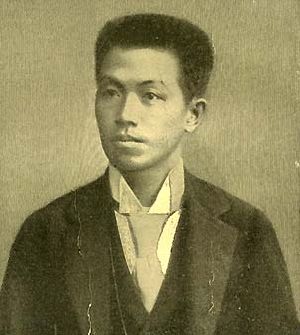

Emilio Aguinaldo

| Emilio Aguinaldo | |

| |

1st President of the Philippines

President of the Tejeros Convention President of the Biyak-na-Bato Republic Dictator of the Dictatorial Government President of the Revolutionary Government President of the 1st Philippine Republic | |

| In office March 22, 1897 – April 1, 1901 | |

| Vice President(s) | Mariano Trias |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Newly Established |

| Succeeded by | Manuel L. Quezon (position abolished 1901-1935) |

| Born | March 22 1869 Cavite El Viejo (Kawit), Cavite |

| Died | February 6 1964 (aged 94) Quezon City, Metro Manila |

| Political party | Magdalo faction of the Katipunan, National Socialist Party |

| Spouse | (1) Hilaria del Rosario-died (2) Maria Agoncillo |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Signature | |

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (March 22, 1869 – February 6, 1964) was a Filipino general, politician, and independence leader. He played an instrumental role in Philippine independence during the Philippine Revolution against Spain and the Philippine-American War to resist American occupation. In 1895, Aguinaldo joined the Katipunan rebellion, a secret organization then led by Andrés Bonifacio, dedicated to the expulsion of the Spanish and independence of the Philippines through armed force. He quickly rose to the rank of General, and established a power base among rebel forces. Defeated by the Spanish forces, he accepted exile in December 1897. After the start of the Spanish American War, he returned to the Philippines, where he established a provisional dictatorial government and, on June 12, 1898, proclaimed Philippine independence. Soon after the defeat of the Spanish, open fighting broke out between American troops and pro-independence Filipinos. Superior American firepower drove Filipino troops away from the city, and the Malolos government had to move from one place to another. Aguinaldo eventually pledged his allegiance to the U.S. government in March of 1901, and retired from public life.

In the Philippines, Aguinaldo is considered to be the country's first and the youngest Philippine President, though his government failed to obtain any foreign recognition.

Early life and career

The seventh of eight children of Crispulo Aguinaldo and Trinidad Famy, Emilio Aguinaldo was born into a Filipino family on March 22, 1869, in Cavite El Viejo (now Kawit), Cavite province. His father was gobernadorcillo (town head), and, as members of the Chinese-mestizo minority, his family enjoyed relative wealth and power.

At the age of two, he contracted smallpox and was given up for dead until he opened his eyes. At three, he was bitten by hundreds of ants when a relative abandoned him in a bamboo clump while hiding from some Spanish troops on mission of retaliation for the Cavite Mutiny of 1872. He almost drowned when he jumped into the Marulas River on a playmate’s dare, and found he did not know how to swim.

As a young boy, Aguinaldo received basic education from his great-aunt and later attended the town's elementary school. In 1880, he took up his secondary course education at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran, which he quit on his third year to return home instead to help his widowed mother manage their farm.

At the age of 17, Emilio was elected cabeza de barangay of Binakayan, the most progressive barrio of Cavite El Viejo. He held this position, representing the local residents, for eight years. He also engaged in inter-island shipping, traveling as far south as the Sulu Archipelago. Once on a trading voyage to the nearby southern islands, while riding in a big paraw (sailboat with outriggers), he grappled with, subdued, and landed a large man-eating shark, thinking it was just a large fish.

In 1893, the Maura Law was passed to reorganize town governments with the aim of making them more effective and autonomous, changing the designation of town head from gobernadorcillo to capitan municipal, effective 1895. On January 1, 1895, Aguinaldo was elected town head, becoming the first person to hold the title of capitan municipal of Cavite El Viejo.

