Damascus Document

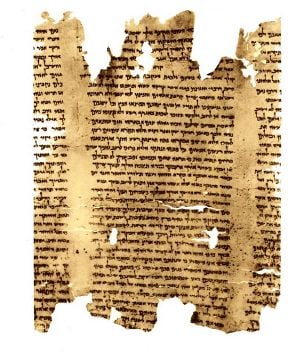

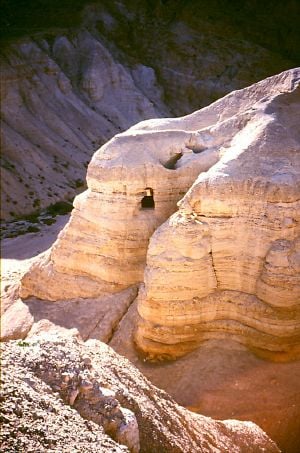

The Damascus Document, also called the Zadokite Fragments, is one of the works found in multiple fragmentary copies in the caves at Qumran, and as such is counted among the Dead Sea Scrolls. It is unique among the Qumran sectarian documents in that a copy of the work had been previously discovered near the turn of the twentieth century in Egypt.

Because it gives insights into the special religious attitudes of its writers, the Damascus Document is considered by many scholars to be one of the most important sources for understanding the ancient Essene movement. The document seems to have been written in stages between 175 B.C.E. and 70 C.E., after which the community at Qumran was abandoned.

The first section of the Damascus Document concerns the community's particular religious vision. It stresses devotion to Israel's covenant with God, the hope of the imminent coming of both a priestly and a kingly Messiah, and a strict interpretation of Jewish law. It also speaks of the community's mysterious Teacher of Righteousness and his enemy, the Man of Lies. Various theories have emerged concerning the identity and roles of these two antagonists.

The document's second section contains a set of regulations concerning community life and discipline. It gives a sense of the sect's strict religious tradition as its members—living in communities scattered throughout Israel—prepared themselves for the Messiah's coming. The document provides valuable insights into the varied religious culture of Judaism at the turn of the Common Era, including information about the reasons why the teachings of Jesus stirred opposition among many pious Jews.

History

The noted Jewish scholar Rabbi Solomon Schechter first discovered the document in the Cairo Geniza, an Egyptian synagogue storeroom containing hundreds of long forgotten manuscripts. He studied and published it under the title of the Zadokite Fragments in 1910. Schechter assigned it this name on account of several references to the Israelite priest Zadok, to whom the sect that produced the document looked as a model of faithfulness. Although the two copies Schechter worked from were medieval, he believed the original must have been ancient, from around the first century B.C.E. The discovery of several additional fragments of the document at Qumran in 1947-48 proved Schechter correct.

In contrast to the fragments found at Qumran, the Cairo documents are largely complete, and therefore vital for reconstructing the text. Eight separate copies of the Damascus Document were kept in Qumran Cave 4 and an additional copy in Cave 5. These fragments have been dated to the beginning of the Common Era, give or take several decades. Where the content of the Qumran documents overlaps with the Geniza manuscripts, there is little variation between them.

The current title of the document comes from several references within it to a community of the "new covenant" in Damascus. It is a matter of debate whether this is a literal reference to Damascus in Syria, a metaphorical reference to a great pagan city (similar to "Babylon" in the Book of Revelation), or possibly even Qumran itself.

Contents

The Damascus Document consists of two distinct parts: a sermon designed to inspire faithfulness among community members, and a set of rules setting forth some of the community's moral, religious, and legal standards. The second part of the document is sometimes called the "Community Rule," but should not be confused with another important document often given that title and sometimes called the Manual of Discipline or the Qumran community's "charter."

A call to righteousness

The Geniza versions of the Damascus Document begin with an exhortation to righteousness and speak of the origins of the document's sacred community. It prominently mentions a Teacher of Righteousness and calls on the community to adhere strictly to the standards of purity he established. Against this is set the evil teachings of the equally mysterious Man of Mockery (Lies). God is forgiving of those who sin if they change their ways, but "great wrath in flames of fire" are reserved for those who rebel without repentance.

The text speaks of avoiding three fundamental snares of Belial (Satan): fornication, lust for wealth, and defiling the Temple. It equates the taking of two wives with fornication, declaring that: "The Principle of Creation is 'male and female he created them.'" Equally condemned is the practice of defiling the sacred sanctuary, specifically by failing to separate the "clean from the unclean" and by lying sexually with a women during her menstrual period.

It stresses the need for holiness in several other matters as well: avoiding the misuse of offerings and abusing Temple funds, distinguishing between the sacred and the profane, refraining from defrauding wealthy widows, and keeping the Sabbath strictly according to the "new covenant in the land of Damascus." One must love one's brother as oneself, support the poor and needy, and give aid to aliens and strangers.

The document speaks with hope of the coming of a Messiah of Aaron and of Israel. It quotes Numbers 24:7 "A star has left Jacob, a staff has risen from Israel," which it explains as referring to "the Interpreter of the Law," the leader of Israel who will destroy its enemies with the sword.

A substantial part of the discourse is devoted to the need to shun the promptings of one's own "willful heart." The dictates of the Teacher of Righteousness must be upheld and those of the Man of Lies must be rejected. Those who repent, even after having failed to keep the "sure covenant they made in the land of Damascus," will be forgiven. They will ultimately prevail over the "men of mockery" and all of the inhabitants of the earth.

