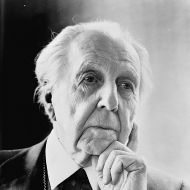

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was one of the most prominent and influential architects of the twentieth century. Wright is easily America's most famous architect. He left behind a rich collection of beautiful buildings, including 362 houses, of which about 300 survive.

From his childhood Wright acquired a deep and almost mystical love of nature. Like the Arts and Crafts Movement, his designs reflect the observation of the beauty of natural things. He created a new language for architecture of the modern age.

Wright's enduring legacy is a highly innovative, architectural style that strictly departed from European influences to create a purely American form, one that actively promoted the idea that buildings can exist in harmony with the natural environment. Over his long career, Wright designed a diverse collection of structures, both public and private, including the home known as Fallingwater, the Johnson Wax Building, and New York's Guggenheim Museum.

Early years

Frank Lloyd Wright was born in the agricultural town of Richland Center, Wisconsin, and was brought up with strong Unitarian and transcendental principles. Eventually he would design the Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois. As a child he spent a great deal of time playing with the kindergarten educational blocks designed by Friedrich Wilhelm August Fröbel given to him by his mother. These consisted of various geometrically shaped blocks that could be assembled in combinations to form three-dimensional compositions. Wright, in his autobiography, talks about the influence of these exercises on his approach to design. Many of his buildings are notable for the geometrical clarity they exhibit.

Wright commenced his formal education in 1885 at the University of Wisconsin School of Engineering. He took classes part-time for two years while apprenticing under a local builder who was also a professor of civil engineering. In 1887, Wright left the university without earning a degree. Many years later, in 1955, he was granted an honorary doctorate of fine arts from the university.

After his college years, Wright moved to Chicago, Illinois, where he joined the architectural firm of Joseph Lyman Silsbee. Within the year, he had left Silsbee to work for the firm of Adler and Sullivan. Beginning in 1890, he was assigned all residential design work for the firm. In 1893, after a falling-out that probably concerned the work he had done outside the office, Wright left Adler and Sullivan to establish his own practice and home in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park. He had completed nearly 50 projects by 1901, including many houses in his hometown.

Between 1900 and 1910, his residential designs were "Prairie Houses"—so-called because the design is considered to complement the land around Chicago—extended, low buildings with shallow, sloping roofs, clean skylines, suppressed chimneys, overhangs and terraces, using unfinished materials. These houses are credited with being the first examples of the "open plan."

The manipulation of interior space in residential and public buildings, such as the Unitarian Unity Temple in Oak Park, are hallmarks of the Wright style. Wright believed that architectural design engages the human ideals for family life and work with the art of building. Many examples of this work can be found in Buffalo, New York, resulting from a friendship between Wright and an executive from the Larkin Soap Company, Darwin D. Martin.

In 1902, the Larkin Company decided to build a new administration building. The architect came to Buffalo and designed not only the first sketches for the Larkin Administration Building (now demolished), but also three homes for the company's executives:

- George Barton House 1903

- Darwin D. Martin House 1904

- William Heath House 1905

The houses considered the masterpieces of the late "prairie period" (1907–9) include the Frederick Robie House and the Avery and Queene Coonley House, both in Chicago. The Robie House, with its soaring, cantilevered roof lines, supported by a 110-foot-long channel of steel, is the most dramatic. Its living and dining areas form virtually one uninterrupted space. This building had the most influence on young European architects after World War I and is called the "cornerstone of modernism." In 1910, the "Wasmuth Portfolio" was published, and created the first major exposure of Wright's work in Europe.

Taliesin and beyond

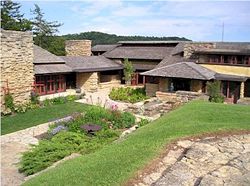

Wright designed his own home-studio complex, named "Taliesin," after the sixth century Welsh poet, whose name literally means "shining brow." This home was begun near Spring Green, Wisconsin, in 1911 and has been modified and expanded many times over. The complex was a distinctive, low, one-story, U-shaped structure with views over a pond on one side and Wright's studio on the opposite side. Taliesin was twice destroyed by fire; the current building there is called Taliesin III.

