France

| République française French Republic |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity) |

||||||

| Anthem: "La Marseillaise" |

||||||

| Location of Metropolitan France (dark green) – on the European continent (light green dark grey) – in the European Union (light green) |

||||||

| Territory of the French Republic in the world |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Paris 48°51.4′N 2°21.05′E | |||||

| Official languages | French | |||||

| Demonym | French | |||||

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic | |||||

| - | President | Emmanuel Macron | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Édouard Philippe | ||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||

| - | Upper House | Senate | ||||

| - | Lower House | National Assembly | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | Francia | 486 (Unification by Clovis) | ||||

| - | West Francia | 843 (Treaty of Verdun) | ||||

| - | Current constitution | 5 October 1958 (5th Republic) | ||||

| EU accession | 25 March 1957 | |||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total[1] | 674,843 km² (41st) 260,558 sq mi |

||||

| - | Metropolitan France | |||||

| - IGN[2] | 551,695 km² 213,010 sq mi |

|||||

| - Cadastre[3] | 543,965 km² 210,026 sq mi |

|||||

| Population | ||||||

| (2017 estimate) | ||||||

| - | Total[1] | 67,013,000[4] (20th) | ||||

| - | Metropolitan France | 64,880,000 (22nd) | ||||

| - | Density[5] | 116/km² (89th) 301/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $2.835 trillion[6] (10th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $43,760[6] (26th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $2.583 trillion[6] (7th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $39,869[6] (22nd) | ||||

| Gini (2013) | 30.1 | |||||

| Currency | Euro,[7] CFP franc[8] ( EUR, XPF) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET[5] (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST[5] (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .fr[9] | |||||

| Calling code | [[+331]] | |||||

| 1 | The overseas regions and collectivities form part of the French telephone numbering plan, but have their own country calling codes: Guadeloupe +590; Martinique +596; French Guiana +594, Réunion and Mayotte +262; Saint Pierre and Miquelon +508. The overseas territories are not part of the French telephone numbering plan; their country calling codes are: New Caledonia +687, French Polynesia +689; Wallis and Futuna +681 | |||||

| 2 | Spoken mainly in overseas territories | |||||

France, officially the French Republic, is a country whose metropolitan territory is located in Western Europe and that also comprises various overseas islands and territories located in other continents. French people often refer to Metropolitan France as L'Hexagone (The "Hexagon") because of the geometric shape of its territory.

The French Republic is a unitary semi-presidential republic with more than 200 years of democratic traditions, and about 500 years as a unified European state.

France ranks among the world's most influential centers of cultural development. It is the place of origin of the French language and civil law forms the basis of the legal systems of many countries. The nation was the center of the French Empire, and the birthplace of the French Revolution. French political and social ideas influenced Europe and America.

Christianity took root in France in the second century, and became so firmly established that France obtained the title "Eldest daughter of the Church," and the French would adopt this as justification for calling themselves "the Most Christian Kingdom of France." Later France produced a series of philosophers noted for radical skepticism, and atheism.

Geography

The name "France" comes from Latin Francia, which literally means "land of the Franks" or "Frankland." France is bordered by Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Monaco, Andorra, and Spain. It is also linked to the United Kingdom by the Channel Tunnel, which passes underneath the English Channel. Corsica lies off the Mediterranean coast.

While Metropolitan France is located in Western Europe, France also has a number of territories in North America, the Caribbean, South America, the southern Indian Ocean, the Pacific Ocean, and Antarctica. These territories have varying forms of government ranging from overseas department to overseas collectivity.

Metropolitan France covers 213,010 square miles (551,695 square kilometers), making it the largest country in area in the European Union, being only slightly larger than Spain, or slightly less than the size of Texas, in the United States.

France possesses a wide variety of landscapes, from coastal plains in the north and west to mountain ranges of the Alps in the southeast, the Massif Central in the southcentral and Pyrenees in the southwest. At 15,770 feet (4807 meters) above sea-level, the highest point in Western Europe, Mont Blanc, is situated in the Alps on the border between France and Italy.

Metropolitan France lies within the northern temperate zone. The north and northwest have a temperate climate, however, a combination of maritime influences, latitude and altitude produce a varied climate in the rest of the country. In the southeast a Mediterranean climate prevails. In the west, the climate is predominantly oceanic with a high level of rainfall, mild winters and cool summers. Inland the climate becomes more continental with hot, stormy summers, colder winters and less rain. The climate of the Alps and other mountainous regions are mainly alpine in nature with the number of days with temperatures below freezing over 150 per year and snowcover lasting for up to six months.

France has extensive river systems such as the Loire, the Garonne, the Seine and the Rhône, which divides the Massif Central from the Alps and flows into the Mediterranean Sea at the Camargue. The lowest point in France is 6.5 feet (two meters) below sea level.

A major divide, running from the southern end of the Vosges down the eastern and southeastern edge of the Massif Central to the Noire Mountains, is the source of most of the rivers of the larger, western part of the country, including the Seine and the Loire. Other main rivers are the Garonne, flowing from the Pyrenees, and the Rhône and the Rhine, originating in the Alps.

France has forests of chestnut and beech in the Massif Central, juniper and dwarf pine in the sub-alpine zone, with pine forests and various oaks in the south. Eucalyptus from Australia and dwarf pines abound in Provence, while olive trees, vines, mulberry, fig trees, as well as laurel, wild herbs, and maquis scrub grow in the Mediterranean area.

Brown bear, chamois, marmot, and alpine hare live in the Pyrenees and the Alps. Polecats, marten, wild boar, and various deer live in the forests. Hedgehog, shrew, fox, weasel, bat, squirrel, badger, rabbit, mouse, otter, and beaver are common. Birds include warblers, thrushes, magpies, owls, buzzards, and gulls. There are storks in Alsace, eagles and falcons in the mountains, pheasants and partridge in the south. Flamingos, terns, buntings, herons, and egrets are found in the Mediterranean zone. The rivers contain eels, pike, perch, carp, roach, salmon, and trout, while lobster and crayfish are found in the Mediterranean Sea.

France's natural resources includes coal, iron ore, bauxite, fish, timber, potash, and zinc. Natural hazards include flooding, avalanches, and forest fires. Environmental issues include forest damage from acid rain, air pollution from industrial and vehicle emissions, water pollution from urban wastes, and agricultural run-off.

Paris, the capital city, is situated on the River Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region. The city of Paris had an estimated population of 2,153,600 within its administrative limits in 2006. The Paris urban area extends well beyond the administrative city limits and has a population of 9.93 million. An important settlement for more than two millennia, Paris is today one of the world's leading business and cultural centers, and its influence in politics, education, entertainment, media, fashion, science and the arts all contribute to its status as one of the world's major global cities.

History

Pre-history

The Neanderthals, the earliest Homo sapiens to occupy Europe, are thought to have arrived there around 300,000 B.C.E., but seem to have died out by about by 30,000 B.C.E. The earliest modern humans—Cro-Magnons—entered Europe (including France) around 40,000 years ago during a long interglacial period, when Europe was relatively warm, and food was plentiful. They brought with them sculpture, engraving, painting, body ornamentation, music and the painstaking decoration of utilitarian objects. Some of the oldest works of art in the world, such as the cave paintings at Lascaux in southern France, are datable to shortly after this migration.

During the Neolithic period (ca. 4500 B.C.E.–1700 B.C.E.), which is characterized by the adoption of agriculture, the development of pottery and more complex, larger settlements, there was an expansion of peoples from southwest Asia into Europe. From the Neolithic to the Bronze Age (2000-800 B.C.E.), Indo-European and Proto-Celtic peoples spread across Western Europe. By 800 B.C.E., the Hallstatt people, who were warriors and shepherds from the Alpine region, introduced the techniques of working with iron. In the fifth century B.C.E., the La Tène culture gradually transformed into Celtic culture.

