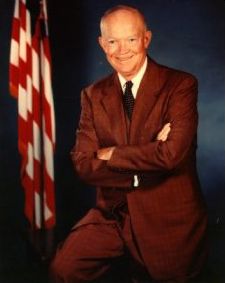

Dwight D. Eisenhower

| Term of office | January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961 |

| Preceded by | Harry S. Truman |

| Succeeded by | John F. Kennedy |

| Date of birth | October 14, 1890 |

| Place of birth | Denison, Texas |

| Date of death | March 28, 1969 |

| Place of death | Washington DC |

| Spouse | Mamie Doud Eisenhower |

| Political party | Republican |

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the highest ranking American military officer during World War II and the 34th President of the United States. During the war he served as Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe with the rank of General of the Army, and in 1949 he became the first supreme commander of NATO.

Although a military officer, Eisenhower was also deeply committed to peace. Prior to taking office as president, Eisenhower worked to bring North and South Korea to a negotiated truce to conclude the Korean War in 1953.

During his two terms, Eisenhower oversaw an increase in U.S. conventional and atomic weaponry in the global confrontation with the communist Soviet Union. During the height of the Cold War, Eisenhower sought to counter Soviet expansionism yet rejected military intervention in Vietnam despite communist takeover in the North.

Eisenhower had little tolerance for racial bigotry and ordered the complete desegregation of America's armed forces. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down laws that segregated schools in the U.S. South and in 1957 Eisenhower ordered federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to uphold the Court's ruling.

Due in some measure to Eisenhower's stature as a wartime leader and his moderate policies as president, the United States was the strongest, most influential, and most productive nation in the world when he left office in 1961. In retirement Eisenhower devoted his efforts to maintaining peace in international relations.

Early life and family

Dwight Eisenhower was born in Denison, Texas, the third of seven sons born to David Jacob Eisenhower and Ida Elizabeth Stover, and their only child born in Texas. He was named David Dwight and was called Dwight. Later, the order of his given names was switched (according to the Eisenhower Library and Museum, the name switch occurred upon Eisenhower's matriculation at West Point). The Eisenhower family is of German descent (Eisenhower) and came from the Lorraine region of France but had lived in America since the eighteenth century. The family moved to Abilene, Kansas, in 1892 and Eisenhower graduated from Abilene High School in 1909.

When Eisenhower was five years old, his parents became followers of the Watch Tower Society, whose members later took the name Jehovah's Witnesses. The Eisenhower home served as the local meeting hall from 1896 to 1915, but he and his brothers also stopped associating regularly after 1915. In later years, Eisenhower became a communicant in the Presbyterian Church, and in his retirement he was a member of the Gettysburg Presbyterian Church.[1]

Eisenhower married Mamie Geneva Doud (1896–1979), of Denver, Colorado, on July 1, 1916. They had two children, Doud Dwight Eisenhower (1917–1921), whose tragic death in childhood haunted the couple, and John Sheldon David Doud Eisenhower (born 1922). John Eisenhower served in the United States Army, then became an author and served as U.S. Ambassador to Belgium. John's son, David Eisenhower, after whom Camp David, the presidential retreat located in Maryland, is named, married Richard Nixon's daughter Julie Nixon in 1968.

Early military career

Eisenhower enrolled at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, in June 1911. Although his parents were pacifists, they were strong proponents of education and did not object to his entering West Point the military academy. Eisenhower was a strong athlete, and he was on the football team. He played against the legendary Jim Thorpe in the game against the Carlisle Indians, succeeding in tackling him but then being injured when Thorpe avoided a tackle by Eisenhower and his partner. A week later Eisenhower twisted his knee during the game against Tufts University and then further injuring the weakened knee during a riding drill, ending his football career.[2]

