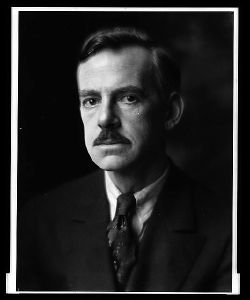

Eugene O'Neill

| Eugene O'Neill |

|---|

Eugene O'Neill, American playwright

|

| Born |

| October 16, 1888 New York, New York |

| Died |

| November 27, 1953 Boston, Massachusetts |

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was a Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning American playwright. More than any other dramatist, O'Neill introduced the dramatic Realism pioneered by the European playwrights Anton Chekhov, Henrik Ibsen, and August Strindberg into American theater. O'Neill was also famous for the bleak and tragic tone of his plays, which persistently examine the crushed hopes and dreams of the underprivileged.

O'Neill's plays are tragic, but in a new, modern sense of the term. Ancient tragedy depicted noble characters who nonetheless suffered from a tragic flaw. In the realistic theater of O'Neill and other modern dramatists, the characters possess little nobility—they are ordinary people, not of the type of King Oedipus—and are deeply flawed. Yet, for brief moments they are able to transcend their weaknesses to commit acts of "small" heroism and self-sacrifice. With the equalization of society that takes place in modernity, as each individual life becomes more important, less significance is ascribed to the grand hero who represents the whole society (Nietzsche bemoaned this democratic attitude). The other strand in O'Neil's plays is a sense of hopeless despair rooted in the loss of meaning in the modern world. Without a clear sense of meaning and purpose, in a world without the certainties of religion, his characters engage in the kind of self-destructive behavior that would eventually claim his own life.

O'Neill is often considered to be the most influential American playwright of the twentieth century. Just as Ibsen had done decades earlier for the European theater, O'Neill revolutionized the conception of what acceptable drama could be. He was a relentless examiner of the hopes—and failings—of everyday American life, and he sought to present all the aspects of his characters' lives in his plays. As a result of this, O'Neill became notorious for the shocking nature of many of his works; but the overpowering literary merit of his plays holds up past all controversy. Like Honore de Balzac, O'Neill sought to capture, in his plays, a microcosm of his times. His works reveal the all-to-frequent failures of human life, and in so doing redeems them.

Life

Eugene O'Neill's life was intimately connected to New London, Connecticut. His father was an Irish-born stage actor named James O'Neill, who had grown up in impoverished circumstances. His mother, Ella Quinlan O'Neill, was the emotionally fragile daughter of a wealthy father who died when she was seventeen. O'Neill's mother never recovered from the death of her second son, Edmund, who had died of measles at the age of two, and she became addicted to morphine as a result of Eugene's difficult birth.

O'Neill was born in a Broadway hotel room. Because of his father's profession, he spent his early years backstage at theaters and on trains as the family moved from place to place. When he was seven, O'Neill was sent to a Catholic boarding school where he found his only solace in books.

After being suspended from Princeton University for his frequent drinking, O'Neill spent several years as a sailor, during which time he suffered from depression and severe alcoholism. O'Neill lived for six years as a wanderer, working occasionally as a sailor and spending a great deal of time as an unemployed drifter in Buenos Aires, Liverpool, and New York City. O'Neill would later jokingly refer to this time of his life as his "real education."

O'Neill briefly found employment during this period as a writer for the New London Telegraph, dabbling in playwriting from time to time. It wasn't, however, until his experience at Gaylord Farms Sanatorium (where he was recovering from tuberculosis) that he experienced an epiphany and devoted his life to writing plays. O'Neill enrolled in the famous playwriting course taught by George Pierce Baker at Harvard University, spending 1914-15 writing prolifically, though he would later disown all his writings from this period. In 1916, O'Neill had his first big break, when he joined the Provincetown Players, a raggedy band of young writers, artists, and actors who had assembled in the tiny coastal village of Provincetown. Although many other writers wrote plays for the company to perform, O'Neill soon became their biggest attraction. During this period, O'Neill concentrated primarily on writing small, one-act plays that drew heavily from his experiences at sea. Bound East for Cardiff would become the most famous of these, and it would ultimately be O'Neill's first work to be performed in New York City, to rave reviews.

Following the success of Bound East for Cardiff, O'Neill moved back to New York and became a regular on the Greenwich Village literary scene, where he also befriended many radicals, most notably U.S. Communist Party founder John Reed. In 1920, O'Neill's first full-length play, Beyond the Horizon, was produced on Broadway. O'Neill would win a Pulitzer Prize for the play, and soon after he became a major literary celebrity. His productivity during this period was legendary; he wrote several plays a year, obsessively revising earlier drafts of plays for reproduction. In 1929, O'Neill moved to the Loire Valley of northwest France, where he lived in the Chateau du Plessis in St. Antoine-du-Rocher, Indre-et-Loire. Later, he moved to Danville, California, in 1937, living there until 1944.

In 1943, O'Neill disowned his daughter, Oona, for marrying the English actor/director/producer Charlie Chaplin when she was 18 and he was 54. He never saw her again.

After suffering from multiple health problems (including alcoholism) over many years, O'Neill ultimately began to suffer from a severe tremor in his hands which made it impossible for him to write. He attempted to write via dictation, but found it impossible to compose by that method; O'Neill never wrote another play for the remaining ten years of his life.

