Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (January 12, 1729 – July 9, 1797) was an Anglo-Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist, and philosopher, who served for many years in the British House of Commons as a member of the Whig party. He is chiefly remembered for his support of the American colonies in the struggle against King George III that led to the American Revolution and for his strong opposition to the French Revolution in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790). The latter made Burke one of the leading figures within the conservative faction of the Whig party (which he dubbed the "Old Whigs"), in opposition to the pro-revolutionary "New Whigs," led by Charles James Fox. Edmund Burke’s ideas influenced the fields of aesthetics and political theory. His early work on aesthetics, Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), explored the origins of these two fundamental concepts, relating them respectively to fear of death and to love of society. In A Vindication of Natural Society: A View of the Miseries and Evils Arising to Mankind, which appeared in 1756, he attacked social philosophy, especially that of Rousseau.

Burke was taken up by the literary and artistic circles of London, and his publisher encouraged him to try his hand at history, but his historical work was not published during his lifetime. Soon afterward he entered politics, and as a Member of Parliament he produced a number of famous political pamphlets and speeches on party politics, including Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents (1770) and his speech on Conciliation with America (1775), and on financial reform and on the reform of British India, Speech on Mr. Fox’s East India Bill (1783). Burke also founded the Annual Register, a political review. He is often regarded as the father of Anglo-American conservatism.

Life

Edmund Burke was born January 12, 1729 in Dublin, Ireland. Burke was of Munster Catholic stock, but his father, a solicitor, conformed to the Church of Ireland. His mother, whose maiden name was Nagle, belonged to the Roman Catholic Church. Burke was raised in his father's faith and remained a practicing Anglican throughout his life, but his political enemies would later repeatedly accuse him of harboring secret Catholic sympathies at a time when membership in the Catholic church would have disqualified him from public office.

He received his early education at a Quaker school in Ballitore and in 1744 he entered Trinity College in Dublin. In 1747, he founded a Debating Club, known as Edmund Burke's Club, which in 1770 merged with the Historical Club to form the College Historical Society. The minutes of the meetings of Burke's club remain in the collection of the Historical Society. He graduated in 1748. Burke's father wished him to study law, and he went to London in 1750 and entered the Middle Temple, but soon gave up his legal studies in order to travel in Continental Europe.

Burke's first published work, A Vindication of Natural Society: A View of the Miseries and Evils Arising to Mankind (1756), attacked social philosophy, especially that of Rousseau, and was fraudulently attributed to Lord Bolingbroke. It was originally taken as a serious treatise on anarchism. Years later, with a government appointment at stake, Burke claimed that it had been intended as a satire. Many modern scholars consider it to be satire, but others take Vindication as a serious defense of anarchism (an interpretation notably espoused by Murray Rothbard). Whether written as a satire or not, it was the first anarchist essay, and was taken seriously by later anarchists such as William Godwin.

In 1757 Burke published a treatise on aesthetics, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, which explored the origins of these two fundamental concepts, relating them respectively to fear of death and to love of society. The essay gave him a reputation in England and attracted the attention of prominent Continental thinkers such as Denis Diderot, Immanuel Kant, and G. E. Lessing. The following year, with the publisher Robert Dodsley, he created the influential Annual Register, a publication in which various authors evaluated the international political events of the previous year. The first volume appeared in 1758, and he retained the editorship for about thirty years.

In 1757 Burke also married Jane Nugent. During this period in London, Burke became closely connected with many of the leading intellectuals and artists, including Samuel Johnson, David Garrick, Oliver Goldsmith, and Joshua Reynolds.

Political career

At about this same time, Burke was introduced to William Gerard Hamilton (known as "Single-speech Hamilton"). When Hamilton was appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, Burke accompanied him to Dublin as his private secretary, a position he held for three years. In 1765, after an unsuccessful first venture into politics, Burke became private secretary to liberal Whig statesman Charles Watson-Wentworth, the Marquess of Rockingham, leader of one of the groups of Whigs, the largely liberal faction in Parliament, who remained Burke's close friend and associate until his premature death in 1782.

In 1765 Burke entered the British Parliament as a member of the House of Commons for Wendover, a pocket borough in the control of Lord Verney (later second Earl Verney), a close political ally of Rockingham. Burke soon became involved in the greatest domestic constitutional controversy of the reign of King George III. The question was whether the king or the Parliament should control the executive; King George III was seeking a more active role for the Crown, which increasingly had lost its influence during the reign of the first two Georges, without impinging on the limitations set on the royal prerogative by the settlement of the Revolution of 1689. Burke published Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents (1770),[1] arguing that George’s actions were against the spirit of the constitution. It was favoritism to allow the King to choose ministers purely on personal grounds; they should be selected by the Parliament with public approval. The pamphlet included Burke’s novel justification of party, which he defined as a body of men united on public principle, which could act as a constitutional link between King and Parliament, providing the administration with strength and consistency, and with principled criticism in times of opposition. Burke argued strongly against unrestrained royal power and for the role of political parties in maintaining a legitimate, organized opposition capable of preventing abuses by the monarch or by specific factions within the government.

Burke expressed his support for the grievances of the American colonies under the government of King George III and his appointed representatives. He also campaigned against the persecution of Catholics in Ireland and denounced the abuses and corruption of the East India Company.

In 1769 Burke published, in reply to George Grenville, his pamphlet on The Present State of the Nation. In the same year he purchased the small estate of Gregories near Beaconsfield. The 600–acre estate was purchased with mostly borrowed money, and though it contained an art collection that included works by Titian, Gregories nevertheless would prove to be a heavy financial burden on Burke in the following decades. His speeches and writings had now made him famous, and it was even suggested that he was the author of the Letters of Junius.

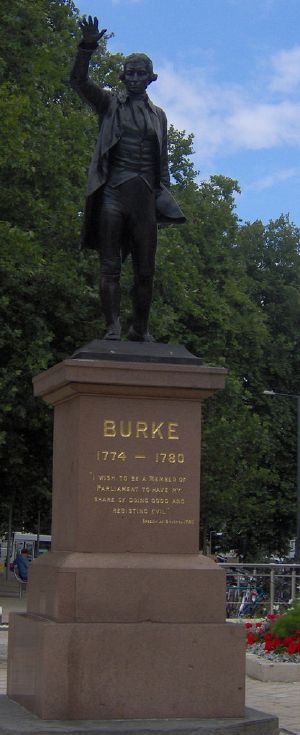

In 1774 he was elected member for Bristol, "England's second city" and a large constituency with a genuine electoral contest. His address to the electors of Bristol defended the principles of representative democracy against the notion that elected officials should act narrowly as advocates for the interests of their constituents. Burke's arguments in this matter helped to formulate the delegate and trustee models of political representation. His support for free trade with Ireland and his advocacy of Catholic emancipation were unpopular with his constituents and caused him to lose his seat in 1780. For the remainder of his parliamentary career, Burke represented Malton, North Yorkshire, another pocket borough controlled by Rockingham.

Under the Tory administration of Lord Frederick North (1770 – 1782) the American war went on from bad to worse, and it was in part owing to the oratorical efforts of Burke that the war was at last brought to an end. To this period belong two of his most famous performances, his speech on Conciliation with America (1775), and his Letter to the Sheriffs of Bristol (1777). North’s fall from power led to Rockingham being reinstated. Burke became Paymaster of the Forces and Privy Councillor, but Rockingham's unexpected death in July 1782 put an end to his administration after only a few months.

Burke then supported fellow Whig Charles James Fox in his coalition with Lord North, a decision that many came to regard later as his greatest political error. Under that short-lived coalition he continued to hold the office of Paymaster and he distinguished himself in connection with Fox's India Bill. The coalition fell in 1783, and was succeeded by the long Tory administration of William Pitt the Younger, which lasted until 1801. Burke remained in opposition for the remainder of his political life. In 1785 he made his famous speech on The Nabob of Arcot's Debts, and in the next year (1786) he moved for papers in regard to the Indian government of Warren Hastings, the consequence of which was the impeachment trial of Hastings. The trial, of which Burke was the leading promoter, lasted from 1787 until Hastings's eventual acquittal in 1794.