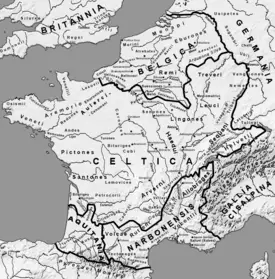

Gaul

Covering large parts of modern day France, Belgium, and northwest Germany, Gaul was inhabited by many Celtic tribes whom the Romans referred to as Gauls and who spoke the Gaulish language. On the lower Garonne the people spoke an archaic language related to Basque, the Aquitanian language. The Celts founded cities such as Lutetia Parisiorum (Paris) and Burdigala (Bordeaux) while the Aquitanians founded Tolosa (Toulouse).

Long before any Roman settlements, Greek navigators settled in what would become Provence. The Phoceans founded important cities such as Massalia (Marseilles) and Nicaea (Nice), bringing them in to conflict with the neighboring Celts and Ligurians. The Celts themselves often fought with Aquitanians and Germans, and a Gaulish war band led by Brennus invaded Rome circa 390 or 387 B.C.E. following the Battle of the Allia. When Hannibal Barca fought the Romans, he recruited several Gaulish mercenaries who fought on his side at Cannae. It was this Gaulish participation that caused Roman Republic to annex Provence in 121 B.C.E. Despite Gaulish opposition led by Vercingetorix, the Overking of the Warriors, Gauls succumbed to the Roman onslaught; the Gauls had some success at first at Gergovia, but were ultimately defeated at Alesia 52 B.C.E.

Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul consisted of an area of provincial rule in the Roman Empire, in modern day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and western Germany. Roman control of the area lasted for 600 years. The Roman Empire began its takeover of what was Celtic Gaul in 121 B.C.E., when it conquered and annexed the southern reaches of the area. Julius Caesar completed the task by defeating the Celtic tribes in the Gallic Wars of 58-51 B.C.E.. The Romans displaced populations in order to prevent local identities to become a threat to Roman control. The Romans divided Gaul into several provinces, and founded cities such as Lugdunum (Lyon) and Narbonensis (Narbonne). The Gauls eventually adopted Roman speech (Latin, from which the French language evolved) and Roman culture. The Roman administration finally collapsed as remaining troops were withdrawn southeast to protect Italy. Between 455 and 475, the Visigoths, the Burgundians, and the Franks assumed power in Gaul.

Clovis unites Franks

Clovis I (c. 466 – 511) succeeded his father Childeric I in 481 as King of the Salian Franks, who occupied the area west of the lower Rhine, with their centre around Tournai and Cambrai along the modern frontier between France and Belgium. In 486, Clovis I defeated Syagrius at Soissons and subsequently united most of northern and central Gaul under his rule. In 496, Clovis converted to Roman Catholicism, as opposed to the Arianism common among Germanic peoples, at the instigation of his wife, the Burgundian Clotilda, a Catholic. He was baptized in the Cathedral of Rheims. This act was of immense importance in the subsequent history of France and Western Europe in general, for Clovis expanded his dominion over almost all of the old Roman province of Gaul (roughly modern France). He is considered the founder both of France (which his state closely resembled geographically at his death) and the Merovingian dynasty which ruled the Franks from the mid-fifth to the mid-eighth century. Merovingian rule was ended by a palace coup in 751 when Pippin the Short formally deposed Childeric III, beginning the Carolingian monarchy.

Christianity took root in the second century and third century, and became so firmly established by the fourth and fifth centuries that Saint Jerome wrote that Gaul was the only region "free from heresy." France obtained the title "Eldest daughter of the Church" (La fille ainée de l'Église), and the French would adopt this as justification for calling themselves "the Most Christian Kingdom of France."

Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire

The Carolingian dynasty was a Frankish noble family with its origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the seventh century. The name "Carolingian" itself comes from the Latin spelling of Charles Martel, (686-741)—Carolus Martellus—who defeated the Moors at the Battle of Tours in 732. The greatest Carolingian monarch was Charlemagne (742 or 747 to 814), a champion of Christianity and supporter of the papacy. Charlemagne fought the Slavs south of the Danube, annexed southern Germany, and subdued and converted pagan Saxons in the north-west. Charlemagne had himself crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III at Rome in 800, an event which revived the Roman imperial tradition in the west, and set a precedent for the dependence of the emperors on papal approval.

He is often seen as the Father of Europe and is an iconic figure, instrumental in defining European identity. His was the first truly imperial power in the West since the fall of Rome. Latin was the official language of the court and the Church, although the West Franks in Gaul adopted the Latinate vernacular that became French. East Franks and other Germanic people spoke various languages that became German. Carolingian rulers encouraged missionary work among the Germans. Non-Frankish Germans, however, retained much pagan belief beneath their newly acquired faith.

Empire divided

Charlemagne's third son Louis the Pious (778–840) was Emperor and King of the Franks from 814 to his death in 840. Under Frankish custom, all the king’s possessions, including the royal title, were divided among his sons, a practice that often resulted in civil war. The surviving adult Carolingians fought a three-year civil war ending in the Treaty of Verdun (843), which divided the empire among Charlemagne's three grandsons. One received West Francia (modern France), another acquired the imperial title and a territory extending from the North Sea to Italy, while the third, Louis the German (804-876), received East Francia (modern Germany). The Treaty of Mersen (870) divided the middle kingdom, with Lotharingia going to East Francia and the rest to West Francia. In 881, Charles the Fat (839-888) of East Francia, heir of Louis the German, received the imperial title. Six years later he was deposed by Arnulf of Carinthia (850-899), a bastard child of a legitimate Carolingian king, the last Carolingian emperor.

The Vikings and Normandy

Under the Carolingians, the kingdom was ravaged by Viking raiders. In this struggle some important figures such as Count Odo of Paris and his brother King Robert rose to fame and became kings. This emerging dynasty, called the Robertines, was the predecessor of the Capetian Dynasty, who were descended from the Robertines. Led by Rollo, the Vikings had settled in Normandy and were granted the land first as counts and then as dukes by King Charles the Simple. The people that emerged from the interactions between Vikings and the mix of Franks and Gallo-Romans became known as the Normans.

The Capetians

The Carolingians ruled France until 987, when Hugh Capet, Duke of France and Count of Paris, was crowned king. He was recorded to be recognized king by the Gauls, Bretons, Danes, Aquitanians, Goths, Spanish and Gascons. Hugh had his son Robert crowned, as Robert II in 996. His son, Henry, became King in 1031. The Capetians eventually passed the crown through a direct male line for more than three centuries, from 987 until 1328.

The French kingdom was very decentralized. If the king ventured outside of his own territory, he risked being captured by his vassals. In the late eleventh century, vassals William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, and Hugh the Great, abbot of Cluny, were more powerful than the Capetian King Philip I (who reigned 1060-1108).

Philip’s successor, Louis VI (who reigned 1108-1137), consolidated royal power in the Île-de-France, a region centering on Paris, by suppressing feudal opposition. In 1137, he arranged for his son, the future Louis VII, to marry Eleanor, heiress to the Duchy of Aquitaine, thereby gaining control of extensive territories between the River Loire and the Pyrenees Mountains. Louis VII was well served by a competent advisor, Abbot Suger, whose vision of construction became known as the Gothic Architecture during the later Renaissance.

But the marriage was not agreeable to Eleanor, adultery was alleged, and she had not produced a male heir, so the marriage was annulled 1152. Eleanor married Henry Plantagenet, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy, who in 1154 became King of England as Henry II. Aquitaine passed to the English Crown, and the regions controlled by Henry II in France (the Angevin Empire) exceeded those of his feudal lord, Louis VII.

