Ebionites

The Ebionites (from Hebrew; אביונים, Ebyonim, "the poor ones") were an early sect of Jewish followers of Jesus that flourished from the first to the fifth century C.E. in and around the Land of Israel.[1] In contrast to the dominant Christian sects that viewed Jesus as the incarnation of God, the Ebionites saw Jesus as a mortal human being, who by being a holy man,[2] was chosen by God to be the prophet of the "Kingdom of Heaven."[3] The Ebionites insisted on following Jewish dietary and religious laws,[4] and rejected the writings of Paul of Tarsus.[5] Thus, Ebionites were in theological conflict with the emerging dominant streams of Christianity that opened up to the Gentiles.

Scholarly knowledge of the Ebionites is limited and fragmentary, deriving primarily from the polemics of the early Church Fathers. Many scholars argue that they existed as a distinct group from Pauline Christians and Gnostic Christians before and after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 C.E., and they have been linked to the Jerusalem church of James, the brother of Jesus.[6] Some even contend that Ebionites were more faithful than Paul to the authentic teachings of Jesus.[3][7][8][1] They called themselves the 'Poor Ones' because they regarded a vow of poverty to be central to actualizing the "kingdom of God" was already on Earth.[9] Accordingly, they dispossessed themselves of all their goods and lived in religious communistic societies.[4] Their accounts at times seem to be contradictory due to the double application of the term "Ebionite," some referring to Jewish Christianity as a whole, others only to a sect within it.

Reports on the Ebionites by the Church Fathers may have exaggerated the theological difference between them and orthodox Christians due to the polemical nature of these reports and their aim to purge the church of the remnants of Jewish influence.

History

Since there is no independent archeological evidence for the existence and history of Ebionites, much of what we know about them comes from brief references to them by early and influential theologians and writers in the Christian Church, who viewed the group as "heretics" and "Judaizers." Justin Martyr, in the earliest text known to us, describes an unnamed sect estranged from the Church who observe the Law of Moses, and who hold it of universal obligation.[10] Irenaeus was the first to use the term "Ebionites" to describe a heretical Judaizing sect, which he regarded as stubbornly clinging to the Law.[5] The most complete account comes from Epiphanius of Salamis, who wrote a heresiology in the fourth century, denouncing 80 heretical sects, among them Ebionites.[11] These figures provide mostly general descriptions of their religious ideology, though sometimes there are quotations from their gospels, which are otherwise lost to us.

The Fathers of the Church distinguished between the Ebionites and the Nazarenes, another early sect of Jewish followers that thrived from around 30 to 70 C.E. It is believed that the Nazarenes were one of the earliest Christian churches in Jerusalem or, properly speaking, the first "Judeo-Christian synagogue" built on Mount Zion between 70 and 132 C.E.[12] While many Fathers of the Church differentiated between the Ebionites and the Nazarenes in their writings, Jerome clearly thinks that Ebionites and Nazoraeans were a single group.[13] Without surviving texts, it is difficult to establish exactly the basis for their distinction.

Beliefs and practices

Most historical sources agree that the Ebionites denied many of the central doctrines of mainstream Christianity such as the trinity of God, the pre-existence and divinity of Jesus, the virgin birth, and the death of Jesus as an atonement for sin.[14][4] Ebionites seemed to have emphasized the humanity of Yeshua (the Hebrew name for Jesus) as the biological son of both Mary and Joseph, who, after following John the Baptist as a teacher, became a "prophet like Moses" (foretold in Deuteronomy 18:14-22) when he was anointed with the holy spirit at his baptism.[3]

