Dacia

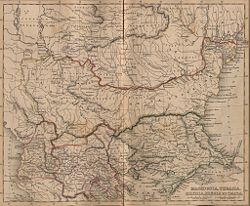

Dacia, in ancient history and geography was the land of the Dacians. It was named by the ancient Hellenes (Greeks) "Getae." Dacia was a large district of South Eastern Europe, bounded on the north by the Carpathians, on the south by the Danube, on the west by the Tisia or Tisa, on the east by the Tyras or Nistru, now in eastern Moldova. It corresponds in the main to modern Romania and Moldova, as well as parts of Hungary, Bulgaria and Ukraine. The capital of Dacia was Sarmizegetusa. The inhabitants of this district are generally considered as belonging to the Thracian nations. A kingdom of Dacia was in existence at least as early as the first half of the second century B.C.E. under King Oroles. This included fortified cities, a sophisticated mining industry, agriculture and ceramic art working. They Dacians also engaged in extensive external trade. In the first century C.E., King Boerebista carved out an empire that soon attracted the attention of the Romans. After his death, the empire split into fragments but was then reunified under King Decebalus.

After several confrontations between Dacia and Rome, Emperor Trajan began the process of subjugating the empire and incorporating it within his own. It was under Emperor Hadrian that Dacia was divided into Dacia Superior and Inferior, the former consisting of Transylvania, the latter Little Walachia. The territory remained troublesome, however with constant revolt. Hadrian almost withdrew but stayed to protect Romans who had settled there. Marcus Aurelius sub-divided Dacia into three provinces; each was headed by a procurator under a single consul. Dacia was also always vulnerable to attacks from the North and East. It served as a useful buffer between Rome and marauding Germanic tribes. Rome finally abandoned the province to the Visigoths after the death of Constantine I. Throughout history, this region was a place where different politics polities, empires, cultures, civilizations, and religions met, often creating conflict. Yet, despite centuries of division and foreign occupation, a rich culture emerged which blended East and West, creating a cultural bridge between rival civilizations. The legacy of ancient Dacians and of their successors, the Romanians, suggests that while civilizational clash is one option, mutual enrichment and a developing consciousness that we are all members of a single human family, is another.

Name

The Dacians were known as Geta (plural Getae) in Greek writings, and as Dacus (plural Daci) and Getae in Roman documents; also as Dagae and Gaete—see the late Roman map Tabula Peutingeriana. Strabo tells that the original name of the Dacians was "daoi," which could be explained with a possible Phrygian cognate "daos," meaning "wolf." This assumption is enforced by the fact that the Dacian standard, the Dacian Draco, had a wolf head.

It can be confusing that the geographical name "Dacia" was much later also used during the Middle Ages by the Roman Catholic Church for its northernmost province, namely Denmark-Norway-Sweden (Scandinavia) and even for Denmark alone. In some historical documents, members of royalty of that area have been called "of Dacia."

Geography

Towards the west Dacia may originally have extended as far as the Danube, where it runs from north to south at Waitzen (Vác). Julius Caesar in his De Bello Gallico (Battle for Gaul) (book 6) speaks of the Hercynian forest extending along the Danube to the territory of the Dacians. Ptolemy puts the eastern boundary of Dacia Trajana as far back as the Hierasus (Siret river, in modern Romania).

The extent and location of the later geographical entity Dacia varied in its four distinct historical periods;

- The Dacia of King Burebista (82–44 B.C.E.), stretching from the Southern Bug river in modern Ukraine to the Danube in modern Slovakia, and from the Balkan mountains in modern Bulgaria to Zakarpattia Oblast (Transcarpathia) in modern Ukraine

- The Roman province Dacia Trajana, established as a consequence of the Dacian Wars during 101–106 C.E., comprising the regions known today as Banat, Oltenia, and Transylvania.

- The later Roman province: Dacia Aureliana, reorganized as Dacia Ripensis (as military province) and Dacia Mediterranea (as civil province),[1] inside former Moesia Superior after the abandonment of former Dacia to the Goths and Carpians in 271.

Culture

Based on archaeological findings, the origins of the Dacian culture can be considered to have begun developing from north of the Danube river (south and east) to the Carpathian mountains, in the modern-day historical Romanian province of Muntenia and are identified as an evolution of the Iron Age Basarabi culture.

The Dacians had attained a considerable degree of civilization by the time they first became known to the Romans.

