|

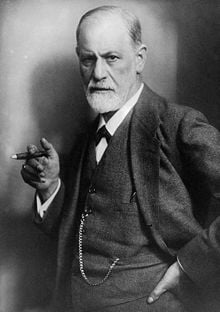

Sigmund Freud | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

May 6 1856 |

| Died | September 23 1939 (aged 83) London, England |

| Residence | Austria, (later) England |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Ethnicity | Jewish |

| Field | Neurology, Psychiatry, Psychology, Psychotherapy, Psychoanalysis |

| Institutions | University of Vienna |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Academic advisor | Jean-Martin Charcot, (later) Josef Breuer |

| Notable students | Alfred Adler, John Bowlby, Viktor Frankl, Anna Freud, Ernest Jones, Carl Jung, Melanie Klein, Jacques Lacan, Maud Mannoni, Fritz Perls, Otto Rank, Wilhelm Reich, Donald Winnicott |

| Known for | Psychoanalysis |

| Notable prizes | Goethe Prize |

| Religious stance | Atheist |

Sigmund Freud (IPA: [ˈziːkmʊnt ˈfʁɔʏt]), born Sigismund Schlomo Freud (May 6 1856 – September 23 1939), was an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist who co-founded the psychoanalytic school of psychology. Freud is best known for his theories of the unconscious mind, especially his theory of the mechanism of repression; his redefinition of sexual desire as mobile and directed towards a wide variety of objects; and his therapeutic techniques, especially his understanding of transference in the therapeutic relationship and the presumed value of dreams as sources of insight into unconscious desires.

He is commonly referred to as "the father of psychoanalysis" and his work has been highly influential in two related but distinct areas: he simultaneously developed a theory of the human mind's organization and internal operations and a theory that human behavior both conditions and results from how the mind is organized. This led him to favor certain clinical techniques for trying to help cure mental illness. He also theorized that personality is developed by a person's childhood experiences.

The modern lexicon is filled with terms that Freud popularized, including the unconscious, defense mechanisms, Freudian slips, and dream symbolism. He made a long-lasting impact on fields as diverse as literature, film, Marxist and feminist theories, philosophy, and psychology. However, his theories remain controversial and widely disputed by numerous critics, to the extent that he has been called the "creator of a complex pseudo-science which should be recognized as one of the great follies of Western civilization."

Biography

Early life

Sigmund Freud was born on May 6, 1856 to Galician Jewish[1] parents in Příbor (German: Freiberg in Mähren), Moravia, Austrian Empire, now Czech Republic. His father Jakob was 41, a wool merchant, and had two children by a previous marriage. His mother Amalié was 21. Owing to his precocious intellect, his parents favored him over his siblings from the early stages of his childhood; and despite their poverty, they offered everything to give him a proper education. Due to the economic crisis of 1857, father Freud lost his business, and the family moved first to Leipzig, Germany before settling in Vienna, Austria. In 1865, Sigmund entered the Leopoldstädter Communal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school. Freud was an outstanding pupil and graduated the Matura in 1873 with honors.

| Part of a series of articles on Psychoanalysis | |

| |

|

Constructs Important Figures Schools of Thought | |

After planning to study law, Freud joined the medical faculty at University of Vienna to study under Darwinist Karl Claus. At that time, eel life history was still unknown, and due to their mysterious origins and migrations, a racist association was often made between eels and Jews and Gypsies. In search for their male sex organs, Freud spent four weeks at the Austrian zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels without finding more than his predecessors such as Simon von Syrski. In 1876, he published his first paper about "the testicles of eels" in the Mitteilungen der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, conceding that he could not solve the matter either. Frustrated by the lack of success that would have gained him fame, Freud chose to change his course of study. Biographers like Siegfried Bernfeld wonder if and how this early episode was significant for his later work regarding hidden sexuality and frustrations.[2]

Medical school

In 1874, the concept of "psychodynamics" was proposed with the publication of Lectures on Physiology by German physiologist Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke who, in coordination with physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, one of the formulators of the first law of thermodynamics (conservation of energy), supposed that all living organisms are energy-systems also governed by this principle. During this year, at the University of Vienna, Brücke served as supervisor for first-year medical student Sigmund Freud who adopted this new "dynamic" physiology. In his Lectures on Physiology, Brücke set forth the radical view that the living organism is a dynamic system to which the laws of chemistry and physics apply.[3] This was the starting point for Freud's dynamic psychology of the mind and its relation to the unconscious.[3] The origins of Freud’s basic model, based on the fundamentals of chemistry and physics, according to John Bowlby, stems from Brücke, Meynert, Breuer, Helmholtz, and Herbart.[4] In 1879, Freud interrupted his studies to complete his one year of obligatory military service, and in 1881 he received his Dr. med. (M.D.) with the thesis "Über das Rückenmark niederer Fischarten" (on the spinal cord of lower fish species).

