Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes (June 12, 1892 – June 18, 1982) was an American writer who played an important part in the development of twentieth century English language modernist writing by women and was one of the key figures in 1920s and 1930s bohemian Paris, after filling a similar role in the Greenwich Village of the 1910s. Her novel, Nightwood, became a cult work of modern fiction, helped by an introduction by T.S. Eliot. It stands out today for its portrayal of lesbian themes and its distinctive writing style. Since Barnes's death, interest in her work has grown and many of her books are back in print. Barnes' life and work has achieved iconic status among feminists and the homosexual community for its topics. The bohemians were among the first to promote the Sexual Revolution and the counter-cultural lifestyle, the costs of which could be argued to have outweighed the benefits.

Life

Early life (1892-1912)

Barnes was born in a log cabin in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York.[1] Her paternal grandmother, Zadel Turner Barnes, was a writer, journalist, and Women's Suffrage activist who had once hosted an influential literary salon. Her father, Wald Barnes (Barnes's father was born Henry Aaron Budington but used a variety of names during his life, including Wald Barnes and Brian Eglington Barnes),[2] was an unsuccessful composer, musician, and painter. An advocate of polygamy, he married Barnes's mother, Elizabeth, in 1889; his mistress, Fanny Clark, moved in with them in 1897, when Djuna was five. They had eight children, whom Wald made little effort to support financially. Zadel, who believed her son was a misunderstood artistic genius, struggled to provide for the entire family, supplementing her diminishing income by writing begging letters to friends and acquaintances.[3]

As the second oldest child, Barnes spent much of her childhood helping care for siblings and half-siblings. She received her early education at home, mostly from her father and grandmother, who taught her writing, art, and music, but neglected subjects such as math and spelling.[4] She claimed to have had no formal schooling at all; some evidence suggests that she was enrolled in public school for a time after age ten, though her attendance was inconsistent.[5]

At the age of 16, she was raped, apparently by a neighbor, with the knowledge and consent of her father, or possibly by her father himself. She referred to the rape obliquely in her first novel, Ryder. and more directly in her furious final play, The Antiphon. Sexually explicit references in correspondence from her grandmother, with whom she shared a bed for years, suggest incest, but Zadel—dead for forty years by the time the The Antiphon was written—was left out of its indictments.[6] Shortly before her eighteenth birthday, she reluctantly "married" Fanny Clark's brother Percy Faulkner in a private ceremony without benefit of clergy. He was fifty-two. The match had been strongly promoted by her father and grandmother, but she stayed with him for no more than two months.[7]

New York (1912-1920)

In 1912, Barnes's family, facing financial ruin, split up. Elizabeth moved to New York City with Barnes and three of her brothers, then filed for divorce, freeing Wald to marry Fanny Clark.[8] The move gave Barnes an opportunity to study art formally; she attended the Pratt Institute for about six months, but the need to support herself and her family—a burden that fell largely on her—soon drove her to leave school and take a job as a reporter and illustrator at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Over the next few years, she worked for almost every newspaper in New York, writing interviews, features, theatrical reviews, and a variety of news stories. She was fired by the Hearst Newspapers when she would not write a story about a teenage girl who had been raped by ten men; she gained entry to the girl's hospital room on a pretext, but then refused to divulge the results of the interview.

In 1915, Barnes moved out of her family's flat to an apartment in Greenwich Village, where she entered a thriving Bohemian community of artists and writers. Among her social circle were Edmund Wilson, Berenice Abbott, and the Dada artist and poet, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, whose biography Barnes tried to write but never finished. She also came into contact with Guido Bruno, an entrepreneur and promoter who published magazines and chapbooks out of his garret on Washington Square. Bruno had a reputation for unscrupulousness, and was often accused of exploiting Greenwich Village residents for profit—he used to charge tourists admission to watch Bohemians paint—but he was a strong opponent of censorship and was willing to risk prosecution by publishing Barnes's 1915 collection of "rhythms and drawings," The Book of Repulsive Women. Remarkably, despite a description of sex between women in the first poem, the book was never legally challenged; the passage seems explicit now, but at a time when lesbianism was virtually invisible in American culture, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice may not have understood its imagery.[9] Others were not as naive, and Bruno was able to cash in on the book's reputation by raising the price from fifteen to fifty cents and pocketing the difference.[10] Twenty years later, she used him as one of the models for Felix Volkbein in Nightwood, caricaturing his pretensions to nobility and his habit of bowing down before anyone titled or important.[11]

