Dubrovnik

| Dubrovnik | |||

| Dubrovnik viewed from the Adriatic Sea | |||

|

|||

| Nickname: Pearl of the Adriatic, Thesaurum mundi | |||

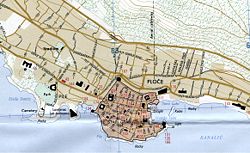

| 1995 map of Dubrovnik | |||

| The location of Dubrovnik within Croatia | |||

| Coordinates: 42°38′N 18°06′E | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Croatia | ||

| County | Dubrovnik-Neretva county | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Andro Vlahušić (CPP) | ||

| Area | |||

| - City | 21.35 km² (8.2 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2011)[1] | |||

| - City | 42,641 | ||

| - Urban | 28,113 | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 20000 | ||

| Area code(s) | 020 | ||

Dubrovnik, formerly Ragusa, is a city on the Adriatic Sea coast in the extreme south of Croatia, positioned at the terminal end of the Isthmus of Dubrovnik. Regarded as the most picturesque city on the Dalmatian coast, it is commonly referred to as the "Pearl of the Adriatic."

It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations on the Adriatic, a seaport, and the center of Dubrovnik-Neretva county.

The prosperity of the city is based on maritime trade. In the Middle Ages, as the Republic of Ragusa, it was the only eastern Adriatic city-state to rival Venice. Supported by wealth and skilled diplomacy, the city achieved a remarkable level of development, particularly during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. As a tributary of the Ottoman Sultan, it received protection that sustained its liberty and position as a major center of trade between the Ottoman Empire and Europe. Ragusa was one of the centers of Croatian language, literature, and scientific development and was home to many notable poets, playwrights, painters, mathematicians, physicists, and scholars.

The city's decline began gradually, following a shipping crisis and catastrophic earthquake in 1667 that killed more than 5,000 citizens and leveled many public buildings. However, the city managed to preserve many Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque churches, monasteries, palaces, and fountains. Dubrovnik earned designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. When it was damaged in the 1990s through occupation by the Yugoslav People's Army, it became a focus of major restoration work coordinated by UNESCO.

Geography

The name Dubrovnik originates from the Proto-Slavic term for an oak forest *dǫbrava or *dǫbrova (dubrava in archaic and literary Croatian), which was abundantly present in the hills north of the walled city of Dubrovnik by the end of the eleventh century.

Positioned at the end of the Isthmus of Dubrovnik, the city juts into the sea under the bare limestone Mount Srđ.

The Dubrovnik Region has a typical Mediterranean climate, with mild, rainy winters and hot, dry summers. However, the Bora wind blows uncomfortably cold gusts down the Adriatic coast between October and April, and thundery conditions are common all year round. In July, daytime maximum temperatures reach 84°F (29°C), and in January drop to 54°F (12°C). Mean annual precipitation is 51 inches (1298 mm).

A striking feature of Dubrovnik are the walls that run 1.2 miles (2 km) around the city, that reach a height of about 80 feet (25 meters), and run from 13 to 20 feet (four to six meters) thick on the landward side but are much thinner on the seaward side. The system of turrets and towers were intended to protect the vulnerable city now make one of the most picturesque sights in the Adriatic.

The plan of the old city, which is a maze of picturesque streets, dates from 1292. The main street, known either as Stradun or Placa, is lined with Renaissance houses, and runs along a once marshy valley. A fourteenth century Franciscan convent guards the western gate, while a Dominican convent stands by the eastern gate. The fifteenth century late Gothic Rector’s Palace was the seat of government of the Dubrovnik Republic.

History

Roman refugees fleeing the Slav and Avar sack of nearby Epidaurus, today's Cavtat, founded Ragusa (Raugia) about 614 C.E. on a rocky peninsula named Laus, the location of an ancient port. Some time later, a settlement of Slavic people grew at the foot of the forested Mount Srđ, using the name Dubrava. From that time, Dubrovnik was under Byzantine Empire protection.

The strip of wetland between Ragusa and Dubrava was reclaimed in the 12th century, unifying the city around the newly made plaza, which is today called Placa or Stradun. After the Crusades, Ragusa/Dubrovnik came under the sovereignty of Venice (1205–1358).

As a port located on overland trade routes to Byzantium and the Danube region, trade flourished. The Republic of Ragusa adopted Statutes, as early as 1272, which codified Roman practice and local customs, and provided for town planning. By the Peace Treaty of Zadar in 1358, Ragusa became part of the Hungaro-Croatian reign, although the local nobility continued to rule with little interference from Buda.

The city was ruled by aristocracy that formed two city councils and maintained a strict system of social classes. A medical service was introduced in 1301, the first pharmacy (still working) was opened in 1317, and a refuge for old people was opened in 1347. The city’s first quarantine hospital (Lazarete) was opened in 1377, the orphanage was opened in 1432, and the water supply system (20 kilometers) was constructed in 1436.