Freud and Psychoanalysis

Freud married Martha Bernays in 1886, after opening his own medical practice, specializing in neurology. Freud experimented with hypnosis on his hysteric patients, producing numerous scenes of "seduction" under hypnosis. His success in eliciting these scenes of seduction (far beyond what he suspected had actually occurred) caused him to later abandoned this form of treatment, in favor of a treatment where the patient talked through his or her problems. This came to be known as the "talking cure." (The term was initially coined by the patient Anna O. who was treated by Freud's colleague Josef Breuer.) The "talking cure" is widely seen as the basis of psychoanalysis.[5]

There has long been dispute about the possibility that a romantic liaison blossomed between Freud and his sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, who had moved into Freud's apartment at 19 Berggasse in 1896. This rumor of an illicit relationship has been most notably propelled forward by Carl Jung, Freud's disciple and later his archrival, who had claimed that Miss Bernays had confessed the affair to him. (This claim was dismissed by Freudians as malice on Jung's part.) It has been suggested that the affair resulted in a pregnancy and subsequently an abortion for Miss Bernays. A hotel log dated August 13, 1898 seems to support the allegation of an affair.[6]

In his forties, Freud "had numerous psychosomatic disorders as well as exaggerated fears of dying and other phobias."[7] During this time Freud was involved in the task of exploring his own dreams, memories, and the dynamics of his personality development. During this self-analysis, he came to realize the hostility he felt towards his father (Jacob Freud), who had died in 1896, and "he also recalled his childhood sexual feelings for his mother (Amalia Freud), who was attractive, warm, and protective."[8]Gerald Corey considers this time of emotional difficulty to be the most creative time in Freud's life.[7]

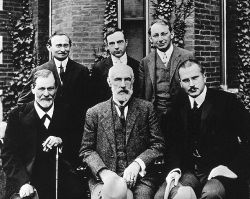

After the publication of Freud's books in 1900 and 1901, interest in his theories began to grow, and a circle of supporters developed in the following period. Freud often chose to disregard the criticisms of those who were skeptical of his theories, however, which earned him the animosity of a number of individuals, the most famous of which was Carl Jung, who originally supported Freud's ideas. They split over a variety of reasons, including Jung's insistence on addressing problems of the ego and the solely sexual nature of the Freudian unconscious. Part of the reason for their fallout was due to Jung's growing commitment to religion and mysticism, which conflicted with Freud's atheism.[9]

Last years

In 1930, Freud received the Goethe Prize in appreciation of his contribution to psychology and to German literary culture, despite the fact that Freud considered himself not a writer but a scientist (and was hoping instead for Nobel Prize). Three years later the Nazis took control of Germany and Freud's books featured prominently among those burned by the Nazis. In March 1938, Nazi Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss. This led to violent outbursts of anti-Semitism in Vienna, and Freud and his family received visits from the Gestapo. Freud decided to go into exile "to die in freedom." He and his family left Vienna in June 1938 and traveled to London.

A heavy cigar smoker, Freud endured more than 30 operations during his life due to mouth cancer. In September 1939 he prevailed on his doctor and friend Max Schur to assist him in suicide. After reading Balzac's La Peau de chagrin in a single sitting he said, "My dear Schur, you certainly remember our first talk. You promised me then not to forsake me when my time comes. Now it is nothing but torture and makes no sense any more." Schur administered three doses of morphine over many hours that resulted in Freud's death on September 23, 1939.[10] Three days after his death, Freud's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in England during a service attended by Austrian refugees, including the author Stefan Zweig. His ashes were later placed in the crematorium's columbarium. They rest in an ancient Greek urn which Freud had received as a present from Marie Bonaparte and which he had kept in his study in Vienna for many years. After Martha Freud's death in 1951, her ashes were also placed in that urn. Golders Green Crematorium has since also become the final resting place for Anna Freud and her lifelong friend Dorothy Burlingham, as well as for several other members of the Freud family.

Freud's ideas

Freud has been influential in numerous ways. He developed a new theory of how the human mind is organized and operates internally. He is largely responsible for the introduction of the impact of childhood on later adult behavior. His case histories read like novels for which there is very little precedent.

Early work

Since neurology and psychiatry were not recognized as distinct medical fields at the time of Freud's training, the medical degree he obtained after studying for six years at the University of Vienna board certified him in both fields, although he is far more well-known for his work in the latter. Freud was an early researcher on the topic of neurophysiology, specifically cerebral palsy, which was then known as "cerebral paralysis." He published several medical papers on the topic, and showed that the disease existed far before other researchers in his day began to notice and study it. He also suggested that William Little, the man who first identified cerebral palsy, was mistaken about lack of oxygen during the birth process as the etiology. Instead, he suggested that complications in birth were only a symptom of the problem. It was not until the 1980s that Freud's speculations were confirmed by more modern research. Freud also wrote a book about aphasia.

The origin of Freud's early work with psychoanalysis can be linked to Joseph Breuer. Freud credits Breuer with the discovery of the psychoanalytical method. The so-called ur-case of psychoanalysis was Breuer's case, Anna O. (Bertha Pappenheim). In 1880 Pappenheim came to Breuer with symptoms of what was then called female hysteria. She was a highly intelligent 21-year-old woman. She presented with symptoms such as paralysis of the limbs, split personality and amnesia; today these symptoms are known as conversion disorder. After many doctors had given up and accused Anna O. of faking her symptoms, Breuer decided to treat her sympathetically, which he did with all of his patients. He started to hear her mumble words during what he called states of absence. Eventually Breuer started to recognize some of the words and wrote them down. He then hypnotized her and repeated the words to her; Breuer found out that the words were associated with her father's illness and death. Her recounting of her problems she called "chimney sweeping," and became the basis of the "talking cure."

In the early 1890s Freud used a form of treatment based on the one that Breuer had described to him, modified by what he called his "pressure technique." The traditional story, based on Freud's later accounts of this period, is that as a result of his use of this procedure most of his patients in the mid-1890s reported early childhood sexual abuse. He believed these stories, but after having heard a patient tell the story about Freud's personal friend being the victimizer, Freud concluded that his patients were fantasizing the abuse scenes.

In 1896 Freud posited that the symptoms of 'hysteria' and obsessional neurosis derived from unconscious memories of sexual abuse in infancy, and claimed that he had uncovered such incidents for every single one of his current patients (one third of whom were men). However a close reading of his papers and letters from this period indicates that these patients did not report early childhood sexual abuse as he later claimed: rather, he based his claims on analytically inferring the supposed incidents, using a procedure that was heavily dependent on the symbolic interpretation of somatic symptoms.

