Cortisol

| |

| |

Cortisol

| |

| Systematic name | |

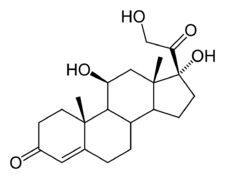

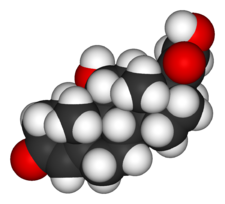

| IUPAC name 11,17,21-trihydroxy-,(11beta)- pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 50-23-7 |

| ATC code | H02AB09 (and others) |

| PubChem | 5754 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C21H30O5 |

| Mol. weight | 362.465 |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ? |

| Metabolism | ? |

| Half life | ? |

| Excretion | ? |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | C |

| Legal status | ? |

| Routes | Oral tablets, intravenously, topical |

Cortisol, known in medical use as hydrocortisone, is one of the major steroid hormones produced by the adrenal cortex, the outer layer of the adrenal gland of mammals. Cortisol is a vital hormone and is sometimes known as the stress hormone in humans, as it is involved in the body's natural response to physical or emotional stress.

Cortisol increases blood pressure, blood sugar levels, and suppresses the immune system (immunosuppressive action). It promotes breakdown of glycogen, lipids, and proteins, and reduces protein levels in most body cells (excluding the gastrointestinal tract and the liver).

Cortisol reflects the intricate coordination of systems in the body. When there is a stressful situation, such as illness, fear, pain, or physical exertion, a whole series of impacts take place that lead to production of cortisol. These include the release of a hormone from the hypothalamus, that stimulates the pituitary gland to produce yet another hormone, that stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce cortisol, which can then act to help the body deal with the stress. When the stress is removed, the body returns to homeostasis. This is but one example of many systems harmoniously working together, with each gland providing a function in service to the body, even if its impact is in a distant location. When this intricate harmony breaks down, albeit rarely, then diseases such as Cushing's syndrome and Addison's disease may result.

In pharmacology, the synthetic form of cortisol is referred to as hydrocortisone, and is used to treat allergies and inflammation as well as cortisol production deficiencies. When first introduced as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, it was referred to as Compound E.

Overview

Like cortisone, cortisol is a corticosteroid, a term that refers to steroid hormones that are produced in the adrenal cortex of the body. Among corticosteroids, cortisol and cortisone are classified as glucocorticoids, a group that controls protein, fat, carbohydrate, and calcium metabolism. (Mineralocorticoids, the other group of corticosteroids, regulates salt and potassium levels and water retention.)

Another hormone produced in the adrenal glands, albeit in the adrenal medulla, not the adrenal cortex like corticosteroids, is adrenaline (epinephrine), which like cortisol, deals with stress.

The chemical formula for cortisol is C21H30O5.

Under conditions of stress, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is released by the hypothalamus. After traveling to the pituitary gland, CRH stimulates the production adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH or corticotropin) through cleavage of the large glycoprotein pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). ACTH then travels to the adrenal cortex, via the bloodstream, stimulating cortisol to be produced and released. Cortisol then is transported to tissues. The main function of ACTH, a polypeptide hormone, is to stimulate the adrenal glands to release cortisol in response to stress.

Physiology

Function

In normal release, cortisol (like other glucocorticoid agents) has widespread actions that help restore homeostasis after stress. (These normal endogenous functions are the basis for the physiological consequences of chronic stress—prolonged cortisol secretion.)

- It acts as a physiological antagonist to insulin by promoting glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen), breakdown of lipids (lipolysis) and proteins, and mobilization of extrahepatic amino acids and ketone bodies. This leads to increased circulating glucose concentrations (in the blood). There is a decreased glycogen formation in the liver (Freeman 2002). Prolonged cortisol secretion causes hyperglycemia.

- It can weaken the activity of the immune system. Cortisol prevents proliferation of T-cells by rendering the interleukin-2 producer T-cells unresponsive to interleukin-1 (IL-1), and unable to produce the T-cell growth factor (Palacios and Sugawara 1982). It reflects leukocyte redistribution to lymph nodes, bone marrow, and skin. Acute administration of corticosterone (the endogenous Type I and Type II receptor agonist), or RU28362 (a specific Type II receptor agonist), to adrenalectomized animals induced changes in leukocyte distribution.