Family

His first marriage was in 1896, with Hilaria Del Rosario(1877-1921), and they had five children (Miguel, Carmen, Emilio Jr., Maria, and Cristina). On March 6, 1921, his first wife died, and in 1930, he married Dona Maria Agoncillo, niece of Don Felipe Agoncillo, the pioneer Filipino diplomat.

Several of Aguinaldo's descendants became prominent political figures in their own right. A grandnephew, Cesar Virata, served as Prime Minister of the Philippines from 1981 to 1986. Aguinaldo's granddaughter, Ameurfina Melencio Herrera, served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1979 until 1992. His great-grandson, Joseph Emilio Abaya, was elected House of Representatives to the 13th and 14th Congress, representing the 1st District of Cavite. The present mayor of Kawit, Cavite, Reynaldo Aguinaldo, is a grandson of the former president, while the vice-mayor, Emilio "Orange" Aguinaldo IV, is a great-grandson.

Philippine revolution

In 1895, Aguinaldo joined the Katipunan rebellion, a secret organization then led by Andrés Bonifacio, dedicated to the expulsion of the Spanish and independence of the Philippines through armed force. He joined as a lieutenant under Gen. Baldomero Aguinaldo and rose to the rank of general in a few months. The same week that he received his new rank, 30,000 members of the Katipunan launched an attack against the Spanish colonists. Only Emilio Aguinaldo’s troops launched a successful attack. In 1896, the Philippines erupted in revolt against the Spaniards. Aguinaldo won major victories for the Katipunan in Cavite Province, temporarily driving the Spanish out of the area. However, renewed Spanish military pressure compelled the rebels to restructure their forces in a more cohesive manner. The insulated fragmentation that had protected the Katipunan's secrecy had outlived its usefulness. By now, the Katipunan had divided into two factions; one, the Magdalo, led by Aguinaldo and based in Kawit, thought that it was time to organize a revolutionary government to replace the Katipunan. The other, named Magdiwang and led by Bonifacio, opposed this move.

On March 22, 1897, Bonifacio presided over the Tejeros Convention in Tejeros, Cavite (deep in Baldomero Aguinaldo territory), to elect a revolutionary government in place of the Katipunan. Away from his power base, Bonifacio unexpectedly lost the leadership to Aguinaldo, and was elected instead to the office of Secretary of the Interior. Even this was questioned by an Aguinaldo supporter, who claimed that Bonifacio did not have the necessary schooling for the job. Insulted, Bonifacio declared the Convention null and void, and sought to return to his power base in Rizal. Bonifacio was charged, tried, found guilty of treason (in absentia), and sentenced to death by a Cavite military tribunal. He and his party were intercepted by Aguinaldo's men in a violent encounter that left Bonifacio mortally wounded. Aguinaldo confirmed the death sentence, and the dying Bonifacio was hauled to the mountains of Maragondon in Cavite, and executed on May 10, 1897, even as Aguinaldo and his forces were retreating in the face of Spanish assault.

Biak-na-Bato

In June, Spanish pressure intensified, eventually forcing Aguinaldo's revolutionary government to retreat to the village of Biak-na-Bato in the mountains. General Emilio Aguinaldo negotiated the Pact of Biak-na-Bato, which specified that the Spanish would give self-rule to the Philippines within three years if Aguinaldo went into exile. Under the pact, Aguinaldo agreed to end hostilities as well in exchange for amnesty and 800,000 pesos (Filipino money) as an indemnity. He and the other revolutionary leaders would go into voluntary exile. Another 900,000 pesos was to be given to the revolutionaries who remained in the Philippines, who agreed to surrender their arms; general amnesty would be granted and the Spaniards would institute reforms in the colony. On December 14, 1897, Aguinaldo was shipped to Hong Kong, along with some of the members of his revolutionary government. Emilio Aguinaldo was President and Mariano Trias (Vice President); other officials included Antonio Montenegro as Minister of Foreign Affairs, Isabelo Artacho as Minister of the Interior, Baldomero Aguinaldo as Minister of the Treasury, and Emiliano Riego de Dios as Minister of War.