Freud adjusted his technique to one of bringing unconscious thoughts and feelings to consciousness by encouraging the patient to talk in free association and to talk about dreams. There is a relative lack of direct engagement on the part of the analyst, which is meant to encourage the patient to project thoughts and feelings onto the analyst. Through this process, transference, the patient can reenact and resolve repressed conflicts, especially childhood conflicts with (or about) parents.

Freud and cocaine

Freud was an early user and proponent of cocaine as a stimulant as well as analgesic. He wrote several articles on the antidepressant qualities of the drug and he was influenced by his friend and confidant Wilhelm Fliess, who recommended cocaine for the treatment of the "nasal reflex neurosis." Fliess operated on Freud and a number of Freud's patients whom he believed to be suffering from the disorder, including Emma Eckstein, whose surgery proved disastrous as he left a wad of gauze in her nose which became infected. Freud, in deference to his friend, defended Fliess's diagnosis of hysteria as the cause of her complaints.

Freud felt that cocaine would work as a panacea for many disorders and wrote a well-received paper, "On Coca," expounding on its virtues. He prescribed it to his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow to help him overcome a morphine addiction he had acquired while treating a disease of the nervous system. Freud also recommended it to many of his close family and friends. He narrowly missed out on obtaining scientific priority for discovering cocaine's anesthetic properties (of which Freud was aware but on which he had not written extensively), after Karl Koller, a colleague of Freud's in Vienna, presented a report to a medical society in 1884 outlining the ways in which cocaine could be used for delicate eye surgery. Freud was bruised by this, especially because this would turn out to be one of the few safe uses of cocaine, as reports of addiction and overdose began to filter in from many places in the world. Freud's medical reputation became somewhat tarnished because of this early ambition. Furthermore, Freud's friend Fleischl-Marxow developed an acute case of "cocaine psychosis" as a result of Freud's prescriptions and died a few years later. Freud felt great regret over these events, which later biographers have dubbed "The Cocaine Incident."

The unconscious

Freud's most enduring contribution to Western thought was his theory of the unconscious mind. During the nineteenth century, the dominant trend in Western thought was positivism, which subscribed to the belief that people could ascertain real knowledge concerning themselves and their environment and judiciously exercise control over both. Freud did not create the idea of the unconscious. It has ancient roots and was explored by authors, from William Shakespeare [11] [12][13][14] to nineteenth century Gothic fiction in such works as Robert Louis Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Western philosophers, such as Spinoza, Leibniz, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche, developed a western view of mind which also foreshadowed Freud's. Freud drew on his own Jewish roots to develop an interpersonal examination of the unconscious mind[15] [16] as well as his own therapeutic roots in hypnosis into an apparently new therapeutic intervention and its associated rationale.

Finally, medical science during the latter half of the nineteenth century had recently discovered aspects of the autonomous nervous system that appeared "unconscious," that is, beyond consciousness. Psychologist Jacques Van Rillaer, among others, pointed out, "contrary to what most people believe, the unconscious was not discovered by Freud. In 1890, when psychoanalysis was still unheard of, William James, in his monumental treatise on psychology, examined the way Schopenhauer, von Hartmann, Janet, Binet and others had used the term 'unconscious' and 'subconscious'. Boris Sidis, a Jewish Russian who escaped to the United States of America in 1887, and studied under William James, wrote The Psychology of Suggestion: A Research into the Subconscious Nature of Man and Society in 1898, followed by ten or more works over the next 25 years on similar topics to the works of Freud.

The historian of psychology Mark Altschule wrote: "It is difficult—or perhaps impossible—to find a nineteenth-century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognize unconscious cerebration as not only real but of the highest importance."[17]

Freud's contribution was to give the unconscious a content, a repressive function that would run counter to the positivism of his era, suggesting that free will is a delusion and that we are not entirely aware of what we think and often act for reasons that have little to do with our conscious thoughts. This proved a fertile area for the imaginative mind of Freud and his followers.

Dreams, which he called the "royal road to the unconscious," provided the best access to our unconscious life and the best illustration of its "logic," which was different from the logic of conscious thought. Freud developed his first topology of the psyche in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) in which he proposed the argument that the unconscious exists and described a method for gaining access to it. The preconscious was described as a layer between conscious and unconscious thought—that which we could access with a little effort. Thus for Freud, the ideals of the Enlightenment, positivism and rationalism, could be achieved through understanding, transforming, and mastering the unconscious, rather than through denying or repressing it.

Crucial to the operation of the unconscious is "repression." According to Freud, people often experience thoughts and feelings that are so painful that they cannot bear them. Such thoughts and feelings—and associated memories—could not, Freud argued, be banished from the mind, but could be banished from consciousness. Thus they come to constitute the unconscious. Although Freud later attempted to find patterns of repression among his patients in order to derive a general model of the mind, he also observed that individual patients repress different things. Moreover, Freud observed that the process of repression is itself a non-conscious act (in other words, it did not occur through people willing away certain thoughts or feelings). Freud supposed that what people repressed was in part determined by their unconscious. In other words, the unconscious was for Freud both a cause and effect of repression.

Later, Freud distinguished between three concepts of the unconscious: the descriptive unconscious, the dynamic unconscious, and the system unconscious. The descriptive unconscious referred to all those features of mental life of which people are not subjectively aware. The dynamic unconscious, a more specific construct, referred to mental processes and contents which are defensively removed from consciousness as a result of conflicting attitudes. The system unconscious denoted the idea that when mental processes are repressed, they become organized by principles different from those of the conscious mind, such as condensation and displacement.

