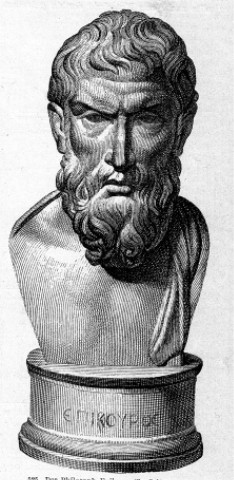

Epicurus

Epicurus (Epikouros or Ἐπίκουρος in Greek) (341 B.C.E. – 270 B.C.E.) was an ancient Greek philosopher, the founder of Epicureanism, one of the most popular schools of Hellenistic Philosophy. He taught that happiness was the ultimate goal of life, and that it could be achieved by seeking pleasure and minimizing pain, including the pain of a troubled mind. He encouraged the study of science as a way to overcome fear and ignorance and thus achieve mental calmness. He set up communities that tried to live by his philosophy. The Epicurean school remained active for several centuries and some of its teachings strongly influenced modern thinkers, particularly in the areas of civic justice and the study of physics.

Biography

Epicurus was born into an Athenian émigré family; his parents, Neocles and Chaerestrate, both Athenian citizens, were sent to an Athenian settlement on the Aegean island of Samos. According to Apollodorus (reported by Diogenes Laertius at X.14-15), he was born on the seventh day of the month Gamelion in the third year of the 109th Olympiad, in the archonship of Sosigenes (about February 341 B.C.E.). He returned to Athens at the age of 18 to serve in military training as a condition for Athenian citizenship. The playwright Menander served in the same age-class of the ephebes as Epicurus.

Two years later, he joined his father in Colophon when Perdiccas expelled the Athenian settlers at Samos after the death of Alexander the Great (c. 320 B.C.E.). He spent several years in Colophon, and at the age of 32 began to teach. He set up Epicurean communities in Mytilene, where he met Hermarchus, his first disciple and later his successor as head of the Athenian school; and in Lampsacus, where he met Metrodorus and Polyaenus, Metrodorus’ brother Timocrates, Leonteus and his wife Themista, Colotes, and Metrodorus’ sister Batis and her husband Idomeneus. In the archonship of Anaxicrates (307 B.C.E.-306 B.C.E.), he returned to Athens where he formed The Garden (Ho Kepus), a school named for the house and garden he owned about halfway between the Stoa and the Academy that served as the school's meeting place. These communities set out to live the ideal Epicurean lifestyle, detaching themselves from political society, and devoting themselves to philosophical discourse and the cultivation of friendship. The members of Epicurus’ communities lived a simple life, eating barley bread and drinking water, although a daily ration of half a pint of wine was allowed. The letters that members of these communities wrote to each other were collected by later Epicureans and studied as a model of the philosophical life.

Samos, Colophon, Mytilene and Lampsacus were all in Asia, and Epicurus actively maintained his ties with Asia all his life, even traveling from Athens to Asia Minor several times. This Asiatic influence is reflected in his writing style and in the broad ecumenical scope of his ideas.

Epicurus and his three close colleagues, Metrodorus (c. 331-278 B.C.E.), Hemarchus (his successor as head of the Athenian school) and Polyaenus (died 278 B.C.E.), known as “the Men” by later Epicureans, became the co-founders of Epicureanism, one of the three leading movements of Hellenistic thought.

Epicurus died in the second year of the 127th Olympiad, in the archonship of Pytharatus, at the age of 72. He reportedly suffered from kidney stones, and despite the prolonged pain involved, he is reported as saying in a letter to Idomeneus:

"We have written this letter to you on a happy day to us, which is also the last day of our life. For strangury has attacked me, and also a dysentery, so violent that nothing can be added to the violence of my sufferings. But the cheerfulness of my mind, which arises from their collection of all my philosophical contemplation, counterbalances all these afflictions. And I beg you to take care of the children of Metrodorus, in a manner worth of the devotion shown by the youth to me, and to philosophy" (Diogenes Laertius, X.22, trans. C. D. Yonge).