Religion

According to Herodotus History (book 4) account of the story of Zalmoxis (or Zamolxis), the Getae (speaking the same language as the Dacians - believed in the immortality of the soul, and regarded death as merely a change of country. Their chief priest held a prominent position as the representative of the supreme deity, Zalmoxis.[2] The chief priest was also the king's chief adviser. The Goth Jordanes in his Getica (The Origin and Deeds of the Goths), gives account of Dicineus (Deceneus), the highest priest of Buruista (Burebista) and considered the Dacians a related nation of the Goths.

Besides Zalmoxis, the Dacians believed in other deities such as Gebeleizis and Bendis. Zalmoxis is believed to have been a social and religious reformer who learned of the immortality of the soul while traveling in Egypt, returned to Dacia as a teacher and physician. He is said to have risen again three days after his death. Subsequently, he was venerated as the Dacian deity.

Society

Dacians were divided into two classes: the aristocracy (tarabostes) and the common people (comati). The aristocracy alone had the right to cover their heads and wore a felt hat (hence, pileati, their Latin name). The second class, who comprised the rank and file of the army, the peasants and artisans, might have been called capillati (in Latin). Their appearance and clothing can be seen on Trajan's Column.

Dacians had developed the Murus dacicus, characteristic to their complexes of fortified cities, like their capital Sarmizegetusa in today Hunedoara County, Romania. The degree of their urban development can be seen on Trajan's Column and in the account of how Sarmizegetusa was defeated by the Romans. The Romans identified and destroyed the water aqueducts or pipelines of the Dacian capital, only thus being able to end the long siege of Sarmizegetusa.

Greek and Roman chroniclers record the defeat and capture of Lysimachus in the third century B.C.E. by the Getae (Dacians) ruled by Dromihete, their military strategy, and the release of Lysimachus following a debate in the assembly of the Getae.

The cities of the Dacians were known as -dava, -deva, -δαυα ("-dawa" or "-dava," Anc. Gk.), -δεβα ("-deva," Byz. Gk.) or -δαβα ("-dava," Byz. Gk.).

Cities

- In Dacia: Acidava, Argedava, Burridava, Dokidava, Carsidava, Clepidava, Cumidava, Marcodava, Netindava, Patridava, Pelendava, Perburidava, Petrodaua, Piroboridaua, Rhamidaua, Rusidava, Sacidava, Sangidava, Setidava, Singidava, Tamasidava, Utidava, Zargidava, Ziridava, Sucidava—26 names altogether.

- In Lower Moesia (the present Northern Bulgaria) and Scythia minor (Dobrudja): Aedeba, Buteridava, Giridava, Dausadava, Kapidaua, Murideba, Sacidava, Scaidava (Skedeba), Sagadava, Sukidaua (Sucidava)—10 names in total.

- In Upper Moesia (the districts of Nish, Sofia, and partly Kjustendil): Aiadaba, Bregedaba, Danedebai, Desudaba, Itadeba, Kuimedaba, Zisnudeba—7 names in total.

Gil-doba, a village in Thracia, of unknown location.

Thermi-daua, a town in Dalmatia. Probably a Grecized form of Germidava.

Pulpu-deva, (Phillipopolis) today Plovdiv in Bulgaria.

Occupations

The chief occupations of Dacians were agriculture, apiculture, viticulture, livestock, ceramics, and metal working. The Roman province Dacia is represented on Roman Sestertius (coin) as a woman seated on a rock, holding aquila, a small child on her knee holding ears of grain, and a small child seated before her holding grapes.

They also worked the gold and silver mines of Transylvania. They carried on a considerable outside trade, as is shown by the number of foreign coins found in the country (see also Decebalus Treasure).

Commercial relations were flourishing for centuries, first with the Greeks, then with Romans, as we can find even today an impressive collection of gold currency used in various periods of Dacian history. The first coins produced by the Geto-Dacians were imitations of silver coins of the Macedonian kings Philip II and Alexander III (the Great). Early in the first century B.C.E., the Dacians replaced these with silver denarii of the Roman Republic, both official coins of Rome exported to Dacia and locally made imitations of them.

Language

The Dacians spoke an Indo-European language, but its characteristics are still disputed, due to insufficient archaeological evidence. Greek sources quote some place names, words, and even a list of about fifty plants written in Greek and Roman sources (see List of Dacian plant names), but this is still not enough to classify it, although many scholars assume it was part of the Satem branch.

Political entities

The migrations of the fore bearers of Ancient Greece (c. 750 B.C.E. or earlier) most likely originated at least in part from periodic swelled populations in the easy living found in the fertile plains of the region. Such migrations were in mythological times, and well before historical records. It is likely that trade with communities along the Danube via the Black sea was a regular occurrence, even in Minoan times (2700 to 1450 B.C.E.).

