El

Ēl (Hebrew: אל) is a northwest Semitic word meaning "god" or "God." In the English Bible, the derivative name Elohim is normally translated as "God," while Yahweh is translated as "The Lord." El can be translated either as "God" or "god," depending upon whether it refers to the one God or to a lesser divine being. As an element in proper names, "el" is found in ancient Aramaic, Arabic, and Ethiopic languages, as well as Hebrew (e.g. "Samu·el" and "Jo·el"). In the post-biblical period, "el" becomes a regular element in the names of angels such as "Gabri·el," "Micha·el," and "Azri·el," to denote their status as divine beings. The semantic root of the Islamic word for God "Allah" is related to the semitic word El.

In the Bible, El was the deity worshiped by the Hebrew patriarchs, for example as El Shaddai (God Almighty) or El Elyon (God Most High) before the revelation of his name Yahweh to Moses. But El was also worshiped by non-Israelites, such as Melchizedek (Genesis 14:9). Scholars have found much extra-biblical evidence of Canaanite worship of El as the supreme deity, creator of heaven and earth, the father of humankind, the husband of the goddess Asherah, and the parent of many other gods. Canaanite mythology about El may have directly influenced the development of the later Greco-Roman stories of the gods.

The theological position of Jews and Christians is that Ēl and Ĕlōhîm, when used to mean the supreme God, refer to the same being as Yahweh—the one supreme deity who is the Creator of the universe and the God of Israel. Whether or not this was the original belief of the earliest Biblical writers is a subject of much debate. Some form of monotheism probably existed among the Israelites from an early date, but scholars debate the extent to which they borrowed or inherited numerous polytheistic ideas from their Canaanite neighbors and forebears.

Ēl in the Bible

The Patriarchs and El

In Exodus 6:2–3, Yahweh states:

I revealed myself to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob as Ēl Shaddāi, but was not known to them by my name Yahweh.

Today we commonly hear the phrase "the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob." Abraham entered into a relationship with the God who was known as the "Shield of Abraham," Isaac covenanted with "the Fear of Isaac," and Jacob with "the Mighty One." The Bible identifies these personal gods as forms of the one high god El. Genesis indicates that not only the Hebrew patriarchs, but also their neighbors in Canaan and others throughout Mesopotamia, worshiped El as the highest God. For example, the king of the town of Salem (the future Jerusalem) greeted and blessed Abraham in the name of the "God Most High"—El Elyon:

- Melchizedek king of Salem brought out bread and wine. He was priest of God Most High [El Elyon], and he blessed Abram, saying, "Blessed be Abram by God Most High" (Gen. 14:19).

Soon after this, Abraham swore an oath to the king of Sodom in the name of El Elyon, identifying him as "The Creator of Heaven and earth" (Gen. 14:22). Later, when God established the covenant of circumcision with Abraham, he identified himself as El Shaddai—God Almighty (Gen. 17:1). It is also El Shaddai who blessed Jacob and told him to change his name to "Isra·el" (Gen. 35:10-11). And it is in El Shaddai's name that Jacob conferred his own blessing to his sons, the future patriarchs of the tribes of Israel:

- By the God (El) of you father, who helps you … the Almighty (Shaddai), who blesses you with blessings of the heavens above, blessings of the deep that lies below, blessings of the breast and womb (Gen. 49:25).

In Genesis 22, Abraham planted a sacred tree in Beersheba, calling upon the name of "El Olam"—God Everlasting. At Shechem, he established an altar in the name of "El Elohe Israel"—God, the God of Israel. (Gen. 33:20)

Finally, in Genesis 35, "Elohim" appeared to Jacob and ordered him and to move his clan to the town of Luz, there to build an altar to commemorate God's appearance. Jacob complied, erecting an altar to "El," and renaming the town "Beth-el"—the house, or place, of El.

Debate over origins

While the traditional view is that El later revealed himself to Moses as Yahweh, some scholars believe that Yahweh was originally thought to be one of many gods—or perhaps the god of one particular Israelite tribe, or the Kenite god of Moses' wife—and was not necessarily identified with Ēl at first (Smith 2002). They cite as evidence, for example, the fact that in some Biblical verses, Yahweh is clearly envisioned as a storm god, something not true of Ēl so far as is known.

- The voice of the Yahweh is over the waters; the God of glory thunders, the Lord thunders over the mighty waters…. The voice of the Yahweh strikes with flashes of lightning (Psalm 29:3-7).

