| Central Intelligence Agency CIA | |

Seal of the Central Intelligence Agency | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 26, 1947 |

| Preceding Agency | Central Intelligence Group |

| Headquarters | Langley, Virginia, United States |

| Employees | Classified |

| Annual Budget | Classified |

| Minister Responsible | John Michael McConnell, Director of National Intelligence |

| Agency Executives | General Michael Hayden USAF, Director Stephen Kappes, Deputy Director Michael Morell, Associate Deputy Director |

| Website | |

| www.cia.gov | |

| Footnotes | |

| [1][2][3] | |

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is an intelligence-gathering agency of the United States government whose primary mission today is collecting secret information from abroad through human agents. Created in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack to centralize all intelligence-gathering efforts by the U.S. government, its three functions are divided according to intelligence collection, intelligence analysis, and technical services. It also has the mandate to conduct covert action, semi-secret political, or paramilitary operations where the U.S. government's hand is not directly visible. It also conducts counterintelligence against foreign-government intelligence services. The CIA's covert operations have caused much controversy for the agency, raising questions about the legality, morality, and effectiveness of such operations.

The CIA is restricted from operating inside the United States, although it collects some intelligence from American visitors who return from overseas travel or individuals living in the U.S with access to foreign intelligence. The FBI is the lead domestic intelligence agency.

The CIA's elite division is called the Directorate of Operations (DO), also known as the Clandestine Service, that at its height in the 1980s, numbered around 10,000 specialists in espionage, agent recruitment, and covert action.

Until recently, the CIA director performed the dual functions of agency director and Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), the nominal head of all U.S. intelligence agencies. Under reform legislation passed in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks and failures related to Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction programs, the CIA was subsumed under the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the CIA director no longer acts as DCI. The agency has been refocused as the primary human-intelligence gathering agency of the government.

CIA headquarters is in the community of Langley in the McLean, Virginia, a few miles northwest from downtown Washington, D.C., along the Potomac River.

History and operations

Creation

The Central Intelligence Agency was created by Congress with passage of the National Security Act of 1947, signed into law by President Harry S. Truman. It is the descendant of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) of World War II, which was dissolved in October 1945, and its functions transferred to the State and War Departments. However, the need for a centralized postwar intelligence-gathering operation was clearly recognized.

Eleven months earlier, in 1944, William J. Donovan (also known as Wild Bill Donovan), the OSS's creator, proposed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt creating a new espionage organization directly supervised by the President. Under Donovan's plan, a powerful, centralized civilian agency would coordinate all the intelligence services. He also proposed that this agency have authority to conduct "subversive operations abroad," but no police or law enforcement functions, either at home or abroad.

President Harry S. Truman, established the Central Intelligence Group in January 1946, over objections from the State Department and the FBI, who saw the creation of the agency as a rival to their own functions. Later, under the National Security Act of 1947, the National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency were established. Rear Admiral Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter was appointed as the first Director of Central Intelligence.

The now declassified National Security Council Directive on the Office of Special Projects, June 18, 1948 (NSC 10/2), provided the operating instructions for the CIA's covert operations:

Plan and conduct covert operations which are conducted or sponsored by this government against hostile foreign states or groups or in support of friendly foreign states or groups but which are so planned and conducted that any U.S. Government responsibility for them is not evident to unauthorized persons and that if uncovered the U.S. Government can plausibly disclaim any responsibility for them. Covert action shall include any covert activities related to: Propaganda; economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition, and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance movements, guerrillas and refugee liberation groups, and support of indigenous anti-Communist elements in threatened countries of the free world.

Fighting communism

The CIA was successful in limiting native Communist influence in France and Italy, notably in the 1948 Italian election. It also cooperated in a clandestine NATO "stay-behind" operation in Italy called Operation Gladio, which was set up in Western Europe, intended to counter a Warsaw Pact invasion of Western Europe. In addition, the CIA managed to acquire the Rosenholz files, containing the list of foreign spies of the Stasi, in the former German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

The CIA also helped recruit many scientists who had worked in Nazi Germany to aid the United States. Several former Nazi operational agents were also reportedly recruited as United States' secret agents.

In 1949, the Central Intelligence Agency Act (Public Law 81-110) was passed, permitting the agency to use confidential fiscal and administrative procedures, and exempting it from most of the usual limitations on the use of federal funds. The act also exempted the CIA from having to disclose its "organization, functions, officials, titles, salaries, or numbers of personnel employed." The act also created the program "PL-110," to handle defectors and other "essential aliens" who fall outside normal immigration procedures, as well as giving those persons cover stories and economic support.