The poems in The Book of Repulsive Women show the strong influence of late nineteenth century Decadence, and the style of the illustrations resembles Aubrey Beardsley's. The setting is New York City, and the subjects are all women: A cabaret singer, a woman seen through an open window from the elevated train, and, in the last poem, the corpses of two suicides in the morgue. The book describes women's bodies and sexuality in terms that have indeed struck many readers as repulsive, but, as with much of Barnes's work, the author's stance is ambiguous. Some critics read the poems as exposing and satirizing cultural attitudes toward women.[12] Barnes herself came to regard The Book of Repulsive Women as an embarrassment; she called the title "idiotic," left it out of her curriculum vitae, and even burned copies. But since the copyright had never been registered, she was unable to prevent it from being republished, and it became one of her most reprinted works.[13]

During her Greenwich Village years, Barnes was a member of the Provincetown Players, an amateur theatrical collective whose emphasis on artistic rather than commercial success meshed well with her own values. The Players' Greenwich Village theater was a converted stable with bench seating and a tiny stage; according to Barnes, it was "always just about to be given back to the horses." Yet it played a significant role in the development of American drama, featuring works by Susan Glaspell, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Wallace Stevens, and Theodore Dreiser, as well as launching the career of Eugene O'Neill. Three one-act plays by Barnes were produced there in 1919 and 1920; a fourth, The Dove, premiered at Smith College in 1925, and a series of short closet dramas were published in magazines, some under Barnes's pseudonym, Lydia Steptoe. These plays show the strong influence of the Irish playwright John Millington Synge; she was drawn to both the poetic quality of Synge's language and the pessimism of his vision. Critics have found them derivative, particularly those in which she tried to imitate Synge's Irish dialect, and Barnes may have agreed, since in later years she dismissed them as mere juvenilia.[14] Yet, in their content, these stylized and enigmatic early plays are more experimental than those of her fellow playwrights at Provincetown.[15] A New York Times review by Alexander Woollcott of her play, Three From the Earth, called it a demonstration of "how absorbing and essentially dramatic a play can be without the audience ever knowing what, if anything, the author is driving at…. The spectators sit with bated breath listening to each word of a playlet of which the darkly suggested clues leave the mystery unsolved."[16]

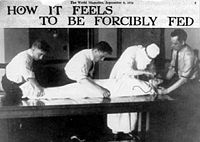

Much of Barnes's journalism was subjective and experiential. Writing about a conversation with James Joyce, she admitted to missing part of what he said because her attention had wandered, though she revered Joyce's writing. Interviewing the successful playwright, Donald Ogden Stewart, she shouted at him for "roll[ing] over and find[ing] yourself famous" while other writers continued to struggle, then said she wouldn't mind dying—an extraordinary end to the interview.[17] For a 1914 World Magazine article, she submitted to force-feeding, a technique then being used on hunger-striking suffragists. Barnes wrote "If I, play acting, felt my being burning with revolt at this brutal usurpation of my own functions, how they who actually suffered the ordeal in its acutest horror must have flamed at the violation of the sanctuaries of their spirits." She concluded "I had shared the greatest experience of the bravest of my sex". Yet, in other stories, she mocked suffrage activists as superficial, as when she quoted Carrie Chapman Catt as admonishing would-be suffrage orators never to "hold a militant pose," or wear "a dress that shows your feet in front."[18]

Barnes first published her fiction in 1914, in the pulp magazine, All-Story Cavalier Weekly; she later wrote stories and short plays for the New York Morning Telegraph's Sunday supplement. These early stories were written quickly for deadlines, and Barnes herself regarded them as juvenilia, but they anticipate her mature work in their emphasis on description and in their unusual and sometimes elaborate metaphors.[19]

Barnes was bisexual, and had relationships with both men and women during her years in Greenwich Village. In 1914, she was engaged to Ernst Hanfstaengl, then a publisher of art prints and friend of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Hanfstaengl broke up with her in 1916, apparently because he wanted a German wife.[20] He later returned to Germany and became a close associate of Adolf Hitler. From approximately 1917 until 1919, she lived with Courtenay Lemon, whom she referred to as her common-law husband, although the two never married. She was, for a time, the lover of Jane Heap, who later became co-editor of The Little Review.[21] She also had a passionate romantic relationship with Mary Pyne, a reporter for the New York Press and fellow member of the Provincetown Players. Pyne died of tuberculosis in 1919, attended by Barnes until the end.[22]