Later Capetians

Philip II Augustus (1165-1223) was King of France from 1180 until his death. Philip was one of the most successful medieval French monarchs in expanding the royal demesne and the influence of the monarchy. He broke up the great Angevin Empire and defeated a coalition of his rivals at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. He reorganized the government, bringing financial stability to the country and thus making possible a sharp increase in prosperity. His reign was popular with ordinary people because he checked the power of the nobles and passed some of it on to the growing middle class. Philip Augustus founded the Sorbonne university and made Paris a city of scholars.

His son Louis VIII led a successful campaign that resulted in the extension of the royal domain south to the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Louis IX (1215–1270), commonly Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 to his death, on a Crusade when he was struck down by disease and died while attacking Tunis. He is the only canonized king of France. He established the Parlement of Paris. Philip III (1245-1285), called "the Bold," was declared king at the age of 25 when his father died, and also died on a Crusade. He arranged for the marriage of his son to the heiress of Champagne, adding that county to royal possessions.

Philip IV (1268-1314), called "the Fair" was so powerful that he could name popes and emperors, unlike the early Capetians. Costly policies led him to try to tax the clergy, and this in turn brought him into sharp conflict with Pope Boniface VIII. In 1305, Philip secured the election of a French pope, Clement V. The papal court moved from Rome to Avignon in 1309, and Philip was cleared of any charges of impropriety in their dealings with Boniface. Philip strengthened the royal government, and was the first to summon the Estates-General, an assembly of the different classes of French subjects, but his high-handed methods lost public respect. His three sons -—Louis X, Philip V, and Charles IV—each held the throne successively, and all died without male heirs

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a conflict between France and England, lasting 116 years from 1337 to 1453. It was fought primarily over claims by the English kings to the French throne. On the death of Charles IV, the French crown passed to Philip IV’s nephew, Philip of Valois, who reigned as Philip VI from 1328 to 1350. The English King Edward II had married the daughter of Philip IV Isabella of France without succession problems, but her son Edward III (who reigned 1327-1377) put forward a claim in 1337 to the French throne as the legitimate grandson of Philip the Fair and the sole surviving male heir according to the law of primogeniture.

The Hundred Years' War was punctuated by several brief and two lengthy periods of peace before it finally ended in the expulsion of the English from France, with the exception of the Calais. Thus, the war was in fact a series of conflicts and is commonly divided into three or four phases: the Edwardian War (1337-1360), the Caroline War (1369-1389), the Lancastrian War (1415-1429), and the slow decline of English fortunes after the appearance of Joan of Arc. During this war, France evolved politically and militarily. Humiliating defeats of Poitiers (1356) and Agincourt (1415) forced the French nobility to realize they could not stand just as armored knights without an organized army. Charles VII established the first French standing army.

Black Death

The Black Death bubonic plague, one of the most deadly pandemics in human history, entered France via Marseille in 1348, and engulfed the country in two years, killing up to one-third of the population. The plague recurred in 1361, 1362, 1369, 1372, 1382, 1388, and 1398. Children were especially vulnerable. Obsession with death pervaded, and fanatical religious movements spread. Peasants caught between high prices, and landlords who tried to increase production and freeze wages rebelled, the most famous and widespread being the Jacquerie uprising of 1358. The Estates-General, the assembly of clergy, nobles, and commoners first summoned by Philip IV and used as a form for the king to present policy, gained in power.

Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (Jeanne d'Arc) (1412-1431) was a fifteenth century national heroine of France. Joan asserted that she had visions from God which told her to recover her homeland from English domination late in the Hundred Years' War. The uncrowned Charles VII of France sent her to the siege at Orléans (1428-1429) as part of a relief mission. She gained prominence when she overcame the dismissive attitude of veteran commanders and lifted the siege in only nine days. Several more swift victories led to Charles VII's coronation at Reims and settled the disputed succession to the throne. A politically motivated trial convicted her of heresy and she was burnt at the stake when she was only 19 years old. The judgment was broken by the Pope and she was declared innocent and a martyr 24 years later.

Renaissance France

By 1500, France evolved from a feudal country to an increasingly centralized state organized around a powerful absolute monarchy that relied on the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings and the explicit support of the established Church. The Renaissance writer François Rabelais (probably born in 1494) helped to shape the French language as a literary language. During the sixteenth century the French kingdom began to claim North American territories as colonies. Jacques Cartier was one of the great explorers who ventured deep into American territories during the sixteenth century. The largest group of French colonies became known as New France, and several cities such as Quebec City, Montreal, Detroit and New Orleans were founded by the French.

Francis I

Francis I (1494 - 1547), who is considered to be France's first Renaissance monarch, significantly increased both the power and the prestige of the Crown. He regarded himself as the monarchy’s sole lawmaker and never called the Estates-General. He was a patron of the arts and learning, and buildings surviving from his reign show the power and wealth of the monarchy. France engaged in the long Italian Wars (1494-1559), which marked the beginning of early modern France. Francis I was captured at Pavia in 1525 by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and later freed after granting concessions. The French monarchy allied with the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Admiral Barbarossa captured Nice in August 1543 and handed it down to Francis I.

During the sixteenth century, the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs were the dominant power in Europe. Charles Quint, as Count of Burgundy, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Aragon, Castile and Germany (among many other titles) encircled France. The Spanish Tercio was used with great success against French knights and remained undefeated for a long time. Finally on January 7, 1558, the Duke of Guise seized Calais from the English.

The Reformation

Lutheranism was introduced in France after about 1520. Initially, King Francis I was tolerant of religious reformers, but after the Affair of the Placards in 1534, in which notices appeared in the streets denouncing the Papal Mass, he began to view Protestants as a threat and openly moved against them. One French Protestant, John Calvin (1509-1564), created the doctrine and the institutions of French Protestantism. He found refuge in Geneva, where he came to hold great influence on the reform movement. During the reign of Henry II (1547-1559), Calvinism gained numerous converts in France among the French nobility, the middle class, and the intelligentsia. Although Huguenots accounted for only a small fraction of the French population, the great wealth and influence that many of them possessed began to cause bitterness. In 1559, delegates from 66 Calvinist congregations in France met secretly at Paris in a national synod which drew up a confession of faith and a book of discipline. Thus was organized the first national Protestant church of France.

Wars of religion

The French Wars of Religion, (1562 to 1598) were a series of conflicts in France fought between Catholics and Huguenots (Protestants) from the middle of the sixteenth century to the Edict of Nantes in 1598, including civil infighting as well as military operations. In addition to the religious elements, they involved a struggle for control over the ruling of the country between the powerful House of Guise (Lorraine) and the Catholic League, on the one hand, and the House of Bourbon on the other.

Renewed Catholic reaction headed by the powerful duke of Guise, led to a massacre of Huguenots at Vassy in 1562, starting the first of the French Wars of Religion, during which English, German, and Spanish forces intervened on the side of rival Protestant and Catholic forces. In the most notorious incident, thousands of Huguenots were murdered in the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572. The Wars of Religion culminated in the War of the Three Henrys in which Henry III assassinated Henry de Guise, leader of the Spanish-backed Catholic league, and the king was murdered in return. Following this war Henry III of Navarre became king of France as Henry IV and enforced the Edict of Nantes (1598), which granted a degree of religious toleration to Protestants.

Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu

Religious conflicts resumed under Louis XIII (1601-1643) when Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642), the effective ruler of France for 18 years from 1624, forced Protestants to disarm. This conflict ended in the Siege of La Rochelle (1627-1628), in which Protestants and their English supporters were defeated. The following Peace of Alais confirmed religious freedom yet dismantled the Protestant defenses.

As a result of Richelieu's work, Louis XIII became one of the first exemplars of an absolute monarch. Under Louis XIII, the French nobility was firmly kept in line behind their King, and the political and military privileges granted to the Huguenots by his father were retracted (while their religious freedoms were maintained). Richelieu had executed several eminent and dangerous nobles and demolished castles that could be used as centers of resistance to break the political power of the nobility. Richelieu divided the country into 30 new administrative districts and appointed a royal officer to control each.