In the 1950s, with Europe stabilizing along the Iron Curtain, the CIA worked to limit the spread of Soviet influence elsewhere around the world, especially in the poor countries of the Third World. Encouraged by DCI Allen Dulles, clandestine operations quickly dominated the organization's actions.

In 1950, the CIA organized the Pacific Corporation, the first of many CIA private enterprises used effectively by the CIA both for intelligence gathering and covert operations. In 1951, the Columbia Broadcasting System began cooperating with the CIA, as did several other news-gathering groups in later years. It also pioneered the use of new technologies in intelligence work, including the famous U-2 high altitude spy plane.

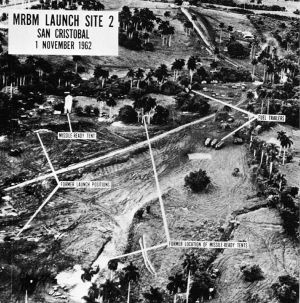

One of the CIA's major successes came during the Cuban Missile Crisis, which began on October 16, 1962. On that day, President John F. Kennedy was informed that a U-2 mission flown over western Cuba two days before had taken photographs of Soviet-nuclear missile sites. The event was a watershed for the intelligence community and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), in particular. It demonstrated that the technological collection capabilities so painstakingly constructed to monitor the Soviet Union had matured to give the U.S. intelligence community an unmatched ability to provide policymakers with sophisticated warning and situational awareness. The CIA took the lead in developing aerial and space photographic systems.

Particularly during the Cold War, the CIA supported numerous governments opposed to Communist insurgencies and Marxist political movements. Some of these were led by military dictators friendly to perceived United States' geopolitical interests. In some cases, the CIA reportedly supported coups against elected governments.

The CIA also supported the Congress of Cultural Freedom, which published literary and political journals such as Encounter (as well as Der Monat in Germany and Preuves in France), and hosted dozens of conferences bringing together some of the most eminent Western thinkers; it also gave assistance to intellectuals behind the Iron Curtain.

Controversy mounts

In the early 1970s, revelations about past CIA activities, such as assassinations of foreign leaders and illegal domestic spying on U.S. citizens, provided opportunities to execute Congressional oversight of U.S. intelligence operations. In 1973, then-DCI James R. Schlesinger had commissioned reports—known as the "Family Jewels"—on illegal activities by the Agency. In December 1974, Investigative journalist Seymour Hersh broke the news of the "Family Jewels" in a front-page article in the New York Times, revealing that the CIA had assassinated foreign leaders, and had conducted surveillance on some 7,000 American citizens involved in the antiwar movement (Operation CHAOS). The CIA also suffered a major public relations setback when it was revealed that the infamous burglary of the Watergate headquarters of the Democratic Party was conducted by ex-CIA agents.

Congress responded in 1975, investigating the CIA in the Senate via the Church Committee, chaired by Senator Frank Church (D-Idaho), and in the House of Representatives via the Pike Committee, chaired by Congressman Otis Pike (D-NY). In addition, President Gerald Ford created the Rockefeller Commission to investigate CIA activities within the U.S. and issued a directive prohibiting the assassination of foreign leaders.

Under the Carter Administration, CIA Director Adm. Stansfield Turner carried out what became known as the “Halloween Massacre,” firing large numbers of the agency’s most experienced operations officers with a terse note. The action was part of a shift in emphasis away from human-based spying operations to electronic spying. Today, the CIA is working to recover from the loss of its human spying capabilities, shortcomings that were highlighted by the failures related to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

A high point for the CIA was its running, along with British intelligence, of a Soviet military spy inside the GRU military intelligence service, Colonel Oleg Penkovsky. Penkovsky provided documents on Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile capabilities that allowed the United States to understand the threat it was facing from Moscow’s nuclear missiles. It is an example today of the kind of intelligence that can only be provided by human spies.

Under CIA Counterintelligence Chief James Jesus Angleton, the CIA imprisoned Soviet defector Yuri Nosenko, whom Angleton believed to be an agent sent to provide disinformation to the CIA. Angleton had become close to another defector, Anatoli Golitsyn, who reported that a secret unit within the Kremlin was engaged in strategic disinformation against the West. The dueling defectors set off an internal struggle within the CIA and led to Angleton’s "mole hunt," a search for Soviet penetration agents working within the CIA.

Angleton had sought to reorient the CIA into a strategic counterintelligence agency, whose main goal would be targeting the Soviet KGB and its sister services with the initiative of bringing down the Soviet empire. Angleton, however, lost out in the power struggle to CIA Director William Colby, who favored a more traditional intelligence and covert action approach.

The Farewell Dossier—a collection of documents containing intelligence gathered and handed over to NATO by the KGB defector Colonel Vladimir Vetrov (code-named "Farewell")—in 1981-82, revealed massive Soviet espionage on Western technology. The CIA created a successful counter-espionage program which involved giving defective technologies to Soviet agents.