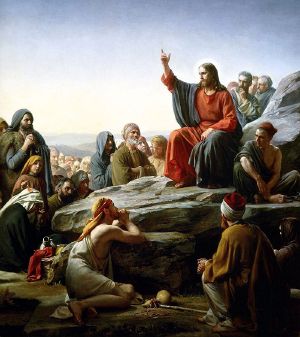

Of all the books of the New Testament, Ebionites only accepted an Aramaic version of the Gospel of Matthew, referred to as the Gospel of the Hebrews, as additional scripture to the Hebrew Bible. This version of Matthew, critics reported, omitted the first two chapters (on the nativity of Jesus), and started with the baptism of Jesus by John.[3] Ebionites understood Jesus as inviting believers to live according to an ethic that will be standard in the future kingdom of God. Since they believed that this will be the ethic of the future, Ebionites went ahead and adjusted their lives to this ethic in this age. Ebionites, therefore, believed all Jews and gentiles must observe Mosaic Law; but it must be understood through Jesus' expounding of the Law, which he taught during his Sermon on the Mount.[15] They held a form of "inaugurated eschatology" which posited that the ministry of Jesus has ushered in the Messianic Age so that the kingdom of God may be understood to be present in an incipient fashion, while at the same time awaiting consummation in the future age following the coming of the Jewish messiah, to whom Jesus was only a herald.[1]

Like traditional Jews, Ebionites may have restricted communion only to gentiles who converted to Judaism,[10] and revered Jerusalem as the holiest city.[5] Scholar James Tabor, however, argues that Ebionites rejected doctrines and traditions, which they believed had been added to Mosaic Law, including scribal alterations of the texts of scripture; and that they had a greater interest in restoring the more anarchist form of worship reflected in the pre-Mosaic period of Judaism.[1] Tabor relies on Epiphanius' description of Ebionites as rejecting parts or most of the Law, as religious vegetarians, as opposed to animal sacrifice; and his quoting of their gospel as ascribing these injunctions to a Jesus seen as the incarnation of Christ, a great archangel.[16] Scholar Shlomo Pines counters that all these teachings are "Gnostic Christian" in origin and are characteristics of the Elcesaite sect, which have been mistakenly or falsely attributed to Ebionites.[17] Without a consensus among scholars, the issue remains contentious.[18]

Ebionites regarded the Desposyni (the blood relatives of Jesus) as the legitimate apostolic successors to James the Just (the brother of Jesus), and patriarchs of the Jerusalem Church, rather than Peter.[1] Furthermore, Ebionites denounced Paul as an apostate from the Law and a false apostle. Epiphanius claims that some Ebionites gossiped that Paul was a Greek who converted to Judaism in order to marry the daughter of (Annas?) a High Priest of Israel, and then apostatized when she rejected him.[19]

Influence

The influence of Ebionites on mainstream Christianity is debated. Once the Roman army decimated the Jerusalemite leadership of the mother church of all Christendom during the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 C.E., Jewish Christians gradually lost the struggle for the claim to orthodoxy due to marginalization and persecution.[3] Scholar Hans-Joachim Schoeps, however, argues that the primary influence of Ebionites on mainstream Christianity was to aid in the defeat of gnosticism through counter-missionary work.[8] It has also been argued by writer Keith Akers that they had an influence on the origins of Islam and the Sufis.[7] Ebionites may be represented in history as the sect encountered by the Muslim historian Abd al-Jabbar (c. 1000 C.E.) almost five hundred years later than most Christian historians allow for their survival.[17] An additional possible mention of surviving Ebionite communities existing in the lands of north-western Arabia, specifically the cities of Tayma and Tilmas, around the eleventh century, is said to be in Sefer Ha'masaoth, the "Book of the Travels" of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, a Sephardic rabbi of Spain.[20] Twelfth-century historian Mohammad Al-Shahrastani, in his book Religious and Philosophical Sects, mentions Jews living in nearby Medina and Hejaz who accepted Jesus as a prophetic figure and followed normative Judaism, rejecting the christology of the Pauline Church.[21]