Disciplinary rules

Many of the rules set down in the second part of the Damascus Document are repetitions and expansions on laws found in the Torah and are thus in the general tradition of Jewish halakha. However, a number of them give insights in the unique character of the Qumran community, generally thought to be an Essene group.[1] The document, however, is clearly intended for a broader community than the Qumran community alone, as it refers to numerous covenant groups of various sizes living in cities and camps.

Among its more interesting rules are:

- No swearing, either by Lamedh (the initial consonant of Elohim) or by "Aleph" and "Daleth," (Referring to Adonai, the Lord).

- "Only the enemies of God take vengeance."

- Lost property whose owner is unknown belongs to the priests.

- No gleaning of fields on the Sabbath.

- No carrying of medicines on the Sabbath.

- No using tools on the Sabbath, such as ropes or ladders, to help people who have fallen into bodies of water, even if they may drown as a result.

- "A man may not lie with a woman in the city of the Temple..."

- No commerce with Gentiles involving items or food that might be used for idolatry (such as the sale of potential sacrificial animals, wine, metals, or related implements).

- No business should be conducted even with Jews if they are known to be corrupt.

- Seating and speaking in community meetings is strictly according to ranks: priests, Levites, Israelites, and proselytes.

- Priests must master a document called the "Book of Meditation." The head priest of each camp or community must be at least 36 years of age.

- Minor violations of discipline may be punished by reduction of rations, exclusion from community meals, or temporary expulsion from the community.

- Major violations, namely slander and "proving unfaithful to the truth," are to be punished by an expulsion of two years.

- Fornication is grounds for permanent expulsion.

- Transgressors who have been expelled must be cursed and shunned.

The above laws are implemented as a temporary measure during the current "era of wickedness" until the coming of the Messiah of Aaron and the Messiah of Israel.

Significance

The Damascus Document sheds a great deal of light on the character of its particular community, as well as the context in which earliest Christianity arose in first century Judaism. If it is indeed an Essene document, as the majority of scholars think, it gives important details about the Essene movement, its devotion to its beloved Teacher of Righteousness, and its commitment to a strict standard of religious discipline. The document also shows that the Essene movement had chapters in several cities, as well as a number of camps. Each camp had its own "overseer" who served as its teacher, spiritual guide, preacher, and pastor.

The attitude of the Damascus Document also shows why certain Jews at the time of Jesus would object to some of his teachings. Many of the teachings of Jesus opposed by the "Pharisees" and others in the New Testament were not yet settled matters of Jewish law at the time. However, commerce with Gentiles and association with corrupt Jews ("sinners")—two of the practices condemned by Jesus' opponents—are specifically prohibited in the Damascus Document. The document likewise condemns gleaning or even strolling in the fields on the Sabbath—as well as certain forms of healing or helping people—again putting it directly at odds with the teachings of Jesus.

At the same time, there are definite commonalities between the Damascus Document and the tradition taught by Jesus: no swearing, a strict teaching against adultery and fornication, an urgent sense of the imminent Messianic age, a condemnation of those who seek wealth first instead of God's will, and the promise of a fiery damnation for those who fail to repent.

If John the Baptist was an Essene preacher, as many scholars believe, the Damascus Document may give an insight into the reported differences between John's disciples and Jesus' disciples over such issues as fasting. It also may hint at the reason that the ascetic John never himself joined Jesus and apparently harbored doubts about his Messiahship (Matthew 11:2). Issues such as hand-washing, Sabbath observance, and keeping oneself away from the corrupting company of sinners and Gentiles were essential to the Qumran group. If John the Baptist shared their view, it would be difficult for him to give up his tradition of purity for the broader way that Jesus taught and practiced.

The Damascus Document may also provide an insight into the reason John felt he must speak out against the marriage of Herod Antipas to his brother's former wife, Herodias. The Damascus Document (Col. 5:9) stresses the Mosaic law's prohibitions against consanguinity. This issue may thus have been such a matter of principle for John that he risked certain arrest to speak out about it, even though this meant sacrificing his freedom to testify publicly to Jesus.

Notes

- ↑ Some recent scholarship doubts that the Dead Sea Scrolls should be associated with the Qumran community, arguing that they were deposited in the nearby caves by scribes fleeing from Jerusalem c. 70 C.E.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brosohi, Magen. The Damascus Document Reconsidered. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1992. ISBN 978-9652210142

- Davies, Philip R. The Damascus Covenant: An Interpretation of the "Damascus Document". Journal for the study of the Old Testament, 25. Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, Dept. of Biblical Studies, University of Sheffield, 1983. ISBN 978-0905774503

- Hultgren, Stephen. From the Damascus Covenant to the Covenant of the Community: Literary, Historical, and Theological Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Studies on the texts of the Desert of Judah, v. 66. Leiden: Brill, 2007. ISBN 978-9004154650

- Schechter, S., and Anan ben David. Documents of Jewish Sectaries. The Library of Biblical studies. New York: Ktav Pub. House, 1970. ISBN 978-0870680168

- Wacholder, Ben Zion. The new Damascus document: the midrash on the eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls: reconstruction, translation and commentary. Studies on the texts of the desert of Judah, v. 56. Leiden: Brill, 2007. ISBN 9004141081

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.