Richelieu joined the Thirty Years War on the side of the Catholic Habsburgs in 1636 because it was the national interest, but imperial Habsburg forces invaded France, ravaged Champagne, and threatened Paris. Richelieu died in 1642 and was replaced by Mazarin, while Louis XIII died one year later and was succeeded by Louis XIV, then aged five years. The French forces won a decisive victory at Rocroi (1643), and the Spanish army was decimated. The Truce of Ulm (1647) and the Peace of Westphalia (1648) brought an end to the war.

Louis XIV

Louis XIV (1638-1715), known as Louis the Great or the Sun King, ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1643, a few months before his fifth birthday, but did not assume actual personal control of the government until the death of his First Minister Jules Cardinal Mazarin, in 1661. Louis would remain on the throne till his death just prior to his 77th birthday in 1715. Louis established an absolute state structure early, with a number of councils to advise him and to carry out his instructions. He gave the potentially dangerous nobility ceremonial court positions, leaving them no time for political activity. The government's active promotion of commerce kept the wealthy bourgeoisie happy. The king could appoint bishops, thus keeping control of an obedient clergy, who provided the theological justification of the divine right of Louis XIV. Louis built a great palace at Versailles, patronized the arts, founded the Academy of Fine Arts and the French Academy in Rome, supported authors with pensions, appointed a superintendent of music to raise standards, and established the Academy of Science.

Louis’s minister for commerce and finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, subsidized industries, limited foreign competition, developed colonial markets for French traders, rebuilt the navy, and built roads, bridges, and canals. But the costs of Louis’s wars unraveled much of Colbert’s economic development. Then in 1685, Louis revoked the Edict of Nantes, prompting between 200,000 and 300,000 Huguenots to leave France, many of them skilled craftsmen, intellectuals, army officers whom France could not afford to lose.

Eighteenth century France

Louis XV (reigned 1715-1774) sought escape in pleasure, discredited the monarchy, and was so unpopular that his body was buried secretly. His grandson, Louis XVI (reigned 1774-1792), was weak-willed, and his young queen, Marie Antoinette, frivolous and extravagant. In the eighteenth century, France was the richest and most powerful nation on the Continent. French architecture, design, fashion, and taste were imitated through the Western world, while French political and social ideas influenced Europe and America. It was a period of great economic growth. The country's industrial revolution began in that century, when the France was the leading industrial power in the world.

But the income of urban laborers and artisans, was eroded by inflation, and peasants were heavily burdened by taxes, tithes, and feudal obligations. The tax system, which exempted the lands of the nobility and the clergy, deprived the government of a significant source of revenue, and put an unfair burden on the peasantry and the bourgeoisie.

Successive ministries tried to establish a balanced taxation system of all wealth, but were blocked by privileged groups and by the lack of support from the King. The nobility in the parliaments led opposition to royal initiatives, posing as defenders of public liberties, but were advocating a return to government by the aristocracy. The philosophes, French writers on political, social, and economic problems, led intellectual opposition, arguing that all people had certain natural rights-—life, liberty, and property—-and that governments existed to guarantee these rights.

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), were costly. By 1763, France lost almost all of its vast colonial empire in America and in India. The Vente de la Louisiane Louisiana Purchase vastly enlarged the United States of America. In 1778, the French became involved in the American War of Independence, against Britain, hoping to recover lost colonies, but only managed to increased an already heavy national debt.

The French Revolution

The French Revolution (1789–1799) was a period of political and social upheaval in the political history of France and Europe as a whole, during which the French governmental structure, previously an absolute monarchy with feudal privileges for the aristocracy and Catholic clergy, underwent radical change to forms based on Enlightenment principles of republic, citizenship, and inalienable rights. These changes were accompanied by violent turmoil, including executions and repression during the Reign of Terror, and warfare involving every other major European power.

On June 17, 1789, the 1200 deputies elected to the Estates-General declared themselves the National Assembly of France. When the government tried to disperse the assembly by force, the people of Paris stormed of the Bastille, a symbol of the hated Ancien Regime, on July 14, 1789, and forced the king to accept the National Assembly. A peasant revolt spread across the country. The alarmed assembly, in an all-night session, on August 4-5, abolished all feudal dues and privileges, hereditary nobility, and titles.

From 1789 to 1791, the National Assembly confiscated the property of the Church, issued paper money, established a new provincial administrative and judicial system, centered on locally elected officials and judges, and adopted a constitution in 1791 which created a parliamentary government with an hereditary monarch and an assembly indirectly elected by tax-paying citizens.

Louis XVI was an unwilling constitutional monarch, and militants were determined to establish a French republic. An uprising overthrew the monarchy on August 10, 1792, a new constituent assembly was elected by universal male suffrage, and in September 1792 it established the First French Republic. The assembly, known as the National Convention, used the Committee of Public Safety to deal with the crisis created by defeats by Austria and Prussia, rebellion, food shortages, and disarray among government officials. The committee instituted the Reign of Terror to eliminate enemies and to gain control. King Louis XVIwas tried and executed in January 1793 and Queen Marie Antoinette in October.

Meanwhile, Sardinia, Austria, and Britain were still at war with France. In 1795, the National Convention adopted a constitution outlining a republic with executive power vested in a five-man Directory and legislative power divided between two houses, indirectly elected ensuring control by citizens with substantial property. The Directory governed France through four years. Stability was threatened by Royalists eager to restore the monarchy and by Jacobins wanting a democratic republic. A number of men in key positions backed the young general Napoleon Bonaparte who in November 1799, overthrew the Directory and established the Consulate.

Napoleon and the Empire

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) shaped a new constitution which placed all essential powers in the office he assumed, that of First Consul. Once in power, he forced Austria to make peace in 1801, and ended hostilities with Britain with the Treaty of Amiens (1802). He re-established the Roman Catholic Church as a state church. The Napoleonic code confirmed the abolition of feudal privileges, equality before the law, freedom of conscience, the individual’s free choice of occupation, and guarantees against arbitrary arrest and detention—all goals of the French Revolution. Napoleon placed control of the 83 administrative units set up by the National Assembly under a prefect appointed by the Ministry of the Interior. He established the Bank of France, created the franc as a new unit of currency, and organized the Imperial University to direct and control the nation’s teachers.

In 1804, Napoleon established the French Empire and crowned himself emperor, and in 1805, he went to war, defeating Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Britain controlled the seas after destroying the French fleet in 1805 off Cape Trafalgar, so Napoleon closed Europe to British trade. But his army was destroyed in Russia in 1812, and he was driven from Germany in 1813. He abdicated in April 1814 and surrendered to the allies. The allied rulers were convinced that restoration of the Bourbon monarchy would establish a peaceful France. In May the younger brother of the executed Louis XVI entered Paris as King Louis XVIII.

The new government was unpopular; the allies at the Congress of Vienna fell out as they tried to redraw the map of Europe. In March 1815, Napoleon escaped from exile on the island of Elba. The army backed him, Louis fled, and Napoleon re-established the empire, to be defeated on June 18, 1815, at Waterloo. Napoleon surrendered, and was imprisoned on the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821. Louis returned, and the Bourbon monarchy was restored.

Constitutional monarchy

The French monarchy was re-established, but with new constitutional limitations, the allied rulers imposed a military occupation of two-thirds of the country for five years, and required heavy indemnity payments. In a wave of revenge against Bonapartists and Republicans, scores were killed and hundreds wounded. The parliamentary elections in 1815 returned an ultra-Royalist chamber, which Louis dissolved. New elections brought moderate Royalists, economic productivity recovered, and the foreign occupation ended in 1818. The heir to the throne was assassinated in 1820, which led to the accession of ultra-Royalist Charles X (1757-1836) in 1824, who provided a stable government, enabling industry and commerce to thrive.