In his will Epicurus left the house and garden and some funds to the trustees of the school. He set aside funds to commemorate his deceased family and to celebrate his birthday annually and his memory monthly. He also freed his slaves and provided for the marriage of Metrodorus’ daughter.

The School

Epicurus' school had a small but devoted following in his lifetime. The primary members were Hermarchus, the financier Idomeneus, Leonteus and his wife Themista, the satirist Colotes, the mathematician Polyaenus of Lampsacus, and Metrodorus, the most famous popularizer of Epicureanism. This original school was based in Epicurus' home and garden. An inscription on the gate to the garden is recorded by Seneca in his Epistle XXI, “Stranger, here you will do well to tarry; here our highest good is pleasure.” Unlike the other Athenian schools of Plato and Aristotle, Epicurus’ school admitted women and slaves. Its members sought to avoid politics and public life, and lived simply, cultivating friendship and philosophical discourse.

The school's popularity grew and it became, along with Stoicism and Skepticism, one of the three dominant schools of Hellenistic philosophy, maintaining a strong following until the late Roman Empire. Only fragments of Epicurus’s prolific manuscripts remain, including three epitomes (Letter to Herodotus on physics, Letter to Pythocles on astronomy, and the Letter to Menoeceus on ethics), a group of maxims, and papyrus fragments of his masterwork, On Nature. Many of the details of Epicurean philosophy come to us from doxographers, secondary sources, and the writings of later followers. In Rome, Lucretius was the school's greatest proponent, composing On the Nature of Things, an epic poem, in six books, designed to recruit new members. The poem mainly deals with the Epicurean philosophy of nature. Another major source of information is the Roman politician and amateur philosopher Cicero, although he was highly critical of Epicureanism. An ancient source is Diogenes of Oenoanda (c. 2 C.E.) who composed a large inscription in stone at Oenoanda in Lycia.

Philosophy

Atomism

Epicurus' teachings represented a departure from the other major Greek thinkers of his period, and before, but was nevertheless founded on the atomism of Democritus. Everything that exists is either "body" or "space." Space includes absolute void, without which motion would not be possible. Body is made up of tiny indivisible particles, atoms, which can be further analyzed as sets of absolute “minima.” Atoms have only the primary properties of size, shape and weight, while combinations of atoms generate secondary properties like color. Atoms are constantly moving at a rapid pace, but large groups of atoms form stable compounds by falling into regular patterns of movement governed by three principles: weight (natural movement of falling in a straight line), collision (forced movement resulting from impact) and a “swerve,” or random free motion. This “swerve” initiates new patterns of movement and prevents determinism. Our world, and any other worlds that exist, is one of these complex groups of atoms, generated by chance. Everything that occurs is the result of the atoms colliding, rebounding, and becoming entangled with one another, with no purpose or plan behind their motions. Our world is not the creation of a divine will, and the gods are seen as ideal beings and models of ideal life, uninvolved with the affairs of man. Epicurus limited the number of sensible qualities by making the number of forms of the atoms finite, and to prevent combinations of atoms form resulting in infinite sensible qualities he developed a law of universal equilibrium of all the forces, or “isonomy.”

Epistemology

The Epicurean Canon, or rule (from a work, On the Criterion, or Canon) held that all sensations and representations (aesthêsis) are true and are one of three criteria of truth, along with the basic feelings of pleasure and pain (pathê), and prolepsis (concepts, or “a recollection of what has often been presented from without”). It is only when we begin to apply judgment to these criteria that error can occur. Using these three criteria we can infer the nature of a remote or microscopic object or phenomenon. If both prolepsis (naturally acquired concepts) and a number of examples from experience provide the same evidence that something is true, we are entitled to believe it true, on the grounds of ouk antimarturesis (lack of counter-evidence).

