Camel

| Camels | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bactrian Camel, Camelus bactrianus

Dromedary, Camelus dromedarius

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Camelus bactrianus |

Camel is the common name for large, humped, long-necked, even-toed ungulates comprising the mammalian genus Camelus of the Camelidae family. There are two extant species of camels, the Dromedary or Arabian Camel, Camelus dromedarius, which has a single hump, and the Bactrian camel, Camelus bactrianus, which has two humps. They have been domesticated and used as a beast of burden and for production of milk, wool, and meat, although some wild populations of the Bacterian camel exist in the Gobi Desert of China and Mongolia. The IUCN (World Conservation Union) lists the "critically endangered" Wild Bactrian camel with the species name Camelus ferus and the domesticated form as C. bactrianus, while some list the wild form as the subspecies Camelus bactrianus ferus (Hare 2007).

The camel's unique adaptations to its environment—a hump storing fat for conversion to water, nostrils that trap water vapor, thick fur to insulate from intense heat, long legs to keep the body distant from the hot ground, long eyelashes to protect against sand, and many more—add to the wonder of nature for humans and the usefulness of the camel for societies in that part of the world.

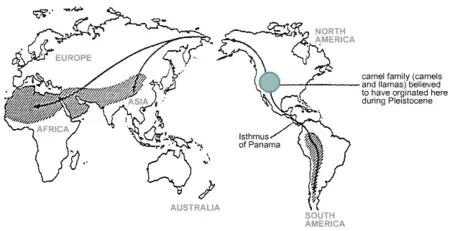

The fact that camels are found in Asia and Africa and their closest relatives (llamas, etc.) are found in South America, yet no camels presently exist in North America, lead to the speculation, based on the theory of descent with modification, that fossil camels would be found in North America (Mayr 2001). Indeed, such fossils, believed to be ancestral to both lineages, have been found, supporting the view that newer forms of life come on the foundation of earlier forms.

Description

In addition to the two species of camels (genus Camelus), extant members of the Camelidae family include two other genera with two species each, Lama (llama, guanaco) and Vicugna (alpaca, vicuña). At times the term camel is used more broadly to describe any of the six camel-like creatures in the family Camelidae: the two true camels and the four South American camelids.

Although considered ruminants—any even-toed, hooved animal that digests its food in two steps, first by eating the raw material and regurgitating a semi-digested form known as cud, then eating (chewing) the cud—camelids do not belong to the suborder Ruminantia but rather Tylopoda. Ruminantia includes the commonly known ruminants of cattle, goats, sheep, giraffes, bison, buffalo, deer, antelope, and so forth. The camelids differ from those of Ruminantia in several ways. They have a three-chambered rather than a four-chambered digestive tract; an upper lip that is split in two with each part separately mobile; an isolated incisor in the upper jaw; and, uniquely among mammals, elliptical red blood cells and a special type of antibodies lacking the light chain, besides the normal antibodies found in other species.

Camelids have long legs that, because they lack tensor skin to bridge between thigh and body, look longer still. They do not have hooves, rather a two-toed foot with toenails and a soft footpad (Tylopoda is Latin for "padded foot"). The main weight of the animal is borne by these tough, leathery sole-pads.

Among the two species of camels, the Dromedary camel is native to the dry and desert areas of western Asia and East Africa, and the Bactrian camel is native to central and east Asia. In addition to the Bactrian camel having two humps and the Dromedary having one hump, the Bactrian camel tends to be a stockier, hardier animal able to survive the scorching desert heat of northern Iran to the frozen winters in Tibet. The Dromedary tends to be taller and faster.

A fully-grown adult camel stands about 1.85 meters (6 feet) at the shoulder and 2.15 meters (7 feet) at the hump. The hump rises about 30 inches out of its body. Camels can run up to 40 mph in short bursts, and sustain speeds of up to 25 mph. The average life expectancy of a camel is 50 to 60 years.

Humans first domesticated camels between 3,500–3,000 years ago. It is thought that the Bactrian camel was domesticated independently from the Dromedary sometime before 2500 B.C.E. and the Dromedary between 4000 B.C.E. and 2000 B.C.E. (Al-Swailem et al. 2007).

The name camel comes to English via the Greek κάμηλος (kámēlos) from the Hebrew gamal or Arabic Jamal.

Adaptations

Camels are well known for their humps. However, they do not store water in them as is commonly believed, though they do serve this purpose through roundabout means. Their humps are actually a reservoir of fatty tissue. When this tissue is metabolized, it is not only a source of energy, but yields, through reaction with oxygen from the air, 1,111 grams of water per 1,000 grams of fat converted.

Camels' ability to withstand long periods without water is due to a series of physiological adaptations, as described below.

Their red blood cells have an oval shape, unlike those of other mammals, which are circular. This is to facilitate their flow in a dehydrated state. These cells are also more stable in order to withstand high osmotic variation without rupturing, when drinking large amounts of water (20-25 gallons in one drink) (Eitan et al. 1976).