Eventually, Freud abandoned the idea of the system unconscious, replacing it with the concept of the Ego, superego, and id. Throughout his career, however, he retained the descriptive and dynamic conceptions of the unconscious.

Psychosexual development

Freud hoped to prove that his model was universally valid and thus turned back to ancient mythology and contemporary ethnography for comparative material as well as creating a structural model of the mind which was supposed to describe the struggle of every child. Freud named his new theory the Oedipus complex after the famous Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex by Sophocles.

"I found in myself a constant love for my mother, and jealousy of my father. I now consider this to be a universal event in childhood,"

Freud said. Freud sought to anchor this pattern of development in the dynamics of the mind. Each stage is a progression into adult sexual maturity, characterized by a strong ego and the ability to delay gratification (cf. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality). He used the Oedipus conflict to point out how much he believed that people desire incest and must repress that desire. The Oedipus conflict was described as a state of psychosexual development and awareness. He also turned to anthropological studies of totemism and argued that totemism reflected a ritualized enactment of a tribal Oedipal conflict.

Freud originally posited childhood sexual abuse as a general explanation for the origin of neuroses, but he abandoned this so-called "seduction theory" as insufficiently explanatory, noting that he had found many cases in which apparent memories of childhood sexual abuse were based more on imagination (derived, and some would say suggested, under hypnosis) than on real events. During the late 1890s Freud, who never abandoned his belief in the sexual etiology of neuroses, began to emphasize fantasies built around the Oedipus complex as the primary cause of hysteria and other neurotic symptoms. Despite this change in his explanatory model, Freud always recognized that some neurotics had been sexually abused by their fathers, and was quite explicit about discussing several patients whom he knew to have been abused.[18]

Freud also believed that the libido developed in individuals by changing its object, a process codified by the concept of sublimation. He argued that humans are born "polymorphously perverse," meaning that any number of objects could be a source of pleasure. As humans develop, they become fixated on different and specific objects through stages of development—first in the oral stage (exemplified by an infant's pleasure in nursing), then in the anal stage (exemplified by a toddler's pleasure in evacuating his or her bowels), then in the phallic stage, arriving at the goal of mature sexuality. Freud argued that children then passed through a stage in which they fixated on the mother as a sexual object (known as the Oedipus Complex) but that the child eventually overcame and repressed this desire because of its taboo nature. (The lesser known Electra complex refers to such a fixation on the father.) The repressive or dormant latency stage of psychosexual development preceded the sexually mature genital stage of psychosexual development. The difficulty of ever really giving up the desire for the mother versus the demands of the civilization to give up that desire characterizes the etiology of psychological illness in Freud's Oedipal model.

Freud's way of interpretation has been called phallocentric by many contemporary thinkers. This is because, for Freud, the unconscious always desires the phallus (penis). Males are afraid of castration–losing their phallus or masculinity to another male. Females always desire to have a phallus–an unfulfillable desire. Thus boys resent their fathers (fear of castration) and girls desire theirs. For Freud, desire is always defined in the negative term of lack; you always desire what you don't have or what you are not, and it is very unlikely that you will fulfill this desire. Thus his psychoanalysis treatment is meant to teach the patient to cope with his or her insatiable desires.

Ego, super-ego, and id

The Oedipal model, otherwise known as the topographical model, created a struggle between the repressed material of the unconscious and the conscious ego. In his later work, and under the pressure of a number of his former proteges splitting off and developing their own theories that addressed the problems of the ego, Freud proposed that the psyche could be divided into three parts: Ego, super-ego, and id. Freud discussed this structural model of the mind in the 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and fully elaborated it in The Ego and the Id (1923), where he developed it as an alternative to his previous topographic schema (conscious, unconscious, preconscious).

Freud acknowledged that his use of the term Id (or the It) derives from the writings of Georg Grodeck. The term Id appears in the earliest writing of Boris Sidis, attributed to William James, as early as 1898. In creating the structural model, Freud recognized that the "superego" function, which derived from the parent and the demands of civilization, could also be unconscious. In response to his disciples turned adversaries, he located an unconscious within the ego. This was a theoretical answer to their attack on the predominant focus on the unconscious, but it came at the cost of revising his whole theory.

The life and death instincts

In his later theory Freud argued that humans were driven by two conflicting central desires: the life drive (Eros) (incorporating the sex drive) and the death drive (Thanatos). Freud's description of Eros, whose energy is known as libido, included all creative, life-producing drives. The death drive (or death instinct), whose energy is known as mortido, represented an urge inherent in all living things to return to a state of calm: in other words, an inorganic or dead state. He recognized Thanatos only in his later years, developing his theory on the death drive in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Freud approached the paradox between the life drives and the death drives by defining pleasure and unpleasure. According to Freud, unpleasure refers to stimulus that the body receives. (For example, excessive friction on the skin's surface produces a burning sensation; or, the bombardment of visual stimuli amidst rush hour traffic produces anxiety.) Conversely, pleasure is a result of a decrease in stimuli (for example, a calm environment the body enters after having been subjected to a hectic environment). If pleasure increases as stimuli decreases, then the ultimate experience of pleasure for Freud would be zero stimulus, or death. Given this proposition, Freud acknowledges the tendency for the unconscious to repeat unpleasurable experiences in order to desensitize, or deaden, the body. This compulsion to repeat unpleasurable experiences explains why traumatic nightmares occur in dreams, as nightmares seem to contradict Freud's earlier conception of dreams purely as a site of pleasure, fantasy, and desire. On the one hand, the life drives promote survival by avoiding extreme unpleasure and any threat to life. On the other hand, the death drive functions simultaneously toward extreme pleasure, which leads to death. Freud addresses the conceptual dualities of pleasure and unpleasure, as well as sex/life and death, in his discussions on masochism and sadomasochism. The tension between Eros and Thanatos represents a revolution in his manner of thinking. Some also refer to the death instinct as the Nirvana Principle.

