Elgin Marbles

The Elgin Marbles (IPA: /'ɛl gən/), also known as the Parthenon Marbles or Parthenon Sculptures, are a large collection of marble sculptures removed from Athens to Britain in 1806 by Lord Elgin, ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799 to 1803. The sculptures were purchased by the British Parliament from Lord Elgin and presented to the British Museum, London in 1816 where they have remained on display to the public.

Ever since the extradition of these Elgin marbles from the Parthenon, international debate, controversy, and outrage has surrounded the friezes, about how the antiquities had been "defaced by British hands." It is ambiguous about whether Lord Elgin was legally entitled to these art pieces as he obtained them from the Turks, who were then in charge of Athens' permission to control the Parthenon. The terms and responsibilities continue to be disputed to this day.

Unfortunately, due to the dispute over ownership and placement, the beauty and majesty of these wonderful works of art has been under-appreciated. Although Elgin may be criticized for his methods, it should also be remembered that they were typical of his time. His intention was to bring the pieces to safety, even spending considerable resources to rescue the shipload that sank, and make them available for public display. The mission of a museum, and the British Museum continues to advance this purpose, is to display artworks to the public and to keep them safe. Appreciation of these monumental works of art is therefore a priority for future generations.

Acquisition

During the first ten years of the nineteenth century, Lord Thomas Elgin (British Ambassador to Constantinople 1799-1803) removed entire boatloads of ancient sculpture from Athens. The pride of this collection was a huge quantity of fifth century B.C.E. sculpture from the Parthenon, the temple to the goddess Athena, which stood atop the Acropolis.

Taking advantage of Ottoman occupation over Greece, Lord Elgin obtained a firman for their removal from the Parthenon from the Ottoman Sultan. They were eventually purchased by Parliament for the nation in 1816 for £35,000 and deposited in the British Museum, where they were displayed in the Elgin Room until the purpose-built Duveen Gallery was completed. These have come to be known as the Elgin marbles.

Criticism by Elgin's contemporaries

When the marbles were shipped to Britain, there was great criticism of Lord Elgin (who had spent a fortune on the project), accusing him of vandalism and looting, but also much admiration of the sculptures. Lord Byron strongly objected to their removal from Greece:

- Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

- Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

- By British hands, which it had best behoved

- To guard those relics ne’er to be restored.

- Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

- And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

- And snatch'd thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!

- —"Childe Harold's Pilgrimage"

Byron was not the only Englishman to protest the removal at the time, Sir John Newport announced:

The Honourable Lord has taken advantage of the most unjustifiable means and has committed the most flagrant pillages. It was, it seems, fatal that a representative of our country loot those objects that the Turks and other barbarians had considered sacred.

A contemporary MP Thomas Hughes, an eye witness, later wrote:

The abduction of small parts of the Parthenon, of a value relatively small but which previously contributed to the solidity of the building, left that glorious edifice exposed to premature ruin and degradation. The abduction dislodged from their original positions, wherefrom they precisely drew their interest and beauty, many pieces which are altogether unnecessary to the country that now owns them.

John Keats was one of those who saw them privately exhibited in London. His sonnet On Seeing the Elgin Marbles for the First Time, which begins "My spirit is too weak," reveals the deep impression these sculptures had on him.

Some scholars, notably Richard Payne Knight, insisted that the marbles dated from the period of the Roman Empire, but most accepted that they were authentic works from the studio of Phidias, the most famous ancient Greek sculptor.

Description

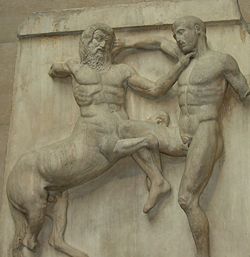

The Elgin Marbles include some of the statuary from the pediments, the metope panels depicting battles between the Lapiths and the Centaurs, as well as the Parthenon Frieze which decorated the horizontal course set above the interior architrave of the temple. As such, they represent more than half of what now remains of the surviving sculptural decoration of the Parthenon: the Elgin marbles and frieze extend to about one kilometer when laid out flat, 15 out of 92 metopes; 17 partial figures from the pediments, as well as other pieces of architecture.

Elgin's acquisitions also included objects from other buildings on the Athenian Acropolis: the Erechtheion, reduced to ruin during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1833); the Propylaia, and the Temple of Athena Nike. Lord Elgin took half of the marbles from the Parthenon and wax casts were produced from the remaining ones. At present, about two-thirds of the frieze is in London at the British Museum and a third remains in Athens, although much of the Athenian material is not on display. There are also fragments in nine other international museums.

Interpretation of the frieze

Considerable debate surrounds the meaning of the frieze, but most agree that it depicts the Panathenaic procession that paraded from Eleusis to Athens every four years. The procession on the frieze culminates at the east end of the Parthenon in a depiction of the Greek gods who are seated mainly on stools, on either side of temple servants in their midst. This section of the frieze is under-appreciated as it has been split between London and Athens. A doorway in the British Museum marks the absence of the relevant section of frieze. An almost complete copy of this section of the frieze is displayed and open to the public at Hammerwood Park near East Grinstead in Sussex.

