Eihei-ji

Eihei-ji (永平寺) is one of two main temples of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism, the largest religious denomination in Japan (by number of temples in a single legal entity). Eihei-ji is located about 15 km (9 mi) east of Fukui in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. In English, its name means "temple of eternal peace."

The founder of Eihei-ji was Eihei Dōgen who brought Sōtō Zen from China to Japan during the thirteenth century. The ashes of Dōgen and a memorial to him are in the Joyoden (the Founder's hall) at Eihei-ji.

Eihei-ji is a training monastery with more than two hundred monks and nuns in residence. Visitors to Eihei-ji may participate in the daily schedule, that involves zazen (seated meditation), chores, and chanting sutras.

History

Dōgen founded Eihei-ji in 1244 with the name Sanshoho Daibutsuji in the woods of rural Japan, quite far from the distractions of Kamakura period urban life.

In 1243, Hatano Yoshishige (波多野義重) offered to relocate Dōgen's community to Echizen province, far to the north of Kyōto. Dōgen accepted because of the ongoing tension with the Tendai community, and growing competition with the Rinzai-school.[1]

His followers built a comprehensive center for Buddhist practice there, calling it Daibutsu Temple (Daibutsu-ji, 大仏寺). While the construction work was going on, Dōgen lived and taught at Yoshimine-dera Temple (Kippō-ji, 吉峯寺), located close to Daibutsu-ji. During his stay at Kippō-ji, Dōgen "fell into a depression". This marked a turning point in his life, giving way to "rigorous critique of Rinzai Zen."[1]

In 1246, Dōgen renamed the Daibutsu Temple, calling it Eihei-ji. This name means "temple of eternal peace" (in Japanese, 'ei' means "eternal," 'hei' means "peaceful," and 'ji' means "Buddhist temple").[2][3] Remote and removed from the established centers of Buddhism, this temple became a symbol of the "center of the world" for Dogen and his followers.[4] It remains one of the two head temples of Sōtō Zen in Japan today, the other being Sōji-ji.

Dōgen spent the remainder of his life teaching and writing at Eihei-ji. In 1247, the newly installed shōgun's regent, Hōjō Tokiyori, invited Dōgen to come to Kamakura to teach him. Dōgen made the rather long journey east to provide the shōgun with lay ordination, and then returned to Eihei-ji in 1248. In the autumn of 1252, Dōgen fell ill, and when he showed no signs of recovering, he presented his robes to his main apprentice, Koun Ejō (孤雲懐弉), making him the abbot of Eihei-ji.

Sometime after Dōgen's death the abbacy of Eihei-ji became hotly disputed in rows that involved a schism now called the sandai sōron. Until 1468, Eihei-ji was not held by the current Keizan line of Sōtō, but by the line of Dōgen's Chinese disciple Jakuen.[5] After 1468, when the Keizan line took ownership of Eihei-ji in addition to its major temple Sōji-ji and others, Jakuen's line and other alternate lines became less prominent.

As Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji became rivals over the centuries, Eihei-ji made claims to bolster its authority based on the fact of Dōgen's original residence there:

Dōgen's memory has helped keep Eiheiji financially secure, in good repair, and filled with monks and lay pilgrims who look to Dōgen for religious inspiration. Eiheiji has become Dōgen's place, the temple where Dōgen is remembered, where Dōgen's Zen is practiced, where Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō is published, where it is read, and where one goes to learn Dōgen's Buddhism. As we remember Dōgen, we should also remember that remembrance is not value neutral...."[6]

The entire temple was destroyed by fire several times. During the late sixteenth century, disciples of Ikkō-shu attacked and burned the temple and surrounding buildings.[7] The temple was rebuilt in the eighteenth century. Today, the oldest standing structure dates from 1794.

