Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney (December 8, 1765 - January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, pioneer, mechanical engineer, and manufacturer. He is best remembered as the inventor of the cotton gin. Whitney also affected the industrial development of the United States when, in manufacturing muskets for the government, he applied the idea of interchangeable parts toward a manufacturing system that gave birth to the American mass-production concept.

Whitney saw that a machine to clean the seed from cotton could make the South prosperous and make its inventor rich. He set to work at once and soon constructed a crude model that separated cotton fiber from seed. After perfecting his machine he filed an application for a patent on June 20, 1793; in February 1794, he deposited a model at the U.S. Patent Office, and on March 14, he received his patent. Whitney's gin brought the South prosperity, but the unwillingness of planters to pay for its use, together with the ease with which the gin could be pirated, put Whitney's company out of business by 1797.

When Congress refused to renew his patent, which expired in 1807, Whitney concluded that "an invention can be so valuable as to be worthless to the inventor." He never patented his later inventions, one of which was a milling machine. His genius—as expressed in tools, machines, and technological ideas—made the southern United States dominant in cotton production and the northern states a bastion of industry. Although he made his fortune in musket production, Whitney's name will be forever linked to his cotton gin.

Early life

Whitney was born in Westborough, Massachusetts, on December 8, 1765, the eldest child of Eli Whitney, a prosperous farmer, and Elizabeth Fay of Westborough. Very early in life he demonstrated his mechanical genius and entrepreneurial acumen, operating a profitable nail-manufacturing operation in his father's workshop during the American Revolution. Because his step-mother opposed his wish to attend college, Whitney worked as a farm laborer and schoolteacher to save money. He prepared for Yale under the tutelage of Rev. Elizur Goodrich of Durham, Connecticut, and entered the Class of 1792.

Whitney expected to study law but, finding himself short of funds on graduation, accepted an offer to go to South Carolina as a private tutor. Instead of reaching his destination, he was convinced to visit Georgia, which was then a magnet for New Englanders seeking their fortunes. One of his shipmates was the widow and family of Revolutionary hero, General Nathanael Greene, of Rhode Island. Mrs. Catherine Littlefield Greene invited Whitney to visit her Georgia plantation, Mulberry Grove. Her plantation manager and husband-to-be was Phineas Miller, another Connecticut migrant and Yale graduate (Class of 1785), who would become Whitney's business partner.

Whitney's two most famous innovations would divide the country in the mid-nineteenth century; the cotton gin (1793), which revolutionized the way Southern cotton was cropped and reinvigorated slavery; and his method of manufacturing interchangeable parts, which would revolutionize Northern industry and, in time, be a major factor in the North's victory in the Civil War.

Career inventions

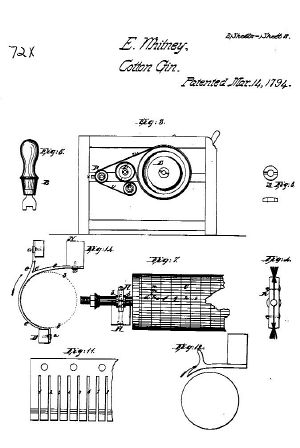

Cotton gin

The cotton gin is a mechanical device which removes the seeds from cotton, a process which had, until the time of its invention, been extremely labor-intensive. The cotton gin was a wooden drum stuck with hooks, which pulled the cotton fibers through a mesh. The cotton seeds would not fit through the mesh and fell outside.

While others had realized that some kind of device would make the work more efficient, none had been successfully built and patented. Whether Eli Whitney was the sole inventor of the cotton gin machine has been debated. Apparently Catherine Greene encouraged his efforts, and it has been suggested that her ideas were crucial to the successful development of the cotton gin. Historians have also argued that slaves had already been using a comb-like device to clean cotton, and Whitney took the idea for his own machine. Since neither slaves could apply for patents, nor could their owners apply for them on their behalf, no acknowledgement of a slave's contribution to the invention could be documented and therefore is impossible to prove.

After perfecting his cotton gin machine Whitney filed an application for a patent on June 20, 1793; in February 1794, he deposited a model at the U.S. Patent Office; and he received his patent (later numbered as X72) on March 14, 1794. He and his partner Phineas Miller did not intend to sell the gins. Rather, like the proprietors of grist and sawmills, they expected to charge farmers for cleaning their cotton, at the rate of two-fifths of the profits, paid in cotton. Resentment at this scheme, the mechanical simplicity of the device, and the primitive state of patent law, made infringement inevitable. Whitney's cotton gin company went out of business in 1797.

While the cotton gin did not earn Whitney the fortune he had hoped for, it did transform Southern agriculture and the national economy. Southern cotton found ready markets in Europe and in the burgeoning textile mills of New England. Cotton agriculture revived the profitability of slavery and the political power of supporters of the South's "peculiar institution." By the 1820s, the dominant issues in American politics were driven by "King Cotton:" Maintaining the political balance between slave and free states, and tariff protection for American industry.

Interchangeable parts

Though best known for his invention of the cotton gin, Eli Whitney's greatest long-term innovation was actually pioneering the era of mass production and modern manufacturing methods, based on the novel concept of interchangeable parts, subjects which greatly interested him. French gunsmith Honore Le Blanc Credit is most often given credit for the idea of interchangeable parts. In the mid-eighteenth century, Le Blanc proposed making gun parts from standardized patterns using jigs, dies, and molds. Since all the parts would be the same, then a broken part could be easily replaced by another, identical part. However, Le Blanc did not get very far with his ideas since other gunsmiths feared that their one-of-a-kind weapons would soon become outdated. Nonetheless, Thomas Jefferson, then living in France, was captivated with the idea of interchangeability and brought it to America, where it gained a more ready audience.