In 1983, the CIA had more spies working inside the Soviet Union than at any time in its history. Infamous CIA operative Aldrich Ames would betray 25 active agents, some working at senior levels within the Soviet establishment. Many of these were taken to prison and then shot in the back of the head, so that the exit wound would render the face unrecognizable. In return, Ames received over $1.3 million in payments from the KGB from 1985-91. The total would eventually rise to $4 million. Ames was finally caught after a CIA mole-hunting team—with the assistance of the FBI—uncovered Ames's access to compromised cases and his suspect personal finances.

Repercussions from the Iran-Contra arms smuggling scandal included the creation of the Intelligence Authorization Act in 1991. It required an authorizing chain of command, including an official presidential report and the informing of the House and Senate Intelligence Committees.

In 1996, the U.S. House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence issued a congressional report estimating that the clandestine service part of the intelligence community "easily" breaks "extremely serious laws" in countries around the world 100,000 times every year.

Some of the post-Watergate restrictions upon the Central Intelligence Agency were lifted after the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and The Pentagon. Critics charge this violates the requirement in the U.S. Constitution that the federal budget be openly published.

In the findings of the independent National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States released on July 22, 2004, detailed several failures of the CIA in taking proper measures related to the September 11, 2001 attacks were called into account:

- "The CIA was limited in its effort to try to capture al Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden and his lieutenants in Afghanistan by the agency's use of proxies."

- "The failure of the CIA and FBI to communicate with each other… led to missed 'operational opportunities' to hinder or break the terror plot."

- "The CIA did not put 9/11 hijacker Khalid Almihdhar on a 'watch list' or notify the FBI when he had a U.S. visa in January 2000, or when he met with a key figure in the USS ''Cole'' bombing. And the CIA failed to develop plans to track Almihdhar, or hijacker Nawaf Alhazmi when he obtained a U.S. visa and flew to Los Angeles."

On November 5, 2002, newspapers reported that Al-Qaeda operatives in a car traveling through Yemen had been killed by a missile launched from a CIA-controlled Predator drone. On May 15, 2005, it was reported that another of these drones had been used to assassinate Al-Qaeda figure Haitham al-Yemeni inside Pakistan.

Reorganization

In the same year President George W. Bush appointed the CIA to be in charge of all human intelligence and manned spying operations. This was the culmination of a years-old turf war regarding influence, philosophy, and budget between the Defense Intelligence Agency of The Pentagon and the CIA. The Pentagon, through the DIA, wished to take control of the CIA's paramilitary operations and many of its human assets. The CIA, which has for years held that human intelligence is the core of the agency, successfully argued that the CIA's decades-long experience with human resources and civilian oversight made it, rather than the DIA, the ideal choice. Thus, the CIA was given charge of all United States' human intelligence, but as a compromise, The Pentagon was authorized to include increased paramilitary capabilities in future budget requests. Despite reforms which led it back to what the CIA considers its traditional principal capacities, the CIA Director's position has lost influence in the White House. For years, the Director of the CIA met regularly with the President to issue daily reports on ongoing operations. After the creation of the post of Director of National Intelligence, the report is now given by the DNI, who oversees all United States' Intelligence activities.

On July 9, 2004, the Senate Report of Pre-war Intelligence on Iraq of the Senate Intelligence Committee reported that the CIA exaggerated the danger presented by weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, largely unsupported by the available intelligence.

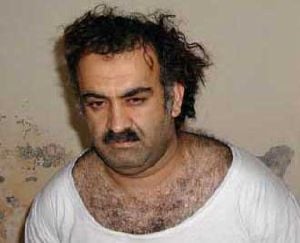

Earlier, in Novemeber 2002, the CIA successfully ended the life of Qaed Salim Sinan al-Harethi, a prominent member of Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda terrorist network, through a Predator drone attack in Yemen. It has also been involved in identifying, capturing, and interrogating numerous terrorists, as well as in operations assisting troops fighting al Qaeda in Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2003, the CIA reportedly assisted in the capture of al Qaeda operations director Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who was later reported to have cooperated with CIA interrogators, providing valuable information on al Qaeda methods, plans, and personnel. On January 13, 2006, the CIA launched an airstrike on Damadola, a Pakistani village near the Afghan border, where they believed Ayman al-Zawahiri was located. The airstrike killed a number of civilians, but al-Zawahiri escaped. Because al-Zawahiri is named as a terrorist enemy combatant by the United States, this and similar attacks are not covered under Executive Order 12333, which banned assassinations. Many of the CIA's activities in the war on terror remain undisclosed for security reasons.