Wright visited Japan, first in 1905, and Europe in 1909 and 1910, opening a Tokyo office in 1916. In 1938, he designed his winter retreat in Arizona, named Taliesin West; the retreat, like much of Wright's architecture, blends organically with the surrounding landscape.

In Tokyo, Wright designed his famous Imperial Hotel, completed in 1922 after beginning construction in 1916. On September 1, 1923, one of the worst earthquakes in modern times hit Tokyo and its surrounding area. The Great Kantō earthquake completely leveled Tokyo, and effects from the earthquake caused a large tsunami, destructive tornadoes, and fires in the city. A legend grew out of this disaster that Wright's Imperial Hotel was the only large structure to survive the destruction, but in fact this was far from true.

"Usonian" houses, organic architecture

Wright is responsible for a series of extremely original concepts of suburban development united under the term Broadacre City. He proposed the idea in his book, The Disappearing City, in 1932, and unveiled a very large (12 by 12 feet) model of this community of the future, showing it in several venues in the following years. He went on developing the idea until his death. It was also in the 1930s that Wright designed many of his "Usonian" houses; essentially designs for middle-class people that were based on a simple geometry yet elegantly done and practical. He would later use such designs in his First Unitarian Meeting House built in Madison, Wisconsin, between 1947 and 1950.

His most famous private residence was constructed from 1935 to 1939, Fallingwater, for Mr. and Mrs. E.J. Kaufmann, Sr. at Mill Run, Pennsylvania. It was designed according to Wright's desire to place the occupants close to the natural surroundings, with a stream running under part of the building. The construction is a series of cantilevered balconies and terraces, using limestone for all verticals and concrete for the horizontals. From his memory, Wright knew every tree and rock on that site and from his office he worked out the preliminary design of the residence within a day. Fallingwater is a poem of glass, stone, and concrete, a dialog of human space in nature. It is considered to be the greatest modern house of the twentieth century.

Personal life

Wright's personal life was a colorful one that frequently made news headlines. He married three times: Catherine Lee Tobin in 1889, Miriam Noel in 1922, and Olga Milanov Hinzenberg (Olgivanna) in 1928. Wright and Olgivanna had earlier been accused of violating the Mann Act (immoral actions, probably suggesting an extra-marital affair) and arrested in October 1925. The charges were dropped in 1926.

Olgivanna had been living as a disciple of Armenian mystic G. I. Gurdjieff, and her experiences with Gurdjieff influenced the formation and structure of Wright's Taliesin Fellowship in 1932. The meeting of Gurdjieff and Wright is explored in Robert Lepage's The Geometry Of Miracles. Olgivanna continued to run the Fellowship after Wright's death, until her own death in Scottsdale, Arizona in 1985. Despite being a high-profile architect and almost always in demand, Wright would find himself constantly in debt, thanks in part to his lavish lifestyle.

Legacy

Wright died on April 9, 1959, having designed an enormous number of significant projects including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, a building which occupied him for 16 years (1943 through 1959) and is probably his most recognized masterpiece.

The building rises as a warm, beige spiral from its site on Fifth Avenue; its interior is similar to the inside of a seashell. Its unique, central geometry was meant to allow visitors to experience the Guggenheim's collection of nonobjective, geometric paintings with ease by taking an elevator to the top level and then viewing artworks by walking down the slowly descending, central, spiral ramp.

Wright built 362 houses; as of 2005, about 300 survive. Four have been lost to forces of nature: the waterfront house for W. L. Fuller in Pass Christian, Mississippi, destroyed by Hurricane Camille in August 1969; the Louis Sullivan Bungalow of Ocean Springs, Mississippi, destroyed by Hurricane Katrina in 2005; and the Arinobu Fukuhara House (1918) in Hakone, Japan, destroyed in the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923. The Ennis House in California has also been damaged by earthquake and rain-induced ground movement. While a number of the houses are preserved as museum pieces and millions of dollars are spent on their upkeep, other houses have trouble selling on the open market due to their unique designs, generally small size, and outdated features.

As buildings age, their structural deficiencies are increasingly revealed, and Wright's designs have not been immune from the passage of time. Some of his most daring and innovative designs have required major structural repair, and the soaring cantilevered terraces of Fallingwater are but one example. Some of these deficiencies can be attributed to Wright's pushing of materials beyond the state of the art, others to sometimes less than rigorous engineering, and still others to the natural wear and tear of the elements over time.