At the beginning of the second century B.C.E., under the rule of Rubobostes, a Dacian king in present-day Transylvania, the Dacians' power in the Carpathian basin increased by defeating the Celts who previously held the power in the region.

A kingdom of Dacia was in existence at least as early as the first half of the second century B.C.E. under King Oroles. Conflicts with the Bastarnae and the Romans (112 B.C.E.-109 B.C.E., 74 B.C.E.), against whom they had assisted the Scordisci and Dardani, greatly weakened the resources of the Dacians.

Under Burebista (Boerebista), a contemporary of Julius Caesar, who thoroughly reorganized the army and raised the moral standard of the people, the limits of the kingdom were extended to their maximum. The Bastarnae and Boii were conquered, and even the Greek towns of Olbia and Apollonia on the Black Sea (Pontus Euxinus) recognized Burebista's authority.

Indeed the Dacians appeared so formidable that Caesar contemplated an expedition against them; something his death prevented. About the same time, Burebista was murdered, and the kingdom was divided into four (or five) parts under separate rulers. One of these was Cotiso, whose daughter Augustus is said to have desired to marry and to whom Augustus betrothed his own five-year-old daughter Julia. He is well known from the line in Horace (Occidit Daci Cotisonis agmen.[3]

The Dacians are often mentioned under Augustus, according to whom they were compelled to recognize Roman supremacy. However, they were by no means subdued, and in later times to maintain their independence they seized every opportunity of crossing the frozen Danube during the winter and ravaging the Roman cities in the province of Moesia.

Roman conquest

Trajan turned his attention to Dacia, an area north of Macedon and Greece and east of the Danube that had been on the Roman agenda since before the days of Caesar[4] when they had beaten a Roman army at the Battle of Histria.[5] In 85, the Dacians had swarmed over the Danube and pillaged Moesia[6][7] and initially defeated an army the Emperor Domitian sent against them,[8] but the Romans were victorious in the Battle of Tapae in 88 C.E. and a truce was drawn up.[8]

From 85 to 89 C.E., the Dacians (under Decebalus) were engaged in two wars with the Romans.

In 87, the Roman troops under Cornelius Fuscus were defeated, and Cornelius Fuscus was killed by the Dacians under the authority of their ruler, Diurpaneus. After this victory, Diurpaneus took the name of Decebalus. The next year, 88 C.E., new Roman troops under Tettius Iullianus, gained a signal advantage, but were obliged to make peace owing to the defeat of Domitian by the Marcomanni, so the Dacians were really left independent. Even more, Decebalus received the status of "king client to Rome," receiving from Rome military instructors, craftsmen and even money.

Emperor Trajan recommenced hostilities against Dacia and, following an uncertain number of battles,[9] defeated the Dacian general Decebalus in the Second Battle of Tapae in 101 C.E.[10] With Trajan's troops pressing towards the Dacian capital Sarmizegethusa, Decebalus once more sought terms.[11] Decebalus rebuilt his power over the following years and attacked Roman garrisons again in 105 C.E. In response Trajan again marched into Dacia,[12] besieging the Dacian capital in the Siege of Sarmizegethusa, and razing it to the ground.[13] With Dacia quelled, Trajan subsequently invaded the Parthian empire to the east, his conquests taking the Roman Empire to its greatest extent. Rome's borders in the east were indirectly governed through a system of client states for some time, leading to less direct campaigning than in the west in this period.[14]

To expand the glory of his reign, restore the finances of Rome, and end a treaty perceived as humiliating, Trajan resolved on the conquest of Dacia and with it the capture of the famous Treasure of Decebalus and control over the Dacian gold mines of Transylvania. The result of his first campaign (101–102) was the siege of the Dacian capital Sarmizegethusa and the occupation of a part of the country. The second campaign (105–106) ended with the suicide of Decebalus, and the conquest of the territory that was to form the Roman province Dacia Traiana. The history of the war is given by Cassius Dio, but the best commentary upon it is the famous Column of Trajan in Rome.

Although the Romans conquered and destroyed the ancient Kingdom of Dacia, a large remainder of the land remained outside of Roman Imperial authority. Additionally, the conquest changed the balance of power in the region and was the catalyst for a renewed alliance of Germanic and Celtic tribes and kingdoms against the Roman Empire. However, the material advantages of the Roman Imperial system wasn't lost on much of the surviving aristocracy. Thus, most of the Romanian historians and linguists believe that many of the Dacians became Romanized - hence the later term "Romanian" for the people of the three principalities of Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia.