- It lowers bone formation, thus favoring development of osteoporosis in the long term. Cortisol moves potassium into cells in exchange for an equal number of sodium ions (Knight et al. 1955). This can cause a major problem with the hyperkalemia of metabolic shock from surgery.

- It helps to create memories when exposure is short-term; this is the proposed mechanism for storage of flash bulb memories. However, long-term exposure to cortisol results in damage to cells in the hippocampus. This damage results in impaired learning.

- It increases blood pressure by increasing the sensitivity of the vasculature to epinephrine and norepinephrine. In the absence of cortisol, widespread vasodilation occurs.

- It inhibits the secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), resulting in feedback inhibition of ACTH secretion. Some researchers believe that this normal feedback system may break down when animals are exposed to chronic stress.

- It increases the effectiveness of catecholamines.

- It allows for the kidneys to produce hypotonic urine.

In addition to the effects caused by cortisol binding to the glucocorticoid receptor, because of its molecular similarity to aldosterone, it also binds to the mineralocorticoid receptor. (It binds with less affinity to it than aldosterone does, but the concentration of blood cortisol is higher than that of blood aldosterone.)

Most serum cortisol, all but about four percent, is bound to proteins including corticosteroid binding globulin (CBG), and serum albumin. Only free cortisol is available to most receptors.

Diurnal variation

ACTH production is related to the circadian rhythm in many organisms, with secretion peaking during the morning hours. Thus, the amount of cortisol present in the serum likewise undergoes diurnal variation, with the highest levels present in the early morning, and the lowest levels present around midnight, three to five hours after the onset of sleep. Information about the light/dark cycle is transmitted from the retina to the paired suprachiasmatic nuclei in the hypothalamus. The pattern is not present at birth (estimates of when it starts vary from two weeks to nine months (Weerth et al. 2003).

Changed patterns of serum cortisol levels have been observed in connection with abnormal ACTH levels, clinical depression, psychological stress, and such physiological stressors as hypoglycemia, illness, fever, trauma, surgery, fear, pain, physical exertion, or extremes of temperature.

There is also significant individual variation, although a given person tends to have consistent rhythms.

Bioynthesis and metabolism

Biosynthesis

Cortisol is synthesized from pregnenolone (sometimes progesterone, depending on the order of enzymes working). The change involves hydroxylation of C-11, C-17, and C-21, the dehydrogenation of C-3, and the isomerization of the C-5 double bond to C-4. The synthesis takes place in the zona fasciculata of the cortex of the adrenal glands. (The name cortisol comes from cortex.) While the adrenal cortex also produces aldosterone (in the zona glomerulosa) and some sex hormones (in the zona reticularis), cortisol is its main secretion. The medulla of the adrenal gland lies under the cortex and mainly secretes the catecholamines, adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), under sympathetic stimulation (more epinephrine is produced than norepinephrine, in a ratio 4:1).

The synthesis of cortisol in the adrenal gland is stimulated by the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH); production of ACTH is in turn stimulated by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), released by the hypothalamus. ACTH increases the concentration of cholesterol in the inner mitochondrial membrane (via regulation of STAR (steroidogenic acute regulatory) protein). The cholesterol is converted to pregnenolone, catalysed by Cytochrome P450SCC (side chain cleavage).

Metabolism

Cortisol is metabolized by the 11-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase system (11-beta HSD), which consists of two enzymes: 11-beta HSD1 and 11-beta HSD2.

- 11-beta HSD1 utilizes the cofactor NADPH to convert biologically inert cortisone to biologically active cortisol.

- 11-beta HSD2 utilizes the cofactor NAD+ to convert cortisol to cortisone.

Overall the net effect is that 11-beta HSD1 serves to increase the local concentrations of biologically active cortisol in a given tissue, while 11-beta HSD2 serves to decrease the local concentrations of biologically active cortisol.

An alteration in 11-beta HSD1 has been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of obesity, hypertension, and insulin resistance, sometimes referred to the metabolic syndrome.

