Fan (implement)

A fan is a device used to induce airflow and generally made from broad, flat surfaces which revolve or oscillate. The most common applications of fans are for creature comfort, ventilation, or gaseous transport for industrial purposes. The simplest kind of fans are leaves or flat objects, waved to produce a more comfortable atmosphere.

Typical applications include ornamental decorations, climate control, cooling systems, personal wind-generation (such as an electric table fan), ventilation (like an exhaust fan), winnowing (such as separating chaff of cereal grains), removing dust (like the sucking in a vacuum cleaner), drying (usually in addition to heat) and to provide draft for a fire. It is also common to use electric fans as air fresheners, by attaching fabric softener sheets to the protective housing. This causes the fragrance to be carried into the surrounding air.

History

Etymology

In Old English "fann" referred to a basket or shovel for winnowing, or separating the chaff from grain by means of a current of air. It was a loan from the Latin word "vannus," a word with the same meaning, derived from "ventus" ("wind") or a related root (such as "vates"). In the sense of "device for moving air" the word is first attested 1390, the hand-held version is first recorded in 1555.

Ancient

The history of fans stretches back thousands of years. Since antiquity, fans have possessed a dual function — status symbol and useful ornament. In the course of their development, fans have been made of a variety of materials and have often included decorative artwork. The simplest fans are leaves or flat objects, waved to produce a cooler atmosphere. These rigid or folding hand-held implements have been used for cooling, for air circulation, as ceremonial devices, and as sartorial accessories throughout the world from ancient times. They are still widely used.

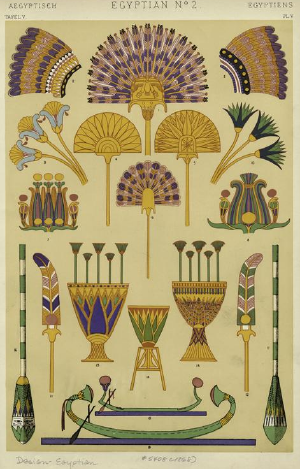

The earliest known fans are called 'screen fans' or 'fixed leaf fans.' These were manipulated by hand to cool the body, to produce a breeze, and to ward off insects. Such early fans usually took the form of palm tree leaves. Some of the earliest known fans have come from Egyptian tombs. Early Assyrians and Egyptians employed slaves and servants to manipulate the fan. In Egyptian reliefs, fans were of the rigid type. Tutankhamun's tomb possessed gold fans with ostrich feathers, matching depictions on tomb walls. Long-handled, disk-shaped fans were carried by attendants in ancient times and were associated with regal and religious ceremonies. They had handles or sticks attached to a rigid leaf or to feathers.

Plumage of birds has been used in fans, such as those of the Egyptians and Native American Indians, for both practical and ceremonial uses. In the ancient Americas, the Aztec, Maya, and South American cultures used bird feathers in their fans. Among the Aztec fans were depictions of merchants in illustrations of trades. The use of various feather types in these fans had a religious connotation. The Paracas people of South America (modern Peru) have left numerous examples of ancient feather fans among their mummies. In India, the Hindi term for a fan is pankha (a derivative of "a feather" or "a bird's wing").

Pictorial evidence records that the Greeks, the Etruscans, and the Romans used fans as cooling and ceremonial devices. In Greece, linen was stretched over leaf-shaped frames. In Rome, gilded and painted wooden fans were used. Roman ladies throughout the empire used circular fans. Chinese sources link the fan with mythical and historical characters.

Asia

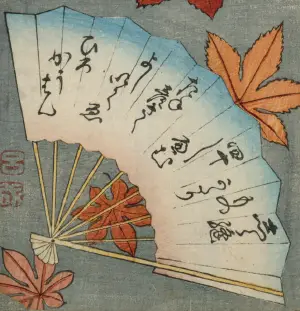

Fans were often symbolic of social status in the Far East; individuals carried specific fans in accordance with their gender and status. For example, the Akomeogi (or Japanese folding fan; Hiôgi), originating in the sixth century, were fans held by aristocrats of the Heian period when formally dressed. They were made by tying thin stripes of hinoki (or Japanese cypress) together with thread. The number of strips of wood differed according to the person's rank.

Variations of this folding fan were then taken China in the ninth century. It came into fashion during the Ming dynasty between the years of 1368 and 1644, and Hangzhou became a center of folding fan production. Akomeogi fans are used today by Shinto priests in formal costume and in the formal costume of the Japanese court (they can be seen used by the Emperor and Empress during coronation and marriage) and are brightly painted with long tassels.

In China, screen fans were more traditionally more common, and used throughout society. The earliest known Chinese fans are a pair of woven bamboo side-mounted fans from the second century B.C.E.. The Chinese character for "fan" (扇) is etymologically derived from a picture of feathers under a roof. The Chinese fixed fan, pien-mien, means 'to agitate the air.' Printed fan leaves and painted fans are done on a paper ground. The paper was originally hand made and displayed the characteristic watermarks. Machine-made paper fans, introduced in the nineteenth century, are smoother with an even texture.

The Chinese dancing fan was developed in the seventh century, and the management of the fan became a highly regarded feminine art. The Chinese form of the hand fan was a row of feathers mounted in the end of a handle. The Mai Ogi (or Chinese dancing fan) has ten sticks and a thick paper mount showing the family crest. Chinese painters crafted many fan decoration designs. The slats, of ivory, bone, mica, mother of pearl, sandalwood, or tortoise shell, were carved and covered with paper or fabric. Folding fans have "montures" which are the sticks and guards. The leaves are usually painted by craftsman.

Fans were also used as a weapon - called the iron fan, or tiě shān in Chinese, tessen in Japanese, used by Samurai warriors for battle signals, also as a lethal weapon in close combat. Simple Japanese paper fans are sometimes known as "harisens." In Japanese current pop culture, Harisens are featured frequently in animation and graphic novels as weapons. Folding fans (Japanese "sensu," Chinese: "shān zi") continue to be important cultural symbols and popular tourist souvenirs in East Asia.

Europe

In Europe, during the Middle Ages, the fan was absent. The West's earliest fan is a flabellum (or ceremonial fan), which dates to the sixth century. Hand fans were reintroduced to Europe in the thirteenth and fourteenth century. Fans from the Middle East were brought back by Crusaders. In the fifteenth century, Portuguese traders brought fans to Europe from China and Japan. Fans became generally popular.

In the 1600s the folding fan, introduced from China, became popular in Europe. These fans are particularly well displayed in the portraits of the high-born women of the era. Queen Elizabeth I of England can be seen to carry both folding fans decorated with pom poms on their guardsticks as well as the older style rigid fan, usually decorated with feathers and jewels. These rigid style fans often hung from the skirts of ladies, but of the fans of this era it is only the more exotic folding ones which have survived. The folding fans of the 15th century that are found in museums today have either leather leaves with cut out designs forming a lace-like design or a more rigid leaf with inlays of more exotic materials like mica. One of the characteristics of these fans is the rather crude bone or ivory sticks and they way the leather leaves are often slotted onto the sticks rather than glued as with later folding fans. Yet despite the relative crude methods of construction, folding fans were at this era high status, exotic items on par with elaborate gloves as gifts to royalty.

In the seventeenth century the rigid fan which was seen in portraits of the previous century had fallen out of favor as folding fans gained dominance in Europe. Fans started to display well painted leaves, often with a religious or classical subject. The reverse side of these early fans also started to display elaborate flower designs. The sticks are often plain ivory or tortoiseshell, sometimes inlaid with gold or [silver]] pique work. The way the sticks sit close to each other, often with little or no space between them is one of the distinguishing characteristics of fans of this era.

In 1685 the Edict of Nantes was revoked in France. This caused large scale immigration from France to the surrounding Protestant countries (such as England) of many fan craftsman. This dispersion in skill is reflected in the growing quality of many fans from these non-French countries after this date.

In the eighteenth century, fans reached a high degree of artistry and were being made throughout Europe often by specialized craftsmen, either in leaves or sticks. Folded fans of lace, silk, or parchment were decorated and painted by artists. Fans were also imported from China by the East India Companies at this time. Around the middle 1700s, inventors started designing mechanical fans. Wind-up fans (similar to wind-up clocks) were popular in the 1700s. In the nineteenth century in the West, European fashion caused fan decoration and size to vary.

It has been said that in the courts of England, Spain and elsewhere fans were used in a more or less secret code. These fan languages were a way to cope with the restricting social etiquette. This is now used for marketing by fan makers like Duvelleroy in London.

Mechanical development

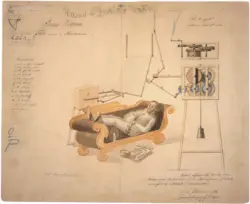

The first recorded mechanical fan was the punkah fan used in the Middle East in the 1500s. It had a canvas covered frame that was suspended from the ceiling. Servants, known as punkah wallahs, pulled a rope connected to the frame to move the fan back and forth.

The Industrial Revolution in the late 1800s introduced belt-driven fans powered by factory waterwheels. Attaching wooden or metal blades to shafts overhead that were used to drive the machinery, the first industrial fans were developed. One of the first workable mechanical fans was built by A. A. Sablukov in 1832. He called his invention—a kind of a centrifugal fan—an "Air Pump." Centrifugal fans were successfully tested inside coal mines and factories in 1832-1834. When Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla introduced electrical power in the late 1800s and early 1900s for the public, the personal electrical fan was introduced. Between 1882 and 1886, Dr. Schuyler Skaats Wheeler developed the two-bladed desk fan, a type of personal electric fan. It was commercially marketed by the American firm Crocker & Curtis electric motor company. In 1882, Philip H. Diehl introduced the electric ceiling fan. Diehl is considered the father of the modern electric fan. In the late 1800s, electric fans were used only in commercial establishments or in well-to-do households. Heat-convection fans fueled by alcohol, oil, or kerosene were common around the turn of the 20th century.

In the 1920s, industrial advances allowed steel to be mass-produced in different shapes, bringing fan prices down and allowing more homeowners to afford them. In the 1930s, the first art deco fan was designed. Before this fan, called the Silver Swan, most household fans were fairly plain. In the 1950s, fans were manufactured in colors that were bright and eye catching. Central air conditioning in the 1960s brought an end to the golden age of the electric fan. In the 1970s, Victorian-style ceiling fans became popular.

In the twentieth century, fans have become utilitarian. During the 2000s, fan aesthetics have become a concern to fan buyers. The fan is part of everyday life in the Far East, Japan, and Spain (among other places). Electric fans have been largely replaced by air conditioners in households and offices, even though electric fans consume much less energy than air conditioners.

Mechanical devices

Mechanically, a fan can be any revolving vane or vanes used for producing currents of air. Fans produce air flows with high volume and low pressure, as opposed to gas compressors which produce high pressures at a comparatively low volume. Fans are useful for moving large quantities of air, which are best suited for applications such as winnowing grain or blowing a fire, cooling and ventilation purposes, and in conjunction with a heat source for heating and drying. A fan blade will often rotate when exposed to an air stream, and devices that take advantage of this, such as anemometers and wind turbines often have designs similar to that of a fan.

Mechanical revolving blade fans are made in a wide range of designs. In a home you can find fans that can be put on the floor or a table, or hung from the ceiling, or are built into a window, wall, roof, chimney, etc. They can be found in electronic systems such as computers where they cool the circuits inside, and in appliances such as hair dryers and space heaters. They are also used for cooling in air-conditioning systems, and in automotive engines, where they are driven by belts or by direct motor. Fans create a wind chill but do not lower temperatures directly.

Types

There are three main types of fans used for moving air: axial, centrifugal (also called radial) and cross flow (also called tangential). The axial-flow fans have blades that force air to move parallel to the shaft about which the blades rotate. Axial fans blow air across the axis of the fan, linearly, hence their name. This is the most commonly used type of fan, and is used in a wide variety of applications, ranging from small cooling fans for electronics to the giant fans used in wind tunnels.

The centrifugal fan has a moving component (called an impeller) that consists of a central shaft about which a set of blades form a spiral pattern. Centrifugal fans blow air at right angles to the intake of the fan, and spin (centrifugally) the air outwards to the outlet. An impeller rotates, causing air to enter the fan near the shaft and move perpendicularly from the shaft to the opening in the scroll-shaped fan casing. A centrifugal fan produces more pressure for a given air volume, and is used where this is desirable such as in leaf blowers, air mattress inflators, and various industrial purposes. They are typically noisier than comparable axial fans.

The cross flow fan has a squirrel cage rotor (a rotor with a hollow center and axial fan blades along the periphery). Tangential fans take in air along the periphery of the rotor, and expel it through the outlet in a similar fashion to the centrifugal fan. Cross flow fans give off an even airflow along the entire width of the fan, and are very quiet in operation. They are comparatively bulky, and the air pressure is low. Cross flow fans are often used in air conditioners, automobile ventilation systems, and for cooling in medium-sized equipment such as photocopiers. The action of a fan or blower causes pressures slightly above atmospheric, which are called "plenums."

Fans typically go along with electric motors. An electric motor's poor low speed torque and powerful high speed torque are a natural match for a fan's load. Fans are often attached directly to the motor's output, with no need for gears or belts. The electric motor is either hidden in the fan's center hub or extends behind it. For big industrial fans, 3-phase asynchronous motors are commonly used. Smaller fans are often powered by shaded pole AC motors, or brushed or brushless DC motors. AC-powered fans usually use mains voltage, while DC-powered fans use low voltage, typically 24 V, 12 V or 5 V. Cooling fans for computer equipment exclusively use brushless DC motors, which produce much less electromagnetic interference.

In machines which already have a motor, the fan is often connected to this rather than being powered independently. This is commonly seen in cars, large cooling systems and winnowing machines.

- Table fan

Basic elements of a typical table fan include the fan blade, base, armature and lead wires, motor, blade guard, motor housing, oscillator gearbox, and oscillator shaft. The oscillator is a mechanism that motions the fan from side to side. The axle comes out on both ends of the motor, one end of the axle is attached to the blade and the other is attached to the oscillator gearbox. The motor case joins to the gearbox to contain the rotor and stator. The oscillator shaft combines to the weighted base and the gearbox. A motor housing covers the oscillator mechanism. The blade guard joins to the motor case for safety.

Among collectors, electro-mechanical fans are rated according to their condition, size, age, and number of blades. Four-blade designs are the most common. Five-blade or six-blade designs are rare. The materials from which the components are made, such as brass, are important factors in fan desirability.

- Ceiling fan

A fan suspended from the ceiling of a room is a ceiling fan.

- Solar powered fan

Electric fans used for ventilation may be powered by solar panels instead of mains current. This is an attractive option because once the capital costs of the solar panel have been covered, the resulting electricity is free. In addition, electricity is always available when the sun is shining and the fan needs to run.

A typical example uses a detached 10 watt, 12x12 inch (30x30 cm) solar panel and is supplied with appropriate brackets, cables, and connectors. It can be used to ventilate up to 1250 square feet (100 m²) of area and can move air at up to 800 cubic feet per minute (400 L/s). Because of the wide availability of 12 V brushless DC electric motors and the convenience of wiring such a low voltage, such fans usually operate on 12 volts.

The detached solar panel is typically installed in the spot which gets most of the sun light and then connected to the fan mounted as far as 20 to 25 feet (6 to 7 m) away. Other permanently-mounted and small portable fans include an integrated (non-detachable) solar panel.

Gas turbine fan

The low pressure compressor in a turbofan engine is often called a fan. Typically, these units absorb thousands of horsepower, the power being provided by the expansion of hot combustion gases through the low pressure turbine.

- Front fan

The fan is usually located at the front of the turbomachinery, immediately downstream of the air intake.

Modern civilian turbofans usually have a single fan stage, that is a row of rotating rotor blades, followed by a row of stationary exit guide vanes (or stators).

Military turbofans (fans fitted to a combat aircraft) usually have two or more fan stages, the first stage, again, normally being a rotor followed by a stator assembly.

- Aft fan

Several turbofans feature an aft fan, where the fan rotor blades are mounted radially outwards of the (LP) turbine rotor blades. This dispenses with the need for an (LP) shaft. In an early example, General Electric bolted a fan/turbine unit to the rear of a J79 turbojet, to convert it into the CJ805 turbofan.

The unusual General Electric CF700 turbofan engine was also developed as an aft-fan engine with a 2.0 bypass ratio. This was derived from the T-38 Talon and the Learjet General Electric turbojet (2,850 lbf or 12,650 N) to power the larger Rockwell Sabre 75/80 version of the Sabreliner aircraft, as well as the Dassault Falcon 20 with about a 50 percent increase in thrust (4,200 lbf or 18,700 N). The CF700 was the first small turbofan in the world to be certificated by the Federal Aviation Administration. There are now over 400 CF700 aircraft in operation around the world, with an experience base of over 10 million service hours. The CF700 turbofan engine was also used to train Moon-bound astronauts in the Apollo Project as the powerplant for the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV).

The GE36 unducted fan (UDF) Demonstrator used a similar arrangement to convert an F404 mixed exhaust turbofan into a propfan.

- Supersonic fan

Early gas turbine fans rotated at subsonic tip speeds, to avoid the generation of shock waves in the airflow. Modern fans, however, often rotate at supersonic tip speeds, and exploit the shock waves. Some advanced designs can generate a pressure ratio of more than 2.2:1 in a single stage, although 1.8:1 is more typical.

- Supersonic through-flow fan

Although supersonic fans rotate at a supersonic tip speed, the axial flow is subsonic. However, some experimental devices have demonstrated supersonic axial flow. All the speed lines on the resulting fan map (or characteristic) are virtually horizontal, unlike those of more conventional units.

- Variable pitch fan

Several ultra-high bypass ratio turbofan demonstrator engines (such as the SNECMA M45SD-02, the engine inside the Rolls-Royce) have incorporated variable pitch fans, much like the variable pitch propellers on a turboprop engine. Varying the pitch of the rotor blades improves the low flight speed handling of the low pressure ratio fan unit, without the need to resort to a variable area cold or mixed flow nozzle. Reverse thrust down to zero aircraft speed is also practical.

- Variable geometry fan

Some multi-stage, high pressure ratio, fans on military turbofan engines (such as the F404) incorporate variable geometry . The variability is usually confined to the inlet guide vanes. Although the leading edge of the vane is static, a piano-type hinge allows the trailing edge to be adjusted in pitch, to redirect the airflow onto the first rotor. VIGV's enhance the surge margin of the fan in the mid-flow region.

- Propfan

Some ultra-high bypass ratio turbofans dispense with the fan nacelle and have an unducted fan rotor. The fan blades, which resemble scimitars, are especially shaped to work efficiently at flight speeds up to about Mach 0.75. General Electric demonstrated a propfan engine, called the GE36 UDF, in the 1980s.

- Overhung fan

Turbojets and early turbofans used the inlet guide vanes to support the front bearing of the (LP) compressor/fan rotor assembly. Today, the fans used in turbofan engines are often to an overhung design, where the fan rotor is cantilevered out forward, beyond the front bearing. This facilitates the removal of the inlet guide vanes. Consequently, the fan rotor blades are the first aerofoils encountered by the engine airflow.

- Snubbered fan

Prior to the introduction of wide chord fan blades, fan blades fitted to turbofan engines often featured snubbers. These are protuberances that stick-out at right angles to the fan aerofoil, somewhere between mid-span and blade tip. The snubbers on adjacent fan blades butt-up against each other, in a peripheral sense, and improve the vibration characteristics of the blade.

Wire lacing (e.g., Pegasus) is an alternative approach.