The city-state's wealth was partly the result of the land it developed, but especially of the seafaring trade it did. Ragusa's merchants traveled freely, and the city had a huge fleet of merchant ships, trading and sailing under a white flag with the word freedom (Latin: Libertas) prominently featured on it. That flag was adopted when slave trading was abolished in 1418.

In 1458, the Republic of Ragusa signed a treaty with the Ottoman Empire which made it a tributary of the sultan. The treaty protected Dubrovnik’s liberty and maintained trade between the Ottoman Empire and Europe. Skillful maneuvering such as this between East and West enabled the people of Dubrovnik to preserve their city-republic for centuries.

The South Slav language was introduced into literature, which flourished, along with art, in the 15th to 17th centuries, earning Ragusa the title of “the South Slav Athens.” The city-state offered asylum to people from all nations. Many Conversos (Marranos or Sephardic Jews) were attracted to the city. In May 1544, a ship landed there filled with Portuguese refugees.

Ragusa gradually declined after a shipping crisis, and especially a catastrophic earthquake in 1667 that killed over 5,000 citizens, including the rector, and leveled most public buildings. In 1699, the republic sold two patches of territory to the Ottomans to avoid being the location of a battlefront with advancing Venetian forces. Today this strip of land belongs to Bosnia and Herzegovina as its only direct access to the Adriatic.

In 1806, the city surrendered to French forces to cut a month-long siege by Russian-Montenegrin fleets, during which 3,000 cannonballs fell on the city. In 1808, Marshal Marmont abolished the republic and integrated its territory into the Illyrian provinces.

The Habsburg Empire gained these provinces after the 1815 Congress of Vienna, and installed a new administration which retained the essential framework of the Italian-speaking system. In that year, the Ragusan noble assembly met for the last time in the ljetnikovac in Mokošica.

In 1848, the Croatian Assembly (Sabor) published People's Requests seeking the unification of Dalmatia with the Austro-Hungarian Kingdom of Croatia. The Dubrovnik municipality was the most outspoken of all Dalmatian communes in its support for unification with Croatia. With fall of Austria-Hungary in 1918 after World War I (1914-1918), the city was incorporated into the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). The name of the city was officially changed from Ragusa to Dubrovnik.

In World War II (1939-1945), Dubrovnik became part of the Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia, occupied by an Italian army first, and by a German army after September 1943. In October 1944, Josip Broz Tito's partisans entered Dubrovnik, and sentenced approximately 78 citizens to death without trial, including a Catholic priest. Dubrovnik became part of the Communist Yugoslavia.

In 1991, Croatia and Slovenia, which at that time were republics within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, declared independence, and the Socialist Republic of Croatia was renamed the Republic of Croatia.

On October 1, 1991, the city was attacked by the Yugoslav People's Army with a siege of Dubrovnik that lasted for seven months. The heaviest artillery attack happened on December 6, when 19 people were killed and 60 wounded. In total, according to the Croatian Red Cross, 114 civilians were killed, including the celebrated poet Milan Milisić. In May 1992, the Croatian Army liberated Dubrovnik and its surroundings, but the danger of sudden attacks by the JNA lasted another three years. General Pavle Strugar, who was coordinating the attack on the city, was sentenced to an eight year prison term by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia for his role in the attack.

Government

Croatia is a parliamentary democracy in which the president is chief of state, and is elected by popular vote for a five-year term, and is eligible for a second term. The prime minister is head of government, who, as leader of the majority party, is appointed by the president and approved by the assembly. The unicameral assembly, or Sabor, comprises 153 members elected from party lists by popular vote to serve four-year terms.

Dubrovnik is the administrative center of Dubrovnik-Neretva county, which is one of Croatia's 20 counties (županijas). Dubrovnik-Neretva county is divided into five cities and 17 municipalities, and the county assembly comprises 41 representatives. Counties are regional self-government units with limited responsibility for education, health service, area and urban planning, economic development, traffic, and traffic infrastructure.

In Croatia, municipalities and towns are local self-government units responsible for housing, area and urban planning, public utilities, child care, social welfare, primary health services, education and elementary schools, culture, physical education and sports, customer protection, protection and improvement of the environment, fire protection, and civil defense.

Economy

Croatia's economic fortunes began to improve in 2000, led by a rebound in tourism and credit-driven consumer spending. A high unemployment rate (of 11.8 percent in 2007), a growing trade deficit, and uneven regional development pose challenges. Tourism and the port are the basis of Dubrovnik's economy, and there are some light industries. Croatia's per capita GDP was estimated at US$15,500 in 2007.

Rail lines connect Dubrovnik directly to neighboring countries. Dubrovnik Airport, located approximately 12 miles (20 km) from the city center, near Ćilipi, provides links to Zagreb, Croatia's capital, and European cities. Buses connect the airport with the Dubrovnik bus station. A network of modern buses connects all Dubrovnik neighborhoods. The port at nearby Gruž provides a link to other Dalmatian ports and to Italy.