Revolutions of 1830 and 1848

An economic slowdown led to a political crisis, which in 1829 prompted Charles to dissolve the chamber. New elections confirmed an anti-Royalist majority, which Charles chose to defy. On July 26, 1830, he ordered new elections, with fewer voters, and press restrictions. Protests led to three days of street fighting. Charles abdicated and Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans (1773-1850), was called to the throne as the last king of France. The king’s power to issue ordinances was eliminated, and the franchise was extended. Riots by disappointed Republicans and poor urban workers disrupted the regime of Louis Philippe, known as the July Monarchy, but it became firmly established by 1835.

Industrial production accelerated rapidly after 1840, and the migration from the country to urban areas mounted. From 1833, every commune in France was required to maintain a primary school for boys, free to those who could not afford to pay. But Louis Philippe resisted pressure to extend of the suffrage, and an economic depression in 1846 and 1847 undermined the regime’s support. In February 1848, a clash between troops and demonstrators turned into a revolution. Louis Philippe abdicated on February 24, and a group of Republican leaders proclaimed the Second French Republic.

Second Republic and Second Empire

Struggle between moderate and radical Republicans marked the first four months of the Second Republic, followed by three days of bloody street fighting in Paris known as the June Days. A constitution, adopted in November 1848, set up a presidential republic with a single assembly, based on universal male suffrage. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (1808-1873), nephew of the former Emperor, won the presidency, while Monarchists hostile to the Republic dominated the assembly, making effective government difficult. Louis Napoleon seized power on December 2, 1851. One year later he restored the empire, and in 1852 took the imperial title of Napoleon III of France. The era saw great industrialization, urbanization (including the massive rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann), and economic growth, but Napoleon III's foreign policies was not successful. Louis-Napoléon was unseated following defeat in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and his regime was replaced by the Third Republic.

The Third Republic and The Dreyfus Affair

In March, 1871, radical Republicans in Paris rebelled and set up the Commune of Paris, controlling the capital for two months until government troops recaptured the city. In 1875, Republicans won approval for a republican constitution. The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal which divided France from the 1890s to the early 1900s. It involved the wrongful conviction for treason of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a promising young artillery officer in the French Army. Dreyfus was a Jew who had been born in the German-speaking Alsace that became part of the German Empire in 1871. The political and judicial scandal that followed lasted until Alfred Dreyfus was fully vindicated, after which he served in World War I as a lieutenant-colonel and was raised to the rank of Officer of the Legion of Honor.

World War I

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was murdered, triggering a chain of events causing the First World War. On August 3, the German Empire declared war to France and violated Belgium's neutrality, causing both France and Great-Britain to enter the war. Much of the war was fought on French territory. Though ultimately a victor, France suffered enormous human and material losses that weakened it for decades. About 1,394,000 men, 25 percent of all French men between the ages of 18 and 30, had been killed, and the north-eastern departments had been devastated. Peace terms were found in the Treaty of Versailles, largely negotiated by Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) for French matters. Germany was required to take full responsibility for the war and to pay war reparations; and the German industrial Saarland, a coal and steel region, was occupied by France. The German African colonies were partitioned between France and Britain such as Cameroons, Alsace-Lorraine was returned to France.

After the war, the value of the franc dropped from 20 cents to 2 cents, hitting the bourgeoisie, the main supporters of the Republic, who relied on their savings. The Great Depression ended a brief interlude of prosperity and calm, followed by the resurgence after 1933, of a militant, aggressive Germany. In 1934, the Radical-Socialist, Socialist, and Communist parties joined in the Popular Front, winning control of the Chamber of Deputies in 1936. Léon Blum's Popular Front government dissolved Fascist organizations, establish paid holidays, a 40-hour week, and compulsory collective bargaining, before it fell apart in 1938 amid party quarrels and the threat of war.

World War II

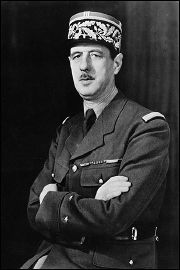

On May 10, 1940, German forces invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, and pushed through to the Channel coast, cutting off 45 French and British divisions, which were evacuated from Dunkirk to Britain. On June 22, the aged Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856-1951) surrendered to Germany. About two-thirds of French territory was occupied by German forces at French expense, while the Germans established a puppet regime under Pétain, known as Vichy France, which collaborated with Nazi Germany. Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), a French general, built a small armed force and a shadow government in England, and was accepted by the Resistance movements inside France as the leader of a united opposition to Vichy and the Germans. On August 25, 1944, the Americans liberated Paris. De Gaulle organized a national provisional government, which he dominated for the next 15 months, until he stepped down in January 1946.

France during the Cold War

After a short period of provisional government initially led by General Charles de Gaulle, a new constitution (October 13, 1946) established the Fourth Republic under a parliamentary form of government controlled by a series of coalitions. During the following 16 years the French Colonial Empire would disintegrate. In Indochina the French government was facing the Viet Minh, socialist rebels, and lost its Indochinese colonies during the First Indochina War after the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. Vietnam was divided in two states while Cambodge and Laos were made independent. The May 1958 seizure of power in Algiers by French army units and French settlers opposed to concessions in the face of Arab nationalist insurrection led to the fall of the French government and a presidential invitation to de Gaulle to form an emergency government to forestall the threat of civil war. In May 1968, students revolted, with a variety of demands including educational, labor and governmental reforms, sexual and artistic freedom, and the end of the Vietnam War. The student protest movement quickly joined with labor and mass strikes erupted.

The new world order

While France continues to revere its rich history and independence, French leaders increasingly tie the future of France to the continued development of the European Union. Jacques Chirac assumed office as president on May 17, 1995, after a campaign focused on the need to combat France's high unemployment rate. The French have stood among the strongest supporters of NATO and EU policy in the Balkans, in order to prevent genocide in Yugoslavia, it contributed to the toppling of the Taliban-regime in Afghanistan in 2002, but it strongly rejected the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Jacques Chirac was re-elected in 2002, mainly because his socialist rival Lionel Jospin was defeated by the extreme right wing candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen. At the end of his second term he chose not to run again at the age of 74. His former protege, cabinet minster and rival Nicolas Sarkozy was elected as his successor and took office on May 16, 2007. The problem of high unemployment was yet to be resolved.

Government and politics

Constitutional structure

The French Republic is a unitary semi-presidential republic with strong democratic traditions. The constitution of the Fifth Republic was approved by referendum on September 28, 1958. It greatly strengthened the authority of the executive in relation to parliament.

The president is the chief of state and is elected by popular vote for a five-year term (formerly seven years). An election was held in April and May of 2007. The prime minister is nominated by a national assembly majority and appointed by the president. A council of ministers appointed by the president at the suggestion of the prime minister.

The French parliament is a bicameral legislature comprising a national assembly (Assemblée Nationale) and a senate. The 577 national assembly deputies (555 for metropolitan France, 15 for overseas departments, and seven for dependencies) are elected by popular vote under a single-member majority system to serve five-year terms. The assembly has the power to dismiss the cabinet, and thus the majority in the Assembly determines the choice of government.

The 331 senators (305 for metropolitan France, nine for overseas departments, five for dependencies, and 12 for French nationals abroad) are indirectly elected by an electoral college to serve nine-year terms, with one third elected every three years. The Senate's legislative powers are limited; in the event of disagreement between the two chambers, the National Assembly has the final say, except for constitutional laws and lois organiques (laws that are directly provided for by the constitution) in some cases. The government has a strong influence in shaping the agenda of Parliament.