By the late 1790s, Whitney was on the verge of financial ruin, as cotton gin litigation had all but buried him in debt. His New Haven, Connecticut, cotton gin factory had burned to the ground, and litigation was draining his remaining resources. Meanwhile, the French Revolution had ignited new conflicts between England, France, and the United States. The new American government, realizing the need to prepare for war, began to rearm in earnest.

In January 1798, the federal government—fearing war with France—awarded Whitney a contract of $134,000 to produce and deliver 10,000 muskets. With this contract, Whitney refined and successfully applied his revolutionary "Uniformity System" of manufacturing interchangeable components. Though it took ten years to deliver the last of the muskets, the government's investment and support enabled Whitney to prove the feasibility of his system and establish it as the chief originator of the modern assembly line.

Whitney demonstrated that machine tools—run by workers who did not require the highly specialized skills of gunsmiths—could make standardized parts to precise specifications, and that any part made could be used as a component of any musket. The firearms factory he built in New Haven was thus one of the very first to use mass production methods.

Later life, death

Despite his humble origins, Whitney was keenly aware of the value of social and political connections. In building his arms business, he took full advantage of the access that his status as a Yale alumnus gave him to other well-placed graduates, like Secretary of War Oliver Wolcott (Class of 1778) and New Haven developer and political leader James Hillhouse. His 1817 marriage to Henrietta Edwards, granddaughter of the famed evangelist, Jonathan Edwards, daughter of Pierpont Edwards, head of the Democratic Party in Connecticut, and first cousin of Yale's president, Timothy Dwight, the state's leading Federalist, further tied him to Connecticut's ruling elite. In a business dependent on government contracts, such connections were essential to success.

Whitney died of prostate cancer on January 8, 1825, leaving a widow and four children. Eli Whitney and his descendants are buried in New Haven's historic Grove Street Cemetery. Yale College's Eli Whitney Students Program, which is one of the four doors into Yale College, is named after Whitney in recognition of his venerable age at the time of his entrance to Yale College in 1792; he was twenty-seven years old.

The armory

Whitney's armory was left in the charge of his talented nephews, Eli Whitney and Philos Blake, notable inventors and manufacturers in their own right, they invented the mortise lock and the stone-crushing machine.

Eli Whitney, Jr. (1820-1894) assumed control of the armory in 1841. Working under contract to inventor Samuel Colt, the younger Whitney manufactured the famous "Whitneyville Walker Colts" for the Texas Rangers. (The success of this contract rescued Colt from financial ruin and enabled him to establish his own famous arms company). Whitney's marriage to Sarah Dalliba, daughter of the U.S. Army's chief of ordinance, helped to assure the continuing success of his business.

The younger Whitney organized the New Haven Water Company, which began operations in 1862. While this enterprise addressed the city's need for water, it also enabled the younger Whitney to increase the amount of power available for his manufacturing operations at the expense of the water company's stockholders. Originally located in three sites along the Mill River, the new dam made it possible to consolidate his operations in a single plant.

Whitney's grandson, Eli Whitney IV (1847-1924), sold the Whitney Armory to Winchester Repeating Arms, another notable New Haven gun company, in 1888. He served as president of the water company until his death and was a major New Haven business and civic leader. He played an important role in the development of New Haven's Ronan-Edgehill Neighborhood.

Following the closure of the armory, the factory site continued to be used for a variety of industrial purposes, including the water company. Many of the original armory buildings remained intact until the 1960s. In the 1970s, as part of the Bicentennial celebration, interested citizens organized the Eli Whitney Museum, which opened to the public in 1984. The site today includes the boarding house and barn that served Eli Whitney's original workers and a stone, storage building from the original armory. Museum exhibits and programs are housed in a factory building constructed c. 1910. A water-company, office building constructed in the 1880s now houses educational programs operated by the South Central Connecticut Regional Water Authority, which succeeded the New Haven Water Company.

Legacy

Whitney's two most famous innovations would dramatically divide the country in the mid-nineteenth century. The cotton gin (1793) reinvigorated slavery by making it more profitable, and his system of interchangeable parts would ultimately become a major factor in the North's victory in the Civil War.

The cotton gin could generate up to 55 pounds of cleaned cotton daily. This contributed to the economic development of the Southern states of the United States, a prime, cotton-growing area. Many historians believe that this invention allowed for the African slavery system in the Southern United States to become more sustainable at a critical point in its development.

His translation of the concept of interchangeable parts into a manufacturing system gave birth to the American mass production concept that would make a wide range of essential goods and products available to many more people. Whitney's employment in his manufacturing process of power machinery and the division of labor played a significant role in the subsequent industrial revolution that was to transform American life.

Whitney was inducted into the National Inventor's Hall of Fame in 1974.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Green, Constance M. Eli Whitney and the Birth of American Technology. Longman, 1997. ISBN 978-0673393388

- Hall, Karyl Lee Kibler. Windows on the Works: Industry on the Eli Whitney Site, 1798-1979. Eli Whitney Museum, 1985. ISBN 978-0931001000

- Hounshell, David. From the American System to Mass Production, 1800-1932. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0801831584

- Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0801882722

- Stegeman, John F., and Janet A. Stegeman. Caty: A Biography of Catharine Littlefield Greene. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0820307923

- Woodbury, Robert S. The Legend of Eli Whitney and Interchangeable Parts. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1964. ASIN B0007FD1JU

External links

All links retrieved September 14, 2017.

- The Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop

- The Cotton Gin and Eli Whitney. By Mary Bellis, ThoughtCo.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.