Spanish-American War

Thousands of other Katipuneros continued to fight the Revolution against Spain for a sovereign nation. In May 1898, war broke out between Spain and the United States and a Spanish warship was sunk in Manila Bay by the fleet of U.S. Admiral George Dewey. Aguinaldo, who had already agreed to a supposed alliance with the United States through the American consul in Singapore, returned to the Philippines in May 1898, and immediately resumed revolutionary activities against the Spaniards, now receiving verbal encouragement from emissaries of the United States. In Cavite, on the advice of lawyer Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista, he established a provisional dictatorial government to "repress with a strong hand the anarchy which is the inevitable sequel of all revolutions." On June 12, 1898, he proclaimed Philippine independence in Kawit, and began to organize local political units all over the Philippines.

From Cavite, Aguinaldo led his troops to victory after victory over the Spanish forces until they reached the city of Manila. After the surrender of the Spaniards, however, the Americans forbade the Filipinos to enter the Walled City of Intramuros. Aguinaldo convened a Revolutionary Congress at Malolos to ratify the independence of the Philippines and to draft a constitution for a republican form of government.

Presidency of the First Republic of the Philippines

Aguinaldo Cabinet

President Aguinaldo had two cabinets in the year 1899. Thereafter, the war situation resulted in his ruling by decree.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Philippine-American War

On the night of February 4, 1899, a Filipino was shot by an American sentry as he crossed Silencio Street, Sta. Mesa, Manila. This incident is considered the beginning of the Philippine-American War, and open fighting soon broke out between American troops and pro-independence Filipinos. Superior American firepower drove Filipino troops away from the city, and the Malolos government had to move from one place to another. Offers by U.S. President William McKinley to set up an autonomous Philippine government under an American flag were rejected.

Aguinaldo led resistance to the Americans, then retreated to northern Luzon with the Americans on his trail. On June 2, 1899, Gen. Antonio Luna, an arrogant but brilliant general and Aguinaldo’s looming rival in the military hierarchy, received a telegram from Aguinaldo, ordering him to proceed to Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, for a meeting at the Cabanatuan Church Convent. Three days later, on June 5, Luna arrived and learned that Aguinaldo was not at the appointed place. As Gen. Luna was about to depart, he was shot, then stabbed to death by Aguinaldo's men. Luna was later buried in the churchyard; Aguinaldo made no attempt to punish or discipline Luna's murderers.

Less than two years later, after the famous Battle of Tirad Pass and the death of his last most trusted general, Gregorio del Pilar, Aguinaldo was captured in Palanan, Isabela, on March 23, 1901, by U.S. General Frederick Funston, with the help of Macabebe trackers. The American task force gained access to Aguinaldo's camp by pretending to be captured prisoners.

Funston later noted Aguinaldo's "dignified bearing," "excellent qualities," and "humane instincts." Aguinaldo volunteered to swear fealty to the United States, if his life was spared. Aguinaldo pledged allegiance to America on April 1, 1901, formally ending the First Republic and recognizing the sovereignty of the United States over the Philippines. He issued a manifesto urging the revolutionaries to lay down their arms. Others, like Miguel Malvar and Macario Sakay, continued to resist the American occupation.

U.S. occupation

Aguinaldo retired from public life for many years. During the United States occupation, Aguinaldo organized the Asociación de los Veteranos de la Revolución (Association of Veterans of the Revolution), which worked to secure pensions for its members and made arrangements for them to buy land on installment from the government.

When the American government finally allowed the Philippine flag to be displayed in 1919, Aguinaldo transformed his home in Kawit into a monument to the flag, the revolution, and the declaration of Independence. His home still stands, and is known as the Aguinaldo Shrine.

