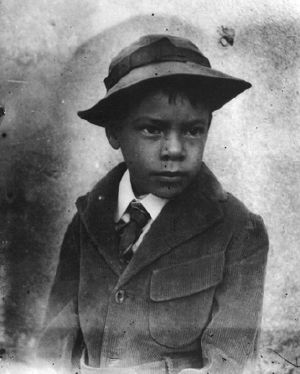

Francisco (Pancho) Villa

| Doroteo Arango Arámbula | |

|---|---|

| June 5, 1878-July 23, 1923 | |

Villa at Battle of Torreón | |

| Nickname | Pancho Villa El Centauro del Norte (The Centaur of the North) |

| Place of birth | |

| Place of death | |

| Allegiance | Mexico (antireeleccionista revolutionary forces) |

| Rank | General |

| Commands held | División del Norte |

Doroteo Arango Arámbula (June 5, 1878 – July 23, 1923), better known as Francisco or "Pancho" Villa, was a Mexican Revolutionary general. As commander of the División del Norte (Division of the North), he was the veritable caudillo of the Northern Mexican state of Chihuahua, which, due to its size, mineral wealth, and proximity to the United States, made him a major player in Revolutionary military and politics. His charisma and effectiveness gave him great popularity, particularly in the North, and he was provisional Governor of Chihuahua in 1913 and 1914. While his violence and ambition prevented his from being accepted into the "pantheon" of national heroes until some twenty years after his death, today his memory is honored by many Mexicans, and numerous streets and neighborhoods in Mexico are named for him. In 1916, he raided Columbus, New Mexico. This act provoked the unsuccessful Punitive Expedition commanded by General John J. Pershing, which failed to capture Villa after a year in pursuit.

Villa and his supporters, known as Villistas, employed tactics such as propaganda and firing squads against his enemies, and expropriated hacienda land for distribution to peasants and soldiers. He robbed and commandeered trains, and, like the other Revolutionary generals, printed fiat money to pay for his cause. Villa's non-military revolutionary aims, unlike those of Emiliano Zapata and the Zapatista Plan de Ayala, were not clearly defined. Villa only spoke vaguely of creating communal military colonies for his troops. Despite extensive research by Mexican and foreign scholars, many of the details of Villa's life are in dispute. What is not in dispute is that the violence which Villa fomented and propagated led to decades of political instability and economic insecurity for Mexico.

Pre-revolutionary life

Little can be said with certainty of Doroteo Arango's early life. Most records claim he was born near San Juan del Río, Durango, on June 5, 1878, the son of Agustín Arango and María Micaela Arámbula. The boy was from an uneducated peasant family; the little schooling he received was provided by the local church-run village school. When his father died, Arango began to work as a sharecropper to help support his mother and four siblings. The generally accepted story states that he moved to Chihuahua at the age of 16, but promptly returned to his village after learning that an hacienda owner had tried to sexually assault his younger sister, who was only twelve years old at the time. Arango confronted the man, whose name was Agustín Negrete, and shot him dead. He then stole a horse and dashed towards the rugged Sierra Madre mountains one step ahead of the approaching police. His career as a bandit was about to begin.[1]

Pancho Villa underwent a transformation after meeting Abraham González, the political representative (and future governor of the state) in Chihuahua of Francisco Madero, who was opposing the continuing and lengthy presidency of Porfirio Díaz. González saw Villa's potential as a military ally, and helped open Villa's eyes to the political world. Villa then believed that he was fighting for the people, to break the power of the hacienda owners (hacendados in Spanish) over the poverty stricken peones and campesinos (farmers and sharecroppers). At the time, Chihuahua was dominated by hacendados and mine owners. The Terrazas clan alone controlled haciendas covering in excess of 7,000,000 acres (28,000 km²), an area larger than some countries.