Eisenhower graduated in 1915 near the bottom of his class, surprisingly, since he went on to achieve the military's highest rank. He served with the infantry until 1918 at various camps in Texas and Georgia. During World War I, Eisenhower became the No. 3 leader of the new tank corps and rose to Lieutenant Colonel in the National Army. He spent the war training tank crews in Pennsylvania and never saw combat. After the war Eisenhower reverted to his regular rank of Captain and was shortly promoted to Major before assuming duties at Camp Meade, Maryland, where he remained until 1922. His interest in tank warfare was strengthened by many conversations with George S. Patton and other senior tank leaders; however their ideas on tank warfare were strongly discouraged by superiors.[3]

Eisenhower became executive officer to General Fox Conner in the Panama Canal Zone, where he served until 1924. Under Conner's tutelage, he studied military history and theory (including Carl von Clausewitz's On War) and acknowledged Conner's enormous influence on his military thinking. In 1925-1926, he attended the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and then served as a battalion commander at Fort Benning, Georgia, until 1927.

Eisenhower returned to the U.S. in 1939 and held a series of staff positions in Washington, D.C., California, and Texas. In June 1941, he was appointed Chief of Staff to General Walter Krueger, Commander of the 3rd Army, at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, and promoted to Brigadier-General in September 1941. Although his administrative abilities had been noticed, on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II he had never held an active command and was far from being considered as a potential commander of major operations.

World War II

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was assigned to the General Staff in Washington, where he served until June 1942 with responsibility for creating the major war plans to defeat Japan and Germany. He was appointed Deputy Chief in charge of Pacific Defenses under the Chief of War Plans Division, General Leonard T. Gerow, and then succeeded Gerow as Chief of the War Plans Division. Then he was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff in charge of Operations Division under Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. It was his close association with Marshall that finally brought Eisenhower to senior command positions. Marshall recognized his great organizational and administrative abilities.

In 1942, Eisenhower was appointed Commanding General, European Theater of Operations (ETOUSA) and was based in London. In November, he was also appointed Supreme Commander Allied (Expeditionary) Force of the North African Theater of Operations (NATOUSA). The word "expeditionary" was dropped soon after his appointment for security reasons. In February 1943, his authority was extended across the Mediterranean basin to include the British 8th Army, commanded by General Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein. The 8th Army had advanced across the Western Desert in North Africa from the east and was ready for the start of the Tunisia Campaign. Eisenhower gained his fourth star and gave up command of ETOUSA to be commander of NATOUSA. After the capitulation of Axis forces in North Africa, Eisenhower remained in command of the renamed Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO), keeping the operational title and continued in command of NATOUSA redesignated MTOUSA. In this position he oversaw the invasion of Sicily and the invasion of the Italian mainland.

In December 1943, Eisenhower was named Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. In January 1944, he resumed command of ETOUSA and the following month was officially designated as the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), serving in a dual role until the end of hostilities in Europe in May 1945. In these positions he was charged with planning and carrying out the Allied assault on the coast of Normandy in June 1944 under the code name Operation Overlord, the subsequent liberation of Western Europe, and the invasion of Germany. A month after the Normandy D-Day on June 6, 1944, the invasion of southern France took place, and control of the forces which took part in the southern invasion passed from the AFHQ to the SHAEF. From then until the end of the war in Europe on May 8, 1945, Eisenhower through SHAEF had supreme command of all operational Allied forces, and through his command of ETOUSA, administrative command of all U.S. forces, on the Western Front north of the Alps.

As recognition of his senior position in the Allied command, on December 20, 1944, he was promoted to General of the Army equivalent to the rank of Field Marshal in most European armies. In this and the previous high commands he held, Eisenhower showed his great talents for leadership and diplomacy. Although he had never seen action himself, he won the respect of front-line commanders. He dealt skillfully with difficult subordinates such as Omar Bradley and George Patton and allies such as Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and General Charles de Gaulle. He had fundamental disagreements with Churchill and Montgomery over questions of strategy, but these rarely upset his relationships with them. He negotiated with Soviet Marshal Zhukov, and such was the confidence that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had in him, he sometimes worked directly with Stalin.

Eisenhower was offered the Medal of Honor for his leadership in the European Theater but refused it, saying that it should be reserved for bravery and valor.

It was never a certainty that Operation Overlord would succeed. The tenuousness surrounding the entire decision including the timing and the location of the Normandy invasion might be summarized by a short speech that Eisenhower wrote in advance, in case he might need it. In it, he took full responsibility for catastrophic failure, should that be the final result. Long after the successful landings on D-Day and the BBC broadcast of Eisenhower's brief speech concerning them, the never-used second speech was found in a shirt pocket by an aide. It read:

"Our landings have failed and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone."

Following Germany's unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, Eisenhower was appointed Military Governor of the U.S. Occupation Zone, based in Frankfurt-am-Main. Germany was divided into four Occupation Zones, one each for the U.S., Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. In addition, upon full discovery of the death camps that were part of the Final Solution of the Holocaust, he ordered camera crews to comprehensively document evidence of the atrocity so as to prevent any doubt of its occurrence. He made the controversial decision to reclassify German prisoners of war (POWs) in U.S. custody as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs). As DEFs, they could be compelled to serve as unpaid conscript labor. Although an unknown number may have died in custody as a consequence of malnutrition, exposure to the elements, and lack of medical care, losses were small when compared to the numbers of prisoners lost under Soviet, German and even French control.[4]

Eisenhower was an early supporter of the Morgenthau Plan which would have placed Germany's main industrial areas under international governance and turned over most land to agriculture. In November 1945 he approved the distribution of one thousand free copies of Henry Morgenthau's, book Germany is our problem, which promoted and described the plan in detail, to American military officials in occupied Germany.[5]

He had grave misgivings about President Harry S. Truman's decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan.[6]

Eisenhower served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army from 1945-1948. In December 1950, he was named Supreme Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and given operational command of NATO forces in Europe. Eisenhower retired from active service on May 31, 1952, upon entering politics. He wrote Crusade in Europe, widely regarded as one of the finest U.S. military memoirs. During this period Eisenhower served as president of Columbia University from 1948 until 1953, though he was on leave from the university while he served as NATO commander.

Presidential Years 1953-1961

After his many wartime successes, General Eisenhower returned to the U.S. a great hero. Not long after his return, a "Draft Eisenhower" movement in the Republican Party persuaded him to declare his candidacy in the 1952 presidential election to counter the candidacy of isolationist Senator Robert A. Taft. He refused to stand but supporters entered his name in the primaries, and he started to win. 'I like Ike' campaign badges became popular among his supporters and Eisenhower eventually asked to be relieved of his command in order to run for the presidency. He defeated Taft for the Republican nomination but came to an agreement that Taft would stay out of foreign affairs while Eisenhower followed a conservative domestic policy.

Eisenhower's campaign was a crusade against the Truman administration's prosecution of the Korean War. Eisenhower promised to go to Korea himself and both end the war and maintain a strong NATO presence abroad against Communism. He and his running mate Richard Nixon defeated Adlai Stevenson in a landslide, marking the first Republican return to the White House in 20 years and the only military general to serve as U.S. President in the twentieth century.

Foreign policy

On November 29, 1952 U.S. President-elect Dwight D. Eisenhower fulfilled a campaign promise by traveling to Korea to learn what could be done to end the conflict. Eisenhower visited American soldiers on the front lines and revived the stalled peace talks. Eight months after his return, in July 1953, with the UN's acceptance of India's proposal for a ceasefire, the Korean armistice was signed, formalizing the status of the two Koreas. The agreement separated the two countries at roughly the same border that existed prior to the war and created a demilitarized zone at the 38th parallel. No peace treaty has been signed to date.

With the death of Stalin there was talk of some sort of détente with the Soviet Union. Eisenhower brought Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to tour the U.S. in 1959, but a planned reciprocal visit was canceled by the Soviets after they shot down an American spy plane (the U-2 Crisis of 1960). Eisenhower was thus the first US Cold War President to meet with a Soviet leader, a move that many Republicans opposed. In 1954, the French implored Eisenhower to send the U.S. Navy to rescue Vietnam from communist advances in the north. Eisenhower refused, and acquiesced in the division of Vietnam into a Communist North and a South informally allied with the United States, and sent a few hundred advisers. However, he did not want to get embroiled in a war in distant Southeast Asia just after the stalemated Korean War, and containment seemed better than a confrontation with an uncertain outcome.

He believed that 'detente and co-existence' rather than confrontation was the best policy. He also was concerned with the way in which the defense industry drained material and intellectual resources from the civil sector.[6] "Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed," Eisenhower said in 1953. "This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children."

In his influential "atoms for peace" speech at the UN General Assembly in 1953, Eisenhower said that nuclear technology “must be put into the hands of those who will know how to strip its military casing and adapt it to the arts of peace.” This historic address helped initiate research and development to apply nuclear technology for civilian use and the loan of American uranium to underdeveloped nations for peaceful purposes.[7]

Eisenhower Doctrine

In 1956-1957 following Egypt's nationalization of the Suez Canal, and the ensuing conflict between Britain, France, Israel and Egypt, Eisenhower persuaded Britain, France, and Israel to withdraw, avoiding an almost inevitable clash with the Soviet Union. After the Suez Crisis, the United States became the protector of most Western interests in the Middle East. As a result, Eisenhower felt the need to announce that the United States, in relation to the Middle East, would be "prepared to use armed force… [to counter] aggression from any country controlled by international communism." This was one of Eisenhower's contributions to the Cold War, in which a series of third-world countries would become surrogates, or backdrops, for friction in the standoff between the United States and Soviet Union. In July 1958, the U.S. sent 14,000 Marines to Lebanon to put down a rebellion against a pro-Western government. He also allowed the CIA to 'overthrow the government of Guatemala' in a 1954 coup against President Jacobo Arbenz Guzman (1913-1971) who was suspected of Communist leanings.

Domestic policy

Throughout his presidency, Eisenhower preached a doctrine of dynamic conservatism. Although he maintained a rigorously conservative economic policy, his social policies were fairly liberal. While he worked to reduce the size of government, contain inflation, and lower taxes, he simultaneously created the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, joined Congress in raising minimum wage from 75 cents to $1 per hour, and extended Social Security benefits to 10 million more Americans. His cabinet consisted of many corporate executives and some labor leaders, called by one journalist "Eight millionaires and a plumber." As a result, Eisenhower was extremely popular, winning his second term with 457 of the 530 votes in the Electoral College, and 57.6 percent of the popular vote.[8]

Interstate highway system

One of Eisenhower's lesser known but most important acts as president was championing the construction of the modern day Interstate highway system, modeled after the Autobahns that American troops had seen in Germany. Eisenhower viewed the highway system as essential to American safety during the Cold War; a means of quickly moving thousands of people out of cities or troops across the country was key in an era of nuclear paranoia and Soviet Union blitzkrieg invasion scenarios imagined by military strategists. It is a popular legend that Eisenhower required the Interstate Highway System to have one out of every five miles straight in case an airplane needed to make an emergency landing, or in case the highway needed to become an impromptu U.S. Air Force airport. The closest to reality this ever came was a plan to build landing strips beside highways, but the "one in five" plan was never part of the original Interstate Highway System. Today, the American Interstate highway system is the largest and most extensive in the world and allows for auto travel across large distances in half the time as without such a system.

Eisenhower and civil rights

Eisenhower has sometimes been criticized for his cautious approach to the emerging civil rights movement. Like earlier American statesmen who have been faulted for racial attitudes that seem unenlightened by contemporary standards, notably Abraham Lincoln, Eisenhower was a product of his time. Like Lincoln, Eisenhower abhorred degrading racist attitudes, racial injustice, and, particularly, violence against blacks that undermined the nation's democratic ideals. Yet, again like Lincoln, Eisenhower preferred a gradual, constitutionalist approach that would avoid disruption of society.

Following the landmark 1954 civil rights ruling Brown v. Board of Education desegregating U.S. public schools, and growing civil unrest in the South, Eisenhower recognized that the federal government had a necessary role to play. His policies consistently moved the nation toward legal and social recognition and equality of all Americans regardless of race.

Although he anticipated a moderate course from his judicial appointments and was initially dismayed with the Brown decision, Eisenhower sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce the ruling when Governor Orval Faubus openly defied a court order to integrate all-white Little Rock Central High.

Eisenhower appointed jurists to the Supreme Court as well as to Southern federal courts who were committed to equal rights, and directed the Justice Department to argue in support of desegregation in cases before the Supreme Court. Eisenhower won Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and additional voting rights legislation in 1960, which were important precedents for more comprehensive civil rights legislation in the following years.[9]

Eisenhower also ordered the integration of the U.S. armed forces. Although President Truman issued an Executive Order to desegregate the military services, Eisenhower, with the prestige of the World War II supreme commander, demanded compliance, and by October 30, 1954, the last segregated unit in the armed forces had been integrated and all federally controlled schools for military dependent children had been desegregated.

As president, Eisenhower established the first comprehensive regulations prohibiting racial discrimination in the federal workforce and also took initiative to transform the almost entirely segregated city of Washington. Though public and private actions he pressured local government administrators, motion picture executives, and businessmen to reverse the culture of segregation in Washington. By the end of his presidency the nation's capital was an almost fully integrated city.[9]

In July 1955, Eisenhower appointed Rutgers University Law School graduate E. Frederic Morrow as Administrative Officer for Special Projects, the first African-American to serve in an executive level position in the White House. Eisenhower was also the first president since Reconstruction to personally meet with black civil rights leaders. Although he was unable to build a consensus in Congress to pass major reforms, later civil rights legislation of the 1960s would not have been possible without Eisenhower's progressive presidency. Eisenhower by most estimates achieved more toward making equal treatment advanced civil rights for minority Americans more than any president since Reconstruction.[9] "There must be no second class citizens in this country," he wrote.

Retirement and death

On January 17, 1961, Eisenhower gave his final televised speech from the Oval Office. In his farewell speech to the nation, Eisenhower raised the issue of the Cold War and role of the U.S. armed forces. He described the Cold War saying:

We face a hostile ideology global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose and insidious in method… " and he warned about what he saw as unjustified government spending proposals and continued with a warning that "we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex…. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Eisenhower retired to the place where he and Mamie had spent much of their post-war time, a working farm, now a National Historic Site, adjacent to the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. In retirement, he did not completely retreat from political life; he spoke at the 1964 Republican convention and appeared with Barry Goldwater in a Republican campaign commercial from Gettysburg.[10]

Because of legal issues related to holding a military rank while in a civilian office, Eisenhower had resigned his permanent commission as General of the Army before entering the office of President of the United States. Upon completion of his Presidential terms, Eisenhower was reactivated and he again was commissioned a five-star general in the United States Army.

Eisenhower died at 12:25 P.M. on March 28, 1969, at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington D.C., of Congestive heart failure at the age of 78. He lies alongside his wife and their first child, who died in childhood, in a small chapel called the Place of Meditation, at the Eisenhower Presidential Library, located in Abilene. His state funeral was unique because it was presided over by Richard Nixon, who was Vice President under Eisenhower and was serving as President of the United States.[11]

Legacy

Eisenhower's reputation declined after leaving office and he was sometimes seen as a "do-nothing" president in contrast to his young activist successor, John F. Kennedy, but also because of his cautious stance toward the American Civil Rights Movement and the divisive McCarthy hearings. Such omissions were held against him during the liberal climate of the 1960s and 1970s. Eisenhower's reputation has risen since that time because of his non-partisan governing philosophy, his wartime leadership, his action in Arkansas, and his prudent management of the economy. Furthermore, he is remembered for ending the Korean War, avoiding military intervention in Vietnam and avoiding military confrontation during the height of the Cold War. Finally, the last two states, Alaska and Hawaii, entered the union during Eisenhower's second term. In more recent surveys of historians, Eisenhower often is ranked in the top ten among all U.S. Presidents.

Eisenhower is purported to have said that his September 1953 appointment of California Governor Earl Warren as Chief Justice of the United States was "the biggest damn fool mistake I ever made." Eisenhower disagreed with several of Warren's decisions, including Brown vs. Board of Education, although he later signed many significant civil rights bills and can be seen in hindsight as a leader in the movement to bring civil rights to all Americans.

Eisenhower's picture was on the dollar coin from 1971 to 1979 and reappeared on a commemorative silver dollar issued in 1990, celebrating the 100th anniversary of his birth. USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Nimitz-class supercarrier, was named in his honor.

In 1983, The Eisenhower Institute was founded in Washington, D.C., as a policy institute to advance Eisenhower's intellectual and leadership legacies on the public policy themes of advancing civil rights, foreign policy and building partnerships around the world, and fighting poverty.

In 1999, the United States Congress created the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission, [12] which is creating an enduring national memorial in Washington, D.C., across the street from the National Air and Space Museum on the National Mall. It provides access to all Eisenhower speeches and documents via an online searchable database.

Quotations

- Kinship among nations is not determined in such measurements as proximity of size and age. Rather we should turn to those inner things—call them what you will—I mean those intangibles that are the real treasures free men possess.

- From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city, every village, and every rural schoolhouse, the dedication of our nation and our people to the Almighty.—Dwight D. Eisenhower when signing into law the phrase "One nation under God" into the Pledge of Allegiance.

- Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. This is not a way of life at all in any true sense. Under the clouds of war, it is humanity hanging on a cross of iron.—Dwight Eisenhower, April 16, 1953

- I like to believe that people in the long run are going to do more to promote peace than our governments. Indeed, I think that people want peace so much that one of these days governments had better get out of the way and let them have it.—Dwight D. Eisenhower

- In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.—Dwight D. Eisenhower, Farewell Address January 17, 1961

- I voiced to him [Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson] my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.—Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1945 [13]

- Peace and Justice are two sides of the same coin.—Dwight D. Eisenhower [14]

Notes

- ↑ Gettysburg Presbyterian Church.Gettysburg.com.

- ↑ Carlo D'Este, Eisenhower: A Soldier's Life (Henry Holt & Co., 2002, ISBN 0805056866), 68.

- ↑ E.K.G. Sixsmith, Eisenhower as military commander. (NY: Da Capo Press, 1990), 6

- ↑ Günter Bischof and Stephen Ambrose. Eisenhower and the German PoWs: Facts Against Falsehood. (Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1992)

- ↑ John Dietrich. The Morgenthau Plan: Soviet Influence on American Postwar Policy. (NY: Algora Publishing, 2002, ISBN 1892941902), 27. Eisenhower later insisted that the free distribution did not "constitute approval or disapproval of the views expressed." Historian Stephen Ambrose concludes that "There can be little doubt, however, that at the time, Eisenhower definitively did approve, just as there can be little doubt that in the August 1944 conversation Eisenhower gave Morgenthau at least some of his ideas on the treatment of Germany." Stephen Ambrose. Eisenhower: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect. (NY: Simon & Schuster; Touchstone edition, 1991. ISBN 0671747584), 422.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 David Schoenbrun, America Inside Out. (NY: McGraw-Hill, 1984 ISBN 0070554730).

- ↑ Biography of Dwight D. Eisenhower. The White House.gov.

- ↑ Paul S. Boyer, et al. The Enduring Vision. (NY: Houghton Mifflin, 2000 ISBN 061847384X)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Eisenhower Memorial Commission Dwight D. Eisenhower and Civil Rights. Retrieved May 21, 2008

- ↑ 1964: Johnson vs Goldwater Web reference Livingroomcandidate.