In 1935, when the Commonwealth of the Philippines was established in preparation for Philippine independence, he ran for president but lost by a landslide to fiery Spanish mestizo, Manuel L. Quezon. The two men formally reconciled in 1941, when President Quezon moved Flag Day to June 12, to commemorate the proclamation of Philippine independence.

Aguinaldo again retired to private life, until the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in World War II. He cooperated with the Japanese, making speeches, issuing articles, and infamous radio addresses in support of the Japanese—including a radio appeal to Gen. Douglas MacArthur on Corregidor to surrender in order to spare the flower of Filipino youth. After the Americans retook the Philippines, Aguinaldo was arrested along with several others accused of collaboration with the Japanese. He was held in Bilibid prison for months until released by presidential amnesty. In his trial, it was eventually deemed that his collaboration with the Japanese was probably made under great duress, and he was released.

Aguinaldo lived to see independence granted to the Philippines July 4, 1946, when the United States Government marked the full restoration and recognition of Philippine sovereignty. He was 93 when President Diosdado Macapagal officially changed the date of independence from July 4 to June 12, 1898, the date Aguinaldo believed to be the true Independence Day. During the independence parade at the Luneta, the 93-year old general carried the flag he had raised in Kawit.

Post-American era

In 1950, President Elpidio Quirino appointed Aguinaldo as a member of the Council of State, where he served a full term. He returned to retirement soon after, dedicating his time and attention to veteran soldiers' interests and welfare.

In 1962, when the United States rejected Philippine claims for the destruction wrought by American forces in World War II, president Diosdado Macapagal changed the celebration of Independence Day from July 4 to June 12. Aguinaldo rose from his sickbed to attend the celebration of independence 64 years after he declared it.

Aguinaldo died on February 6, 1964, of coronary thrombosis at the Veterans Memorial Hospital in Quezon City. He was 94 years old. His remains are buried at the Aguinaldo Shrine in Kawit, Cavite. When he died, he was the last surviving non-royal head of state to have served in the nineteenth century.

Legacy

Filippino historians are ambiguous about Aguinaldo’s role in the history of the Philippines. He was the leader of the revolution and the first president of the first republic, but he is criticized for ordering the execution of Andres Bonifacio and for his possible involvement in the murder of Antonio Luna, and also for accepting an indemnity payment and exile in Hong Kong. Some scholars view him as an example of the leading role taken by members of the landowning elite in the revolution.[1]

Notes

- ↑ Keat Gin Ooi, Southeast Asia a Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor (1994).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aguinaldo, Emilio. A Second Look at America. New Yor, NY: R. Speller, 1957.

- Bain, David Haward. Sitting in Darkness: Americans in the Philippines. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1984. ISBN 0395352851

- Constantino, Renato and Letizia R. Constantino. A History of the Philippines from the Spanish Colonization to the Second World War. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010 (original 1975). ISBN 0853453942

- Lacsamana, Leodivico Cruz. Philippine History and Government. Quezon City, Philippines: Phoenix Pub. House, 2006. ISBN 9710618946

- Ooi, Keat Gin. Southeast Asia a Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2004. ISBN 1576077705

- Skillin, Don. Magdalo the Story of Emilio Aguinaldo: Revolutionary Hero of the Philippines. Baltimore, MD: PublishAmerica, 2006.

- Turot, Henri. Emilio Aguinaldo, First Filipino President, 1898-1901. Manila, Philippines: Foreign Service Institute, 1981.

External links

All links retrieved September 8, 2017.

- Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy Library of Congress.

- Emilio Aguinaldo Biography

- Works by Emilio Aguinaldo. Project Gutenberg.

| |||||

| Preceded by: Newly Established Preceded by Governor General of the Philippines-Diego de los Ríos (Government in Iloilo) |

President of the Philippines 1898–1901 |

Succeeded by: Abolished Governor General of the Philippines (American Occupation) U.S. Military Governor-General Wesley Merritt |

| ||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.