These ideas owe a great deal to the later influence of both Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche. Schopenhauer's pessimistic philosophy, expounded in The World as Will and Representation, describes a renunciation of the will to live that corresponds on many levels with Freud's Death Drive. The life drive clearly owes much to Nietzsche's concept of the Dionysian in The Birth of Tragedy. Freud was an avid reader of both philosophers and acknowledged their influence. Some have speculated that this new theory also owed something to World War I, in which Freud lost a son.

Legacy

Psychotherapy

Freud's theories and research methods were controversial during his life and still are so today, but few dispute his huge impact on the development of psychotherapy.

Most importantly, Freud popularized the "talking-cure"(which actually derived from "Anna O.," a patient of one of Freud's mentors, Joseph Breuer— an idea that a person could solve problems simply by talking over them. Even though many psychotherapists today tend to reject the specifics of Freud's theories, this basic mode of treatment comes largely from his work.

Most of Freud's specific theories—like his stages of psychosexual development—and especially his methodology, have fallen out of favor in modern cognitive and experimental psychology.

Some psychotherapists, however, still follow an approximately Freudian system of treatment. Many more have modified his approach, or joined one of the schools that branched from his original theories, such as the Neo-Freudians. Still others reject his theories entirely, although their practice may still reflect his influence.

Psychoanalysis today maintains the same ambivalent relationship with medicine and academia that Freud experienced during his life.

Philosophy

While he saw himself as a scientist, Freud greatly admired Theodor Lipps, a philosopher and main supporter of the ideas of the subconscious and empathy.[19] Freud's theories have had a tremendous impact on the humanities—especially on the Frankfurt school and critical theory—where they are more widely studied today than in the field of psychology. Freud's model of the mind is often criticized as an unsubstantiated challenge to the enlightenment model of rational agency, which was a key element of much modern philosophy.

- Rationality. While many enlightenment thinkers viewed rationality as both an unproblematic ideal and a defining feature of man, Freud's model of the mind drastically reduced the scope and power of reason. In Freud's view, reasoning occurs in the conscious mind—the ego—but this is only a small part of the whole. The mind also contains the hidden, irrational elements of id and superego, which lie outside of conscious control, drive behavior, and motivate conscious activities. As a result, these structures call into question humans' ability to act purely on the basis of reason, since lurking motives are also always at play. Moreover, this model of the mind makes rationality itself suspect, since it may be motivated by hidden urges or societal forces (e.g. defense mechanisms, where reasoning becomes "rationalizing").

- Transparency of Self. Another common assumption in pre-Freudian philosophy was that people have immediate and unproblematic access to themselves. Emblematic of this position is René Descartes' famous dictum, "Cogito ergo sum" ("I think, therefore I am"). For Freud, however, many central aspects of a person remain radically inaccessible to the conscious mind (without the aid of psychotherapy), which undermines the once unquestionable status of first-person knowledge.

Critical reactions

It is part of the mythology of psychoanalysis that Freud was a lone scientist fighting the prejudice of Victorian society with his radically new understanding of childhood sexuality. Like most myths, this version is based on some truth but highly embellished. Krafft-Ebing, among others, had discussed such cases in his Psychopathia Sexualis. Although Freud's theories became influential, they came under widespread criticism during his lifetime and especially quite recently. A paper by Lydiard H. Horton, read in 1915 at a joint meeting of the American Psychological Association and the New York Academy of Sciences, called Freud's dream theory "dangerously inaccurate" and noted that "rank confabulations...appear to hold water, psycho analytically." The philosopher A. C. Grayling has said that "Philosophies that capture the imagination never wholly fade....But as to Freud's claims upon truth, the judgment of time seems to be running against him."[20] Peter D. Kramer, a psychiatrist and faculty member of Brown Medical School, said "I'm afraid [Freud] doesn't hold up very well at all. It almost feels like a personal betrayal to say that. But every particular is wrong: the universality of the Oedipus complex, penis envy, infantile sexuality."

He has been called "history's most debunked doctor."[21] Since the mid-1990s, there has been a critical reassessment of Freud. Until the past 20 years, much of the history of psychoanalysis was written by analysts, who had little reason to be critical. Since then, there has been an outpouring of critical research.

According to Richard Webster, author of Why Freud Was Wrong (1995):

Freud made no substantial intellectual discoveries. He was the creator of a complex pseudo-science which should be recognized as one of the great follies of Western civilisation. In creating his particular pseudo-science, Freud developed an autocratic, anti-empirical intellectual style which has contributed immeasurably to the intellectual ills of our own era. His original theoretical system, his habits of thought and his entire attitude to scientific research are so far removed from any responsible method of inquiry that no intellectual approach basing itself upon these is likely to endure.[22]

Other critics, like Frederick C. Crews, author of The Memory Wars: Freud's Legacy in Dispute (1995), are even more blunt:

He was a charlatan. In 1896 he published three papers on the ideology of hysteria claiming that he had cured X number of patients. First it was thirteen and then it was eighteen. And he had cured them all by presenting them, or rather by obliging them to remember, that they had been sexually abused as children. In 1897 he lost faith in this theory, but he'd told his colleagues that this was the way to cure hysteria. So he had a scientific obligation to tell people about his change of mind. But he didn't. He didn't even hint at it until 1905, and even then he wasn't clear. Meanwhile, where were the thirteen patients? Where were the eighteen patients? You read the Freud - Fleiss letters and you find that Freud's patients were leaving at the time. By 1897 he didn't have any patients worth mentioning, and he hadn't cured any of them, and he knew it perfectly well. Well, if a scientist did that today, of course he would be stripped of his job. He would be stripped of his research funds. He would be disgraced for life. But Freud was so brilliant at controlling his own legend that people can hear charges like this, and even admit that they're true, and yet not have their faith in the system of thought affected in any way.[23]

Feminist critiques

Freud was an early champion of both sexual freedom and education for women (Freud, "Civilized Sexual Morality and Modern Nervousness"). Some feminists, however, have argued that at worst his views of women's sexual development set the progress of women in Western culture back decades, and that at best they lent themselves to the ideology of female inferiority.

