Declaration of Independence (United States)

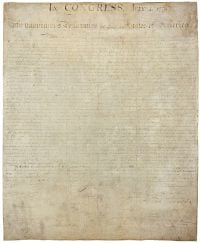

The Declaration of Independence is the document in which the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain in North America declared themselves independent of the Kingdom of Great Britain and explained their justifications for separation. It was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. This anniversary is celebrated as Independence Day in the United States. The handwritten copy signed by the delegates and given to the Congress is on display in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

The Declaration is a watershed event not only in American history, but in the history of freedom and democracy. Its most famous statement, "We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness," expresses not only the founding ethos of the United States, but established a precedent that would be used later in other struggles for freedom, including the struggle for civil rights in the United States.

History

Background

Throughout the 1750s and 1760s, relations between Great Britain and thirteen of her North American colonies became increasingly strained. Fighting broke out in 1775 at Battles of Lexington and Concord, marking the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. Although there was little initial sentiment for outright independence, the view of the British as oppressors widened after the passage of the Intolerable Acts, which struck strongly against colonial self-rule. The rising tide against British rule was exemplified and strengthened by works such as Thomas Paine's pamphlet Common Sense, first released on January 10, 1776, which had a substantial impact on the hearts and minds of colonial Americans.

Draft and adoption

On June 11, 1776, a committee consisting of John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut (the "Committee of Five"), was formed to draft a suitable declaration to frame this resolution. The committee decided that Jefferson would write the draft, which he showed to Franklin and Adams, who made several minor corrections. Jefferson then produced another copy incorporating these changes, and the committee presented this copy to the Continental Congress on June 28, 1776.

Independence was declared on July 2, 1776, pursuant to the "Lee Resolution" presented to the Continental Congress by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia on June 7, 1776, which read (in part):

"Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."

The full Declaration was rewritten somewhat in general session prior to its adoption by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, at Independence Hall. Word of the declaration reached London on August 10.

Distribution and copies

John Trumbull's famous painting is usually incorrectly identified as a depiction of the signing of the Declaration. What the painting actually depicts is the five-man drafting committee presenting their work to the Congress. Trumbull's painting can also be found on the back of the U.S. Two dollar bill.[1]

After its adoption by Congress on July 4, a handwritten draft signed by President of Congress John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson was sent to the printing shop of John Dunlap, a few blocks away. Through the night between 150 and 200 copies were made, now known as "Dunlap broadsides." One was sent to George Washington on July 6, who had it read to his troops in New York on July 9. The Declaration was read aloud for the first time publicly to those assembled in front Independence Hall in Philadelphia on July 8, 1776. The 25 Dunlap broadsides still known to exist are the oldest surviving copies of the document. The original handwritten copy has not survived.

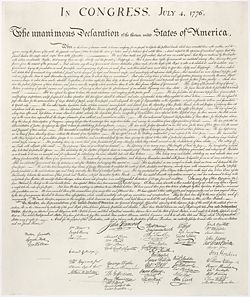

On July 19, 1776, Congress ordered a handwritten copy be produced for the delegates to sign. This engrossed copy of the Declaration was produced by Timothy Matlack, assistant to the secretary of Congress. Most of the delegates signed it on August 2, 1776, in geographic order of their colonies from north to south, though some delegates were not present and had to sign later. Two delegates never signed at all. As new delegates joined the Congress, they were also allowed to sign. A total of 56 delegates eventually signed the Declaration.

The first and most famous signature on the engrossed copy was that of John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress. Two future presidents, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, were among the signatories. Edward Rutledge (age 26), was the youngest signer, and Benjamin Franklin (age 70) was the eldest. The 56 signers of the Declaration represented the new states as follows:

- New Hampshire: Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew Thornton

- Massachusetts: Samuel Adams, John Adams, John Hancock, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry

- Rhode Island: Stephen Hopkins, William Ellery

- Connecticut: Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott

- New York: William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis Morris

- New Jersey: Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham Clark

- Pennsylvania: Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross

- Delaware: Caesar Rodney, George Read, Thomas McKean

- Maryland: Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll

- Virginia: George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson, Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton

- North Carolina: William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John Penn

- South Carolina: Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward, Jr., Thomas Lynch, Jr., Arthur Middleton

- Georgia: Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton

On January 18, 1777, the Continental Congress ordered that the declaration be more widely distributed. The second printing was made by Mary Katharine Goddard. The first printing had included only the names John Hancock and Charles Thomson. Goddard's printing was the first to list all signatories.

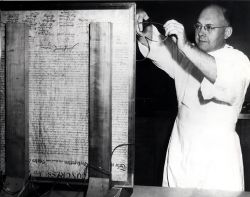

In 1823, printer William J. Stone was commissioned by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to create an engraving of the document essentially identical to the original. Stone's copy was made using a wet-ink transfer process, where the surface of the document was moistened, and some of the original ink transferred to the surface of a copper plate which was then etched so that copies could be run off the plate on a press. Because of poor conservation of the 1776 document through the nineteenth century, Stone's engraving, rather than the original, has become the basis of most modern reproductions.[2]

Annotated text of the Declaration

The text of the Declaration of Independence can be divided into five sections: the introduction, the preamble, the indictment of George III, the denunciation of the British people, and the conclusion. (Note that these five headings are not part of the text of the document.)

Introduction

In CONGRESS, July 4, 1776.

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America,

When, in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume, among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the Causes which impel them to the Separation.

Preamble

We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.

That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Prudence indeed, will dictate, that Governments long established, should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security.

Indictment

Such has been the patient Sufferance so these Colonies; and such is now the Necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The History of the Present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let the Facts be submitted to a candid World.

The signers then list 27 grievances against the British Crown. The grievances are directed personally at the King (as in “He has refused his Assent to Laws…"), although many of them refer to actions taken by the British Parliament or the Royal Governors. Many of the grievances are examples of violations of fundamental English law, such as "imposing taxes on us without our Consent," and "depriving us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury." Many historians maintain that some of the grievances are exaggerated for purposes of propaganda (such as the "Swarms of Officers" in truth referring to about 50 men ordered to prevent smuggling); the Founders probably felt that these were valid claims against the King in favor of independence.

In every stage of these Oppressions we have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble Terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated Injury. A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People.

Denunciation

Nor have we been wanting in Attentions to our British Brethren. We have warned them from Time to Time of Attempts by their Legislature to extend an unwarrantable Jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the Circumstances of our Emigration and Settlement here. We have appealed to their native Justice and Magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the Ties of our common Kindred to disavow these Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence. They too have been deaf to the Voice of Justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the Necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends.

Conclusion

The signers assert that (since conditions exist under which people must change their government, and the British have produced such conditions) the colonies must necessarily throw off political ties with the British Crown and become independent states. The conclusion contains, at its core, the Lee Resolution that had been passed on July 2.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in GENERAL CONGRESS, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which INDEPENDENT STATES may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of the divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Differences between draft and final versions

The Declaration went through three stages from conception to final adoption:

- Jefferson's original draft.[3]

- Jefferson's draft with revisions from Franklin and Adams.[4] This was the document submitted by the Committee of Five to the Congress.

- The final version, which included changes made by the full Congress.[5]

Jefferson's original draft included a denunciation of the slave trade ("He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither."), which was later edited out by Congress, as was a lengthy criticism of the British people and parliament. According to Jefferson:

The pusillanimous idea that we had friends in England worth keeping terms with, still haunted the minds of many. For this reason those passages which conveyed censures on the people of England were struck out, lest they should give them offense.[5]

Analysis

Historical influences

The United States Declaration of Independence was influenced by the 1581 Dutch Republic declaration of independence, called the Oath of Abjuration. The Kingdom of Scotland's 1320 Declaration of Arbroath was undoubtedly also an influence as the first known formal declaration of independence. Jefferson is also thought to have drawn on the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which had been adopted in June 1776.

Philosophical background

The Preamble of the Declaration is influenced by Enlightenment philosophy, including the concepts of natural law, self-determination, and Deism. Ideas and even some of the phrasing were taken directly from the writings of English philosopher John Locke, particularly his Second Treatise on Government, titled "Essay Concerning the true original, extent, and end of Civil Government." In this treatise, Locke espoused the idea of government by consent based on the Enlightenment belief that human beings were born with certain natural rights.

Locke helped to provide both the American and the French revolutionaries with intellectual ammunition for their respective causes. As a product of the Enlightenment, he did not argue so much for democracy as for a social contract between the governors and the governed. This contract could exist between citizens and monarchies or oligarchies, and not just with elected leaders. In Locke's “contract,” the governed agreed to surrender certain freedoms they enjoyed under the state of nature in exchange for the order and protection provided by a state, exercised according to the rule of law. However, if the state overstepped its limits and began to exercise arbitrary power, it essentially abrogated the contract and thus, the contract was null and void. Under those circumstances the citizens not only have the right to overthrow the state, but are indeed morally compelled to revolt and replace the state.

Other influences included the Discourses of Algernon Sydney, and the writings of Wawrzyniec Grzymala Goslicki and Thomas Paine. According to Jefferson, the purpose of the Declaration was "not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of…but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take."

Purpose

The document served several purposes. It attempts to establish clear reasons for the American's rebellion that might persuade reluctant colonists to join them as well as establish their just cause to foreign governments that might lend them aid. The Declaration also served to unite the members of the Continental Congress. Most were aware that they were signing what would be their death warrant in case the Revolution failed, and the Declaration served to make anything short of victory in the Revolution unthinkable. (Or, as Benjamin Franklin wryly noted: "We must all now hang together, or we will all surely hang separately.")

Influence on other documents

The Declaration of Independence contains many of the founding fathers' fundamental principles, some of which were later codified in the United States Constitution. It was the model for the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention Declaration of Sentiments. It has also been used as the model of a number of later documents such as the declarations of independence of Vietnam and Rhodesia. In the United States, the Declaration has been frequently quoted in political speeches, such as Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address and Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

Myths

Several myths surround the document:

- Because it is dated “July 4, 1776,” many people believe it was signed on that date—it was signed on August 2, 1776, by most of the delegates.

- An unfounded legend states that John Hancock signed his name so large that King George III would be able to read it without his spectacles. In point of fact, other examples of his signature indicate that he typically signed his name in this way.[6] Since Hancock was the first to sign the Declaration, he had the largest area in which to sign his name, which might be another reason for his signature’s large size.

- The famous painting by John Trumbull, which hangs in the Grand Rotunda of the United States Capitol Building, is (as mentioned in the caption above) usually incorrectly described as the signing of the Declaration, when what it actually shows is the five-man drafting committee presenting their work. Trumbull depicts most of the eventual signers as being present on this occasion, but this gathering never took place.

- The Liberty Bell was not rung to celebrate independence, but to call the local inhabitants to hear the reading of the document on July 8, and it certainly did not acquire its crack on that occasion; that story comes from a children's book of fiction, Legends of the American Revolution, by George Lippard. The Liberty Bell was actually named in the early nineteenth century when it became a symbol of the anti-slavery movement.

Notes

- ↑ Key to Declaration of Independence. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ↑ The Declaration of Independence—William J. Stone Engraving Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ↑ Professor Julian Boyd's reconstruction of Thomas Jefferson's "original Rough draught" Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ↑ The Papers of Thomas Jefferson contains an analysis of changes made by Franklin and Adams. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jefferson's autobiography contains a collation of the Committee draft and the final version adopted by Congress. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ↑ David Mikkelson, John Hancock on His Declaration of Independence Signature. Snopes, July 30, 2001. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bailyn, Bernard (ed.). The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti-federalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters during the Struggle for Ratification. Part One: September 1787 to February 1788. The Library of America, 1993. ISBN 0940450429

- Bailyn, Bernard (ed.). The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti-federalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters during the Struggle for Ratification. Part Two: January to August 1788. The Library of America, 1993. ISBN 094045064X

- The complete text of the Declaration of Independence at AmericanRevolution.com. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- The Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence at TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

External links

All links retrieved July 26, 2022.

- Declaration of Independence at the National Archives

- The Declaration of Independence, available for free via Project Gutenberg

- The Declaration of Independence with images, Jefferson's account, biographies of signers, and extensive additional information.

- Declaration of Independence and related resources at the Library of Congress

- The Preservation and History of the Declaration from PBS/NOVA

- "Teaching the Declaration of Independence" from ERIC Digest

- "Declaration of Independence" from the book Thrilling Incidents in American History

- "The Speech of the Unknown" from the book Washington and His Generals: or, Legends of the Revolution by George Lippard, published in 1847

- Free audiobook of The Declaration of Independence from LibriVox

- The Price They Paid – Sorting Fact from Fiction.

- Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/250px-Declaration_of_Independence_draft_(detail_with_changes_by_Franklin).jpg)