Suffrage is universal for those aged 18 and over. French politics are characterized by two politically opposed groupings: one left-wing, centered around the French Socialist Party, and the other right-wing, centered previously around the Rally for the Republic(RPR)]] and now its successor the Union for a Popular Movement. The executive branch was composed mostly of the UPM in 2007.

The judiciary consists of Supreme Court of Appeals (Cour de Cassation), the judges of which are appointed by the president from nominations of the High Council of the Judiciary, a Constitutional Council with three members appointed by the president, three appointed by the president of the National Assembly, and three appointed by the president of the Senate, and the Council of State.

Law

France uses a civil legal system, which is law arising from written statutes; judges are not to make law, but merely to interpret it (though the amount of judicial interpretation in certain areas makes it equivalent to case law). Basic principles of the rule of law were laid in the Napoleonic Code. In agreement with the principles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen law should only prohibit actions detrimental to society. French law is divided into private law, which includes civil law and criminal law, and public law, which includes administrative law and constitutional law. France does not recognize religious law, nor does it recognize religious beliefs or morality as a motivation for the enactment of prohibitions. As a consequence, France has long had neither blasphemy laws nor sodomy laws (the latter being abolished in 1791). However "offenses against public decency" or breach of the peace have been used to repress public expressions of homosexuality or street prostitution.

Foreign relations

France is a member of the United Nations and serves as one of the permanent members of the U.N. Security Council with veto rights. It is also a member of the World Trade Organization, the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), the Indian Ocean Commission (COI). It is an associate member of the Association of Caribbean States (ACS) and a leading member of the International Francophone Organisation (OIF) of 51 fully or partly French-speaking countries. It hosts the headquarters of the OECD, UNESCO, Interpol, Alliance Base and the International Bureau for Weights and Measures.

French foreign policy has been largely shaped by membership of the European Union, of which it was a founding member. In the 1960s, France sought to exclude the British from the organization, seeking to build its own standing in continental Europe. Since the 1990s, France has developed close ties with reunified Germany to become the most influential driving force of the EU, but consequently rivaling the U.K. and limiting the influence of newly-inducted East European nations. France is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, but under President de Gaulle, it excluded itself from the joint military command to avoid the supposed domination of its foreign and security policies by U.S. political and military influence. In the early 1990s, the country drew considerable criticism from other nations for its atmospheric nuclear tests in Polynesia. France vigorously opposed the 2003 invasion of Iraq, straining bilateral relations with the U.S. and the U.K. France retains strong political and economic influence in its former African colonies (Francophone) and has supplied economic aid and troops for peace-keeping missions in the Cote d'Ivoire and Chad.

Military

The French armed forces comprises an army, navy, air force, and French Gendarmerie, a military force which acts as a National Rural Police and as a Military police for the entire French military. Conscription was suspended in 2001. The total number of military personnel is approximately 359,000. France spends 2.6 percent of its GDP on defense, slightly more than the United Kingdom (2.4 percent), and is the highest in the European Union. About 10 percent of France's defense budget goes towards its nuclear weapons. A significant part of French military equipment is made in France, including the Rafale fighter, the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier, the Exocet missile, and the Leclerc tank.

The French nuclear force consisted, in 2007, of four submarines equipped with M45 ballistic missiles. The French dissuasion force uses the Mirage 2000N; it is a variant of the Mirage 2000 and thus is designed to deliver nuclear strikes. Other nuclear devices like the Plateau d'Albion's Intercontinental ballistic missiles and the short range Hadès missiles have been disarmed. With 350 nuclear heads stockpiled France is the world's third largest nuclear power.

Administrative divisions

France is divided into 26 administrative regions. Twenty two are in metropolitan France (21 are on the continental part of metropolitan France; one is the territorial collectivity of Corsica), and four are overseas regions. The regions are further subdivided into 100 departments which are numbered (mainly alphabetically). This number is used in postal codes and vehicle number plates amongst others. The 100 departments are subdivided into 341 arrondissements which are, in turn, subdivided into 4032 cantons. These cantons are then divided into 36,680 communes, which are municipalities with an elected municipal council. Three communes, Paris, Lyon and Marseille are also subdivided into 45 municipal arrondissements.

The regions, departments and communes are all known as territorial collectivities, meaning they possess local assemblies as well as an executive. Arrondissements and cantons are merely administrative divisions.

The French Republic also has six overseas collectivities, one sui generis collectivity (New Caledonia), and one overseas territory. Overseas collectivities and territories form part of the French Republic, but do not form part of the European Union or its fiscal area. The Pacific territories continue to use the Pacific franc whose value is linked to that of the euro. In contrast, the four overseas regions used the French franc and now use the euro.

France also maintains control over a number of small non-permanently inhabited islands in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean: Bassas da India, Clipperton Island, Europa Island, Glorioso Islands, Juan de Nova Island, and Tromelin Island. Overseas departments have the same political status as metropolitan departments. They include Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, and Réunion, all since 1946.

Marianne

Marianne is a symbol of the French Republic. She is an allegorical figure of liberty and the Republic and first appeared at the time of the French Revolution. The earliest representations of Marianne are of a woman wearing a Phrygian cap. The origins of the name Marianne are unknown, but Marie-Anne was a common first name in the eighteenth century. Anti-revolutionaries of the time derisively called her La Gueuse (the Commoner). It is believed that revolutionaries from the South of France adopted the Phrygian cap as it symbolized liberty, having been worn by freed slaves in both Greece and Rome. Mediterranean seamen and convicts manning the galleys also wore a similar type of cap.

Economy

After the Second World War, France embarked on an ambitious program of modernization, known as dirigisme. Mostly implemented by socialist governments, it involved the state control of industry, such as transportation, energy and telecommunications infrastructures. However, dirigisme came to be highly contested after 1981 when newly elected socialist president François Mitterrand called for increased governmental control in the economy, nationalizing many industries and private banks. By 1983, with the initial bad economic results the government decided to renounce dirigisme and start the era of rigueur ("rigour") or "corporatization."

France, in 2007, was in the midst of transition from a well-to-do modern economy that has featured extensive government ownership and intervention to one that relies more on market mechanisms. The government has partially or fully privatized many large companies, banks, and insurers, and has ceded stakes in such leading firms as Air France, France Telecom, Renault, and Thales. It maintains a strong presence in some sectors, particularly power, public transport, and defense industries. The telecommunications sector is gradually being opened to competition.

France's leaders remained committed to a capitalism in which tax policies and social spending reduce income disparity. The government in 2006 focused on introducing measures that attempt to boost employment through increased labor market flexibility; however, the population has remained opposed to labor reforms.

The tax burden remained one of the highest in Europe (nearly 50 percent of GDP in 2005). The lingering economic slowdown and inflexible budget items probably pushed the budget deficit above the eurozone's three percent-of-GDP limit in 2006; unemployment hovers near nine percent. With at least 75 million foreign tourists per year, France is the most visited country in the world and maintains the third largest income in the world from tourism.

Legislation passed in 1998 shortened the legal workweek from 39 to 35 hours. A key objective was to encourage job creation, for which significant new subsidies were to be made available.

Membership in France's laboor unions accounted for less than 10 percent of the private sector workforce and is concentrated in the education, manufacturing, transportation, and heavy industry sectors. Most unions are affiliated with one of the competing national federations, the largest and most powerful of which are the CGT, FO, and CFDT. French unions are fairly weak, and strikes are uncommon in most of the economy. Nonetheless, unions are powerful in some parts of the public sector, particularly public transportation (SNCF national railways, RATP Paris transit authority and air traffic control), where strikes attract the attention of the national and foreign press.

A member of the G8 group of leading industrialized countries, it is ranked as the sixth largest economy in the world in 2005, behind the United States, Japan, Germany, The People's Republic of China and the United Kingdom. France joined 11 other EU members to launch the Euro on January 1, 1999, with euro coins and banknotes replacing the French franc (₣) in early 2002.