Description

Today the temple grounds cover about 330,000 m² (0.13 sq mi).[8] The Butsuden (Buddha hall) main altar carries statues of the Buddhas of the Three Times: right to left, Amida Butsu (past), Shakyamuni Butsu (present), and Miroku Bosatsu (future).[9]

Among the temple's 70 structures[8] are the Sanmon (gate), Hatto (lecture hall), Sōdo (Priest's or meditation hall), Daikuin (kitchen, three stories and a basement),[9] Yokushitsu (bath) and Tosu (toilet, Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō includes a chapter on manners appropriate for the toilet. Most of his rules are still followed today.[9]) The Shōrō (belfry) holds the obon sho, the great brahman bell. The Shidoden (Memorial Hall) contains thousands of tablets for deceased laypersons. The Joyoden (Founders hall) contains the ashes of Dōgen and his successors.[9] Here, images of the deceased are served food daily like they are living teachers. The Kichijokaku (visitor's center) is a large four-story modern building for lay persons, with kitchen, bath, sleeping rooms and a hall for zazen.[9]

In keeping with Zen's Mahayana tradition, there is an abundance of iconography in various buildings. At the Sanmon are four kings standing guard named Shitenno; the Buddha hall's main altar has three statues of Buddhas past, present and future; the Hatto displays Kannon the bodhisattva of compassion, and four white lions (called the a-un no shishi); the Yokusitsu has Baddabara; the Sanshokaku has a statue of Hotei; and the Tosu displays Ucchusma.[9] These artworks may be confusing to visitors unfamiliar with Buddhist art.[10]

The bronze temple bell dates to 1327 and is classified as an Important Cultural Property of Japan.[11] The Sanmon and Central Gate date from the 1794 rebuilding and are classified as Cultural Properties of Japan.[12][13]

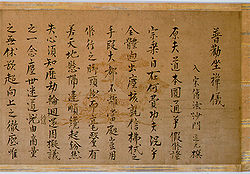

A number of important manuscripts belong to the temple, including the National Treasure Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen, by temple founder Dōgen (1233);[14] teachings he brought back from Song China (1227);[15] and a record of a subsidy for the earlier Sanmon in the hand of Emperor Go-En'yū (1372).[16]

Spread over a hillside, the complex is surrounded by cedar trees, some 100 feet (30 m) tall and as old as the temple.[17] It is surrounded by bright green moss-covered boulders, and Japanese maples that turn red and gold during autumn.[18]

Training

Today, Eihei-ji is the main training temple of Sōtō Zen. The standard training for a priest in Eihei-ji ranges from three months to a two-year period of practice. It is in communion with all Japanese Soto Zen temples, and with some temples in America, including the San Francisco Zen Center.

Head priests at Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji alternate terms leading Sotoshu (the Sōtō school of Zen). Fukuyama Taiho Zenji is the head priest, or abbott, who oversees trainees at Eihei-ji, and also began serving his second term as the head priest of Sotoshu in January 2012. His first term was from January 2008 to January 2010.[19]

About two hundred or two hundred fifty priests and nuns in training are in residence.[8][3] A single tatami, a 1 meter (3.3 ft) by 2 meters (6.6 ft) mat laid in rows on a raised platform called a tan in a common room, is provided for each trainee to eat, sleep, and meditate on.[17]

The monks start their day at 3:30 a.m., and one hour later during winter. They do zazen and read and chant sutras. Breakfast is a bowl of okayu (rice gruel) with pickles.[20] After breakfast they do chores: clean, weed, and, if needed, shovel snow. The floors and corridors have been polished smooth by daily cleaning for hundreds of years.[20] Then they read and chant again. Dinner at 5 p.m. is meager and ritualized: the position of the bowl and utensils is observed. Zazen or a lecture follows before bed at 9 p.m.[17] The trainees shave their heads and take a bath every five days.[18]

Eihei-ji has sought, since medieval times, a source of income by soliciting monks to purchase honorary titles.[6] Monks may progress through four hôkai (dharma ranks) with some time requirements of months or years between ranks. The final step in becoming a priest is zuise which means becoming ichiya-no-jûshoku (abbot for one night) at both head temples (Eihei-ji and Sôji-ji).