The kidneys of a camel are very efficient. Urine comes out as a thick syrup and their feces are so dry that they can fuel fires.

Camels are able to withstand changes in body temperature and water content that would kill most other animals. Their temperature ranges from 34°C (93°F) at night up to 41°C (106°F) at day, and only above this threshold will they begin to sweat. The upper body temperature range is often not reached during the day in milder climatic conditions and therefore the camel may not sweat at all during the day. Evaporation of their sweat takes place at the skin level, not at the surface of their coat, thereby being very efficient at cooling the body compared to the amount of water lost through sweating. This ability to fluctuate body temperature and the efficiency of their sweating allows them to preserve about five liters of water a day.

A feature of their nostrils is that a large amount of water vapor in their exhalations is trapped and returned to the camel's body fluids, thereby reducing the amount of water lost through respiration.

Camels can withstand at least 20-25 percent weight loss due to sweating (most mammals can only withstand about 3-4 percent dehydration before cardiac failure results from the thickened blood). A camel's blood remains hydrated even though the body fluids are lost; until this 25 percent limit is reached.

Camels eating green herbage can ingest sufficient moisture in milder conditions to maintain their body's hydrated state without the need for drinking.

A camel's thick coat reflects sunlight. A shorn camel has to sweat 50 percent more to avoid overheating. The thick fur also insulates them from the intense heat that radiates from hot desert sand. Their long legs help by keeping them further from the hot ground. Camels have been known to swim if given the chance.

The mouth of a camel is very sturdy, able to chew thorny desert plants. Long eyelashes and ear hairs, together with sealable nostrils, form an effective barrier against sand. Their pace (moving both legs on one side at the same time) and their widened feet help them move without sinking into the sand.

All member species of the camelids are known to have a highly unusual immune system, where part of the antibody repertoire is composed of immunoglobulins without light chains. Whether and how this contributes to their resistance to harsh environments is currently unknown.

Distribution and numbers

The almost 14 million Dromedaries alive today are domesticated animals, which most living in Somalia, Sudan, Mauritania, and nearby countries.

The Bactrian camel once had an enormous range, but is now reduced to an estimated 1.4 million animals, mostly domesticated. It is thought that there are about 1000 wild Bactrian camels in the Gobi Desert in China and Mongolia (Massicot 2006).

There is a substantial feral population (originally domesticated but now living wild) estimated at up to 700,000 in central parts of Australia, descended from individuals introduced as means of transport in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century. This population is growing at approximately 11 percent per year and in recent times the state government of South Australia has decided to cull the animals using aerial marksmen, because the camels use too much of the limited resources needed by sheep farmers. A small population of introduced camels, Dromedaries and Bactrians, survived in the Southwest United States until the 1900s. These animals, imported from Turkey, were part of the US Camel Corps experiment and used as draft animals in mines, and escaped or were released after the project was terminated. A descendant of one of these was seen by a backpacker in Los Padres National Forest in 1972. Twenty-three Bactrian camels were brought to Canada during the Cariboo Gold Rush.

Origins of camels

Camels and their relatives, the llamas, are found on two continents, with true camels in Asia and Africa, and llamas in South America (Mayr 2001). There are no camels in North America. Based on the evolutionary theory of descent with modification, it would be expected that camels once existed in North America but became extinct. Indeed, there was the discovery of a large fossil fauna of Tertiary camels in North America (Mayr 2001).

One proposal for the fossil record for the camel is that camels started in North America, from which they migrated across the Bering Strait into Asia and hence to Africa, and through the Isthmus of Panama into South America. Once isolated, they evolved along their own lines, producing the modern camel in Asia and Africa and llama in South America.

Camel hybrids

Camelus dromedarius (Dromedarian camels) and Camelus bactrianus (Bactrian camels) can produce viable hydrids, Camelus dromedarius hybridus, although it is believed the hybrid males are sterile (Hare 2007). Bactrian camels have two humps and are rugged cold-climate camels while Dromedaries have one hump and are desert dwellers. Dromedary-Bactrian hybrids, called Bukhts, are larger than either parent, have a single hump, and are good draft camels. The females can be mated back to a Bactrian to produce ¾-bred riding camels. These hybrids are found in Kazakhstan.

The cama is a camel/llama hybrid bred by scientists who wanted to see how closely related the parent species were. The Dromedary is six times the weight of a llama, hence artificial insemination was required to impregnate the llama female (llama male to Dromedary female attempts have proven unsuccessful). Though born even smaller than a llama cria, the cama had the short ears and long tail of a camel, no hump, and llama-like cloven hooves rather than the Dromedary-like pads. At four years old, the cama became sexually mature and interested in llama and guanaco females. A second cama (female) has since been produced using artificial insemination. Because camels and llamas both have 74 chromosomes, scientists hope that the cama will be fertile. If so, there is potential for increasing size, meat/wool yield, and pack/draft ability in South American camels. The cama apparently inherited the poor temperament of both parents as well as demonstrating the relatedness of the New World and Old World camelids.

Uses

Camels continue to be a source of milk, meat, and wool. They also are used as beasts of burden— the Dromedary in western Asia, and the Bactrian camel further to the north and east in central Asia. They also have been employed for military use.

Notably, the camel is the only animal to have replaced the wheel (mainly in North Africa) where the wheel had already been established. The camel was not removed from the top of the transport industry in these areas until the wheel was combined with the internal combustion engine in the twentieth century.

Food

Dairy. Camel milk is a staple food of desert nomad tribes and is richer in fat and protein than cow's milk. Camel milk cannot be made into butter in the traditional churning method. It can be made into butter if it is soured first, churned, and then a clarifying agent is added or if it is churned at 24-25 °C, but times will vary greatly in achieving results. The milk can readily be made into yogurt. Butter or yogurt made from camel's milk is said to have a very faint greenish tinge. Camel milk is said to have many healthful properties and is used as a medicinal product in India; Bedouin tribes believe that camel milk has great curative powers if the camel's diet consists of certain plants. In Ethiopia, the milk is considered an aphrodisiac.

Meat. A camel carcass can provide a substantial amount of meat. The male dromedary carcass can weigh 400 kg or more, while the carcass of a male Bactrian can weigh up to 650 kg. The carcass of a female camel weighs less than the male, ranging between 250 and 350 kg, but can provide a substantial amount of meat. The brisket, ribs, and loin are among the preferred parts, but the hump is considered a delicacy and is most favored. It is reported that camel meat tastes like coarse beef, but older camels can prove to be tough and less flavorful.

Camel meat has been eaten for centuries. It has been recorded by ancient Greek writers as an available dish in ancient Persia at banquets, usually roasted whole. The ancient Roman emperor Heliogabalus enjoyed camel's heel. Camel meat is still eaten in certain regions, including Somalia where it is called Hilib geyl, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Libya, Sudan, Kazakhstan, and other arid regions where alternative forms of protein may be limited or where camel meat has had a long cultural history. Not just the meat, but also blood is a consumable item as is the case in northern Kenya, where camel blood is a source of iron, vitamin D, salts, and minerals (although Muslims do not drink or consume blood products).

A 2005 report issued jointly by the Saudi Ministry of Health and the United States Center for Disease Control details cases of human plague resulting from the ingestion of raw camel liver (Abdulaziz et al. 2005). According to Jewish tradition, Camel meat and milk are taboo. Camels possess only one of the two Kosher criteria; although they chew their cuds, they do not possess split hooves.

Wool

Bactrian camels have two coats: the warm inside coat of down and a rough outer coat, which is long and hairy. They shed their fiber in clumps consisting of both coats, which can be gathered and separated. They produce approximately 7 kg (15 lb) of fiber annually. The fiber structure is similar to cashmere wool. The down is usually 2 to 8 cm (1–3 inches) long. While camel down does not felt easily, it may be spun into a yarn for knitting.

Military uses of camels

Attempts have been made to employ camels as cavalry and dragoon mounts and as freight animals in lieu of horses and mules in many regions of the world. The camels mostly are used in combat because of their hardiness outside of combat and their ability to scare off horses in close ranges. The horses are said react to the smell of camels and therefore the horses in the vicinity are harder to control. The United States Army had an active camel corps stationed in California in the nineteenth century, and the brick stables may still be seen at the Benicia Arsenal in Benicia, California, now converted to artist's and artisan's studio spaces.

Camels have been used in wars throughout Africa, and also in the East Roman Empire as auxiliary forces known as Dromedarii recruited in desert provinces.

In some places, such as Australia, some of the camels have become feral and are considered to be dangerous to travelers on camels.

Image Gallery

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). 2005. National plan sought to manage camel population. ABC News Online. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- Bin Saeed, A. A., N. A. Al-Hamdan, and R. E. Fontaine. 2005. Plague from eating raw camel liver. Emerg Infect Dis September 2005. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- Bulliet, R. W. 1975. The Camel and the Wheel. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674091302.

- Davidson, A. 1999. The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192115790.

- Eitan, A., B. Aloni, and A. Livne. 1976. Unique properties of the camel erythrocyte membrane, II. Organization of membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 426(4): 647-658.

- Hare, J. 2007. Camelus ferus. IUCN. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- Massicot, P. 2006. Wild Bactrian camel, Camelus bactrianus (Camelus bactrianus ferus). Animal Info. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- Mayr, E. 2001. What Evolution Is. Basic Books. ISBN 0465044255

- Wilson, R. T. 1984. The Camel. London: Longman. ISBN 0582775124.

- Yagil, R. 1982. Camels and camel milk. FAO. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.