Current organization

Agency seal

The heraldic symbol of the CIA consists of three representative parts: The left-facing bald eagle head atop, the compass star (or compass rose), and the shield. The eagle is the national bird, standing for strength and alertness. The 16-point compass star represents the CIA's world-wide search for intelligence outside the United States, which is then reported to the headquarters for analysis, reporting, and re-distribution to policymakers. The compass rests upon a shield, symbolic of defense and intelligence.

Structure

- Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (DCIA)—The head of the CIA is given the title of the DCIA. The act that created the CIA in 1947, also created a Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) to serve as head of the United States intelligence community, act as the principal adviser to the President for intelligence matters related to the national security, and serve as head of the Central Intelligence Agency. The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, amended the National Security Act to provide for a Director of National Intelligence who would assume some of the roles formerly fulfilled by the DCI, with a separate Director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

- Deputy Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (DDCIA)—Assists the Director in his duties as head of the CIA and exercises the powers of the Director when the Director’s position is vacant or in the Director’s absence or disability.

- Associate Deputy Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (ADD)—Created July 5, 2006, the ADD was delegated all authorities and responsibilities vested previously in the post of Executive Director. The post of Executive Director, which was responsible for managing the CIA on a day-to-day basis, was simultaneously abolished.

- Associate Director for Military Support (AD/MS)—The DCIA's principal adviser and representative on military issues. The AD/MS coordinates Intelligence Community efforts to provide Joint Force commanders with timely, accurate intelligence. The AD/MS also supports Department of Defense officials who oversee military intelligence training and the acquisition of intelligence systems and technology. A senior general officer, the AD/MS ensures coordination of Intelligence Community policies, plans, and requirements relating to support to military forces in the intelligence budget.

Relationship with other agencies

The National Intelligence Council, which oversees production of National Intelligence Estimates, was transferred under reform legislation to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. It is believed to make use of the product derived from surveillance satellites of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and the signal interception capabilities of the National Security Agency (NSA), including the ECHELON system, the surveillance aircraft of the various branches of the U.S. armed forces and the analysts of the State Department, and Department of Energy. At one point, the CIA even operated its own fleet of U-2 and A-12 OXCART surveillance aircraft.

The agency has also operated alongside regular military forces, and also employs a group of clandestine officers with paramilitary skills in its Special Activities Division. The CIA also has strong links with other foreign intelligence agencies such as the UK's Secret Intelligence Service, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Israel's Mossad, and the Australian Secret Intelligence Service.

Further, the CIA is currently believed to be financing several Counter-terrorist Intelligence Centers.

Publications

One of the CIA's best-known publications, The World Factbook, is in the public domain and is made freely available without copyright restrictions because it is a work of the United States federal government.

Since 1955, the CIA has published an in-house professional journal known as Studies in Intelligence that addresses historical, operational, doctrinal, and theoretical aspects of the intelligence profession. Unclassified and declassified Studies articles, as well as other books and monographs, are made available by the CIA's Center for the Study of Intelligence on a limited basis through Internet and other publishing mechanisms.

In 2002, the CIA's Sherman Kent School for Intelligence Analysis began publishing the unclassified Kent Center Occasional Papers, aiming to offer "an opportunity for intelligence professionals and interested colleagues-—in an unofficial and unfettered vehicle-—to debate and advance the theory and practice of intelligence analysis."

Notes

- ↑ Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified. cia.gov (2006-07-28).

- ↑ Public affairs FAQ. cia.gov (July 28, 2006). Retrieved April 28, 2013. However, it was made public for several years in the late 1990s. In 1997 it was of $26.6 billion and in 1998 it was $26.7 billion

- ↑ Cloak Over the CIA Budget (1999-11-29). Retrieved April 28, 2013.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andrew, Christopher. For the President's Eyes Only. HarperCollins, 1996. ISBN 0-00-638071-9

- Baer, Robert. See No Evil: The True Story of a Ground Soldier in the CIA's War on Terrorism. Three Rivers Press, 2003. ISBN 1-4000-4684-X

- Bearden, Milton, & Risen, James. The Main Enemy: The Inside Story of the CIA's Final Showdown With the KGB. Random House, 2003. ISBN 0-679-46309-7

- Blum, William. Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II. Common Courage Press, 2003. ISBN 1-56751-252-6

- Ranelagh, John. The Agency, the Rise and Decline of the CIA. Touchstone Books, 1987. ISBN 978-0671639945

- Westerfield, H. Bradford. Inside CIA's Private World: Declassified Articles from the Agency's Internal Journal, 1955-1992. Yale University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-300-07264-3

External links

All links retrieved December 3, 2023.

- CIA official site. www.cia.gov.

- George Washington University National Security Archive. www.gwu.edu.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.