- Wide chord fan

As might be expected, snubbers reduce the aerodynamic efficiency of fan aerofoils. Rolls-Royce pioneered a more efficient alternative: wide chord fan blades. The increased blade chord (i.e., width) is used to enhance the vibration characteristics.

Wide chord first went into service in the RB311-535E4 for the Boeing 757 in 1984 and have been a feature of the RB211/Trent/V2500 engine family ever since. Potential weight increases are usually offset by making the blades hollow. Other engine manufacturers have now introduced wide chord fans.

- Swept fan

Engine manufacturers are beginning to introduce so-called swept fan blades, which should yield benefits in aerodynamic efficiency and noise.

Other kinds of fans

- In a fan heater, a fan (or blower) blows cool air past a heating element, heating the air (forced convection). It has a fan wheel with vanes fixed on a rotating shaft enclosed in a case or chamber, to create a blast of air (the fan blast) for forge purposes.

- A Japanese war fan is a weapon made to look like a folding fan.

- In automobiles, a mechanical fan, driven with a belt and pulley off the engine's crankshaft, or an electric fan switched on/off by a thermo switch is used to blow or suck air through a coolant filled radiator, to prevent the engine from overheating.

- A fan is also a small vane or sail that is used to keep the large sail of a smock windmill always in the direction of the wind.

See also

- Centrifugal fan

- Computer fan

- Fan death

- The Fan Museum in Greenwich (Greenwich, London)

- Heat exchanger

- Turbine

- Whole house fan

- Wind turbine

- Windmill

- Window fan

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexander, Helene. 2001. The Fan Museum. Tempe, AZ: Third Millennium Publishing. ISBN 0954031911.

- Armstrong, Nancy. 1984. Book of Fans. New York: Smithmark Publishing. ISBN 0831709529

- Armstrong, Nancy. 1984. Fans. Souvenir Press.

- Bennett, Anna G. 1988. Unfolding beauty: The art of the fan: the collection of Esther Oldham and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. London, UK: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0878462791.

- Cowen, Pamela. 2003. A Fanfare for the Sun King: Unfolding Fans for Louis XIV. Tempe, AZ: Third Millennium Publishing. ISBN 1903942209.

- Gitter, Kurt A. 1985. Japanese fan paintings from western collections. New Orleans, LA: New Orleans Museum of Art. ISBN 089494021X.

- Hart, Avril & Emma Taylor. 1998. Fans. (V & A Fashion Accessories Series). London, UK: V & A Publications. ISBN 1851772138.

- Hutt, Julia & Helene Alexander. 1992. Ogi: A History of the Japanese Fan. Chicago, IL: Art Media Resources; Bilingual edition. ISBN 1872357083.

- Irons, Neville John. 1982. Fans of Imperial China. Hong Kong: Kaiserreich Kunst Ltd. ASIN B000R0HVP0.

- Mayor, Susan. 1995. A Collector's Guide to Fans. Bracken Books, ASIN: B000KPJAS8

- Mayor, Susan. 1991. The Letts Guide to Collecting Fans. London: Charles Letts. ISBN 1852381280

- North, Audrey. 1985. Australia's fan heritage. Boolarong Publications. ISBN 0864390017.

- Qian, Gonglin. 2004. Chinese Fans: Artistry and Aesthetics (Arts of China, #2). San Francisco, CA: Long River Press. ISBN 1592650201.

- Rhead, G. Wooliscroft. 1910. The History of the Fan. London, UK: Paul Kegan.

- Roberts, Jane. 2006. Unfolding Pictures: Fans in the Royal Collection. London, UK: Royal Collection. ISBN 1902163168.

External links

All links retrieved March 26, 2017.

- Hand Fans

- The Fan Circle International - charitable society established to promote interest in and knowledge of the fan.

- Fan Association of North America.

- La Place de l'Eventail - history of fans; text is mostly in French.

- Galerie Le Curieux, Paris - picture of fans from the 17th-19th century, as well as contemporary, art deco fans; text is in French.

- Fans in the 16th and 17th Centuries.

- Ceiling Fans

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.