On November 20, 1910, as proclaimed by Madero's Plan of San Luis Potosí, the Mexican Revolution was begun to oust the dictatorship of President Porfirio Díaz. After nearly 35 years of rule, the Mexican people were thoroughly tired of corrupt government. Díaz's political situation was untenable, and his poorly paid conscript troops were no match for the motivated antirreeleccionista (anti-reelectionist) volunteers fighting for freedom and maderismo. The antirreeleccionistas removed Díaz from office after a few months of fighting. Villa helped defeat the federal army of Díaz in favor of Madero in 1911, most famously in the first Battle of Ciudad Juárez, which was viewed by Americans sitting on the top of railroad boxcars in El Paso, Texas. Díaz left Mexico for exile and after an interim presidency, Madero became president. On May 1, 1919, Villa married Soledad Seanez Holguin, who became Villa's only legal wife until his death in 1923. Although many women have claimed to have been married to Villa, in 1946, the legislature recognized Miss Seanez Holguin as Villa's only legal wife after proving the pair had had a civil and a church wedding.

Most people at that time assumed that the new, idealistic President Madero would lead Mexico into a new era of true democracy, and Villa would fade back into obscurity. But Villa's greatest days of fame were yet to come.

Orozco's counterrevolution against Madero

A counter-rebellion led by Pascual Orozco, started against Madero, so Villa gathered his mounted cavalry troops, Los dorados, and fought along with General Victoriano Huerta to support Madero. However, Huerta viewed Villa as an ambitious competitor, and later accused Villa of stealing a horse and insubordination; then he had Villa sentenced to execution in an attempt to dispose of him. Reportedly, Villa was standing in front of a firing squad waiting to be shot when a telegram from President Madero was received commuting his sentence to imprisonment. Villa later escaped. During Villa's imprisonment, a zapatista who was in prison at the time provided the chance meeting which would help to improve his poor reading and writing skills, which would serve him well in the future during his service as provisional governor of the state of Chihuahua.

Fight against Huerta's usurpation

After crushing the Orozco rebellion, Victoriano Huerta, with the federal army he commanded, held the majority of military power in Mexico. Huerta saw an opportunity to make himself dictator and began to conspire with people such as Bernardo Reyes, Félix Díaz (nephew of Porfirio Diaz), and U.S. ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, which resulted in the La decena trágica ("Ten Tragic Days") and the assassination of President Madero.[2]

After Madero's murder, Huerta proclaimed himself as provisional president. Venustiano Carranza then proclaimed the Plan of Guadalupe to oust Huerta from office as an unconstitutional usurper. The new group of politicians and generals (which included Pablo González, Álvaro Obregón, Emiliano Zapata and Villa) who joined to support Carranza's plan, were collectively styled as the Ejército Constitucionalista de México (Constitutionalist Army of Mexico), the constitucionalista adjective added to stress the point that Huerta had not obtained power via methods prescribed by Mexico's Constitution of 1857.

Villa's hatred of Huerta became more personal and intense after March 7, 1913, when Huerta ordered the murder of Villa's political mentor, Abraham González. Villa later recovered González's remains and gave his friend a hero's funeral in Chihuahua.

Villa joined the rebellion against Huerta, crossing the Río Bravo del Norte (Rio Grande) into Ciudad Juárez with a mere 8 men, 2 pounds of coffee, 2 pounds of sugar, and 500 rounds of rifle ammunition. The new United States president Woodrow Wilson dismissed Ambassador Wilson, and began to support Carranza's cause. Villa's remarkable generalship and recruiting appeal, combined with ingenious fundraising methods to support his rebellion, would be a key factor in forcing Huerta from office a little over a year later, on July 15, 1914.

