Flight

Flight is the process by which an object achieves sustained movement through the air, as in the case of aircraft, or beyond Earth's atmosphere, as in the case of spaceflight. When flying through the air, heavier-than-air craft depend primarily on lift that is generated aerodynamically, while lighter-than-air objects depend on buoyancy. By contrast, spacecraft depend on thrust that is generated when rocket engines burn fuel.

Historical highlights

In eighth century Cordoba, Ibn Farnas studied the dynamism of flight and carried out a number of experiments. After one of his flights he fell on his back and commented that he now understood the role of the tail when a bird alighted on the ground. He told his close friends that birds normally land on the root of the tail, which did not happen on that occasion, hence a reference to the missing tail.[1] In his book “The Story of Civilisation,” Durant quoted Al-Makkari who mentioned that Ibn Farnas indeed constructed a flying machine.[2] However, he did not elaborate on how the machine worked, nor whether it was the one Ibn Farnas used, nor what happened to it.

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the best-known early students of flight. He made many prototypes of parachutes, wings, and ornithopters.

Physics

There are different approaches to flight. If an object has a lower density than air, then it is buoyant and can float in the air without using energy. A heavier than air craft, known as an aerodyne, includes flighted animals and insects, fixed-wing aircraft and rotorcraft. Because the craft is heavier than air, it must use the force of lift to overcome its weight. The wind resistance caused by the craft moving through the air is called drag and is overcome by propulsive thrust except in the case of gliding.

Some vehicles also use thrust for flight, for example rockets and Harrier Jump Jets.

Relevant forces

Forces relevant to flight are[3]

- Propulsive thrust (except in gliders)

- Lift: Created by the reaction to an airflow

- Drag: Created by aerodynamic friction

- Weight (a result of gravity acting on a mass)

- Buoyancy: For lighter-than-air flight

These forces must be balanced for stable flight to occur.

The stabilization of flight angles (roll, yaw and pitch) and the rates of change of these can involve horizontal stabilizers (such as a "tail"), ailerons and other movable aerodynamic devices which control angular stability i.e. flight attitude (which in turn affects altitude, heading).

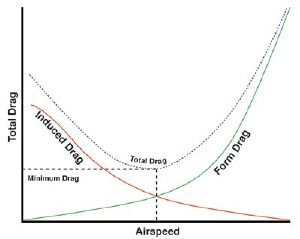

Lift to drag ratio

When lift is created by the motion of an object through the air, this deflects the air, and this is the source of lift. For sustained level flight, lift must be greater than weight.

However, this lift inevitably causes some drag also, and it turns out that the efficiency of lift creation can be associated with a lift/drag ratio for a vehicle; the lift/drag ratios are approximately constant over a wide range of speeds.

Lift to drag ratios for practical aircraft vary from about 4:1 up to 60:1 or more. The lower ratios are generally for vehicles and birds with relatively short wings, and the higher ratios are for vehicles with very long wings, such as gliders.

Thrust to weight ratio

If thrust-to-weight ratio is greater than one, then flight can occur without any forward motion or any aerodynamic lift being required.

If the thrust-to-weight ratio is greater than the lift-to-drag ratio then takeoff using aerodynamic lift is possible.

Energy efficiency

To create thrust to push through the air to overcome the drag associated with lift takes energy, and different objects and creatures capable of flight vary in the efficiency of their muscles, motors and how well this translates into forward thrust.

Propulsive efficiency determines how much thrust propeller and jet engines gain from a unit of fuel.

Power to weight ratio

All animals and devices capable of sustained flight need relatively high power to weight ratios to be able to generate enough lift and/or thrust to achieve take off.

Types

Animal

The most successful groups of living things that fly are insects, birds, and bats. The extinct Pterosaurs, an order of reptiles contemporaneous with the dinosaurs, were also successful flying animals.

Bats are the only mammals capable of sustaining level flight. However, several mammals, such as flying squirrels, are able to glide from tree to tree using fleshy membranes between their limbs. Some can travel hundreds of meters in this way with very little loss of height. Flying frogs use greatly enlarged webbed feet for a similar purpose, and there are flying lizards that employ their unusually wide, flattened rib-cages to the same end. Certain snakes also use a flattened rib-cage to glide, with a back and forth motion much the same as they use on the ground.