Epicurus concluded that the soul must be a body, made up of four types of atoms and consisting of two parts: one distributed through the physical body and able to experience physical sensations; and a separate part, the psyche, located in the chest, which is the seat of thought, emotion and will. Thin films continuously issue from all bodies and reach the psyche through the pores. Thought occurs when the images constituted by these films are perceived by the psyche. The psyche is free to continually seize only the images it needs from these films.

Sensual perception also takes place when films of atoms issued from the perceived object hit the sense organs.

Ethics

Epicurus’ philosophy is based on the principle that “all sensations are true.” Sensations that cause pleasure are good and sensations that cause pain are bad. The object of ethics is to determine the desired end, and the means necessary to achieve that end. Epicurus examined the animal kingdom and concluded that the ultimate end is “pleasure.” He defined two types of pleasure; a “kinetic” pleasure that actively satisfies the receiving sense organ, and “static” pleasure which is the absence of pain. Epicurus declared that “freedom from pain in the body and trouble in the mind” is the ultimate goal in achieving a happy life.

The modern-day terms “epicure” and “epicurean” imply extreme self-indulgence, but Epicurus was by no means a hedonist in the modern sense of the word. The highest pleasure, for both soul and body, is a satisfied state, “katastematic pleasure.” Self-indulgence and the enjoyment of luxuries may affect this state, but do not increase or heighten it. Instead, the effects of over-indulgence and the effort to accumulate wealth often lead to pain and vulnerability to fortune. Man’s primary goal should be to minimize pain. This can be accomplished for the body through a simple way of life that satisfies the basic physical needs, and this is relatively easy to obtain. Pain of the soul can be minimized through the study of physics (science), which eliminates fear and ignorance. Physical pain can be far outweighed by mental pleasure because it is temporary, while the pleasure of the mind ranges across time and space.

The members of Epicurus’ communities lived a simple life, eating barley bread and drinking water, although a daily ration of half a pint of wine was allowed. Epicurus taught that the way to achieve tranquility was to understand the limits of desire, and devoted considerable effort to the exploration of different types of desire.

Friendship

Another important component of happiness and satisfaction is friendship. The world of Epicurus’ time was one of violence and war, and it was necessary to ensure security in order to achieve pleasure. Epicurus advocated avoiding involvement with public life and the competition of society, to “live hidden.” A system of civic justice is important as a contract among human beings to refrain from harmful activity in order to maintain society. This contract is not absolute and can be revised as changing circumstances demanded it. In addition, it is necessary to enter into a private compact of friendship with like-minded individuals. This friendship, though entered into for utility, becomes a desirable source of pleasure in itself. Epicurus said, “for love of friendship one has even to put in jeopardy love itself,” and that a wise man, “if his friend is put to torture, suffers as if he himself were there.”

Death and Mortality

Epicurus recognized two great fears as causes of pain and mental anguish: fear of the gods and fear of death. He advocated the study of science to overcome these fears: “If we were not troubled by our suspicions of the phenomena of the sky and about death, and also by our failure to grasp the limits of pain and desires, we should have no need for natural science.” By using science to explain natural phenomena, it becomes clear that celestial phenomena are acts of nature and not acts of vengeance by the gods, who are unconcerned with human affairs. According to Epicurus, the soul and body both dissolve after death. There is no need to fear death while we are alive (and not dead), and once we die we cease to exist and can’t feel fear at all. If we understand that pleasure is perfect at each instant in our lives, and cannot be accumulated, we can see that “infinite time contains no greater pleasure than limited time,” and therefore it is vain to desire immortality.