Paris (1920-1930)

In 1920, Barnes moved to Paris on an assignment for McCall's magazine. She arrived with letters of introduction to Ezra Pound and James Joyce, and she soon entered the Parisian world of expatriate bohemians who were at the forefront of the modernist movement in literature and art. Her circle included Mina Loy, Kay Boyle, Robert McAlmon, Natalie Barney, and Peggy Guggenheim. Pound disliked Barnes and her writing, but she developed a close literary and personal friendship with Joyce, who discussed his work with Barnes more freely than he did with most other writers, allowing her to call him Jim, a name otherwise only used by his wife, Nora Barnacle. She was also promoted by Ford Madox Ford, who published her work in his Transatlantic Review magazine.

She may have had a short affair with writer Natalie Barney, although she denied this;[23] the two remained friends throughout their lives. She worked for a time on a biography of the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, though it was never finished. When the Baroness fell into poverty, Djuna convinced Natalie Barney and others to help fund a flat for her in Paris.

Barnes published a collection of prose and poetry, called A Book, in 1923. In 1928, she published a semi-autobiographical novel in a mock-Elizabethan style, Ryder, which became a bestseller in the United States. She also anonymously published a satirical roman à clef of Paris lesbian life called Ladies Almanack, that same year.

In 1922, Barnes moved in with the "great love" of her life,[24] Thelma Ellen Wood, a sculptor and silverpoint artist. Although their first few years together were joyful,[25] Barnes wanted monogamy, while Wood, as Barnes later wrote, wanted her "along with the rest of the world."[26] Wood also had an increasing dependence on alcohol, and Barnes would go from café to café searching for her, "often ending up as drunk as her quarry."[27] They separated in 1928, after Wood began a relationship with heiress Henriette McCrea Metcalf (1888-1981).

Later life (1930-1982)

Barnes left Paris in 1930, and lived for a time in both London and New York. In the summers of 1932 and 1933, she stayed at Peggy Guggenheim's rented country manor, Hayford Hall, along with diarist Emily Coleman, writer Antonia White, and critic John Ferrar Holms. Much of her novel, Nightwood, was written during these summers.

She returned to Paris briefly in 1937, to sell the apartment that she and Wood had shared. In 1940, she moved to a small apartment at 5 Patchin Place in Greenwich Village, where she lived until her death. Her neighbors included the poet, E.E. Cummings.

In 1958, she published her verse play, The Antiphon. It was translated into Swedish by Karl Ragnar Gierow and U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld and was staged in Stockholm, in 1962.

The Seal, she lounges like a bride,

Much too docile, there's no doubt;

Madame Récamier, on side,

(if such she has), and bottom out.

After The Antiphon, Barnes focused on writing poetry, which she worked and reworked, producing as many as 500 drafts. She wrote eight hours a day despite a growing list of health problems, including arthritis so severe that she had difficulty even sitting at her typewriter or turning on her desk light. Many of these poems were never finalized and only a few were published in her lifetime. In her late poetry, she began to move away from the conscious archaism of her earlier work toward what she called "a very plain straight 'put it there' manner," but her penchant for unusual words gleaned from the Oxford English Dictionary nevertheless rendered most of them obscure.[28] Her last book, Creatures in an Alphabet, is a collection of short rhyming poems whose format suggests a children's book, but even this apparently simple work contains enough allusiveness and advanced vocabulary to make it an unlikely read for a child: The entry for T quotes Blake's "The Tyger," a seal is compared to Jacques-Louis David's portrait of Madame Récamier, and a braying donkey is described as "practicing solfeggio." Creatures continues the themes of nature and culture found in Barnes's earlier work, and their arrangement as a bestiary reflects her longstanding interest in systems for organizing knowledge, such as encyclopedias and almanacs.[29]

Although Barnes had other female lovers, in her later years, she was known to claim, "I am not a lesbian, I just loved Thelma."

Barnes was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1961. She was the last surviving member of the first generation of English-language modernists when she died in New York, in 1982.