An alteration in 11-beta HSD2 has been implicated in essential hypertension and is known to lead to the syndrome of apparent mineralocorticoid excess (SAME).

Diseases and disorders

- Hypercortisolism: Excessive levels of cortisol in the blood result in Cushing's syndrome.

- Hypocortisolism, or adrenal insufficiency: If the adrenal glands do not produce sufficient amounts of cortisol. Addison's disease refers specifically to primary adrenal insufficiency, in which the adrenal glands themselves malfunction. Secondary adrenal insufficiency, which is not considered Addison's disease, occurs when the anterior pituitary gland does not produce enough adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) to adequately stimulate the adrenal glands. Addison's disease is far less common than Cushing's syndrome.

The relationship between cortisol and ACTH is as follows:

| Plasma Cortisol | Plasma ACTH | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Hypercortisolism (Cushing's syndrome) | ↑ | ↓ |

| Secondary Hypercortisolism (pituitary, Cushing's disease) | ↑ | ↑ |

| Primary Hypocortisolism (Addison's disease) | ↓ | ↑ |

| Secondary Hypocortisolism (pituitary) | ↓ | ↓ |

Pharmacology

As an oral or injectable drug, cortisol is also known as hydrocortisone. It is used as an immunosuppressive drug, given by injection in the treatment of severe allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis and angioedema, in place of prednisolone in patients who need steroid treatment but cannot take oral medication, and peri-operatively in patients on long-term steroid treatment to prevent an Addisonian crisis.

Hydrocortisone is given by topical application for its anti-inflammatory effect in allergic rashes, eczema, and certain other inflammatory conditions. Brand names include Aveeno®, Emocort®, Epifoam®, Sigmacort®, Hyderm®, NovoHydrocort® Cortoderm®, Efcortelan®, Fucidin-H®, Cortizone-10®, Cortaid®, and Lanacort®

It may also be injected into inflamed joints resulting from diseases such as gout.

Compared to prednisolone, hydrocortisone is about ¼ of the strength (for the anti-inflammatory effect only). Dexamethasone is about 40 times stronger than hydrocortisone. Nonprescription 0.5 percent or one percent hydrocortisone cream or ointment is available; stronger forms are prescription only.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- de Weerth, C., R. Zijl, and J. Buitelaar. 2003. "Development of cortisol circadian rhythm in infancy." Early Human Development 73(1-2): 39-52.

- Freeman, S. 2002. Biological Science. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0132187469.

- Guyton, A. C., and J. E. Hall. 2000. Textbook of Medical Physiology 10th edition. W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 072168677X.

- Knight, R. P., D. S. Kornfield, G. H. Glaser, and P. K. Bondy. 1955. Effects of intravenous hydrocortisone on electrolytes of serum and urine in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 15(2): 176-181.

- Palacios, R., and I. Sugawara. 1982. "Hydrocortisone abrogates proliferation of T cells in autologous mixed lymphocyte reaction by rendering the interleukin-2 Producer T cells unresponsive to interleukin-1 and unable to synthesize the T-cell growth factor." Scand J Immunol 15(1): 25-31.

| Hormones and endocrine glands - edit |

|---|

|

Hypothalamus: GnRH - TRH - CRH - GHRH - somatostatin - dopamine | Posterior pituitary: vasopressin - oxytocin | Anterior pituitary: GH - ACTH - TSH - LH - FSH - prolactin - MSH - endorphins - lipotropin Thyroid: T3 and T4 - calcitonin | Parathyroid: PTH | Adrenal medulla: epinephrine - norepinephrine | Adrenal cortex: aldosterone - cortisol - DHEA | Pancreas: glucagon- insulin - somatostatin | Ovary: estradiol - progesterone - inhibin - activin | Testis: testosterone - AMH - inhibin | Pineal gland: melatonin | Kidney: renin - EPO - calcitriol - prostaglandin | Heart atrium: ANP Stomach: gastrin | Duodenum: CCK - GIP - secretin - motilin - VIP | Ileum: enteroglucagon | Liver: IGF-1 Placenta: hCG - HPL - estrogen - progesterone Adipose tissue: leptin, adiponectin Target-derived NGF, BDNF, NT-3 |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.