Damage to the Marbles

To facilitate transport, the column capital of the Parthenon and many metopes and slabs were sawn and sliced into smaller sections. One shipload of marbles on board the British brig Mentor was caught in a storm off Cape Matapan and sank near Kythera, but was salvaged at the Earl's personal expense; it took two years to bring them to the surface.[1]

The artifacts held in London, unlike those remaining on the Parthenon, were saved from the hazards of pollution, neglect, and war. However, they were irrevocably damaged by the unauthorized "cleaning" methods employed by British Museum staff in the 1930s, who were dismissed when this was discovered. Acting under the erroneous belief that the marbles were originally bright white, the marbles were cleaned with copper tools and caustics, causing serious damage and altering the marbles' coloring. (The Pentelicon marble on which the carvings were made naturally acquires a tan color similar to honey when exposed to air.) In addition, the process scraped away all traces of surface coloring that the marbles originally held, but more regrettably, the detailed tone of many carvings were lost forever. The British Museum held an internal inquiry and those responsible were dismissed from the museum. However, the extent of any possible damage soon became exaggerated in heated controversy.[2] [3]

The Greek claim to the Marbles

The Greek government has claimed that the marbles should be returned to Athens on moral grounds, although it is no longer feasible or advisable to reposition them at the Parthenon. As part of the campaign, it is building the New Acropolis Museum, designed by the Swiss-American architect Bernard Tschumi, designed to hold the Parthenon sculptures arranged in the same way as they would have been on the Parthenon. It is intended to leave the spaces for the Elgin Marbles empty, rather than using casts in these positions, as a reminder to visitors of the fact that parts are held in other museums. The new museum plan also attracted controversy; the construction site contains late Roman and early Christian archaeology, including an unusual seventh century Byzantine bath house and other finds from Late Antiquity.

The British Museum position

A range of arguments has been expressed by British Museum spokespersons over the years in defense of retention of the Elgin Marbles within the museum. The main points include the maintenance of a single worldwide-oriented cultural collection, all viewable in one location, thereby serving as a world heritage center; the saving of the marbles from what would have been, or would be, pollution and other damage if relocated back to Athens; and a legal position that the museum is banned by charter from returning any part of its collection.[4] The latter was tested in the British High Court in May 2005 in relation to Nazi-looted Old Master artworks held at the museum; it was ruled that these could not be returned.[5] The judge, Sir Andrew Morritt, ruled that the British Museum Act – which protects the collections for posterity – cannot be overridden by a "moral obligation" to return works known to have been plundered. It has been argued, however, that connections between the legal ruling and the Elgin Marbles were more tenuous than implied by the Attorney General.[6]

Other displaced Parthenon art

Lord Elgin was neither the first, nor the last, to disperse elements of the marbles from their original location. The remainder of the surviving sculptures that are not in museums or storerooms in Athens are held in museums in various locations across Europe. The British Museum also holds additional fragments from the Parthenon sculptures acquired from various collections that have no connection with Lord Elgin.

Material from the Parthenon was dispersed both before and after Elgin's activities. The British Museum holds approximately half of the surviving sculptures. The remainder is divided among the following locations:

- Athens:

- Extensive remains of the metopes (especially east, north and west), frieze (especially west) and pediments

- Less than 50 percent is on public display and some is still on the building.

- Louvre, Paris:

- One frieze slab

- One metope

- Fragments of the frieze and metopes

- A head from the pediments

- National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen:

- Two heads from a metope in the British Museum

- University of Würzburg, Würzburg:

- Head from a metope in the British Museum

- Museo Salinas, Palermo:

- Fragment of frieze

- Vatican Museums:

- Fragments of metopes, frieze and pediments

- Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna:

- Three fragments of frieze

- Glyptothek, Munich:

- Fragments of metopes and frieze; not on display

The collection held in the British Museum includes the following material from the Acropolis:

- Parthenon: 247 ft of the original 524 ft of frieze

- 15 of the 92 metopes

- 17 pedimental figures; various pieces of architecture

- Erechtheion: a Caryatid, a column and other architectural members

- Propylaia: Architectural members

- Temple of Athena Nike: 4 slabs of the frieze and architectural members

Notes

- ↑ Epaminondas Vranopoulos, The Parthenon and the Elgin Marbles Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ↑ The British Museum, The cleaning of the Parthenon Sculptures in 1938 Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ↑ Ian Jenkins, Cleaning and Controversy: The Parthenon Sculptures 1811–1939 (British Museum Occasional Paper No. 146. British Museum Press, 2001, ISBN 0861591461). Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ↑ The Parthenon sculptures: stewardship The Britisn Museum. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ Ruling tightens grip on Parthenon marbles guardian.co.uk (May 27, 2005). Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ What does the Feldmann case verdict mean for the Elgin Marbles Elginism (June 3, 2005). Retrieved February 15, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beard, Mary. The Parthenon. Profile Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1861973016

- Hitchens, Christopher, Robert Browning, and Graham Binns. The Elgin Marbles: Should they be returned to Greece? Verso, 1998. ISBN 1859842208

- Jenkins, Ian. Cleaning and Controversy: The Parthenon Sculptures 1811–1939. British Museum Press, 2001. ISBN 0861591461

- Jenkins, Ian. The Parthenon Frieze. British Museum Press, 2002. ISBN 0714122378

- King, Dorothy. The Elgin Marbles. Hutchinson, 2006. ISBN 978-0091800130

- St. Clair, William. Lord Elgin and the Marbles, third rev. ed. Oxford University Press 1998 (original 1967). ISBN 978-0192880536

External links

All links retrieved September 14, 2017.

- A guide to the case for the restitution of the Parthenon Marbles

- BBC News—Swede gives back Acropolis marble

- British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles' site

- Demand for the return of Elgin Marbles

- Lord Elgin: Saviour or Vandal? Mary Beard BBC

- Elgin Marbles: fact or fiction? Dr. Dorothy King. guardian.uk.

- The British Museum Parthenon pages

- The International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures

- The Elgin Marbles - Parthenon Frieze

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.