God and Religion

Epicurus was one of the first Greek philosophers to challenge the belief that the cosmos was ruled by a pantheon of gods and goddesses who arbitrarily intervened in human affairs. He acknowledged the existence of the gods, but portrayed them as blissfully happy beings that would not disturb their tranquility by involving themselves in human affairs. He taught the gods were not even aware of human existence, and that they should be regarded only as examples of ideal existence. Epicurus saw “fear of the gods” as one of the great causes of mental anguish, and set out to overcome it by the study of science. His atomist theories held that the universe was a chance conglomeration of atoms, without the direction of any divine will. The Greeks believed the gods to be the cause of many “celestial phenomena,” such as storms, lightning strikes, floods and volcanic eruptions. Epicurus pointed out that there were natural explanations for all of these phenomena and that they should not be feared as the vengeance or punishment of the gods. Epicurus was also one of the first philosophers to discuss the concept of evil, saying that a benevolent will could not be watching over a universe filled with such misery and contradiction.

Some early Greek critics accused Epicurus of acknowledging the existence of the gods only to protect himself from persecution and a fate similar to that of Socrates. Because it minimized the importance of the gods and denied the existence of an afterlife, Epicureanism was viewed as anti-religious, first by the Greeks, then the Jews and Romans, and finally by the Christian church.

Civic Justice

Epicurus developed a theory of justice as a contract among the members of a community “neither to harm or be harmed.” Justice, like other virtues, has value only to the extent that it is useful to the community. Laws that do not contribute to the well being of the community cannot be considered just. Laws were needed to control the behavior of fools who might otherwise harm other members of the community, and were to be obeyed because disobedience would bring about punishment, or fear of punishment, and therefore, mental and physical pain.

Free Will

Epicurus’ writings about free will have been lost and a precise explanation of his theories is not available. He was very careful to avoid determinism in the construction of his atomic theory. In addition to the natural downward movement of atoms (weight or gravity) and the movement caused by collision, Epicurus introduced a third movement, the “swerve,” a random sideways movement. This “swerve” was necessary in order to explain why atoms began colliding in the first place, since without some kind of sideways movement all atoms would have just continued to travel downwards in parallel straight lines. It also avoided the possibility that all future events were pre-determined the moment atoms began to move, preserving human freedom and liberating man from fate.

The most well-known Epicurean verse, which epitomizes his philosophy, is lathe biōsas λάθε βιώσας (Plutarchus De latenter vivendo 1128c; Flavius Philostratus Vita Apollonii 8.28.12), meaning "live secretly," (live without pursuing glory or wealth or power).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Annas, Julia. 1993. The Morality of Happiness. Reprint ed. 1995. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195096525

- Cooper, John M. 1998. “Pleasure and Desire in Epicurus.” In John M. Cooper, Reason and Emotion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069105875X

- Frischer, Bernard. 1982. The Sculpted Word: Epicureanism and Philosophical Recruitment in Ancient Greece. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520041909

- Furley, David. 1967. Two Studies in the Greek Atomists. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gerson, L. P. and Brad Inwood (trans. and eds.). 1994. The Epicurus Reader. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 0872202410

- Gosling, J. C. B. and C. C. W. Taylor. 1982. The Greeks on Pleasure. New York: Oxford University Press (Clarendon Press). ISBN 0198246668

- Jones, Howard. 1992. The Epicurean Tradition London: Routledge. ISBN 0415075548

- Long, A. A. 1986. Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Skeptics. Second edition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520058089

- Long, A. A. & D. N. Sedley. 1987. The Hellenistic Philosophers Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521275563

- Mitsis, Phillip. 1988. Epicurus' Ethical Theory: The Pleasures of Invulnerability. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 080142187X

- O'Connor, Eugene Michael (trans.). 1993. The Essential Epicurus: Letters, Principal Doctrines, Vatican Sayings, and Fragments. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879758104

- Rist, John. 1972. Epicurus: An Introduction. New edition 1977. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052129200X

- Warren, James. 2002. Epicurus and Democritean Ethics: An Archaeology of Ataraxia Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521813697

External links

All links retrieved August 21, 2017.

- Epicurus.net - Epicurus and Epicurean Philosophy

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Entry for "Epicurus"

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Entry for "Epicurus"

- The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature - Karl Marx’s doctoral thesis.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.