This was the time of Villa's greatest fame and success. He recruited soldiers and able subordinates (both Mexican and mercenary) such as Felipe Ángeles, Sam Dreben, and Ivor Thord-Gray, and raised money via methods such as forced assessments on hostile hacienda owners (such as William Benton, who was killed in the Benton affair), and train robberies. In one notable escapade, he held 122 bars of silver ingot from a train robbery (and a Wells Fargo employee) hostage and forced Wells Fargo to help him fence the bars for spendable cash.[3] A rapid, hard-fought series of victories at Ciudad Juárez, Tierra Blanca, Chihuahua, and Ojinaga followed. Villa then became provisional governor of the state of Chihuahua. Villa considered Tierra Blanca his most spectacular victory.[4]

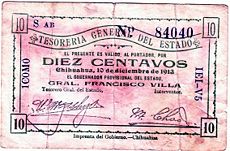

As governor of Chihuahua, Villa raised more money for a drive to the south by printing fiat currency. He decreed his paper money to be traded and accepted at par with gold Mexican pesos, under penalty of execution, then forced the wealthy to trade their gold for his paper pesos by decreeing gold to be counterfeit money. He also confiscated the gold of banks, in the case of the Banco Minero, by holding hostage a member of the bank's owning family, the wealthy and famous Terrazas clan, until the location of the bank's gold was revealed.

Villa's political stature at that time was so high that banks in El Paso, Texas, accepted his paper pesos at face value. His generalship drew enough admiration from the U.S. military that he and Álvaro Obregón were invited to Fort Bliss to meet Brigadier General John J. Pershing.

The new pile of loot was used to purchase draft animals, cavalry horses, arms, ammunition, mobile hospital facilities (railroad cars and horse ambulances staffed with Mexican and American volunteer doctors, known as Servicio sanitario), and food, and to rebuild the railroad south of Chihuahua City. The rebuilt railroad transported Villa's troops and artillery south, where he defeated Federal forces at Gómez Palacio, Torreón, and Zacatecas.[5]

Carranza tries to halt the Villa advance, the fall of Zacatecas

After Torreón, Carranza issued a puzzling order for Villa to break off action south of Torreón and instead ordered him to divert to attack Saltillo, and threatened to cut off Villa's coal supply if he did not comply. Carranza was attempting to rob Villa of his glory and keep victory for his own greedy motives. (Coal was needed for railroad locomotives to pull trains transporting soldiers and supplies, and was, therefore, necessary for any general.) This was widely seen as an attempt by Carranza to divert Villa from a direct assault on Mexico City, so as to allow Carranza's forces under Álvaro Obregón, driving in from the west via Guadalajara, to take the capital first, and Obregon and Carranza did enter Mexico City ahead of Villa. This was an expensive and disruptive diversion for the División del norte, since Villa's enlisted men were paid the then enormous sum of a peso per day, and each day of delay cost thousands of pesos. Villa did attack Saltillo as ordered, winning that battle.

Villa, disgusted by what he saw as egoism, tendered his resignation. Felipe Ángeles and Villa's officer staff argued for Villa to withdraw his resignation, defy Carranza's orders, and proceed to attack Zacatecas, a strategic mountainous city considered nearly impregnable. Zacatecas was the source of much of Mexico's silver, and, thus, a supply of funds for whomever held it. Victory in Zacatecas would mean that Huerta's chances of holding the remainder of the country would be slim. Villa accepted Ángeles' advice, canceled his resignation, and the Division del norte defeated the Federals in the Toma de Zacatecas (Taking of Zacatecas), the single bloodiest battle of the Revolution, with the military forces counting approximately 7,000 dead and 5,000 wounded, and unknown numbers of civilian casualties. (A memorial to and museum of the Toma de Zacatecas is on the Cerro de la Bufa, one of the key defense points in the battle of Zacatecas. Tourists use a teleférico (aerial tramway) to reach it, due to the steep approaches. From the top, tourists may appreciate the difficulties Villa's troops had trying to dislodge Federal troops from the peak. The loss of Zacatecas in June 1914, broke the back of the Huerta regime, and Huerta left for exile on July 14, 1914.

This was the beginning of the split between Villa, the champion of the poor and the rich, cynical constitutionalistas of Carranza. Carranza's egoismo (selfishness) would eventually become self-destructive, alienating most of the people he needed to hold power, and doom him as well.

