discover effective means of manipulating the bison … through performances that could easily be mistaken for purely "cultural activities".ref>Russell Barsh, "Driving Bison and Blackfoot Science." Human Ecology 31 (2003).</ref>

- Horse

Before the introduction of horses, the Blackfoot had a "Pedestrian Culture" economy. However, no European had met the Blackfoot before they had acquired horses, so earlier periods can only be understood through inference and anthropology. There were myths about how the horse came to the Blackfoot that were passed down through generations from elders. One such Piegan myth, for example, was titled, "How Morning Star Made the First Horse," which opens, "Until this time, the people had only dogs."[15]

The historic period called the "Horse Culture Period" was from approximately 1540 - 1880. The last date corresponds roughly with the extermination of the buffalo in the Great Plains. Blackfoot social status respected the right of individual ownership. "A man owning 40 or more horses was considered to be wealthy" [16]

- Butterfly

The butterfly and moth were common figures in Blackfoot artwork, myths, and songs. It was believed that butterflies were carriers of dreams. It was a custom for mothers to embroider a butterfly on buckskin strips to place in their baby's hair. They would then sing a lullaby calling the butterfly to bring the child sleep.[17]

Contemporary Blackfoot

Today, many of the Blackfoot live on reserves in Canada. In Canada, the Blackfoot Tribe has changed its name to Siksika Nation, and the Piegans are called both the Piegan Nation and Pikuni Nation. The Northern Piegan make clothing and moccasins, and the Kainai operate a shopping center and factory.[9]

About 8,500 Blackfeet live on the Montana reservation of 1,500,000 acres (6,100 km²). Unemployment is a challenging problem on the Blackfoot Reservations. Many people work as farmers, but there are not enough other jobs nearby. To find work, many Blackfoot have relocated from the reservation to towns and cities. Some companies pay the Blackfoot for leasing use of oil, natural gas, and other resources on the land. They operate businesses such as the Blackfoot Writing Company, a pen and pencil factory, which opened in 1972, but it closed in the late 1990s.

In 1982, the tribe received a settlement of $29 million as compensation for mistakes in federal accounting practices. On March 15, 1999, the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council approved the establishment of Siyeh Corporation in Browning, Montana. The corporation's purpose is to generate business development, create jobs, produce revenue, and advance the economic self-sufficiency of the Tribe by managing its tribal enterprises. Siyeh manages businesses including an Indian gaming casino, Glacier Peaks Casino in Browning, as well as the Blackfeet Heritage Center and Art Gallery.

The Blackfoot continue to make advancements in education. In 1974, they opened the Blackfeet Community College in Browning, Montana. The school also serves as tribal headquarters. As of 1979, the Montana state government requires all public school teachers on or near the reservation to have a background in American Indian studies. In 1989, the Siksika tribe in Canada completed a high school to go along with its elementary school.[9] Language classes are in place to keep their language alive. In Canada, the Red Crow College offers courses on the Siksika Reserve. Blackfoot students increasingly finding new means of employment based on their cultural ties and educational opportunities.[18]

Blackfoot Crossing Memorial Park

The Siksika nation has created a memorial park at the the site of the signing of Treaty No. 7 in Alberta, Canada. It is called the Blackfoot Crossing Memorial Park, and represents a revival of tribal pride in their history, culture, and language that has grown in strength into the twenty-first century. In the part, storytelling and oral tradition will be used to communicate the culture of the North Plains Indians to Siksika members and visitors.[8] There will also be traditional dances, language classes, costumes, teepee circles, and ceremonial activities held there. The symbol of the buffalo was registered as the Siksika Coat of Arms with the Heraldic Authority of Canada in 1992 (the first such registry of a First Nation in Canada).