O'Neill died from the advanced stages of Parkinson's disease in room 401 of the Shelton Hotel in Boston, on November 27, 1953, at the age of 65. He was interred in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts.

Works

O'Neill's best-known plays include Desire Under the Elms, Strange Interlude (for which he again won the Pulitzer Prize), Mourning Becomes Electra, and his only comedy Ah, Wilderness! a wistful re-imagining of his own youth as he wished it had been. All of his plays tend to be marked by a darkness of tone—even his comic masterpiece Ah, Wilderness! verges dangerously close to becoming a tragedy—and a piercing degree of insight into the inner lives of his beleaguered characters. His late masterpiece The Iceman Cometh, produced in 1946, directly addressed the issues of doubt and religion which had cropped up throughout his oeuvre.

Although his written instructions had stipulated that it not be made public until 25 years after his death, in 1956, O'Neill's wife arranged for his autobiographical masterpiece, Long Day's Journey Into Night, to be published, and produced on stage to tremendous critical acclaim; it is now considered to be his finest play. Other posthumously-published works include A Touch of the Poet (1958) and More Stately Mansions (1967). Both A Touch of the Poet and More Stately Mansions were parts of a planned "dramatic epic" spanning 11 plays that would follow the life and times of a Boston family from the early 1800s to the present day. O'Neill wrote copious notes concerning the direction of the work, but the severe tremor in his hands prevented him from being able to complete anything other than these two fragments.

The Iceman Cometh

Summary

The Iceman Cometh, universally considered one of O'Neill's masterpieces, is set in Harry Hope's decidedly seedy Greenwich Village saloon and rooming house in 1912. The patrons are all dead-end alcoholics who spend every possible moment either drinking or trying to wheedle free drinks from Harry and the bartenders. They also all look forward to the regular visits of one of the bar's most famous patrons, the salesman Theodore Hickman, known to them as Hickey. Every time Hickey finishes a tour of his territory, which is apparently a wide expanse of the East Coast, he typically turns up at the saloon and starts a party. He buys drinks for everyone, regales them with jokes and stories, and goes on a bender of several days until his money runs out, only to start all over again. As the play opens, the regulars are expecting Hickey to turn up soon and plan to throw him a surprise birthday party. The entire first act introduces the various characters, showing them bickering among each other, showing just how drunk and delusional they truly are, all the while awaiting the arrival of Hickey.

When Hickey finally arrives, his behavior throws the other characters into turmoil. He appears as charismatic and cheerful as ever, but something has changed; he has sworn himself to sobriety, and he sees life clearly now as never before. He hectors his former drinking companions that they are meaninglessly clinging to dreams of positive change in their lives, while continuing to drown their sorrows exactly as before. Hickey wants the characters to cast away their delusions and embrace the hopelessness of their fates.

Themes

Following Hickey's return to the saloon, The Iceman Cometh concerns itself explicitly with all of O'Neill favorite themes: Redemption, failure, and fate. The play contains numerous allusions to the Bible, and as the play goes on it becomes clear the Hickey is meant as an allegorical figure for Christ. Yet Hickey, even after his "awakening," is no ordinary savior. Instead of imploring his companions to change their lives and escape the constant cycle of drinking and sorrow, Hickey—with all the fervent zealousness of a real religious prophet—encourages them to simply give in and become content with their own hopelessness. Instead of drinking their lives away, Hickey implores his friends to let go of their sorrows by simply giving up any hope of ever being any happier than they are. Continuing on with this rather ambiguous, almost nihilistic message, the play ends ambiguously, and the audience is left to wonder just how ironic a savior Hickey really is.

Selected works

- Bound East for Cardiff, 1916

- The Emperor Jones, 1920

- The Hairy Ape, 1922

- Anna Christie, 1922

- The Fountain, 1923

- Marco Millions, 1923-1925

- Desire Under the Elms, 1925

- Lazarus Laughed, 1925-1926

- The Great God Brown, 1926

- Strange Interlude, 1928

- Dynamo, 1929

- Mourning Becomes Electra, 1931

- Ah, Wilderness! 1933

- Days Without End, 1933

- The Iceman Cometh, written 1939, first performed 1946

- Long Day's Journey Into Night, written 1941, first performed 1956

- A Moon for the Misbegotten, 1943

- A Touch of the Poet, completed in 1942, first performed 1958

- More Stately Mansions, second draft found in O'Neill's papers, first performed 1967

- The Calms of Capricorn, published in 1983

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Black, Stephen A. Eugene O'Neill: Beyond Mourning and Tragedy. Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0300093993.

External links

All links retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site.

- An Electronic Eugene O'Neill Archive.

- Nobel autobiography.

- Eugene O'Neill's Photo & Gravesite.

|

1926: Grazia Deledda | 1927: Henri Bergson | 1928: Sigrid Undset | 1929: Thomas Mann | 1930: Sinclair Lewis | 1931: Erik Axel Karlfeldt | 1932: John Galsworthy | 1933: Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin | 1934: Luigi Pirandello | 1936: Eugene O'Neill | 1937: Roger Martin du Gard | 1938: Pearl S. Buck | 1939: Frans Eemil Sillanpää | 1944: Johannes Vilhelm Jensen | 1945: Gabriela Mistral | 1946: Hermann Hesse | 1947: André Gide | 1948: T. S. Eliot | 1949: William Faulkner | 1950: Bertrand Russell |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.