Believing as he did that women are a kind of mutilated male, who must learn to accept their "deformity" (the "lack" of a penis) and submit to some imagined biological imperative, he contributed to the vocabulary of misogyny.

Terms such as "penis envy" and "castration anxiety" contributed to discouraging women from entering any field dominated by men, until the 1970s. Some of Freud's most criticized statements appear in his 'Fragment of Analysis' on Ida Bauer such as "This was surely just the situation to call up distinct feelings of sexual excitement in a girl of fourteen" in reference to Dora being kissed by a 'young man of prepossessing appearance'[24] implying the passivity of female sexuality and his statement "I should without question consider a person hysterical in whom an occasion for sexual excitement elicited feelings that were preponderantly or exclusively unpleasurable"[24]

On the other hand, feminist theorists such as Juliet Mitchell, Nancy Chodorow, Jessica Benjamin, Jane Gallop, and Jane Flax have argued that psychoanalytic theory is essentially related to the feminist project and must, like other theoretical traditions, be adapted by women to free it from vestiges of sexism. Freud's views are still being questioned by people concerned about women's equality. Another feminist who finds potential use of Freud's theories in the feminist movement is Shulamith Firestone. In "Freudianism: The Misguided Feminism," she discusses how Freudianism is essentially completely accurate, with the exception of one crucial detail: everywhere that Freud wrote "penis," the word should be replaced with "power."

Critiques of scientific validity

(For a lengthier treatment, see the article on psychoanalysis.) Finally, Freud's theories are often criticized as not scientific.[25] This objection was raised most famously by Karl Popper, who claimed that all proper scientific theories must be potentially falsifiable. Popper argued that no experiment or observation could ever falsify Freud's theories of psychology (e.g. someone who denies having an Oedipal complex is interpreted as repressing it), and thus they could not be considered scientific.[26] Some proponents of science conclude that this standard invalidates Freudian theory as a means of interpreting and explaining human behavior. Others, like Adolf Grünbaum accept Popper's analysis, but do not reject Freud's theories out of hand.

Major works

- Studies on Hysteria (with Josef Breuer) (Studien über Hysterie, 1895)

- The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung, 1899 [1900])

- The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens, 1901)

- Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie, 1905)

- Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten, 1905)

- Totem and Taboo (Totem und Tabu, 1913)

- On Narcissism (Zur Einführung des Narzißmus, 1914)

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Jenseits des Lustprinzips, 1920)

- The Ego and the Id (Das Ich und das Es, 1923)

- The Future of an Illusion (Die Zukunft einer Illusion, 1927)

- Civilization and Its Discontents (Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, 1930)

- Moses and Monotheism (Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion, 1939)

- An Outline of Psycho-Analysis (Abriß der Psychoanalyse, 1940)

Biographies

The area of biography has been especially contentious in the historiography of psychoanalysis, for two primary reasons: first, following his death, significant portions of his personal papers were for several decades made available only at the permission of his biological and intellectual heirs (his daughter, Anna Freud, was extremely protective of her father's reputation); second, much of the data and theory of Freudian psychoanalysis hinges upon the personal testimony of Freud himself, and so to challenge Freud's legitimacy or honesty has been seen by many as an attack on the roots of his enduring work.

The first biographies of Freud were written by Freud himself: his On the History of the Psychoanalytic Movement (1914) and An Autobiographical Study (1924) provided much of the basis for discussions by later biographers, including "debunkers" (as they contain a number of prominent omissions and potential misrepresentations). A few of the major biographies on Freud to come out over the twentieth century were:

- Helen Walker Puner, Freud: His Life and His Mind (1947) — Puner's "facts" were often shaky at best but she was remarkably insightful with regard to Freud's unanalyzed relationship to his mother, Amalia.

- Ernest Jones, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, 3 vols. (1953–1958) — the first "authorized" biography of Freud, made by one of his former students with the authorization and assistance of Anna Freud, with the hope of "dispelling the myths" from earlier biographies. Though this is the most comprehensive biography of Freud, Jones has been accused of writing more of a hagiography than a history of Freud. Among his questionable assertions, Jones diagnosed his own analyst, Ferenczi, as "psychotic." In the same breath, Jones also maligned Otto Rank, Ferenczi's close friend and Jones's most important rival for leadership of the movement in the 1920s.

- Henri Ellenberger, The Discovery of the Unconscious (1970) — was the first book to, in a compelling way, attempt to situate Freud within the context of his time and intellectual thought, arguing that he was the intellectual heir of Franz Mesmer and that the genesis of his theory owed a large amount to the political context of turn of the nineteenth century Vienna.

- Frank Sulloway, Freud: Biologist of the Mind (1979) — Sulloway, one of the first professional/academic historians to write a biography of Freud, positioned Freud within the larger context of the history of science, arguing specifically that Freud was, in fact, a biologist in disguise (a "crypto-biologist," in Sulloway's terms), and sought to actively hide this.

- Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988) — Gay's impressively scholarly work was published in part as a response to the anti-Freudian literature and the "Freud Wars" of the 1980s (see below). Gay's book is probably the best pro-Freud biography available, though he is not completely uncritical of his hero. His "Bibliographical Essay" at the end of the volume provides astute evaluations of the voluminous literature on Freud up to the mid-1980s.

- Louis Breger, Freud: Darkness in the Midst of Vision (New York: Wiley, 2000). Though written from a psychoanalytic point of view (the author is a former President of the Institute of Contemporary Psychoanalysis), this is a "warts and all" life of Sigmund Freud. It corrects, in the light of historical research of recent decades, many (though not quite all) of several disputed traditional historical accounts of events uncritically recycled by Peter Gay.

The creation of Freud biographies has itself even been written about at some length—see, for example, Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, "A History of Freud Biographies," in Discovering the History of Psychiatry, edited by Mark S. Micale and Roy Porter (Oxford University Press, 1994).

Notes

- ↑ Moshe Gresser, Dual Allegiance: Freud As a Modern Jew (SUNY Press, 1994, ISBN 0791418111), 225.

- ↑ Der Analytiker und sein Phallusfisch Expertensprechen zum Thema Aale. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 S. Calvin Hall, A Primer in Freudian Psychology (Meridian Book, 1954, ISBN 0452011833).

- ↑ John Bowlby, Attachment and Loss: Vol I (Basic Books, 1999, ISBN 0465005438), 13-23.

- ↑ Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1988), 65-66.

- ↑ Ralph Blumenthal, Hotel log hints at desire that Freud didn't repress International Herald Tribune, December 24, 2006. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gerald Corey, Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy (Wadsworth Publishing, 2001, ISBN 0534348238), 67.

- ↑ The Life of Sigmund Freud (WGBH Educational Foundation, 2004). PBS.org. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ Peter Gay, "The TIME 100: Sigmund Freud.". Time Inc. March 29, 1999. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988).

- ↑ The Design Within: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Shakespeare, Edited by M. D. Faber. (New York, NY: Science House, 1970) An anthology of 33 papers on Shakespearean plays by psychoanalysts and literary critics whose work has been influenced by psychoanalysis.

- ↑ Daniel Meyer-Dinkgräfe, "Hamlet’s Procrastination: A Parallel to the Bhagavad-Gita," in Hamlet East West, edited by Marta Gibinska and Jerzy Limon. (Gdansk: Theatrum Gedanese Foundation, 1998), 187-195

- ↑ Daniel Meyer-Dinkgräfe. Consciousness and the Actor: A Reassessment of Western and Indian Approaches to the Actor's Emotional Involvement from the Perspective of Vedic Psychology Series 30: Theatre, Film and Television, Vol. 67 (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1996).

- ↑ Ralph Yarrow, "'Identity and Consciousness East and West: the case of Russell Hoban." Journal of Literature & Aesthetics 5 (2) (July-Dec. 1997): 19-26

- ↑ Sanford L. Drob, "This is Gold": Freud, Psychotherapy and the Lurianic Kabbalah. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ Sanford L. Drob, Jung and the Kabbalah History of Psychology 2(2) (May, 1999):102-118. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ Mark Altschule, Origins of Concepts in Human Behavior (New York: Wiley, 1977), 199.

- ↑ Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time, 95.

- ↑ G.W. Pigman, Freud and the history of empathy The International journal of psycho-analysis 76(2) (1995): 237-256. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ Scientist or storyteller? The Guardian, June 22, 2002. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ↑ Jerry Adler, Freud in our Midst Newsweek, March 27, 2006. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ Frederick Crews and Richard Webster, Freud and the Judaeo-Christian tradition The Times Literary Supplement, May 23, 1997. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ Harry Kreisler, Frederick Crews Interview Institute of International Studies, UC Berkeley, 1999. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 S.E. 7, 28.

- ↑ Emil Ludwig. 1973. Doctor Freud. (New York: Manor Books), 93

- ↑ Karl Popper, “Philosophy of Science: A Personal Report,” in British Philosophy in the Mid-Century: A Cambridge Symposium, ed. C. A. Mace (1957), 155-191; reprinted in Karl Popper. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (1963; 2d ed., 1965), 33-65.

Bibliography

- Altschule, Mark. Origins of Concepts in Human Behavior. New York: Wiley, 1977.

- Bowlby, John. Attachment and Loss: Vol I. Basic Books, 1999. ISBN 0465005438.

- Faber, Melvin D. (ed.). The Design Within: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Shakespeare. New York, NY: Science House, 1970. ISBN 978-0876680247.

- Micale, Mark S., and Roy Porter (eds.). Discovering the History of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0195077391.

- Popper, Karl. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0415285940.

Books about Freud and Psychoanalysis

- Andreas-Salome, Lou, The Freud Journal. Texas Bookman, 1996. ISBN 0704300222

- Bateman, Anthony and Jeremy Holmes, Introduction to Psychoanalysis: Contemporary Theory & Practice. London: Routledge, 1995. ISBN 978-0415107396.

- Bettelheim, Bruno. Freud and Man's Soul: An Important Re-Interpretation of Freudian Theory. New York: Vintage edition, 1983. ISBN 0394710363.

- Breger, Louis. Freud: Darkness in the Midst of Vision. Wiley, 2001. ISBN 978-0471078586.

- Corey, Gerald, Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy, 6th ed. 2000. ISBN 0534348238

- Farrell, John. Freud's Paranoid Quest: Psychoanalysis and Modern Suspicion NYU Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0814726495.

- Green, André. The Work of the Negative, Andrew Weller, Translator, Free Association Books, 1999. ISBN 1853434701

- Green, André. On Private Madness. International Universities Press, 1997. ISBN 0823638537

- Green, André. The Chains of Eros. Karnac Books, 2002. ISBN 1855759608

- Green, André. Psychoanalysis: A Paradigm For Clinical Thinking. Free Association Books, 2005. ISBN 1853437735

- Gresser, Moshe. Dual Allegiance: Freud As a Modern Jew. SUNY Press, 1994. ISBN 0791418111.