Flying fish can glide using enlarged wing-like fins, and have been observed soaring for hundreds of meters using the updraft on the leading edges of waves. The longest recorded flight of a flying fish was 45 seconds.[4]

Most birds fly, with some exceptions. The largest birds, the ostrich and emu, are earthbound, as were the now-extinct dodos and the Phorusrhacids, which were the dominant predators of South America in the Cenozoic period. The non-flying penguins have wings adapted for use under water and use the same wing movements for swimming that most other birds use for flight. Most small flightless birds are native to small islands, and lead a lifestyle where flight would confer little advantage.

Among living animals that fly, the wandering albatross has the greatest wingspan, up to 3.5 meters (11.5 ft); the great bustard has the greatest weight, topping at 21 kilograms (46 pounds).[5]

Among the many species of insects, some fly and some do not.

Mechanical

Mechanical flight is the use of a machine to fly. These machines include airplanes, gliders, helicopters, autogyros, airships, balloons, ornithopters, and spacecraft. Gliders provide unpowered flight. Another form of mechanical flight is parasailing, where a parachute-like object is pulled by a boat.

In the case of an airplane, lift is created by the wings; the shape of the wings of the airplane are designed specially for the type of flight desired. There are different types of wings: tempered, semi-tempered, sweptback, rectangular, and elliptical. An aircraft wing is sometimes called an airfoil, which is a device that creates lift when air flows across it.

Supersonic

Supersonic flight is flight faster than the speed of sound, which is known as Mach 1. However, because supersonic airflow differs from subsonic airflow, an aircraft is said to be flying at supersonic speed only if the airflow around the entire aircraft is supersonic, which occurs around Mach 1.2 on typical designs.

Supersonic flight is associated with the formation of shock waves that form a sonic boom that can be heard from the ground, and is frequently startling. This shockwave takes quite a lot of energy to create and it makes supersonic flight generally less efficient than subsonic flight at about 85 percent of the speed of sound.

Hypersonic

Speeds greater than 5 times the speed of sound are often referred to as hypersonic. During hypersonic flight, the heat generated by compression of the air due to motion through the air causes chemical changes to the air. Hypersonic flight is achieved by spacecraft, such as the Space Shuttle and Soyuz, during reentry into the atmosphere.

In religion, mythology and fiction

In religion, mythology, and fiction, human or anthropomorphic characters are sometimes said to have the ability to fly. Examples include angels in the Hebrew Bible, Daedalus in Greek mythology, and Superman in comics. Two other popular examples are Dumbo, an elephant created by Disney, who used his ears to fly, and Santa Claus, whose sleigh is pulled by flying reindeer. Other non-human legendary creatures, such as some dragons and Pegasus, are also depicted with an ability to fly.

The ability to fly may come from wings or other visible means of propulsion, from superhuman or god-like powers, or may be simply left unexplained.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Al-Makkari (ed.), Nafh Al-Teeb Volume 4 (Dar Al-Fikre, EG, 1986).

- ↑ Will Durant, The Story of Civilisation vol. 13 (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1967).

- ↑ NASA, Four forces on an airplane. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ↑ BBC, Flying fish. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ↑ Trumpeter Swan Society, The Trumpeter Swan Society—Swan Identification. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, David, and Scott Eberhardt. Understanding Flight. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2000. ISBN 0071363777.

- Anderson, John. Introduction to Flight. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2007. ISBN 0073529397.

- Tennekes, Henk. The Simple Science of Flight: From Insects to Jumbo Jets. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997. ISBN 0262700654.

External links

All links retrieved April 13, 2017.

- See how it flies: a new spin on the perceptions, procedures, and principles of flight.

- 'Birds in Flight and Aeroplanes' by Evoluntionary Biologist and trained Engineer John Maynard-Smith Freeview video provided by the Vega Science Trust.

- How airplanes fly.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.