Tourism

Visitors to Eihei-ji are welcome, but must dress modestly and keep silent. They may attend one to three day meditation retreats for a fee.[17] Each visitor receives a list of rules, for example photography of the priests-in-training is prohibited.[2] More than one million visitors used to pass through the gates of Eihei-ji.[8] However, the number has declined and by 2003 only 800,000 tourists visited, a period during which the train service from Fukui to nearby Eiheiji guchi Station was temporarily halted.[18]

A memorial service, a major source of revenue for Eihei-ji,[6] has been held every fifty years since the sixteenth century on the anniversary of Dōgen Zenji's entering nirvana. For example in 1752 about 23,700 monks attended, which raised enough money to rebuild the main gate.[6] Groups from all over the world including a group from San Francisco formed to make a pilgrimage to Eihei-ji for the 750th anniversary in 2002.[21]

In 1905, Eihei-ji held its first conference called Genzō e on Dōgen Zenji's Shōbōgenzō. It succeeded in attracting so many interested parties that it became an annual event. Monks and laypersons, along with academic and popular writers can attend workshops each year.[6]

Branches

- Japan

- Chōkoku-ji (長谷寺), also known as the Eihei-ji Tokyo Betsuin (永平寺東京別院), in Tokyo.

- Chuō-ji (中央寺), also known as the Eihei-ji Sapporo Betsuin (永平寺札幌別院), in Sapporo.

- Taianden-gokoku-in (泰安殿護国院), also known as the Eihei-ji Nagoya Betsuin (永平寺名古屋別院), in Nagoya.

- Shōryū-ji (紹隆寺), also known as the Eihei-ji Kagoshima Shutchōjo (永平寺鹿児島出張所), in Kagoshima.

- U.S.A

- Zenshuji Soto Mission

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Heinrich Dumoulin, Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan (World Wisdom Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0941532907).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Eiheiji EiheijiKankoubussankyoukai. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Head Temple Eiheiji SotoZen-Net. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ↑ Hee-Jin Kim, Eihei Dogen: Mystical Realist (Wisdom Publications, 2000, ISBN 978-0861713769).

- ↑ William M. Bodiford, Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0824833039).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 William Bodiford, Remembering Dogen: Eiheiji and Dogen Hagiography The Journal of Japanese Studies 32(1) (2006): 1–21.

- ↑ Eiheiji Temple Japan Travel Online, Kintetsu International. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Japan Heritage Eiheiji: For a few bucks, you too can try for enlightenment The Asahi Shimbu, May 13, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Gabi Greve, Eihei-Ji Temple - Dogen Zenji Daruma Pilgrims in Japan, February 1, 2005. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ Douglas P. Sjoquist, Identifying Buddhist Images in Japanese Painting and Sculpture Education About Asia 4(3) (Winter 1999). Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 銅鐘 (Bronze bell) Fukui Prefecture. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 永平寺山門 (Eiheiji Sanmon) Fukui Prefecture. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 永平寺中雀門 (Eiheiji Central Gate) Fukui Prefecture. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 普勧坐禅儀 (Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen) Fukui Prefecture. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 紙本墨書 高祖嗣書 (Writing in black ink on paper - certificated by the master) Fukui Prefecture. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 紙本墨書 後円融院宸翰 (Writing in black ink on paper - in the hand of Emperor Go-En'yū) Fukui Prefecture. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Eihei-ji Fodor's, Random House. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Bill Willis, Austere monks in a lavish monastery The Japan Times, February 23, 2003. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ Fukuyama Taiho Zenji, Head Priest of Daihonzan Eiheiji, Appointed Head Priest of Sotoshu SotoZen-Net. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 James P. Zumwalt, Copying Sutras at Eiheiji Temple Z Notes, Official Blog of Tokyo Embassy, January 21, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ Soto Zen Education Center Activity Schedule Dharma Eye, May 2002. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bodiford, William. Remembering Dogen: Eiheiji and Dogen Hagiography The Journal of Japanese Studies 32(1) (2006): 1–21. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- Bodiford, William M. Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0824833039

- Dogen, Eihei. Shohaku Okumura (trans.), Taigen Daniel Leighton (ed.). Dogen's Pure Standards for the Zen Community: A Translation of Eihei Shingi. State University of New York Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0791427101

- Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan. World Wisdom Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0941532907

- Kim, Hee-Jin. Eihei Dogen: Mystical Realist. Wisdom Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-0861713769

External links

All links retrieved September 19, 2017.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.