Continuing traditions

The Blackfoot continue many cultural traditions of the past and hope to extend their ancestors' traditions to their children. They want to teach their children the Pikuni language as well as other traditional knowledge. In the early twentieth century, a white woman named Frances Densmore helped the Blackfoot record their language. During the 1950s and 1960s, few Blackfoot spoke the Pikuni language. In order to save their language, the Blackfoot Council asked elders who still knew the language to teach it. The elders had agreed and succeeded in reviving the language, so today the children can learn Pikuni at school or at home. In 1994, the Blackfoot Council accepted Pikuni as the official language.[9]

The people also revived the Black Lodge Society, responsible for protecting songs and dances of the Blackfoot. They continue to announce the coming of spring by opening five medicine bundles, one at every sound of thunder during the spring.[9] The Sun Dance, which was illegal from the 1890s-1934, has been practiced again for years. Since 1934, the Blackfoot have practiced it every summer. The event lasts eight days—time filled with prayers, dancing, singing, and offerings to honor the Creator. It provides an opportunity for the Blackfoot to get together and share views and ideas with each other, while celebrating their culture's most sacred ceremonies.[9]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Native History Indian Tribes of Alberta. (Calgary: Glenbow Museum, 1979). Retrieved March 23, 2007

- ↑ Marlene M. Martin, Society-BLACKFOOT. Retrieved on March 23, 2007.

- ↑ George Bird Grinnell, "Early Blackfoot History," American Anthropologist 5(2) (Apr., 1892): 153-164.

- ↑ Stuart J. Baldwin, "Blackfoot Neologisms," International Journal of American Linguistics 60(1) (Jan., 1994): 69-72.

- ↑ David S. Murdoch, North American Indian (New York, NY: DK Publishing, 2005, ISBN 978-0132133616).

- ↑ Colin Taylor, What Do We Know About The Plains Indians? (New York, NY: Peter Bedrick Books, 1993, ISBN 978-0872262614).

- ↑ Royal B. Hassrick, The Colorful Story of North American Indians (New York, NY: Book Sales, Inc., 1975, ISBN 978-0706403602), 77.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Blackfoot Crossing, Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park (2005). Retrieved on March 20, 2007.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Karen Bush Gibson, The Blackfeet: People of the Dark Moccasins (Mankato, MN: Capstone Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0736848244).

- ↑ The Blackfeet Nation Manataka American Indian Council. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ↑ George Bird Grinnell, Blackfoot Lodge Tales: The Story Of A Prairie People (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2010, ISBN 978-1163786611).

- ↑ Mark David Spence, Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0195142433), 80.

- ↑ Blackfeet Religion.www.accessgeneology.com. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ F. David Peat, Blackfoot Physics: A Journey into the Native American Universe (Fourth Estate Ltd., 1996, ISBN 1857024567) Chapter 1: Spirits of Renewal Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ↑ John C. Ewers. The Horse in Blackfoot Culture. (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Library, 1955), 295.

- ↑ Ewers 1955, 240.

- ↑ Ron Cherry, Lepidoptera in the Mythology of Native Americans. www.insects.org. Retrieved on April 6, 2007.

- ↑ Barry Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia. (Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0195138975)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blackfoot Gallery Committee. The Story of the Blackfoot People: Nitsitapiisinni. Tonawanda, NY: Firefly Books, 2001. ISBN 1552975835

- Ewers, John C. The Horse in Blackfoot Culture: With Comparative Material from Other Western Tribes. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Library, 1955. ASIN B0030T1C7I

- Gibson, Karen Bush. The Blackfeet: People of the Dark Moccasins. Mankato, MN: Capstone Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0736848244

- Grinnell, George Bird. Blackfoot Lodge Tales: The Story Of A Prairie People. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2010 (original 1892). ISBN 978-1163786611

- Hassrick, Royal B. The Colorful Story of North American Indians. New York, NY: Book Sales, Inc., 1975. ISBN 978-0706403602

- Murdoch, David S. North American Indian. New York, NY: DK Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-0756610814

- Peat, F. David. Blackfoot Physics: A Journey into the Native American Universe. London: Fourth Estate Ltd, 1996. ISBN 1857024567

- Pritzker, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia. Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195138771

- Spence, Mark David. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195142433

- Taylor, Colin. What Do We Know About The Plains Indians? New York, NY: Peter Bedrick Books, 1993. ISBN 978-0872262614

External Links

All links retrieved October 31, 2023.

- Blackfeet Nation

- Native Languages of the Americas: Blackfoot (Siksika, Peigan, Piegan, Kainai, Blackfeet)

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.