Today a more widespread view is that such names as Ēl Shaddāi, Ēl ‘Ôlām, and Ēl ‘Elyôn were originally understood as one God with different titles according to their place of worship, just as today Catholics worship the same Mary as "Our Lady of Fatima" or "the Virgin of Guadalupe." Thus, it is possible that the religious identity of these figures was established in the popular Israelite mind from an early date. Otherwise, one is led to the view that all of traditions and terms of the various tribes were unified as one God by the religious authorities, who combined the J, E, D, and P sources of scripture, as the Israelites organized their nation during and after the Babylonian exile.

The Council of El

Psalm 82 presents a vision of God that may hearken back to the age in which El was seen as Israel's chief deity, rather than as the only God:

- Elohim (God) stands in the council of ēl

- he judges among the gods (elohim). (Psalm 82:1)

In context, this appears to signify that God stands in the divine council as the supreme deity, judging the other gods. He goes on to pronounce that although they are "sons of god" (bene elohim) these beings shall no longer be immortal, but shall die, as humans do.

- I said, 'You are gods (elohim); you are all sons of the Most High (Elyon);' But you will die like mere men; you will fall like every other ruler (82:6-7).

The passage bears striking similarities to a Canaanite text (see below) uncovered at Ugarit, describing El's struggle against the rebellious Baal and those deities who supported him. The Hebrew version could mark a point at which the earlier polytheistic tradition of Israel was giving way to a monotheistic tradition whereby God no longer co-existed with other lesser deities. Defenders of strict Biblical monotheism, however, insist that Psalm 82 does not refer to a literal council of "the gods," but to a council in which God judged either the fallen angels or human beings who had put themselves in the position of God.

The Bible contains several other references to the concept of the heavenly council. For example, Psalm 89:6-7 asks:

- Who is like Yahweh among the sons of El? In the council of the holy ones, El is greatly feared; he is more awesome than all who surround him.

Another version of the heavenly council using only Yahweh's name appears in I Kings 22, in which the prophet Michaiah reports the following vision:

- I saw the Yahweh sitting on his throne with all the host of heaven standing around him on his right and on his left. And Yahweh said, 'Who will entice (King) Ahab into attacking Ramoth Gilead and going to his death there?' One suggested this, and another that. Finally, a spirit came forward, stood before Yahweh and said, 'I will entice him.' 'By what means?' Yahweh asked. 'I will go out and be a lying spirit in the mouths of all his prophets,' he said. 'You will succeed in enticing him,' said Yahweh. 'Go and do it' (I Kings 22:19-22).

Here it is no longer lesser gods or "sons of El," but "spirits" who respond to God in the council. By the time of the Book of Job, the concept of the heavenly council had evolved from the more primitive version expressed in Psalms 82 and 86 to one in which "the angels came to present themselves before Yahweh, and Satan also came with them." (Job 1:6) Some scholars have thus concluded that what were once considered lesser deities or literal "sons of El" in Hebrew mythology had became mere angels of Yahweh by the time of the writing of Job.

Northern El versus Southern Yahweh?

Historically, as well as in the Biblical narrative, Yahwistic monotheism took root first in the southern kingdom of Judah, with the Temple of Jerusalem at its center. According the documentary hypothesis, various strands in the Pentateuch—the first five books of the Bible—reflect the theological views of several different authors. The verses that use "El" are thought to represent a tradition characteristic of the northern tribes, while the verses that speak of Yahweh come from a southern tradition.

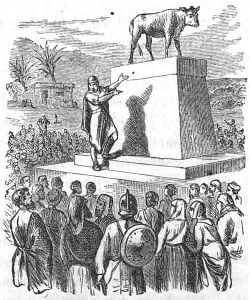

The north/south theological split is also referred to directly in the Bible itself. When Israel and Judah went their separate ways during the reign of Jeroboam I of Israel, Jeroboam stressed his kingdom's spiritual independence from Judah by establishing two northern religious shrines, one just north of Jerusalem at Bethel, the other further north in Dan. He is recorded as announcing:

- "It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem. Here is Elohim, O Israel, who brought you up out of Egypt" (1 Kings 12:28).

English translations usually render "elohim" in this case as "gods," but it is more likely "God." Since El was often associated with a sacred bull (see below), it is also likely that the golden bull-calf statues erected at these shrines represented an affirmation of El (or Yahweh/El) as the chief deity—if not the only god—of the Kingdom of Israel.