Revolt against Carranza and Obregón

Villa was forced out of Mexico City in 1915, following a number of incidents between himself, his troops and the citizens of the city, and the humiliation of President Eulalio Gutiérrez. The return of Carranza and the Constitutionalists to Mexico City from Veracruz followed. Villa then rebelled against Carranza and Carranza's chief general, Álvaro Obregón. Villa and Zapata styled themselves as convencionistas, supporters of the Convention of Aguascalientes.

Unfortunately, Villa's talent for generalship began to fail him, in 1915. When Villa faced General Obregón in the First Battle of Celaya on April 15, repeated charges of Villa's vaunted cavalry proved to be no match for Obregón's entrenchments and modern machine guns, and the villista advance was first checked, then repulsed. In the Second battle of Celaya, Obregón lost one of his arms to villista artillery. Nonetheless, Villa lost the battle.

Villa retrenched to Chihuahua and attempted to refinance his revolt by having a firm in San Antonio, Texas, mint more fiat currency. But the effort met with limited success, and the value of Villa's paper pesos dropped to a fraction of their former value as doubts grew about Villa's political viability. Villa began ignoring the counsel of the most valuable member of his military staff, Felipe Ángeles, and eventually Ángeles left for exile in Texas. Despite Carranza's unpopularity, Carranza had an able general in Obregón and most of Mexico's military power, and unlike Huerta, was not being hampered by interference from the United States.

Split with the United States and the punitive expedition

The United States, following the diplomatic policies of Woodrow Wilson, who believed that supporting Carranza was the best way to expedite establishment of a stable Mexican government, refused to allow more arms to be supplied to Villa, and allowed Mexican constitutionalist troops to be relocated via U.S. railroads. Villa, possibly out of a sense of betrayal, began to attack Americans. He was further enraged by Obregón's use of searchlights, powered by American electricity, to help repel a villista night attack on the border town of Agua Prieta, Sonora, on November 1, 1915. In January 1916, a group of villistas attacked a train on the Mexico North Western Railway, near Santa Isabel, Chihuahua, and killed 18 American employees of the ASARCO company.

Cross-border attack on New Mexico

On March 9, 1916, Villa ordered 1,500 (disputed, one official U.S. Army report stated "500 to 700") Mexican raiders, reportedly led by villista general Ramón Banda Quesada, to make a cross-border attack against Columbus, New Mexico, in response to the U.S. government's official recognition of the Carranza regime and for the loss of lives in battle due to defective bullets purchased from the United States.[6] They attacked a detachment of the 13th U.S. Cavalry, seized 100 horses and mules, burned the town, killed 10 soldiers and 8 civilian residents, and took much ammunition and weaponry.

The Hunt for Pancho Villa

United States President Woodrow Wilson responded to the Columbus raid by sending 6,000 troops under General John J. Pershing to Mexico to pursue Villa. (Wilson also dispatched several divisions of Army and National Guard troops to protect the southern U.S. border against further raids and counterattacks.) In the U.S., this was known as the Punitive or Pancho Villa Expedition. During the search, the United States launched its first air combat mission with eight airplanes.[7] At the same time Villa, was also being sought by Carranza's army. The U.S. expedition was eventually called off after failing to find Villa, and Villa successfully escaped from both armies.

Later life and assassination

After the Punitive Expedition, Villa remained at large, but never regained his former stature or military power. Carranza's loss of Obregon as chief general in 1917, and his preoccupation with the continuing rebellion of the Zapatista and Felicista forces in the south (much closer to Mexico City and perceived as the greater threat), prevented him from applying sufficient military pressure to extinguish the Villa nuisance. Few of the Chihuahuans who could have informed on Villa were inclined to cooperate with the Carranza regime. Villa's last major raid was on Ciudad Juárez in 1919.

In 1920, Villa negotiated peace with new President Adolfo de la Huerta and ended his revolutionary activity. He went into semi-retirement, with a detachment of 50 dorados for protection, at the hacienda of El Canutillo.[8] He was assassinated three years later (1923) in Parral, Chihuahua, in his car. The assassins were never arrested, although a Durango politician, Jesús Salas Barraza, publicly claimed credit. While there is some circumstantial evidence that Obregón or Plutarco Elías Calles was behind the killing, Villa made many enemies over his lifetime, who would have had motives to murder him.[9] Today, Villa is remembered by many Mexicans as a folk hero.

According to Western folklore, grave robbers decapitated his corpse In 1926.[10]

A purported death mask alleged to be Villa's was hidden at the Radford School in El Paso, Texas, until the 1970s, when it was sent to the National Museum of the Revolution in Chihuahua; other museums have ceramic and bronze representations that do not match this mask.[11]

The location of the remainder of Villa's corpse is in dispute. It may be in the city cemetery of Parral, Chihuahua,[12] or in Chihuahua City, or in the Monument of the Revolution in Mexico City.[13] Tombstones for Villa exist in both places. A pawn shop in El Paso, Texas, claims to be in possession of Villa's preserved trigger finger.[14]

His final words were reported as: "No permitas que esto acabe así. Cuentales que he dicho algo." This translates as: "Don't let it end like this. Tell them I have said something."

Villa's battles and military actions

- Battle of Ciudad Juárez (twice, in 1911 and 1913, won both times)

- Battle of Tierra Blanca (1913 won)

- Battle of Chihuahua (1913 won)

- Battle of Ojinaga (1913 won)[15]

- Battle of Torreón and Battle of Gómez Palacio (1914 won)

- Battle of Saltillo (1914 won)

- Battle of Zacatecas (1914 won)

- Battle of Celaya (1915 lost)

- Attack on Agua Prieta (1915 lost)

- Attack on Columbus, New Mexico (1916 lost)

German involvement in Villa's later campaigns

Prior to the Villa-Carranza split in 1915, there is no credible evidence that Villa cooperated with or accepted any help from the German government or agents. Villa was supplied arms from the U.S., employed American mercenaries and doctors, was portrayed as a hero in the U.S. media, and did not object to the 1914 U.S. naval occupation of Veracruz (Villa's observation was that the occupation merely hurt Huerta). The German consul in Torreón made entreaties to Villa, offering him arms and money to occupy the port and oil fields of Tampico to enable German ships to dock there, this offer was rejected by Villa.

Germans and German agents did attempt to interfere, unsuccessfully, in the Mexican Revolution. Germans attempted to plot with Victoriano Huerta to assist him to retake the country, and in the infamous Zimmermann Telegram to the Mexican government, proposed an alliance with the government of Venustiano Carranza.

There were documented contacts between Villa and the Germans, after Villa's split with the Constitutionalists. Principally, this was in the person of Felix A. Sommerfeld, (noted in Katz's book), who in 1915, funneled $340,000 of German money to the Western Cartridge Company to purchase ammunition. However, the actions of Sommerfeld indicate he was likely acting in his own self interest (he supposedly was paid a $5,000 per month stipend for supplying dynamite and arms to Villa, a fortune in 1915, and acted as a double agent for Carranza). Villa's actions were hardly that of a German catspaw, rather, it appears that Villa only resorted to German assistance after other sources of money and arms were cut off.[16]

At the time of Villa's attack on Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916, Villa's military power had been marginalized and was mostly an impotent nuisance (he was repulsed at Columbus by a small cavalry detachment, albeit after doing a lot of damage), his theater of operations was mainly limited to western Chihuahua, he was persona non grata with Mexico's ruling Carranza constitutionalists, and the subject of an embargo by the United States, so communication or further shipments of arms between the Germans and Villa would have been difficult. A plausible explanation of any Villa-German contacts after 1915, would be that they were a futile extension of increasingly desperate German diplomatic efforts and villista pipe dreams of victory as progress of their respective wars bogged down. Villa effectively did not have anything useful to offer in exchange for German help at that point.