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, several small yet competing new religious movements, such as the Ebionite Jewish Community, have emerged claiming to be revivalists of the beliefs and practices of ancient Ebionites, although their idiosyncratic claims to authenticity cannot be verified. Like virtually all Jewish denominations, groups and national organizations, modern Ebionites charge Messianic Judaism, as promoted by controversial groups such as Jews for Jesus, to be Pauline Christianity blasphemously presenting itself as Judaism.[22]

Assessment

The differences between Ebionism and mainstream Pauline Christianity may well be over-drawn. Most of our knowledge on Ebionism may be much limited because it is based on the polemical reports made by the early Church Fathers, who had the "tendency... to exaggerate the difference between the heretics and the orthodox," and who therefore "were not generally very careful to apprehend exactly the views of those whose opinions they undertook to refute."[23] Even if the Ebionites may have disliked and ignored Paul, there is no historical evidence that they denounced him by name or attempted "to pillory him under the image of Simon Magnus." Although the Ebionites may have seen Jesus as a man, they also "had to imagine a Divine influence coming down upon him at His baptism, setting Him apart from all others." Perhaps, they were aware that the Pauline views were already quite influential and widespread.

If this reconciliatory perspective is correct, if it is also true, according to some scholars, that the Ebionites were faithful to the authentic teachings of Jesus, and also if it is factually true that Pauline Christology recognized the humanity of Christ as well as his divinity, then the gap between Ebionites and Pauline Christians has been made unnecessarily sharp.

Ebionite writings

Few writings of Ebionites have survived, and in uncertain form. The Recognitions of Clement and the Clementine Homilies, two third-century Christian works, are regarded by general scholarly consensus as largely or entirely Jewish Christian in origin and reflect Jewish Christian ideas and beliefs. These can be found in volume 8 of the Ante-Nicene Fathers. The exact relationship between Ebionites and these writings is debated, but Epiphanius's description of the Ebionites in Panarion 30 bears repeated and striking similarity to the ideas in the Recognitions and Homilies. Koch speculates that Epiphanius likely relied upon a version of the Homilies as a source document.[11]

The Catholic Encyclopedia (1908) mentions four classes of Ebionite writings:[14]

- Gospel of the Ebionites. Ebionites used only the Gospel of Matthew (according to Irenaeus). Eusebius of Caesarea (Historia Ecclesiae IV, xxi, 8) mentions a Gospel of the Hebrews, which is often identified as the Aramaic original of Matthew, written with Hebrew letters. Such a work was known to Hegesippus (according to Eusebius, Historia Eccl., ), Origen (according to Jerome, De vir., ill., ii), and Clement of Alexandria (Strom., II, ix, 45). Epiphanius of Salamis attributes this gospel to Nazarenes, and claims that Ebionites only possessed an incomplete, falsified, and truncated copy. (Adversus Haereses, xxix, 9). The question remains whether or not Epiphanius was able to make a genuine distinction between Nazarenes and Ebionites.

- New Testament apocrypha: The Circuits of Peter (periodoi Petrou) and Acts of the Apostles, amongst which is the work usually titled the Ascents of James (anabathmoi Iakobou). The first-named books are substantially contained in the Homilies of Clement under the title of Clement's Compendium of Peter's itinerary sermons, and also in the Recognitions attributed to Clement. They form an early Christian didactic fiction to express Jewish Christian views, i.e. the primacy of James, their connection with Rome, and their antagonism to Simon Magnus, as well as Gnostic doctrines. Van Voorst opines of the Ascents of James (R 1.33-71), "There is, in fact, no section of the Clementine literature about whose origin in Jewish Christianity one may be more certain."[24] Despite this assertion, he expresses reservations that the material is genuinely Ebionite in origin.

- The Works of Symmachus the Ebionite, i.e. his Greek translation of the Old Testament, used by Jerome, fragments of which exist, and his lost Hypomnemata which was written to counter the canonical Gospel of Matthew. The latter work, which is totally lost (Eusebius, Hist. Eccl., VI, xvii; Jerome, De vir. ill., liv), is probably identical with De distinctione præceptorum, mentioned by Ebed Jesu (Assemani, Bibl. Or., III, 1).