Various forms of El

The plural form ēlim (gods) occurs only four times in the Bible. Psalm 29 begins: "Ascribe to Yahweh, you sons of gods (benê ēlîm)." Psalm 89:6 asks: "Who in the skies compares to Yahweh, who can be likened to Yahweh among the sons of gods (benê ēlîm)." One of the other two occurrences is in the "Song of Moses," Exodus 15:11: "Who is like you among the gods (ēlim), Yahweh?" The final occurrence is in Daniel 11.35: "The king will do according to his pleasure; and he will exalt himself and magnify himself over every god (ēl), and against the God of gods (ēl ēlîm)."

The form ēlohim, translated "God," is not strictly speaking a plural, since even though it has the plural ending -im, it functions grammatically as a singular noun. Elohim was the normal word for the God of the Hebrews; it appears in the Hebrew Bible more frequently than any word for God except Yahweh.

The singular form ēl also appears frequently—217 times in the Masoretic (Hebrew) text: including 73 times in the Psalms and 55 times in the Book of Job. There are also places where the word ēl (god) is used to refer to a deity other than the God of Israel, especially when it is modified by the word "foreign," such as in Psalms 44:20 and 81:9, Deuteronomy 32:12, and Malachi 2:11.

Finally, archaeologists note that the linguistic form ēl appears in Israelite personal names from every period in which records survive, including the name Yiśrā’ēl 'Israel', meaning 'ēl strives'.

El outside the Bible

Middle Eastern Literature

El was found at the top of a list of gods in the ruins of the Royal Library of the Ebla civilization in Syria, dated to 2300 B.C.E. For the Canaanites, El or Ilu was the supreme god and the father of mankind, although a distant and somewhat aloof one. He may have been a desert god originally, for he reportedly built a sanctuary in the desert for himself, his wives, and their children. El fathered many gods, the most important being Hadad/Baal, Yaw, and Mot, which share similar attributes to the Greco-Roman gods Zeus, Poseidon and Hades respectively.

In ancient Canaanite inscriptions, El is often called Tôru ‘Ēl (Bull El or 'the bull god'), and several finds of bull [[statue[[s and icons are thought to represent this aspect of El worship. However, he is also often described or represented as an old bearded man—an image of God as the "ancient of days" that persists in the Bible in Daniel 7:9. Other titles of El include bātnyu binwāti (Creator of creatures), ’abū banī ’ili (father of the gods), and ‘abū ‘adami (father of man). He is called "creator eternal," as well as "your patriarch," "the gray-bearded ancient one," "full of wisdom," "King," "Father of years," and "the warrior."

In the Ugaritic "Ba‘al cycle," Ēl is introduced as dwelling on Mount Lel (possibly meaning "Night") at the headwaters of the "two rivers." He dwells in a tent, as did Yahweh in pre-monarchical Israel, which may explain why he had no temple in Ugarit. He is called latipanu ´ilu dupa´idu, "the Compassionate God of Mercy." Slow to anger, he is also entitled the Kindly One. He blesses humans and nearly always forgives them if they make atonement. He mourns for human pain and rejoices in human happiness. However, he remained at a distance, and often other deities, notably the goddesses Anat and Athirat/Ashera, were enlisted as mediators to gain his aid.

The Ugaritic text KTU 1.2:13-18 describes a scene similar to Psalm 82's version of the heavenly council. Here, El is the supreme god, and it is specified that the rebellious Baal, together with those gods who shelter him, must be brought to judgment:

- Straightaway turn ye your faces… towards the Assembly of the Convocation in the midst of the Mount of Lel. At the feet of El, do you indeed make obeisance… unto the Bull, my father, El…. Give up, O gods, him whom you are hiding, to whom they would be paying respect. Hand over Baal and his henchmen that I may humble him.

In lists of sacrificial offerings brought to the gods, El's name is mentioned frequently and prominently, even though apparently no temple was devoted specifically to him. Other titles by which El or El-type gods were worshiped at Ugarit included El Shaddai, El Elyon, and El Berith. Specifically named as children of El in the Ugaritic texts are Yamm (Sea), Mot (Death), Ashtar, and Ba‘al/Hadad. The latter, however, is also identified as descending from the god Dagon, with Ēl is in the position of a distant clan-father. In the episode of the "Palace of Ba‘al," Ba‘al/Hadad invited the "70 sons of Athirat" to a feast in his new palace. These sons of the goddess Athirat (Ashera) are thought to be fathered by Ēl.