When weighing claims of Villa conspiring with Germans, one should take into account that at the time, portraying Villa as a German sympathizer served the propaganda ends of both Carranza and Wilson.

The use of Mauser rifles and carbines by Villa's forces does not necessarily indicate any German connection, these were widely used by all parties in the Mexican Revolution, Mauser longarms being enormously popular weapons and, had been standard issue in the Mexican Army, which had begun adopting 7 mm Mauser system arms as early as 1895.

Legacy

Villa's generalship was noted for the speed of its movement of troops (by railroad), the use of an elite cavalry unit called Los dorados ("the golden ones"), artillery attacks, and recruitment of the enlisted soldiers of defeated enemy units. He earned the nickname El Centauro del Norte (The Centaur of the North). Many of Villa's tactics and strategies were adopted by later twentieth century revolutionaries. He was one of the major (and most colorful) figures of the first successful popular revolution of the twentieth century, Villa's notoriety attracted journalists, photographers, and military freebooters (of both idealistic and opportunistic stripes) from far and wide.

Pancho Villa's legacy includes several films in which he played himself. As one of the major (and most colorful) figures of the first successful popular revolution of the twentieth century, Villa's notoriety attracted journalists, photographers, and military freebooters (of both idealistic and opportunistic stripes) from far and wide.

Villa's non-military revolutionary aims, unlike those of Emiliano Zapata's and the Zapatista Plan de Ayala, were not clearly defined which, generally, was true of the revolution itself. Villa spoke vaguely of creating communal military colonies for his troops. The Revolution was a cry for freedom but it was unlike the American Revolution from which the United States emerged, based on a clear ideology and view of what kind of society ought to be built. Successive governments in Mexico have failed to deal with such issues as the huge differential in wealth and property ownership between the elite and non-elite, or the rights of the indigenous peoples. Regardless of who has power, the poor have remained poor and the ricer have grown richer. Villa's revolution overthrew the dictatorial rule of Porfirio Díaz but the different players, among whom there were socialists and anarchists and nationalists and those who simply wanted to remove a tyrant, had no common vision.

Pancho Villa in films, video, and television

Villa represented in films by himself in 1912, 1913, and 1914. Many other actors have represented him, such as:

- Antonio Aguilar (1993) La sangre de un valiente

- Victor Alcocer (1955) El siete leguas

- Pedro Armendáriz (1950, 1957, 1960 twice)

- Pedro Armendáriz, Jr. (1989) Old Gringo

- Antonio Banderas (2003) And Starring Pancho Villa as Himself

- Wallace Beery (1934) Viva Villa!

- Maurice Black (1937) Under Strange Flags

- Gaithor Brownne (1985) Blood Church

- Yul Brynner (1968) Villa Rides

- Peter Butler (2000) From Dusk Till Dawn 3: The Hangman's Daughter

- Leo Carrillo (1949) Pancho Villa Returns

- Phillip Cooper (1934) Viva Villa! (Pancho Villa as a boy)

- Hector Elizondo (1976) Wanted: The Sundance Woman (TV)

- Freddy Fender (1977) She Came to the Valley

- Guillermo Gil (1987) Senda de Gloria

- Rodolfo Hoyos, Jr. (1958) Villa!!

- George Humbert (1918) Why America Will Win

- Carlos Roberto Majul (1999) Ah! Silenciosa

- José Elías Moreno (1967) El Centauro Pancho Villa

- Mike Moroff (1999) The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones: Spring Break Adventure

- Jesús Ochoa (1995), Entre Pancho Villa y una mujer desnuda

- Ricardo Palacios (1967) Los Siete de Pancho Villa

- Alan Reed (1952) Viva Zapata!

- Jorge Reynoso (1982) Red Bells: Mexico in Flames

- Telly Savalas (1971) Pancho Villa!