Response to the French Revolution

Given his record as a strong supporter of American independence and as a campaigner against royal prerogative, many were surprised when Burke published his Reflections on the Revolution in France in 1790. Burke became one of the earliest and fiercest British critics of the French Revolution, which he saw not as movement towards a representative, constitutional democracy but rather as a violent rebellion against tradition and proper authority and as an experiment disconnected from the complex realities of human society, which would end in disaster. Former admirers of Burke, such as Thomas Jefferson and fellow Whig politician Charles James Fox, denounced Burke as a reactionary and an enemy of democracy. Thomas Paine penned The Rights of Man in 1791 as a response to Burke. However, other pro-democratic politicians, such as the American John Adams, agreed with Burke's assessment of the French situation. Many of Burke's dire predictions for the outcome of the French Revolution were later borne out by the execution of King Louis XVI, the subsequent Reign of Terror, and the eventual rise of Napoleon's autocratic regime.

These events, and the disagreements which arose regarding them within the Whig party, led to its breakup and to the rupture of Burke's friendship with Fox. In 1791 Burke published his Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs, in which he renewed his criticism of the radical revolutionary programs inspired by the French Revolution and attacked the Whigs who supported them. Eventually most of the Whigs sided with Burke and voted their support for the conservative government of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, which declared war on the revolutionary government of France in 1793.

In 1794 Burke was devastated by the loss of his son Richard, of whom he was very fond. In the same year the Hastings trial came to an end. Burke, feeling that his work was done and that he was worn out, took leave of Parliament. The King, whose favor he had gained by his attitude towards the French Revolution, wished to make him Lord Beaconsfield, but the death of his son had deprived such an honor of all its attractions, and the only reward he would accept was a pension of £2,500. Even this modest reward was criticized by the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Lauderdale, to whom Burke made a crushing reply in the Letter to a Noble Lord (1796). His last publications were the Letters on a Regicide Peace (1796), in response to the negotiations for peace with France.

Burke died in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire on July 9, 1797.

Influence and reputation

| "On the one hand [Burke] is revealed as a foremost apostle of Liberty, on the other as the redoubtable champion of Authority. But a charge of political inconsistency applied to this life appears a mean and petty thing. History easily discerns the reasons and forces which actuated him, and the immense changes in the problems he was facing which evoked from the same profound mind and sincere spirit these entirely contrary manifestations. His soul revolted against tyranny, whether it appeared in the aspect of a domineering Monarch and a corrupt Court and Parliamentary system, or whether, mouthing the watch-words of a non-existent liberty, it towered up against him in the dictation of a brutal mob and wicked sect. No one can read the Burke of Liberty and the Burke of Authority without feeling that here was the same man pursuing the same ends, seeking the same ideals of society and Government, and defending them from assaults, now from one extreme, now from the other." |

| Winston Churchill, Consistency in Politics |

Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France was extremely controversial at the time of its publication. Its intemperate language and factual inaccuracies even convinced many readers that Burke had lost his judgment. But as the subsequent violence and chaos in France vindicated much of Burke's assessment, it grew to become his best-known and most influential work. In the English-speaking world, Burke is often regarded as one of the fathers of modern conservatism, and his thinking has exerted considerable influence over the political philosophy of such classical liberals as Friedrich Hayek and Karl Popper. Burke's "liberal" conservatism, which opposes the implementation of drastic theoretical plans for radical political change but recognizes the necessity of gradual reform, must not be confused with the autocratic conservatism of such anti-revolutionary Continental figures as Joseph de Maistre.

Adam Smith remarked that "Burke is the only man I ever knew who thinks on economic subjects exactly as I do without any previous communication having passed between us." The Liberal historian Lord John Dalberg-Acton considered Burke one of the three greatest liberals, along with William Ewart Gladstone and Thomas Babington Macaulay. Two contrasting assessments of Burke were offered long after his death by Karl Marx and Winston Churchill.

| ”The sycophant—who in the pay of the English oligarchy played the romantic "laudator temporis acti" against the French Revolution just as, in the pay of the North American colonies at the beginning of the American troubles, he had played the liberal against the English oligarchy—was an out-and-out vulgar bourgeois.” |

| Karl Marx, Das Kapital |

Though still controversial, Burke is today widely regarded as one of the major political thinkers of the English-speaking world. His writings, like his speeches, are characterized by their synthesis of knowledge, thought, and feeling. He was more successful as a writer than he was as a speaker. He often rose too far above the heads of his audience, who were eventually wearied, and even disgusted, by the continued splendor of his declamation, his inordinate copiousness, and his excessive vehemence, which often passed into fury. Burke was known as the "Dinner Bell" to his contemporaries because Members of Parliament would leave the chamber to look for dinner when he rose to speak. But his writings contain some of the grandest examples of a fervid and richly elaborated eloquence. Though he was never admitted to the Cabinet, he guided and strongly influenced the policy of his party. His efforts in the direction of economy and order in administration at home, and on behalf of a more just government in America, India, and Ireland, as well as his contributions to political philosophy, constitute his most significant legacy.