In the 2005 edition of OECD in Figures, the OECD noted that France led the G7 countries in terms of productivity (measured as GDP per hour worked). In 2004, the GDP per hour worked in France was $47.7, ranking France above the United States ($46.3), Germany ($42.1), the United Kingdom ($39.6), or Japan ($32.5). But France's GDP per capita is significantly lower than the US GDP per capita. The reason for this is that a much smaller percentage of the French population is working compared to the US, which lowers the GDP per capita of France, despite its higher productivity. In fact, France has one of the lowest percentages of its population aged 15-64 years at work among the OECD countries. In 2004, 68.8 percent of the French population aged 15-64 years was in employment, compared to 80 percent in Japan, 78.9 percent in the UK, 77.2 percent in the US, and 71 percent in Germany.

France has an important aerospace industry led by the European consortium Airbus, and is the only European power (excluding Russia) to have its own national spaceport, (Centre Spatial Guyanais). France is also the most energy independent Western country due to heavy investment in nuclear power, which also makes France the smallest producer of carbon dioxide among the seven most industrialized countries in the world. As a result of large investments in nuclear technology, most of the electricity produced in the country is generated by nuclear power plants (78.1 percent in 2006, up from only eight percent in 1973.

Large tracts of fertile land, the application of modern technology, and EU subsidies have combined to make France the leading agricultural producer and exporter in Europe. Wheat, poultry, dairy, beef, and pork, as well as an internationally recognized foodstuff and wine industry are primary French agricultural exports. EU agriculture subsidies to France total almost $14-billion.

Exports totaled $483.1-billion in 2006. Export commodities included machinery and transportation equipment, aircraft, plastics, chemicals, pharmaceutical products, iron and steel, and beverages. Export partners included Germany 15.6 percent, Spain 9.6 percent, Italy 8.9 percent, the UK 8.2 percent, Belgium 7.2 percent, the US 6.7 percent, Netherlands 4 percent.

Imports totaled $520.8-billion in 2006. Import commodities included machinery and equipment, vehicles, crude oil, aircraft, plastics, and chemicals. Import partners included Germany 19 percent, Belgium 11 percent, Italy 8.3 percent, Spain 7 percent, Netherlands 6.7 percent, UK 6.5 percent, US 4.6 percent.

The GDP per_capita was $35,404 in 2006, a rank of 18 out of 194 countries. The unemployment rate was 8.7 percent in 2006, and 6.2 percent of the population existed below the poverty line in 2004.

Demography

Population

With a total population of just over 67 million people, with 65 million in metropolitan France, France is the 20th most populous country in the world and the third-most populous in Europe. France is also second most populous country in the European Union after Germany.

France is an outlier among developed countries in general, and European countries in particular, in having a fairly high rate of natural population growth. Immigrants are also major contributors to this trend.

Ethnicity

Since the beginning of the Third Republic (1871-1940), the state has not categorized people according to their alleged ethnic origins, to prevent discrimination. The French Constitution holds that "French" is a nationality, and not a specific ethnicity. France is an ethnically diverse nation, including people of Celtic, Latin, Teutonic, Slavic, North African, Indochinese ancestry, as well as Basque minorities. Conflict between the government and regional groups including Corsicans, Bretons, and Basques escalated toward the end of the twentieth century, with a heightened push for political autonomy.

Religion

France is a secular country where freedom of thought and of religion are preserved, in virtue of the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The Republic is based on the principle of laïcité, that is of freedom of religion (including agnosticism and atheism) enforced by the 1880s Jules Ferry laws and the 1905 French law on the separation of church and state. Not until 1993 did France outlaw polygamy. The French government is legally prohibited from recognizing any religion. Instead, it merely recognizes religious organizations, according to formal legal criteria that do not address religious doctrine. Conversely, religious organizations are expected to refrain from intervening in policy-making. Tensions occasionally erupt into violence about alleged discrimination against minorities, especially against Muslims.

Roman Catholicism, the religion of up to 88 percent of the French people, is no longer considered a state religion, as it was before the 1789 Revolution and throughout the various, non-republican regimes of the nineteenth century (the Restauration, the July Monarchy and the Second Empire).

According to a January 2007 poll by the Catholic World News: 51 percent identified as being Catholics, 31 percent identified as being agnostics or atheists. (Another poll concluded that 27 percent identified as being atheists), ten percent identified as being from "other religions" or being without opinion, 4 percent identified as Muslim, 3 percent identified as Protestant, 1 percent identified as Jewish.

The current Jewish community in France numbers around 600,000 according to the World Jewish Congress and is largest in Europe. Estimates of the number of Muslims in France vary widely. According to the 1999 French census returns, there were only 3.7 million people of "possible Muslim faith" in France (6.3 percent of the total population).

There are an estimated 200,000 to 1 million illegal immigrants in France.

Language

French is a Romance language originally spoken in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Switzerland, and today by about 300 million people around the world as either a native or a second language. French is a descendant of the Latin of the Roman Empire, as are languages such as Spanish, Italian, Catalan, Romanian, and Portuguese. Its development was also influenced by the native Celtic languages of Roman Gaul and by the Germanic language of the post-Roman Frankish invaders. It is an official language in 29 countries, most of which form what is called in French La Francophonie, (Frankophone) the community of French-speaking nations, and is an official language of all United Nations agencies. France has two linguistic regions: that of the langue d'oeil to the north and that of the langue d'oc to the south.

According to Article 2 of the Constitution, French is the sole official language of France since 1992. This makes France the only Western European nation (excluding microstates) to have only one officially recognized language. However, 77 regional languages are also spoken, in metropolitan France as well as in the overseas departments and territories. These include Breton, Catalan, Corsican, Basque, Alsatian, and Flemish. The French government and state school system discouraged the use of any of these languages, but they are now taught to varying degrees at some schools. Other languages, such as Portuguese, Italian, Maghrebi Arabic and several Berber languages are spoken by immigrants.

L'Académie française, or the French Academy, is the pre-eminent French learned body on matters pertaining to the French language. The Académie was officially established in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister to King Louis XIII. It was suppressed in 1793 during the French Revolution, and was restored in 1803 by Napoleon Bonaparte. It is the oldest of the five académies of the Institut de France. The Académie consists of 40 members, known as immortals (immortals). New members are elected by the members of the Académie. Académicians hold office for life, but they may be removed for misconduct. The Academy publishes an official dictionary.

Men and women

Traditionally, in peasant households, women carried out the domestic tasks of housekeeping, food preparation, and child care. With industrialization, women worked outside the home as washerwomen, factory workers, and domestics. By the end of the twentieth century, almost half of all workers were female and the dual-career family was normal. However, women continued to face lower wages than men for comparable work and more difficult career paths. Women did not gain the right to vote until 1944, and it was only in the 1960s that wives gained the right to open bank accounts or work without the husband's permission.

Marriage and the family

The marriage rate was declining in 2007, the average age of marriage for men was 29, and that for women 27. Most marriages involve partners from the same area, and mostly from the same religion. The Socialist government of the 1980s, under a policy called "family reunification" opened the way for polygamy, by allowing immigrants to bring their extended families into France legally. Polygamy was outlawed in 1993, but as many as 150,000 to 400,000 families, many from Mali, remain in polygamous or "semi-polygamous" family situations. Generous benefits from the government in some cases may be financially supporting 20 or more members of a single family, when a husband has multiple wives and dozens of children. In recent years, one in three marriages ends in divorce. All marriages have a civil ceremony in the town hall, and many are followed by a religious ceremony. Payment for the weddings is divided equally between both families. Cohabitation of unmarried couples has increased. A law, passed in 1999, set up an intermediate union between marriage and cohabitation, including homosexual couples, which is easier to dissolve than a marriage.