In 2000, "Work Song: Three Views of Frank Lloyd Wright," a play based on the relationship between the personal and working aspects of Wright's life, debuted at the Milwaukee Repertory Theater.

One of Wright's sons, Frank Lloyd Wright, Jr., known as Lloyd Wright, was also a notable architect in Los Angeles. Lloyd Wright's son, (and Wright's grandson) Eric Lloyd Wright, is currently an architect in Malibu, California.

Some other works

- Arthur Heurtley House, near Oak Park, Illinois, 1902

- Beth Sholom Synagogue, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1954

- William H. Winslow House, near River Forest, Illinois, 1894

- Ward W. Willits House, Highland Park, Illinois, 1901

- Susan Lawrence Dana House, The Dana-Thomas House Springfield, Illinois, 1902–1904

- George Barton House, Buffalo, New York, 1903

- Darwin D. Martin House and Gardener's Cottage, Buffalo, New York, 1904, 1905

- Burton & Orpha Westcott House, Springfield, Ohio, 1904

- William Heath House, Buffalo, New York, 1905

- The Larkin Administration Building, Buffalo, New York, 1906

- Unity Temple, Oak Park, IL, 1906

- Avery Coonley House, Buffalo, New York, 1908

- Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois, 1909

- Moe House, Gary, Indiana, 1909

- Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, 1915–1922; demolished, 1968, lobby and pool reconstructed in 1976 in at Meiji Mura, near Nagoya, Japan

- Wynant House, Gary, Indiana, 1915

- Aline Barnsdall House (Hollyhock House), Los Angeles, California, 1917

- Charles Ennis House, Los Angeles, CA, 1923

- Darwin D. Martin Residence, (Graycliff Estate), Buffalo, New York (Derby, NY), 1927

- Ras-el-Bar, Damietta, Egypt, 1927

- Johnson Wax Headquarters, Headquarters, Racine, Wisconsin, 1936

- Paul R. Hanna House ("Honeycomb House"), Stanford, California, begun 1936

- Herbert F. Johnson House ("Wingspread"), Wind Point, Wisconsin, 1937

- Frank Lloyd Wright's Florida Southern College Works, 1940s

- First Unitarian Society, Shorewood Hills, Wisconsin, 1947

- V.C. Morris Gift Shop, San Francisco, California, 1948

- Price Tower, Bartlesville, Oklahoma, 1952

- R.W. Lindholm Service Station Cloquet, Minnesota 1956

- Marin County Civic Center, San Rafael, CA, 1957–66 (featured in the movies Gattaca and THX 1138)

- Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church, Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, designed in 1956, completed in 1961

- Marin County Civic Center, San Rafael, California, 1957–1966

- Blue Sky Mausoleum, Buffalo, New York, 2004

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Selected books and articles on Wright’s philosophy

- Lind, Carla. The Wright Style. Simon & Schuster, 1992. ISBN 0671749595

- Hoffmann, Donald. Understanding Frank Lloyd Wright's Architecture. Dover Publications, 1995. ISBN 048628364X

- Wright, Frank Lloyd, & Patrick Joseph Meehan. Truth Against the World: Frank Lloyd Wright Speaks for an Organic Architecture. Wiley, 1987. ISBN 0471845094

Biographies on Wright

- Gill, Brendan. Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright. Putnam, 1987. ISBN 0399132325

- Secrest, Meryle. Frank Lloyd Wright. Knopf, 1992. ISBN 0394564367

- Twombly, Robert C. Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture. New York: Wiley, 1979. ISBN 0471034002

Selected survey books on Wright’s work

- Levine, Neil, & Frank Lloyd Wright. The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 0691033714

- Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks & David Larkin. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks. Rizzoli in association with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, 1993. ISBN 0847817156

- Storrer, William Allin, & Frank Lloyd Wright. The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, a Complete Catalog. MIT Press, 1974. ISBN 0262190974

External links

All links retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

- Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust

- Frank Lloyd Wright. Designs for an American Landscape 1922-1932

- Frank Lloyd Wright: A film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.