Burke is the namesake of a variety of prominent associations and societies, including The Antient and Honourable Edmund Burke Society at the University of Chicago.

| Preceded by: Richard Rigby |

Paymaster of the Forces 1782 |

Succeeded by: Isaac Barré |

| Preceded by: Isaac Barré |

Paymaster of the Forces 1783–1784 |

Succeeded by: William Wyndham Grenville |

Speeches

Burke made several famous speeches while serving in the British House of Commons:

- On American Taxation (1774): "Whether you were right or wrong in establishing the Colonies on the principles of commercial monopoly, rather than on that of revenue, is at this day a problem of mere speculation. You cannot have both by the same authority. To join together the restraints of an universal internal and external monopoly, with an universal internal and external taxation, is an unnatural union; perfect uncompensated slavery."

- On Conciliation with America[2] (1775): "The proposition is peace. Not peace through the medium of war; not peace to be hunted through the labyrinth of intricate and endless negotiations; not peace to arise out of universal discord fomented, from principle, in all parts of the Empire, not peace to depend on the juridical determination of perplexing questions, or the precise marking [of] the shadowy boundaries of a complex government. It is simple peace; sought in its natural course, and in its ordinary haunts. It is peace sought in the spirit of peace, and laid in principles purely pacific…"

Writings

- A Vindication of Natural Society: A View of the Miseries and Evils Arising to Mankind 1756 (Liberty Fund, 1982, ISBN 0865970092). This article, outlining radical political theory, was first published anonymously and, when Burke was revealed as its author, he explained that it was a satire. The consensus of historians is that this is correct. An alternate theory, proposed by Murray Rothbard, argues that Burke wrote the Vindication in earnest but later wished to disavow it for political reasons.

- A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful 1757, begun when he was nineteen and published when he was twenty-seven. (Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0192835807).

- Reflections on the Revolution in France 1790 (Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 0192839780). Burke's criticisms of the French Revolution and its connection to Rousseau's philosophy, made before the revolution was radicalized, predicted that it would fall into terror, tyranny, and misrule. Burke, a supporter of the American Revolution, wrote the Reflections in response to a young correspondent who mistakenly assumed that he would support the French Revolution as well. It was addressed to an anonymous French nobleman whose identity has been the subject of many rumors. Thomas Copeland, editor of Burke's Correspondence, put forth a compelling argument that the recipient was in fact Victor Marie du Pont. (Victor's brother was Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, founder of the E.I. duPont de Nemours Company.)

Quotes

- "Manners are of more importance than laws… Manners are what vex or soothe, corrupt or purify, exalt or debase, barbarize or refine us, by a constant, steady, uniform, insensible operation like that of the air we breathe in."[3]

The statement that "The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing" is often attributed to Burke. Although it has not been found in his speeches, writings, or letters (and is thus apocryphal), in 1770 he wrote in Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents that "when bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle." John Stuart Mill made a similar statement in an inaugural address delivered to the University of St. Andrews in 1867: "Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing."

Notes

- ↑ Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents. Retrieved October 29, 2008.

- ↑ On Conciliation with America. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ↑ Edmund Burke, Letters on a Regicide Peace (Liberty Fund Inc., 1999, ISBN 978-0865971677).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burke, Edmund. Letters on a Regicide Peace. Liberty Fund Inc., 1999. ISBN 978-0865971677

- Cousin, John W. Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766143481

- Dickson, David. New Foundations of Ireland: 1660–1800. Irish Academic Press, 1999. ISBN 0716526379

- Kirk, Russell. The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot. Regnery Publishing, Inc., 2001. ISBN 0895261715

- Muller, Jerry Z. The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought. Anchor Books, 2002. ISBN 0385721668

- O'Brien, Conor Cruise. The Great Melody: A Thematic Biography of Edmund Burke. University of Chicago Press, 1994. ISBN 0226616517

External links

All links retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Project Gutenberg, Edmund Burke, including his collected works in 12 volumes.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.