Major works

Ryder

Barnes's novel Ryder (1928) draws heavily on her childhood experiences in Cornwall-on-Hudson. It covers fifty years of history of the Ryder family: Sophia Grieve Ryder, like Zadel a former salon hostess fallen into poverty; her idle son Wendell; his wife Amelia; his resident mistress Kate-Careless; and their children. Barnes herself appears as Wendell and Amelia's daughter, Julie. The story has a large cast and is told from a variety of points of view; some characters appear as the protagonist of a single chapter only to disappear from the text entirely. Fragments of the Ryder family chronicle are interspersed with children's stories, songs, letters, poems, parables, and dreams. Like James Joyce's Ulysses—an important influence on Barnes—the book changes style from chapter to chapter, parodying writers from Chaucer to Dante Gabriel Rossetti.[30]

Both Ryder and Ladies Almanack abandon the Beardsleyesque style of her drawings for The Book of Repulsive Women in favor of a visual vocabulary borrowed from French folk art. Several illustrations are closely based on the engravings and woodcuts collected by Pierre Louis Duchartre and René Saulnier in the 1926 book, L'Imagerie Populaire—images that had been copied with variations since medieval times.[31] The bawdiness of Ryder's illustrations led the U.S. Postal Service to refuse to ship it, and several had to be left out of the first edition, including an image in which Sophia is seen urinating into a chamberpot and one in which Amelia and Kate-Careless sit by the fire knitting codpieces. Parts of the text were also expurgated. In an acerbic introduction, Barnes explained that the missing words and passages had been replaced with asterisks so that readers could see the "havoc" wreaked by censorship. A 1990 Dalkey Archive edition restored the missing drawings, but the original text was lost with the destruction of the manuscript in World War II.[32]

Ladies Almanack

Ladies Almanack (1928) is a roman à clef about a predominantly lesbian social circle centering on Natalie Clifford Barney's salon in Paris. It is written in an archaic, Rabelaisian style, with Barnes's own illustrations in the style of Elizabethan woodcuts.

Barney appears as Dame Evangeline Musset, "who was in her Heart one Grand Red Cross for the Pursuance, the Relief and the Distraction, of such Girls as in their Hinder Parts, and their Fore Parts, and in whatsoever Parts did suffer them most, lament Cruelly."[33] "[A] Pioneer and a Menace" in her youth, Dame Musset has reached "a witty and learned Fifty;"[34] she rescues women in distress, dispenses wisdom, and upon her death is elevated to sainthood. Also appearing pseudonymously are Elisabeth de Gramont, Romaine Brooks, Dolly Wilde, Radclyffe Hall, and her partner Una, Lady Troubridge, Janet Flanner and Solita Solano, and Mina Loy.[35]

The obscure language, inside jokes, and ambiguity of Ladies Almanack have kept critics arguing about whether it is an affectionate satire or a bitter attack, but Barney herself loved the book and reread it throughout her life.[36]

Nightwood

Barnes's reputation as a writer was made when Nightwood was published in England in 1936, in an expensive edition by Faber and Faber, and in America in 1937, by Harcourt, Brace and Company, with an added introduction by T.S. Eliot.

The novel, set in Paris, in the 1920s, revolves around the lives of five characters, two of whom are based on Barnes and Wood, and it reflects the circumstances surrounding the ending of their real-life love affair. Wood, feeling she was wrongly represented, cut all ties with Barnes over the novel, and Barnes was said to have been comfortable with never speaking to her again. In his introduction, Eliot praises Barnes' style, which while having "prose rhythm that is prose style, and the musical pattern which is not that of verse, is so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it."

Due to concerns about censorship, Eliot edited Nightwood to soften some language relating to sexuality and religion. An edition restoring these changes, edited by Cheryl J. Plumb, was published by Dalkey Archive Press in 1995.

Legacy

Barnes has been cited as an influence by writers as diverse as Truman Capote, William Goyen, Isak Dinesen, John Hawkes, Bertha Harris, and Anais Nin. Dylan Thomas described Nightwood as "one of the three great prose books ever written by a woman," while William S. Burroughs called it "one of the great books of the twentieth century."