- ↑ US Army website U.S. Army. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ↑ Eisenhower Memorial Commission. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- ↑ The White House Years: Mandate for Change: 1953–1956: A Personal Account

- ↑ Quote database.com. Quote DB Retrieved September 17, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources

- Boyle, Peter G. (ed.). The Churchill-Eisenhower Correspondence, 1953-1955. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990. ISBN 0807819107

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends. Eastern Acorn Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0915992041

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. Crusade in Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. ISBN 080185668X

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. The White House years. 2 vol., Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1963-1965. Mandate for change, 1953-1956. (v. 1) Waging peace, 1956-1961. (v. 2)

- Papers—Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890 - 1969), Miller Center of Public Affairs, Scripps Library & Multimedia Archive. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

Secondary sources

- Albertson, Dean (ed.). Eisenhower as President. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 1963. ASIN B003RM5EBI

- Alexander, Charles C. Holding the Line: The Eisenhower Era, 1952-1961. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1975. ISBN 0253328403

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: Soldier and President. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; Touchstone edition, 1991. ISBN 0671747584 One volume version. Standard biography.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect, 1890-1952. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1983. ISBN 0671440691

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower. The President. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1984 ISBN 0671499017

- Bischof, Günter, and Stephen Ambrose. Eisenhower and the German PoWs: Facts Against Falsehood. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge and London, 1992. ISBN 978-0807117583

- Bowie, Robert Richardson and Richard H. Immerman. Waging Peace: How Eisenhower Shaped an Enduring Cold War Strategy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0195062647

- Boyer, Paul S., et al. The Enduring Vision. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin, 2000. ISBN 061847384X

- Damms, Richard V. The Eisenhower Presidency, 1953-1961. Longman, 2002. ISBN 0582368189

- David, Paul Theodore (ed.) Presidential Nominating Politics in 1952. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1954. 5 vols. ASIN B001NIBT9O

- D'Este, Carlo. Eisenhower: A Soldier's Life. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Co., 2002 ISBN 0805056866 Military biography to 1945.

- Dietrich, John. The Morgenthau Plan: Soviet Influence on American Postwar Policy. New York, NY: Algora Publishing, 2002. ISBN 1892941902

- Divine, Robert A. Eisenhower and the Cold War. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1981. ISBN 0195028244

- Eisenhower, David. Eisenhower at War 1943-1945. New York, NY: Wings Books: Distributed by Outlet Book Co., 1991. ISBN 0517065010 detailed study by his grandson

- Greenstein, Fred I. The Hidden-Hand Presidency: Eisenhower as Leader. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994. ISBN 0801849012

- Harris, Douglas B. "Dwight Eisenhower and the New Deal: The Politics of Preemption," Presidential Studies Quarterly 27 (1997).

- Harris, Seymour E. The Economics of the Political Parties, with Special Attention to Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1962. ASIN B0000CLIHQ

- Krieg, Joann P. (ed.). Dwight D. Eisenhower, Soldier, President, Statesman. New York, NY: Greenwood Press, 1987. ISBN 0313259550 24 essays by scholars.

- McAuliffe, Mary S. "Eisenhower, the President," Journal of American History 68 (1981): 625-632.

- Medhurst, Martin J. Dwight D. Eisenhower: Strategic Communicator. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993. ISBN 0313261407

- Olson, James S. Historical Dictionary of the 1950s. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 0313306192

- Pach, Chester J., and Elmo Richardson. Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1991. ISBN 0700604375 standard scholarly survey.

- Parmet, Herbert S. Eisenhower and the American Crusades, New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1999. ISBN 0765804379 Scholarly biography of post-1945 years.

- Pogue, Forrest C. The Supreme Command. Center of Military History, United States Army, 1989. ASIN B00072KFGA official Army history of SHAEF.

- Schoenbrun, David. America Inside Out. New YOrk, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1984. ISBN 0070554730

- Sixsmith, E.K.G. Eisenhower as Military Commander. New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1990. ISBN 0306803690

- Van der Zee, Henri A. (Antony). The Hunger Winter: Occupied Holland 1944-1945. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0803296185

- Weigley, Russell Frank. Eisenhower's Lieutenants. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1981. ISBN 0253133335 Ike's dealing with his key generals in WW2.

External links

All links retrieved October 5, 2017.

- The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum

- The Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum

- First Inaugural Address, 1953

- Second Inaugural Address, 1957

- The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.