- The Book of Elchesai (Elxai), or of "The Hidden power," claimed to have been written about 100 C.E. and brought to Rome about 217 by Alcibiades of Apamea. Those who accepted its doctrines and new practices were called Elcesaites. (Hipp., Philos., IX, xiv-xvii; Epiphanius., Adv. Haer., xix, 1; liii, 1.)

It is also speculated that the core of the Gospel of Barnabas, beneath a polemical medieval Muslim overlay, may have been based upon an Ebionite document.[25] The existence and origin of this source continues to be debated by scholars.[26]

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 James D. Tabor, Ancient Judaism: Nazarenes and Ebionites. The Jewish Roman World of Jesus. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ Ante-Nicene Fathers, Hippolytus, The Refutation of All Heresies, Book 7. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Hyam Maccoby, The Mythmaker: Paul and the Invention of Christianity (New York: Harper & Row, 1987). Partial online version. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kaufmann Kohler, “Ebionites,” Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Ante-Nicene Fathers, Irenaeus, The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, 1.26.2. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ Robert Eisenman, James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls (New York: Viking, 1996).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Keith Akers, The Lost Religion of Jesus: Simple Living and Nonviolence in Early Christianity (New York: Lantern Books, 2000).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hans-Joachim Schoeps, Jewish Christianity: Factional Disputes in the Early Church, trans. Douglas R. A. Hare (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1969).

- ↑ Richard Shand, The Ministry of Jesus: The Open Secret of the Kingdom of God. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ante-Nicene Fathers, Justin Martyr (140 C.E.) "Dialogue With Trypho The Jew" xlvii (47.4).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Glenn Alan Koch, A Critical Investigation of Epiphanius' Knowdedge of the Ebionites: A Translation and Critical Discussion of 'Panarion' 30 (University of Pennsylvania, 1976).

- ↑ Bargil Pixner, “Church of the Apostles found on Mt. Zion,” Biblical Archaeological Review (May/June 1990).

- ↑ Ante-Nicene Fathers, Jerome, "Epistle to Augustine" 112.13.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 “Ebionites,” Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ Francois Viljoen, “Jesus' Teaching on the Torah in the Sermon on the Mount,” Neotestamenica 40.1 (2006): 135-155. Excerpt available online. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ Epiphanius of Salamis, The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis Book I (Sects 1-46), translated by Frank Williams (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1987), 30.14.5, 30.16.4, 30.16.5, 30.18.7-9, 30.22.4. Sections available online. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Schlomo Pines, “The Jewish Christians Of The Early Centuries Of Christianity According To A New Source,” Proceedings of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities II 13 (1966).

- ↑ A. F. J. Klijn and G. J. Reinink, Patristic Evidence for Jewish-Christian Sects (1973).

- ↑ Epiphanius, Panarion 16.9.

- ↑ Marcus N. Adler, The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela: Critical Text, Translation and Commentary (New York: Phillip Feldheim, 1907), 70-72. Available online. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ Muhammad Shahrastani, The Book of Religious and Philosphical Sects (London, 1842; Gorgias Press, 2002, ed. William Cureton), 167.

- ↑ Shemayah Phillips, “Messianic Jews: Jewish Idolatry Revisited,” Our Liberation Magazine (August /September 2006).

- ↑ Bible History Online, "Ebionism; Ebionites." Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ Robert E. Van Voorst, The Ascents of James: History and Theology of a Jewish-Christian Community (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1989).

- ↑ John Toland, Nazarenus, or Jewish, Gentile and Mahometan Christianity (1718).

- ↑ R. Blackhirst, “Barnabas and the Gospels: Was There an Early Gospel of Barnabas?” J. Higher Criticism 7(1) (Spring 2000): 1-22. Available online. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century C.E., with an Account of the Principal Sects and Heresies by Henry Wace – Christian Classics Ethereal Library

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.