Nonetheless, Germanic and Celtic kingdoms, particularly the Gothic tribes made a slow progression toward the Dacian borders and soon within a generation were making assaults on the province. Ultimately, the Goths succeeded in dislodging the Romans and restoring the independence of Dacia following Aurelian's withdrawal, in 275 C.E. The province was abandoned by Roman troops, and, according to the Breviarium historiae Romanae by Eutropius, Roman citizens "from the town and lands of Dacia" were resettled to the interior of Moesia.

However, Romanian historians maintain that the bulk of the civilian population remained and a surviving aristocratic Dacian line revived the kingdom under Regalianus. About his origin, the Tyranni Triginta says he was a Dacian, a kinsman of Decebalus. Nonetheless, the Gothic aristocracy remained ascendant and through intermarriage soon dominated the kingdom which was absorbed into their larger empire.

During Diocletian, circa 296 C.E., in order to defend the Roman border, fortifications are erected by the Romans, on both banks of the Danube. By 336 C.E., Constantine the Great had reconquered the lost province, however following his death, the Romans abandoned Dacia for good.

Legacy

Following the rise of Islam, much of this area was conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Geo-politically, this was a frontier zone between empires and cultures, especially between East and West, between the Byzantines followed by Ottomans in the East and the European powers, including Hungary, Austria, Poland, Lithuania and Russia to the West and also to the North. The Dacians had traded with Greece and with Rome and, according to tradition, had contact with Egypt as well. Inevitably, this made the region vulnerable to conquest and for most of its history the former Roman province (which became three the principalities) was subject to the authority of an external power. Yet, despite conflict and confrontation, a rich culture emerged which blended East and West, creating a cultural bridge between rival civilizations. Nor was conflict constant. The early seventeenth century under Ottoman rule saw a period of peace and prosperity. The Rumanian legacy, which in many respects builds on that of ancient Dacia, suggests that while civilizational clash is one option, mutual enrichment and a developing consciousness that we are all members of a single human family, is another.

Notes

- ↑ Charles Matson Odahl, Constantine and the Christian Empire (London, UK: Routledge, 2004, ISBN 9780415174855).

- ↑ Heroditus, George Rawlinson (trans.), Histories: Book One "Clio," MIT Internet Classic Archive. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ↑ Horace, Clifford Herschel Moore, and Edward Parmalee Morris, Horace: The Odes and Epodes (New York, NY: American Book Co., 1902).

- ↑ Goldsworthy (2003), 322.

- ↑ Matyszak (2004), 215.

- ↑ Matyszak (2004), 216.

- ↑ Luttwak (1976), 53.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Matyszak (2004), 217.

- ↑ Matyszak (2004), 219.

- ↑ Luttwak (1976), 54.

- ↑ Goldsworthy. 2003. page 329.

- ↑ Matyszak (2004), 222.

- ↑ Matyszak (2004), 223.

- ↑ Luttwak (1976), 39.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Caesar, Julius, Anne Wiseman, and T.P. Wiseman. The Battle for Gaul. Boston, MA: D.R. Iodine, 1980. ISBN 978-0879233068

- Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith. In the Name of Rome: The Men who Won the Roman Empire. London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003. ISBN 978-0297846666

- Hoddinott, R.F. The Thracians. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1981. ISBN 978-0500020999

- Luttwak, Edward. The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire From the First Century C.E. to the Third. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0801818639

- Matyszak, Philip. The Enemies of Rome: From Hannibal to Attila the Hun. London, UK: Thames & Hudson, 2004. ISBN 978-0500251249

- Oltean, Ioana A. Dacia: Landscape, Colonisation and Romanisation. Routledge monographs in classical studies. London, UK: Rutledge, 2007. ISBN 0415412528

- Roman Archaeology Conference, W.S. Hanson, and Ian Haynes. Roman Dacia: The Making of a Provincial Society. Journal of Roman archaeology. no. 56. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 2004. ISBN 978-1887829564

External Links

All links retrieved June 23, 2022.

- Ptolemy's Geography, book III, chapter 5.

- UNRV Dacia article.

- sights.seindal.dk - Dacians as they appear on the Arch of Constantine.

- www.fectio.org.uk - Draco Late Roman military standard.

- Journey to the Land of the Cloud Rovers - photographic slide show of Sarmizegetusa. Requires Macromedia Shockwave.

- Dacia on coins.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.