Fig wasp

| Fig wasps | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

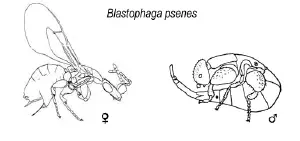

Blastophaga psenes

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

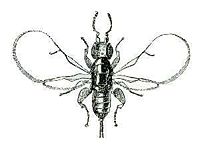

Fig wasp is the common name for wasps of the family Agaonidae, which pollinate the blossoms of fig trees or are otherwise associated with fig trees. Many of the wasps currently placed together within this family may not be considered to be closely related in an evolutionary sense, but are placed together because of their shared association with fig trees. Adult fig wasps are commonly no larger than about 5 millimeters (.2 inches) in length.

Typically, one species of fig wasp is capable of fertilizing the flowers of only one of the nearly 1000 species of fig tree. The fig tree's fruit-body, commonly called a fig, comprises a protective outer layer, the syconium, and hundreds of tiny fig flowers blooming inside it. The interior of the syconium provides a secure incubator for fig wasp eggs, and habitat and nutrition for the wasps’ larvae and young adults, while the flowers inside the syconium receive from the fig wasps the benefit of being pollinated by the adult that enters the fig to lay her eggs inside it. Before the newly matured adult female leaves her incubator, she needs to pick up pollen from male flowers that she will then carry into the new syconium that she finds in which to lay her eggs.

Fig trees exhibit remarkably varied reproductive patterns, which provide the backdrop for the complex, symbiotic interplay between fig wasps and figs. The dependence of the fig flowers on the pollination services of the fig wasp, and the dependence of the fig wasp on the habitat and nutrition services of the fig fruit-bodies exemplifies the particular kind of symbiotic relationship known as obligate mutualism. Each species depends on the other for its survival. Together they provide a striking example of cooperation in a biological system.

Overview and description

Fig wasps are members of the order Hymenoptera, one of the largest orders of insects, comprising the ants, bees, wasps, and sawflies, among others. As insects, hymenopterans are characterized by having a body separated into three parts (head, thorax, and abdomen), with one pair of antennae on the head, three pairs of jointed legs attached to the thorax, and the abdomen being divided into 11 segments and lacking any legs or wings. As true insects, hymenopterans also are distinguished from all other arthropods in part by having ectognathous, or exposed, mouth parts.

Adult hymenopterans typically have two pairs of wings with reduced venation. The hindwings are connected to the forewings by a series of hooks called hamuli. Hymenopterans have compound eyes and the antennae are long, multisegmented, and covered with sense organs (Grzimek et al. 2004). Females have an ovipositor—an organ used for laying eggs—that in some species of wasps, ants, and bees has been modified for a defense function rather than an egg-laying function.

Among the Agaonidae, the female is the more typically appearing insect, while the males are mostly wingless. In many cases the males' only tasks are to mate with the females while still within the fig syconium and to chew a hole for the females to escape from the fig interior. (In other cases the males die inside the syconium after they mate.) This is the reverse of Strepsiptera and the bagworm, where the male is a normally appearing insect and the female never leaves the host.

Classification

Hymenopterans are divided into the two suborders of Apocrita and Symphyta. Fig wasps belong to the suborder Apocrita along with the bees, ants, and other wasps (Gzimek et al. 2004). Broadly defined, a wasp is any insect of the order Hymenoptera and suborder Apocrita that is not a bee or ant. In species belonging to Aprocrita, the first abdominal segment is firmly attached to the metathorax and usually separated by a narrow waist (petiole) (Grzimek et al. 2004).

As presently defined, the family Agaonidae, which comprises the fig wasps, is polyphyletic, that is, it includes several unrelated lineages whose similarities are based upon their shared association with figs. Since classification seeks to arrange species according to shared lineage, efforts are underway to resolve the matter, and move a number of constituent groups to other families, particularly the Pteromalidae and Torymidae. Thus, the number of genera in the family is in flux. Probably only the Agaoninae should be regarded as belonging to the Agaonidae, while the Sycoecinae, Otitesellinae, and Sycoryctinae might be included in the Pteromalidae. Placement of the Sycophaginae and Epichrysomallinae remains uncertain.

Figs and fig wasps

Fig is the common name given to any vine, shrub, or tree in the genus Ficus of the mulberry family, Moraceae. (The term also is used for the edible, round to oval, multiple fruit of the common fig, Ficus carica, which is of commercial importance. The fruit of many other species are edible, though not widely consumed.) In addition to the common fig, Ficus carica, the most well known species, other examples of figs include the banyans and the sacred fig (Peepul or Bo) tree.

The Ficus genus is characterized by hundreds to thousands of tiny flowers occurring in the inside of a fleshy, fruit-like body (a syconium). The fruit-like body or receptacle is commonly thought of as a fruit, but it is properly a false fruit or multiple fruit, in which the flowers and seeds grow together to form a single mass. Technically, a fig fruit would be one of the many mature, seed-bearing flowers found inside one receptacle.

In other words, a fig "fruit" is derived from a specially adapted type of inflorescence (structural arrangement of flowers). The fleshy, fruit-like body commonly called the "fruit" technically is a specialized structure, or accessory fruit, called a syconium: an involuted (nearly closed) receptacle with many small flowers arranged on the inner surface. Thus, the actual flowers of the fig are unseen unless the fig is cut open. In Chinese, the fig is called "fruit without flower."

The syconium often has a bulbous shape with a small opening (the ostiole) at the apex that allows access by pollinators. The flowers are pollinated by the very small fig wasps that crawl through the opening in search of a suitable place to reproduce (lay eggs). Without this pollinator service, fig trees cannot reproduce by seed. In turn, the flowers provide a safe haven and nourishment for the next generation of wasps.

Fig inflorescences in the at least 1000 species of figs occur in both bisexual and unisexual forms and with significant variation within those two types. About half of the species are monoicous, with both male and female flowers occurring inside each of their fruit-bodies, and about half are dioicous, having separate male dominant(but bisexual)-flowering and female-flowering trees.

Inside each of the "fruits" of many of the monoicous species are three kinds of flowers: male, short female, and long female. Female fig wasps can reach the ovaries of short female flowers with their ovipositors, but cannot reach the ovaries of long female flowers. Thus, the short female flowers grow wasps and the long female flowers, if pollinated, grow seeds. By the time fig fruit-bodies of this type have developed seeds, they also contain dead fig wasps almost too tiny to see. The male flowers sharing the same syconium with the female flowers mature a few weeks after the female flowers, roughly when the new crop of wasps would be due to mature. The females of the new crop of wasps are the ones that need to pick up the pollen from the male flowers and carry it out of the receptacle and into the next fruit-body whose interior flowers are blooming.

In the half of the fig species that are dioicous the female trees bear only female flowers while the fruit-bodies of the male trees often are bisexual (hermaphrodite) but functionally male. All the native fig trees of the American continent are monoicous, as well as the species F. benghalensis, F. microcarpa, F. religiosa, F. benjamina, F. elastica, F. lyrata, F. sycomorus, and F. macrophylla. On the other hand, the common fig (Ficus carica) is a dioicous plant, as well as, F. aspera, F. auriculata, F. deltoidea, F. pseudopalma, and F. pumila.

The bisexual or hermaphrodite common figs are called caprifigs, from the Caprinae subfamily or goats, as in fit for eating by goats (sometimes called "inedible"). The other one is female, as the male flower parts fail to develop; this produces the "edible" fig. Fig wasps grow in caprifigs but not in the female syconiums because the female flower is too long for the wasp to successfully lay her eggs in them. Nonetheless, the wasp pollinates the flower with pollen from the fig it grew up in. When the wasp dies, it is broken down by enzymes inside the fig. Fig wasps are not known to transmit any diseases harmful to humans.

There typically is only one species of wasp capable of fertilizing the flowers of each species of fig, and therefore plantings of fig species outside of their native range results in effectively sterile individuals. For example, in Hawaii, some 60 species of figs have been introduced, but only four of the wasps that fertilize them have been introduced, so only four species of figs produce viable seeds there. The common fig Ficus carica is pollinated only by Blastophaga psenes.

However, there are several commercial and ornamental varieties of fig that are self-fertile and do not require pollination; these varieties are not visited by fig wasps.

Life cycle

As hymenopterans, fig wasps are holometabolus insects, which means that they undergo complete metamorphosis in which the larvae differ markedly from the adults. Insects that undergo holometabolism pass through a larval stage, then enter an inactive state called pupa, and finally emerge as adults (imago).

The life cycle of the fig wasp is closely intertwined with that of the fig tree they inhabit. The wasps that inhabit a particular tree can be loosely divided into two groups; pollinating and non-pollinating. The pollinating variety forms a mutually beneficial symbiosis with the tree, whereas the non-pollinating variety is parasitic. Both life cycles, however, are very similar.

Though the lives of individual species differ, a general fig wasp life cycle is as follows. In the beginning of the cycle, a mature female pollinator wasp enters a receptacle ("fruit") through a small natural opening, the ostiole. It passes through the mouth of the fig, which is covered in male flowers. She then deposits her eggs in the cavity, which is covered in female flowers, by oviposition. Forcing her way through the ostiole, she often loses her wings and most of her antennae. In depositing her eggs, the female also deposits pollen that she picked up from her original host fig. This pollinates some of the female flowers on the inside surface of the fig and allows them to mature. After pollination, there are several species of non-pollinating wasps that deposit their eggs before the figs harden. These wasps act as parasites to either the fig or the pollinating wasps. As the fig develops, the wasp eggs hatch and develop into larvae.

After going through the pupal stage, the mature male’s first act is to mate with a female. The males of many species lack wings and are unable to survive outside the fig for a sustained period of time. After mating, many species of the male wasps begin to dig out of the fig, creating a tunnel for the females which allows them to escape.

Once out of the fig, the male wasps quickly die. The females leave the figs, picking up pollen as they do. They then fly to another tree of the same species where they deposit their eggs and allow the cycle to begin again.

Genera

Genera currently included in Agaonidae according to the Universal Chalcidoidea Database:

|

|

|

|

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Grzimek, B., D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M. C. McDade. 2004. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0787657883.

- Rasplus, J.-Y., C. Kerdelhuse, I. Clainche, and G. Mondor. 1998. Molecular phylogeny of fig wasps. Agaonidae are not monophyletic. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences (III) 321(6):517-527

- Ronsted, N., G. D. Weiblen, J. M. Cook, N. Salamin, C. A. Machado, and V. Savoainen. 2005. 60 million years of co-divergence in the fig-wasp symbiosis Proceeding of the Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences 272(1581): 2593-2599. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

External links

All links retrieved April 7, 2017.

- Video: Interaction of figs and fig wasps Multi-award-winning documentary.

- Figs and fig wasps

- Images of fig wasps on Morphbank, a biological image database

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.