The basic domestic unit is called le ménage, which includes all persons living in the same dwelling, and who are not necessarily related. In 1997, most households consisted of couples with (35 percent) or without (28 percent) children. Single women made up 18 percent of all households, and 12 percent of single men. The nuclear family was most prevalent in southern France, and is where a young couple is established in their own household by both sets of parents. The patriarchal family prevailed in rural areas of central France, where siblings stayed at home, with their spouses, and owned property jointly, as did the stem family, where the eldest son would remain in the family home, while other siblings had to seek their fortunes elsewhere. That pattern persists in some country areas, although primogeniture has been illegal since 1804. The family continues to play a key role in transmitting cultural values.

Education

The French educational system is highly centralized, and is divided into three different stages: primary, secondary, and higher education. Primary and secondary education is predominantly public (private schools also exist, in particular a strong nationwide network of primary and secondary Catholic schools), while higher education has both public and private elements.

While the French trace the development of their educational system to Charlemagne, the modern era of French education begins at the end of the nineteenth century. Jules Ferry, a lawyer holding the office of Minister of Public Instruction in the 1880s, is widely credited for creating the modern Republican school by requiring all children under the age of 15—boys and girls—to attend. He also made public instruction free of charge and secular.

The teachers in public primary and secondary schools are all state civil servants, making the ministère the largest employer in the country. Professors and researchers in France's universities are also employed by the state. At the primary and secondary levels, the curriculum is the same for all French students in any given grade, which includes public, semi-public and subsidized institutions. However, there exist specialized sections and a variety of options that students can choose.

Higher education in France is divided into grandes écoles and universities. Grandes écoles are considered more prestigious than universities. For example in France most prestigious engineering Grandes École, École polytechnique have about 12,000 applicants for 400 places. A striking trait of French higher education, in contrast with other countries, is the small size and multiplicity of establishments, each specialized in a more or less broad spectrum of disciplines.

In 2003, 99 percent of the population over the age of 15 could read and write.

Class

Historically, France was divided among the nobility, the bourgeoisie, the peasants, and the urban proletariat, providing the basis for much of Karl Marx's nineteenth century analysis of class struggle. The modern social structure, which started in the late 1950s, is based on three distinct classes. There are the high level politicians, the wealthy families and the also powerful business owners. The middle class group comprises two different types of white-collar jobs—senior executives, and those in high-income, stable, professional jobs. The lower class comprises blue-collar workers in food-service jobs or retail. Unemployment and the low living standards are common in this group. The number of blue-collar jobs has decreased while the civil service section has steadily increased. Children tend to remain in the occupational class of their parents, a situation attributed to the school system. Symbols of a higher class position include knowing about fine art and the newest trends, appreciating and being able to afford fine wines, and dressing with understatement. Wealth and family connections and lifestyle determine social position.

Culture

Architecture

Although there is no architecture named French Architecture, Gothic Architecture's old name was French Architecture (or Opus Francigenum). Northern France is the home of some of the most important Gothic cathedrals and basilicas, the first of these being the Saint Denis Basilica (used as the royal necropolis); other majestic and important French Gothic cathedrals are Notre-Dame de Chartres and Notre-Dame d'Amiens. The kings were crowned in another important Gothic church: Notre-Dame de Reims, and French popes lived in the Gothic Palais des Papes in Avignon.

During the Middle Ages, fortified cities were common, as were fortified castles built by feudal nobles to mark their power. Some important French castles that survived are Chinon Castle, Château d'Angers, the massive Château de Vincennes, and the so-called Cathar castles. Romanesque architecture which used Mooresque architecture prevailed before the rise of the Gothic style. Romanesque churches in France include the Saint Sernin Basilica in Toulouse and the remains of the Cluniac Abbey (largely destroyed during the Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars).

The end of the Hundred Years' War marked the French Renaissance. Numerous Italian-inspired residential palaces were built, mainly in the Loire Valley, including the Château de Chambord, the Château de Chenonceau, or the Château d'Amboise. Following the Renaissance and the end of the Middle Ages, Baroque Architecture replaced Gothic. The Palace of Versailles has many baroque features. Jules Hardouin Mansart can be said to be the most influential French architect of the baroque style, with his very famous baroque dome of Les Invalides.

Neoclassicism was introduced before the revolution with such buildings as the Parisian Pantheon and the Capitole de Toulouse. Built during the French Empire the Arc de Triomphe and Sainte Marie-Madeleine represent this trend the best.

Under Napoleon III (1808-1873) a new wave of architecture appeared, including the neo-baroque Palais Garnier. The urban planing of the time was organized and rigorous, such as Baron Haussmann's renovation of Paris. In the late nineteenth century Gustave Eiffel designed many bridges (like the Garabit viaduct) and remains one of the most influential bridge designer of his time, although he is best remembered for the Eiffel Tower.

In the twentieth century the Swiss Architect Le Corbusier designed several buildings in France. More recently French architects have combined both modern and old architectural styles. The Louvre Pyramid of I.M. Pei is a good example of modern architecture added to an older building. France's largest financial district La Defense has a significant number of skyscrapers.

Art

The first paintings of France are those that are from prehistoric times, painted in the caves of Lascaux well over 10,000 years ago. The arts flourished already 1200 years ago, at the time of Charlemagne, as can be seen in many hand made and hand illustrated books of that time. Classic painters of seventeenth century France are Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain. During the eighteenth century, the Rococo style emerged as a frivolous continuation of the Baroque style. The most famous painters of the era were Antoine Watteau, François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard. At the end of the century, Jacques-Louis David was the most influential painter of the Neoclassicism.

Géricault and Delacroix were the most important painters of the Romanticism. The realistic movement was led by Courbet and Honoré Daumier. Impressionism was developed in France by artists such as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Camille Pissarro. At the turn of the century, France had become the center of innovative art. The Spaniard Pablo Picasso came to France, like many other foreign artists, to deploy his talents there for decades to come. Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin and Cézanne were painting then. Cubism is an avant-garde movement born in Paris at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The Louvre in Paris is one of the most famous and the largest art museums in the world, created by the new revolutionary regime in 1793 in the former royal palace. It holds a vast amount of art of French and other artists, including the Mona Lisa, by Leonardo da Vinci, and classical Greek Venus de Milo and ancient works of culture and art from Egypt and the Middle East.

Cinema

Auguste and Louis Lumière invented the cinématographe, and their screening of L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de la Ciotat in Paris in 1895 is marked by many historians as the official birth of cinematography. During the next few years, France's Georges Méliès invented many common cinematic techniques, and made the first ever science fiction film A Trip to the Moon (1902). Alice Guy Blaché made her first film in 1896, La Fée aux Choux, and was head of production at Gaumont 1897-1906, where she made in total about 400 films. Her career continued in the United States.

During the period between World War I and World War II, Jacques Feyder became one of the founders of poetic realism in French cinema. He was also a dominating character within French Impressionist Cinema. The French film industry suffered from a lack of investment after the First World War, creating an opportunity for the US film industry to enter the European cinema market with their own films, which could be sold cheaper than the European productions. A quota system was introduced to protect French cinema.

In 1937, Jean Renoir, the son of famous painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, directed what many see as his first masterpiece, La Grande Illusion (The Grand Illusion). In 1939 Renoir directed La Règle du Jeu (The Rules of the Game).

Modern film theory was born in the critical magazine Cahiers du cinéma, founded by André Bazin, in which critics and lovers of film would discuss film and why it worked. Cahiers critics such as Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol, went on to make films themselves, creating what was to become known as the French New Wave. Some of the first movies of this new genre was Godard's Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960), starring Jean-Paul Belmondo and - the leading movie - Truffaut's The 400 Blows (Les Quatre Cent Coups, 1959) starring Jean-Pierre Léaud.

Cuisine

see also French Cuisine