Bibliography

- The Book of Repulsive Women: 8 Rhythms and 5 Drawings (1915)

- A Book (1923)—revised versions published as:

- A Night Among the Horses (1929)

- Spillway (1962)

- Ryder (1928)

- Ladies Almanack (1928)

- Nightwood (1936)

- The Antiphon (1958)

- Selected Works (1962)—Spillway, Nightwood, and a revised version of The Antiphon

- Vagaries Malicieux: Two Stories (1974)—unauthorized publication

- Creatures in an Alphabet (1982)

- Smoke and Other Early Stories (1982)

- I Could Never Be Lonely without a Husband: Interviews by Djuna Barnes (1987)—ed. A. Barry

- New York (1989)—journalism

- At the Roots of the Stars: The Short Plays (1995)

- Collected Stories of Djuna Barnes (1996)

- Poe's Mother: Selected Drawings (1996)—ed. and with an introduction by Douglas Messerli

- Collected Poems: With Notes Toward the Memoirs (2005)—ed. Phillip Herring and Osias Stutman

Notes

- ↑ Herring, xvi-xxiii.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 4.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 5-21.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, xviii.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 40.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, xvi-xvii, 54-57, 268-271.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, xxiv, 59-61.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 40-41.

- ↑ Field, 65-76.

- ↑ Herring and Stutman, 43.

- ↑ Field, 77-78.

- ↑ Benstock, 240-241.

- ↑ Hardie.

- ↑ Herring, 118-126.

- ↑ Larabee, 37.

- ↑ Field, 90.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 96-101.

- ↑ Green, 82.

- ↑ Herring, 84-87.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 66-73.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 127.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 73-74.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 150.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 156.

- ↑ Weiss, 154.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 160.

- ↑ Herring, Djuna, 161.

- ↑ Levine, 186-200.

- ↑ Casselli, 89-113.

- ↑ Ponsot, 94-112.

- ↑ Burke, 67-79.

- ↑ Martyniuk, 61-80.

- ↑ Barnes, Ladies Almanack, 6.

- ↑ Barnes, Ladies Almanack, 34, 9.

- ↑ Weiss, 151-153.

- ↑ Barnes, xxxii-xxxiv.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnes, Djuna. Ladies Almanack. New York: New York University Press, 1992. ISBN 0814711804

- Broe, Mary Lynn. Silence and Power: A Reevaluation of Djuna Barnes. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1991. ISBN 0809312557

- Burke, Carolyn. "'Accidental Aloofness': Barnes, Loy, and Modernism." In Broe, Silence and Power, 67-79. 1991.

- Caselli, Daniela. "'Elementary, my dear Djuna': Unreadable simplicity in Barnes's Creatures in an Alphabet." Critical Survey. 13(3): 89-113.

- Espley, Richard. "'Something so fundamentally right': Djuna Barnes's Uneasy Intersections with Margaret Sanger and the Rhetoric of Reform." U.S. Studies Online.

- Green, Barbara. "Spectacular Confessions: 'How it Feels to Be Forcibly Fed.'" Review of Contemporary Fiction. 13(3): 82.

- Herring, Phillip. Djuna: The Life and Work of Djuna Barnes. New York: Penguin Books, 1995. ISBN 0140178422

- Herring, Phillip. "Introduction." In Barnes, Djuna. Collected Poems: With Notes Toward the Memoirs. University of Wisconsin Press, 2005. ISBN 0299212343

- Levine, Nancy J. "Works in Progress: The Uncollected Poetry of Barnes's Patchin Place Period." The Review of Contemporary Fiction 13(3): 186-200.

- Martyniuk, Irene. "Troubling the 'Master's Voice': Djuna Barnes's Pictorial Strategies." Mosaic (Winnipeg). 31(3): 61-80.

- Messerli, Douglas. "The Newspaper Stories of Djuna Barnes." In Barnes, Djuna. 1988. Smoke and Other Early Stories. Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Press, 1988. ISBN 1557130140

- Mills, Eleanor. Journalistas: 100 Years of the Best Writing and Reporting by Women Journalists. Carroll & Graf, 2005. ISBN 0786716673

- Ponsot, Marie. "A Reader's Ryder." In Broe, Silence and Power, 94-112. 1991

- Scott, Bonnie Kime. Refiguring Modernism Volume 2: Postmodern Feminist Readings of Woolf, West, and Barnes. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995. ISBN 025321002X

- Weiss, Andrea. Paris Was a Woman: Portraits From the Left Bank. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1995. ISBN 0062513133

External links

All links retrieved October 17, 2017.

- The Book of Repulsive Women

- "The Confessions of Helen Westley" — an interview.

- "What Do You See, Madam?" — one of Barnes's early newspaper short stories.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.