- Domingo Soler (1936), ¡Vámonos con Pancho Villa!

- Juan F. Triana (1935) El Tesoro de Pancho Villa

- Jose Villamor (1980) Viva Mexico (TV)

- Heraclio Zepeda (1973) Reed, Mexico insurgente

- Raoul Walsh (1912, 1914) The Life of General Villa

Notes

- ↑ George Brecher, Mexican Military Might. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ↑ Jim Tuck, Usurper: The Dark Shadow of Victoriano Huerta from Mexico Connect. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Charles Burress, "Wells Fargo's Hush-Hush Deal With Pancho Villa," San Francisco Chronicle, May 5, 1999, Firm helped ransom silver bars he stole to finance his rebellion. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ John S.D. Eisenhower, Intervention: The United States and the Mexican Revolution, 1913-1917 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1993), 58.

- ↑ University of Texas Library, Map of Constitutionalist Army Battles. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ BYU Library, Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca, Villa's Raid on Columbus, New Mexico. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Michigan State University, U.S. Army Airplane arriving at a Village in Mexico, Online photo. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Glenn P. Willeford, The Life of General Francisco Villa at Ex-Hacienda La Purísima Concepción de El Canutillo, The Life of General Francisco Villa. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Brad Rath, The Personal History of Pancho Villa and Its Effects on Mexican History, at Historical Text Archive. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Hadleen Braddy, "The Head of Pancho Villa," Western Folklore 19(1): 25–33.

- ↑ John MacCormack, "Questions Begin to Arise Over Death Mask of Pancho Villa," San Antonio Express, July 2006, Online at BanderasNews. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Find-A-Grave Memorial, Pancho Villa (1877-1923)—Original name: Doroteo Arango, Pancho Villa. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Find-A-Grave Memorial, Pancho Villa—picture, Pancho Villa. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ KVIA, For Sale: Pancho Villa's trigger finger. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Pancho Villa Home Page, The Battle of Ojinaga. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Jim Tuck, Pancho Villa as a German Agent? from MexicoConnect. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Braddy, Hadleen. "The Head of Pancho Villa." Western Folklore 19, no. 1 (January 1960): 25–33.

- Burress, Charles. "Wells Fargo's Hush-Hush Deal With Pancho Villa." San Francisco Chronicle, September 30, 2022.Firm helped ransom silver bars he stole to finance his rebellion. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- BYU Library. Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca. Villa's Raid on Columbus, New Mexico. Retrieved September 30, 2022

- Eisenhower, John S.D. Intervention: The United States and the Mexican Revolution, 1913-1917. New York: W. W. Norton, 1993.

- Find-A-Grave Memorial. Pancho Villa (1877-1923)—Original name: Doroteo Arango. Pancho Villa. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- Find-A-Grave Memorial. Pancho Villa—picture. Pancho Villa. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- Howell, Jeff. Pancho Villa, Outlaw, Hero, Patriot, Cutthroat: Evaluating the Many Faces of. from Historical Text Archive. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- Katz, Friedrich. The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0804730466.

- MacCormack, John. "Questions Begin to Arise Over Death Mask of Pancho Villa." San Antonio Express. July 2006. Online at BanderasNews. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- Rath, Brad. The Personal History of Pancho Villa and Its Effects on Mexican History. at Historical Text Archive. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- University of Texas Library. Battles.Map of Constitutionalist Army Battles. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- Villa, Guadalupe, and Rosa Helia Villa (eds.). Retrato autobiográfico, 1894-1914. Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2003. ISBN 9681913116.

External links

All links retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Statue of Pancho Villa, the Mexican Revolutionary Leader in Tucson, Arizona, United States.

- Pancho Villa Encyclopædia Britannica.

| Preceded by: Salvador R. Mercado |

Governor of Chihuahua 1913 - 1914 |

Succeeded by: Manuel Chao |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.