- Hall, S. Calvin. A Primer in Freudian Psychology. Meridian Book, 1954. ISBN 0452011833.

- Isbister, J. N. Freud, An Introduction to his Life and Work. Polity Press, 1985. ISBN 074560014X.

- Jones, Ernest, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud. Basic Books, 1981. ISBN 0465040152

- Laplanche, Jean, and J.B. Pontalis, The Language of Psycho-Analysis. W. W. Norton & Company, 1974. ISBN 0393011054

- Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff. The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory. Ballantine Books, 2003. ISBN 0345452798.

- Paskauskas, R. Andrew. (ed.). The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones, 1908-1939. Belknap Press; Reprint edition 1995. ISBN 067415424X.

- Puner, Helen Walker. Freud: His Life and His Mind. Transaction Publishers; Revised edition, 1992. ISBN 978-1560006114.

- Rieff, Philip. Freud: The Mind of the Moralist. 3d ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1979. ISBN 0226716392.

- Robert, Marthe. The Psychoanalytic Revolution. Allen & Unwin, 1966. ISBN 978-0041310177.

- Spielrein, Sabina. Destruction as cause of becoming. 1993. ASIN B0006RF20A

- Sulloway, Frank. Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend. Harvard University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0674323353.

- Young-Bruehl, Elisabeth. Freud on Women: A Reader. Norton, 1992. ISBN 0393308707.

Conceptual critiques

- Aziz, Robert, The Syndetic Paradigm:The Untrodden Path Beyond Freud and Jung. The State University of New York Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0791469828.

- Adler, Mortimer J., What Man Has Made of Man: A Study of the Consequences of Platonism and Positivism in Psychology. (1937) Dyer Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1406775785.

- Chasseguet-Smirgel, Janine, & Béla Grunberger. Freud or Reich? Psychoanalysis and Illusion. London: Free Association Books, 1986. ISBN 978-0946960323.

- Cioffi, Frank. Freud and the Question of Pseudoscience. Chicago and La Salle: Open Court, 1999. ISBN 978-0812693850.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari., Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane. University of Minnesota Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0816612253.

- Ellenberger, Henri. The Discovery of the Unconscious: the History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. Basic Books, 1970. ISBN 978-0465016723.

- Eysenck, H. J. and G. D. Wilson. The Experimental Study of Freudian Theories. London: Methuen, 1973. ISBN 978-0416780109.

- Hobson, J. Allan, Dreaming: An Introduction to the Science of Sleep. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0192804820.

- Johnston, Thomas. Freud and Political Thought. New York: Citadel, 1965. ISBN 978-1199098894.

- Kofman, Sarah. The Enigma of Woman: Woman in Freud's Writings. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985. ISBN 0801498988.

- Marcuse, Herbert. Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1974. ISBN 978-0807015551.

- Mitchell, Juliet. Psychoanalysis and Feminism: A Radical Reassessment of Freudian Psychoanalysis. (1974) Basic Books reissue 2000. ISBN 0465046088.

- Neu, Jerome (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Freud. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521377799.

- Ricoeur, Paul. Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation, trans. Denis Savage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0300021899.

- Ricoeur, Paul. The Conflict of Interpretations: Essays in Hermeneutics, ed. Don Ihde, Northwestern University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0810123977.

- Roazen, Paul. Freud and His Followers. Da Capo, 1992. ISBN 978-0306804724.

- Szasz, Thomas. Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus's Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry. Syracuse University Press, 1990. ISBN 0815602472.

- Torrey, E. Fuller. Freudian Fraud: The Malignant Effect of Freud's Theory on American Thought and Culture. Lucas Publishers, 1999. ISBN 978-1929636006.

- Voloshinov, Valentin. Freudianism: A Marxist critique. Academic Press, 1976. ISBN 0127232508.

- Wollheim, Richard, Freud, 2nd ed. London: Fontana, 1991. ISBN 978-0006862239.

Biographical critiques

- Bakan, David. Sigmund Freud and the Jewish Mystical Tradition. (1958) reprint ed. New York: Dover Publications, 2004. ISBN 0486437671.

- Crews, Frederick. Unauthorized Freud: doubters confront a legend. New York: Viking, 1998. ISBN 0670872210.

- Crews, Frederick. The Memory Wars: Freud's Legacy in Dispute. New York Review of Books, 1995. ISBN 978-0940322042.

- Dolnick, Edward. Madness on the Couch: Blaming the Victim in the Heyday of Psychoanalysis. Simon & Shuster, 1998. ISBN 0684824973.

- Dufresne, T. Killing Freud: Twentieth-Century Culture And the Death of Psychoanalysis. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006. ISBN 978-0826493392.

- Esterson, Allen. Seductive Mirage: An Exploration of the Work of Sigmund Freud. Chicago, IL: Open Court, 1998. ISBN 978-0812692310.

- Eysenck, H. J. The Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire. Viking, 1985. ISBN 0670801305.

- Jurjevich, R. M. The Hoax of Freudism: A study of Brainwashing the American Professionals and Laymen. Dorrance, 1974. ISBN 0805918566.

- LaPiere, R. T. The Freudian Ethic: An Analysis of the Subversion of Western Character. Greenwood Press, 1974. ISBN 0837175437.

- Lear, Jonathan. Freud. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0415314518.

- Ludwig, Emil. Doctor Freud. New York: Manor Books, 1973. ASIN B0007EBRV0

- MacDonald, Kevin B. The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements. