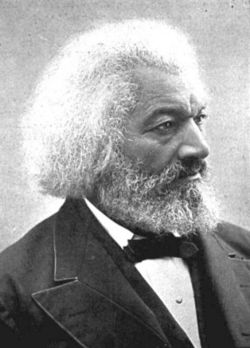

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass, born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, (February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American abolitionist, newspaper publisher, orator, author, statesman, and reformer. Called "The Sage of Anacostia" and "The Lion of Anacostia," Douglass was among the most prominent African-Americans of his time, and one of the most influential lecturers and authors in American history.

Frederick Douglass was a key figure in the abolition of slavery in the United States. His motivation was based on his early life as a slave and his conviction, rooted in Holy Scripture, that all people are equal in the eyes of God. Douglass was a firm believer in the equality of all people, whether black, female, or recent immigrant. He spent his life advocating the brotherhood of all humankind. One of his favorite quotations was, "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."

Life as a slave

Frederick Douglass was born a slave in Talbot County, Maryland, near Hillsborough, 12 miles from Easton. He was separated from his mother, Harriet Bailey, when he was still an infant. As slaves, a mother and her children were often separated. Slave owners knew that breaking the family bonds was integral to breaking the slave's spirits. Therefore this practice was often followed. In later life, Frederick would often recount the times his mother walked 12 miles at night to spend half an hour with him. He wrote that "a true mother's heart was hers" and "I take few steps in life without feeling her presence." She died when Frederick was nine years old. He never knew anything about the identity of his father, other than that he was a white man, although some believe that his master, Captain Aaron Anthony, was his father. When Anthony died, Frederick was given to Mrs. Lucretia Auld, wife of Captain Thomas Auld. The young man was sent to Baltimore to serve the Captain's brother, Hugh Auld. Later, Douglass declared this an “Act of Providence.” He wrote, "going to Baltimore laid the foundation, and opened the gateway, to all my subsequent prosperity. I have ever regarded it as the first plain manifestation of that kind providence which has ever since attended me, and marked my life with so many favors. This good spirit was from God, and to him I offer thanksgiving and praise."

Early education

When Frederick was ten, Hugh Auld's wife, Sophia, broke the law by teaching him to read. When Mr. Auld discovered this, he strongly disapproved, saying that if a slave learns to read, he would become dissatisfied with his condition and desire freedom; Frederick later referred to this as the first anti-abolitionist speech he had ever heard. Another turning point in his young life happened when he purchased a copy of the book The Columbian Orator, by Caleb Bingham, A.M. It was the first book he ever owned. Frederick also studied and memorized classic speeches by the Roman orator Cicero in order to find his own voice.

During this period, Frederick became attached to a deeply religious man known to us as "Uncle Lawson," who became a spiritual father to him. Young Frederick took every opportunity to be with Lawson, who told him that it was possible for him to be delivered from bondage. Douglass fervently prayed to God that it so transpire. This turn of events would not have pleased slave owners, who preferred and appreciated preachers who taught that slavery was the benevolent creation of God and that faithful and obedient slaves would be rewarded in heaven. This was not how Frederick interpreted Christianity. For him it meant the equality of all people before God and deliverance from bondage in this life. Religion taught Douglass to value himself, love others, and work to achieve freedom. Christianity's ideals helped inspire his work and guide his actions.

The fight with Edward Covey

By 1834, Frederick was back on the farm in Talbot County. Gone were his opportunities to learn among the streets and wharves of Fells Point in Baltimore. Now began the great test of his young life. Hugh Auld rented Frederick out to a farmer named Edward Covey, a "slave breaker" of extraordinary cruelty. Sixteen-year-old Frederick was indeed nearly broken psychologically by his ordeal under Covey, but finally rebelled against the beatings and fought back. Covey lost out on a confrontation with Frederick and never tried to beat him again. This incident was kept under wraps possibly because Covey was afraid the news of Frederick's victory would ruin his reputation as a "slave breaker," or he was simply ashamed of his defeat.

Escape to freedom

By 1837, Frederick was back in Fells Point and had joined the East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society, a debating club of free blacks. Frederick was the only slave there. Through the society, he met a free African-American housekeeper, Anna Murray. Anna Murray sold a poster bed to buy sailor's papers needed for Frederick's escape. On September 3, 1838, Frederick boarded a train in Baltimore on his way to freedom from slavery, dressed in a sailor's uniform and carrying identification papers provided by a free black seaman. Though he did not match the physical description in the papers, the conductor gave them only a casual glance. From Baltimore, Frederick made his way to Wilmington, Delaware. He had to continue north, as both Maryland and Delaware were slave states. He went through Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and then onto New York City. He wrote to Anna from there and they were married on September 15. They were warned that New York was not safe for runaways, so they moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts. This was by no means one of the most creative escapes of a slave; Henry "Box" Brown mailed himself (as a parcel) from Virginia to Philadelphia in a journey taking 26 hours. It was at this time that Frederick (Bailey) changed his name to Frederick Douglass, adopting the name of a heroic character in Sir Walter Scott's novel The Lady of the Lake.

Career

Douglass continued reading. He joined various organizations in New Bedford, including a black church. He regularly attended Abolitionist meetings. He subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison's weekly journal, the Liberator, and in 1841, he heard Garrison speak at the Bristol Anti-Slavery Society's annual meeting. Douglass was inspired by Garrison, later stating, "no face and form ever impressed me with such sentiments (the hatred of slavery) as did those of William Lloyd Garrison." Garrison was likewise impressed with Douglass, and mentioned him in the Liberator.

Several days later, Douglass gave his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention in Nantucket Island. Twenty-three years old at the time, Douglass later said that his legs were shaking. He conquered his nervousness and gave an eloquent speech about his life as a slave.

In 1843, Douglass participated in the American Anti-Slavery Society's Hundred Conventions project, a six-month tour of meeting halls throughout the East and Midwest of the United States. Not everyone appreciated his speaking; an angry mob beat Douglass and broke his hand in Pendleton, Indiana, in September 1844. In 1845, he published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave. The popularity of his book forced him out of the country. By 1847, he was back in the States and settled in Rochester, New York. In 1848, he participated in the Seneca Falls Convention, the birthplace of the American feminist movement, and was a signatory of its Declaration of Sentiments.

Douglass later became the publisher of a series of newspapers: The North Star, Frederick Douglass Weekly, Frederick Douglass' Paper, Douglass' Monthly, and New National Era. The motto of The North Star was "Right is of no sex—Truth is of no color—God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren."

Douglass' work spanned the years prior to and during the Civil War. He was acquainted with the radical abolitionist Captain John Brown, but did not approve of Brown's plan to start an armed slave revolt. Douglass believed that the Harpers Ferry attack on federal property would enrage the American public. After John Brown's Raid, Douglass praised him, saying that he was willing to live to free the slaves, but Brown was willing to give his life. Because of his contact with Brown, Douglass had to leave the country again. In March 1860, Douglass' youngest daughter, Annie, died at age eleven in Rochester, New York, while he was still in England. Upon learning of this, Douglass returned immediately. He arrived the following month, taking the northern route through Canada to avoid detection. The Douglass' home was close to the Canadian border and one of the last stops on the Underground Railroad.

Douglass saw the Civil War as a struggle between freedom and slavery. For him, the sin of slavery could only be ended if Americans were forced to shed their blood. He especially wanted black soldiers to fight on behalf of the Union, so that slaves could help earn their freedom. President Abraham Lincoln's original concern was in saving the Union, but on January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was promulgated and the first official black troops were registered. Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 on the treatment of black soldiers, and later with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of black suffrage. Douglass was in Rochester when he heard of Lincoln's assassination and said, "President Lincoln died as the father of his people and would be mourned by them as long as one remained in America who had been a slave." Mary Todd Lincoln gave Douglass the President's favorite cane as a token of their enduring friendship.

Autobiography

Douglass' most well-known work is his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, which was published in 1845. Critics frequently attacked the book as inauthentic, not believing that an uneducated black man could possibly have produced so eloquent a piece of literature. Except for his brief tutelage under Sophia Auld, Douglass was completely self-taught. The book was an immediate bestseller and received overwhelmingly positive critical reviews. Within three years of its publication, it had been reprinted nine times with 11,000 copies circulating in the United States; it was also translated into the French and Dutch.

The book's success had an unfortunate side effect: His friends and mentors feared that the publicity would draw the attention of his ex-owner, Hugh Auld, who could try to get his "property" back. They encouraged him to go on a tour in Ireland, as many other ex-slaves had done in the past. He set sail on the Cambria for Liverpool on August 16, 1845, and arrived in Ireland when the Irish famine was just beginning.

Travels to Europe

Douglass spent two years in the British Isles and gave several lectures, mainly in Protestant churches. He remarked that in the United Kingdom he was treated not "as a color, but as a man."

He met and befriended the Irish nationalist Daniel O'Connell. When Douglass visited Scotland, the members of the Free Church of Scotland, whom he had criticized for accepting money from U.S. slave-owners, demonstrated against him with placards that read "Send back the nigger." English friends purchased his freedom and urged him to stay in the United Kingdom. But Douglass longed for his family and knew his true mission was to help his enslaved brothers and sisters back in the United States.

Douglass and Anna had five children; two of them, Charles and Rossetta, helped produce his newspapers. Charles and another son, Lewis, served as soldiers during the Civil War.

The North Star problem

In 1847, Douglass founded a Rochester, New York paper called The North Star. One evening, a group of men burst into the office and started to approach menacingly toward one of the printing presses, but Douglass beat them to it. "You can smash this place and I'll open my paper elsewhere. Stop me, and others will take my place. You came here to destroy my paper? Let me help you." Douglass smashed the printing press himself. "You can smash machines, but you can't smash ideas." Thus, Douglass successfully diffused the confrontation.

The Civil War

In 1851, Douglass merged the North Star with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party Paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper, which was published until 1860. Douglass came to agree with Smith and Lysander Spooner that the U.S. Constitution is an anti-slavery document, reversing his earlier belief that it was pro-slavery, a view he had shared with William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison had publicly demonstrated his opinion of the Constitution by burning copies of it. Douglass' change of position on the Constitution was one of the most notable incidents of a division that emerged in the abolitionist movement after the publication of Spooner's book The Unconstitutionality of Slavery in 1846. This shift in opinion, as well as some other political differences, created a rift between Douglass and Garrison. Douglass further angered Garrison by saying that the Constitution could and should be used as an instrument in the fight against slavery. With this, Douglass began to assert his independence from Garrison's views. Garrison saw the North Star as being in competition with the National Anti-Slavery Standard and Marius Robinson's Anti-slavery Bugle.

By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous black men in the country, known for his oratories on the condition of the black race, and other issues such as women's rights. He was the first black man to visit a president on equal footing. Whenever President Lincoln saw him, he would say, "Here is my friend, Frederick Douglass." The President once kept Governor Buckingham of Connecticut waiting because he wanted a long talk with Douglass. During the last two years of the war about 200,000 African-Americans served in Union regiments. When given the chance to fight, blacks proved as brave as anyone. More than 30,000 died fighting for freedom and the Union.

The Reconstruction era

After the Civil War, Douglass held a number of important political positions. He served as President of the failed Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank; as marshal of the District of Columbia; as minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti; and as chargé d'affaires for Santo Domingo. After two years, he resigned his ambassadorship due to disagreements with U.S. government policy. In 1872, he moved to Washington, D.C after his house on South Avenue in Rochester, New York burned down—arson was suspected. A complete set of The North Star was lost in the fire.

In 1868, Douglass supported the presidential campaign of Ulysses S. Grant. The Klan Act and the Enforcement Act were signed into law by President Grant. Grant used their provisions vigorously, suspending habeas corpus in South Carolina and sending troops there and into other states; under his leadership, over 5,000 arrests were made and the Ku Klux Klan was dealt a serious blow.

Grant's vigor in disrupting the Klan made him unpopular among many whites, but Frederick Douglass praised him. An associate of Douglass wrote of Grant that African-Americans "will ever cherish a grateful remembrance of his name, fame and great services." The conflict was not limited to the KKK. Racist groups like the Knights of the White Camellia and the White League also played a part. From 1869 until 1893, Douglass served as an important official (and the only black) in the inauguration of every Republican president.

Later life

In 1877, Frederick Douglass purchased his final home in Washington D.C., on a hill overlooking the Anacostia River. He named it Cedar Hill (also spelled CedarHill). He expanded the house from 14 to 21 rooms. One year later, Douglass expanded his property to 15 acres (61,000 m²), with the purchase of adjoining lots. The home is now the location of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

After the disappointments of Reconstruction, many African Americans, known as Exodusters, moved to Kansas to form all-black towns. Douglass spoke out against the movement, urging blacks to stick it out. He was condemned and booed widely by black audiences.

In 1881, Douglass was appointed Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia. His wife, Anna Murray Douglass, died in 1882, which left him in a state of depression. His association with the activist Ida B. Wells brought meaning back into his life. In 1884, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a white feminist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts, Jr., an abolitionist colleague and friend of Douglass. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College (at that time Mount Holyoke Female Seminary), Pitts had worked on a radical feminist publication named Alpha while living in Washington, D.C.