In the wider Levantine region, the following references to El have been discovered by archeologists:

- A Phoenician inscribed amulet of the seventh century B.C.E. has been interpreted as reading:

The Eternal One (‘Olam) has made a covenant oath with us,

Asherah has made (a pact) with us.

And all the sons of El,

And the great council of all the Holy Ones.

With oaths of Heaven and Ancient Earth.

- An ancient mine inscription from the area of Mount Sinai reads ’ld‘lm—interpreted as to 'Ēl Eternal' or 'God Eternal'.

- In several inscriptions, the title "El (or Il), creator of Earth" appears. In Hittite texts, this expression becomes the single name Ilkunirsa, a title also given to the divine husband of Asherdu/Asherah and father of either 77 or 88 sons.

- In a Hurrian hymn to Ēl, the deity is called ’il brt and ’il dn, interpreted as 'Ēl of the covenant' and 'Ēl the judge' respectively.

Sanchuniathon's Account

The supposed writings, by the legendary Phoenician writer Sanchuniathon, partially preserved by the early church historian Eusebius of Caesaria, provide a fascinating account of the way in which the El of Canaanite mythology may have influenced later Greek myths. The writings are thought to be compilations of inscriptions from ancient Phoenician temples dating from possibly 2000 B.C.E. Here, Ēl is called both by the name Elus and its Greek equivalent of Cronus. However, he is not the creator god or first god. El is rather the son of Sky and Earth. Sky and Earth are themselves children of Elyon—the "Most High." El is the father of Persephone and Athene. He is the brother of the goddesses Aphrodite/Astarte, Rhea/Asherah, and Dione/Baalat, as well as of the gods Bethel, Dagon, and an unnamed god similar to the Greek Atlas.

In this story, Sky and Earth are estranged, but Sky forces himself on Earth and devours the children of this union. El attacks his father Sky with a sickle and spear and drives him off. In this way, El and his allies, the Eloim, gain Sky's kingdom. However, one of Sky's concubines was already pregnant, and her son now makes war on El. This god is called Demarus or Zeus, but he is markedly similar to the "Baal" who rebelled against El in the Ugaritic texts.

El had three wives, all of them his own sisters or half-sisters: Aphrodite/Astarte, Rhea/Asherah, and Dione. The latter is identified by Sanchuniathon with Baalat Gebal the tutelary goddess of Byblos, a city which Sanchuniathon says that El founded.

El and Poseidon

A bilingual inscription from Palmyra dated to the first century equates Ēl-Creator-of-the-Earth with the Greek god Poseidon. Earlier, a ninth century B.C.E. inscription at Karatepe identifies Ēl-Creator-of-the-Earth with a form of the name of the Babylonian water god Ea, lord of the watery subterranean abyss. This inscription lists Ēl in second place in the local pantheon, following Ba‘al Shamim and preceding the Eternal Sun.

Linguistic forms and meanings

Some Muslim scholars contend that the word "El" found in antiquity is actually none other than Allah when pronounced according to the tradition of Semitic languages. El should be pronounced "AL" since the first letter of El is 'alef, and the second letter could be pronounced double L. Ancient semitic civilizations did not write vowels and thus the A after L was missing, as well as the H.

Alternate forms of El are found throughout the semitic languages with the exception of the ancient Ge'ez language of Ethiopia. Forms include Ugaritic ’il (pl. ’lm); Phoenician ’l (pl. ’lm), Hebrew ’ēl (pl. ’ēlîm); Aramaic ’l; Arabic Al; Akkadian ilu (pl. ilāti).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bruneau, P. 1970. Recherches sur les cultes de Délos à l'époque hellénistique et à l'époque imperiale. Paris: E. de Broccard. (in French)

- Cross, Frank Moore. 1973. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674091760.

- Rosenthal, Franz. 1969. "The Amulet from Arslan Tash." in Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691035032.

- Smith, Mark S. 2002. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 9780802839725

- Teixidor, James. 1977. The Pagan God. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691072205

External Links

All links retrieved March 9, 2019.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

_MET_DP835806.jpg/250px-Melchizedek_Blesses_Abram_(Dalziels%27_Bible_Gallery)_MET_DP835806.jpg)