Demographics

Dubrovnik's population was 43,770 in 2001,[2] down from 49,728 in 1991.[3] In the 2001 census, 88.39 percent of its citizens declared themselves as Croats.

Languages spoken include Croatian 96.1 percent, Serbian 1 percent, other and undesignated 2.9 percent (including Italian, Hungarian, Czech, Slovak, and German). The 2001 census shows that Roman Catholics made up 87.8 percent of the population of Croatia, Orthodox 4.4 percent, other Christian 0.4 percent, Muslim 1.3 percent, other and unspecified 0.9 percent, none 5.2 percent.

Dubrovnik has a number of educational institutions, including the University of Dubrovnik, a nautical college, a tourist college, a University Centre for Postgraduate Studies of the University of Zagreb, American College of Management and Technology, and an Institute of History of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Places of interest

| Old City of Dubrovnik* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv |

| Reference | 95 |

| Region** | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Extensions | 1994 |

| Endangered | 1991-1998 |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Generally regarded as the most picturesque city on the Dalmatian coast, Dubrovnik is commonly referred to as the "Pearl of the Adriatic." Though the city was severely damaged by an earthquake in 1667, it managed to preserve its beautiful Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque churches, monasteries, palaces, and fountains. It was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. When it was damaged in the 1990s through occupation and artillery attack, it became a focus of major restoration coordinated by UNESCO.

The city and its surroundings, including numerous islands, have much to attract tourists. The area boasts numerous old buildings, such as the oldest arboretum in the world, dating back to before 1492, and the third oldest European pharmacy, which dates to 1317 (and is the only one still in operation today).[4] Few of Dubrovnik's Renaissance buildings survived the earthquake of 1667 but fortunately enough remain to give an idea of the city's architectural heritage. These include:

- The Sponza Palace, which dates from the 16th century, the finest Renaissance highlight, and is used to house the National Archives.

- The Rector's Palace, which is a Gothic-Renaissance structure that displays finely carved capitals and an ornate staircase, and houses a museum.

- The Saint Saviour Church, which is a remnant of the Renaissance period, next to the much-visited Franciscan Monastery. Over the entrance is a sculpture of the Pieta that dates from the late-Gothic period. The Cloister has a colonnade of octagonal columns.

- Saint Blaise's Church, which was built in the eighteenth century in honor of Dubrovnik's patron saint, is the city's most beloved church.

- Dubrovnik's baroque Cathedral, which was built in the eighteenth century, houses an impressive Treasury with relics of Saint Blaise.

- The Dominican Monastery, which resembles a fortress on the outside but whose interior contains an art museum and a Gothic-Romanesque church.

- The round tower of the Minčeta Fortress, which was completed in 1464, is located just outside the city walls and stands atop a steep cliff. Originally designed for defense against enemies from the west, it is now used for stage plays during the summer.

The annual Dubrovnik Summer Festival is a cultural event in which keys of the city are given to artists who entertain for an entire month with live plays, concerts, and games. A holiday on February 3 each year is the feast of Sveti Vlaho (Saint Blaise), the city's patron saint, which is celebrated with Mass, parades, and festivities that last for several days.

Looking to the future

Dubrovnik has a rich heritage in which it was a prosperous city state that achieved a remarkable level of development, particularly during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when as Ragusa, it was the center of Croatian language and literature. Once the home to notable poets, playwrights, painters, mathematicians, physicists and other scholars, Dubrovnik is now a small town, although it remains a glittering draw to tourists from around the world.

Images

Notes

- ↑ Central Bureau of Statistics, 2011 Census First Results Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ↑ City of Dubrovnik, City of Dubrovnik. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ↑ A&E Television Networks, Dubrovnik.

- ↑ Dubrovnik Online, The Magic of Dubrovnik. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carter, Francis W. Dubrovnik (Ragusa): A Classic City-State. London: Seminar Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0128129500

- Everyman Mapguides. Dubrovnik. London: Everyman, 2007. ISBN 978-1841592626

- Harris, Robin. Dubrovnik: A History. London: Saqi, 2003. ISBN 978-0863563324

- Insight Pocket Guide. Dubrovnik. Singapore: APA, 2006. ISBN 978-9812583222

- Kremenjas-Danicic, Adriana. Roland's European Paths. Dubrovnik: Europski dom Dubrovnik, 2006.

- McKelvie, Robin, and Jenny McKelvie. Dubrovnik & the Dalmatian Coast. London: DK, 2006. ISBN 978-0756615536

- Stuard, Susan Mosher. A State of Deference: Ragusa/Dubrovnik in the Medieval Centuries. Middle Ages series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0812231786

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Old City of Dubrovnik. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- World Fact Book. Croatia. 2008.

External links

All links retrieved October 7, 2017.

- Dubrovnik picture gallery Croatia-official.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.