Frederick and Helen Pitts Douglass faced a storm of controversy as a result of their marriage. She was a white woman and nearly 20 years younger than he. Both families recoiled; hers stopped speaking to her; his was bruised, as they felt his marriage was a repudiation of their mother. But individualist feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton congratulated the couple. Douglass' response to all the controversy was, "my first wife was the color of my mother. My second wife is the color of my father." Douglass never saw the world as one in which black and white were separated. He spoke of an "instinctive consciousness of the common brotherhood of man," seeing that as human beings we all belong to one species.

The new couple traveled to England, France, Italy, Egypt, and Greece from 1886 to 1887.

In later life, Douglass determined to ascertain his birthday. He was born in February of 1817 by his own calculations, but historians have found a record indicating his birth in February of 1818. As a child, he remembered his mother calling him her “Little Valentine,” so he adopted February 14 as his birthday.

He spoke for Irish Home Rule and on the efforts of Charles Stewart Parnell. He briefly revisited Ireland in 1886. In 1892, the Haitian government appointed Douglass as its commissioner to the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition. He spoke about the growth of lynching: "Men talk of the race problem. There is no Negro problem. The problem is whether the American people have loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough, to live up to their own Constitution." Douglass was not indifferent to the sight of injustice anywhere. The outrageous way in which the Chinese were treated made him speak up on their behalf. He did the same for Native Americans, Mexicans, and Indians (from India), finding racism a product of ignorance and a host of other factors, encompassing selfishness, arrogance, aggression, and greed.

Death

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C.. During that meeting, he was brought to the platform and given a standing ovation by the audience.

Shortly after he returned home, Frederick Douglass died of a massive heart attack or stroke, in his adopted hometown of Washington D.C.. He is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Frederick Douglass [videorecording] / produced by Greystone Communications, Inc. for A&E Network; executive producers, Craig Haffner and Donna E. Lusitana.; 1997

- Frederick Douglass: when the lion wrote history [videorecording] / a co-production of ROJA Productions and WETA-TV; produced and directed by Orlando Bagwell ; narration written by Steve Fayer.; c1994

- Frederick Douglass, abolitionist editor [videorecording] / a production of Schlessinger Video Productions, a division of Library Video Company; produced and directed by Rhonda Fabian, Jerry Baber; script, Amy A. Tiehel

- Race to freedom [videorecording] : the story of the underground railroad / an Atlantis Films Limited production in association with United Image Entertainment; produced in association with the Family Channel (U.S.), Black Entertainment Television and CTV Television Network, Ltd. ; produced with the participation of Telefilm Canada, Ontario Film Development Corporation and with the assistance of Rogers Telefund ; distributed by Xenon Pictures ; executive producers, Seaton McLean, Tim Reid ; co-executive producers, Peter Sussman, Anne Marie La Traverse ; supervising producer, Mary Kahn ; producers, Daphne Ballon, Brian Parker ; directed by Don McBrearty ; teleplay by Diana Braithwaite, Nancy Trites Botkin, Peter Mohan. Publisher Santa Monica, CA: Xenon Pictures, Inc., 2001. Tim Reid as Frederick Douglass.

Books by Douglass

- A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845)

- My Bondage and My Freedom (1855)

- Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892)

- Collected Articles Of Frederick Douglass, A Slave

- Frederick Douglass : Autobiographies by Frederick Douglass, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Editor.

Books on Douglass

- Foner, Phillip S. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass. 1975.

- Burchard, Peter. Frederick Douglass: For the Great Family of Man. New York: Atheneum Books, 2003.

- Huggins, Nathan Irvin. Slave and Citizen: The Life of Frederick Douglass. New York: HarperCollins, 1980.

- Kerby, Mona. Frederick Douglass. New York: Franklin Watts, 1994.

- Miller, Douglas T. Frederick Douglass and the Fight for Freedom. New York: Facts on File Publications, 1988.

- Russell, Sharman A. Frederick Douglass: Abolitionist Editor. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1988.

- Ruuth, Marianne. Frederick Douglass: Patriot and Activist. Los Angeles: Melrose Square Publishing Company, 1991.

External links

All links retrieved May 10, 2017.

- Frederick Douglass (American Memory, Library of Congress) Includes timeline.

- Timeline of Frederick Douglass and family.

- Online Books Page (University of Pennsylvania).

- Fourth of July Speech.

- Frederick Douglass Western New York Suffragists.

- Frederick Douglass and the term "Band of Brothers".

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Frederick Douglass.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.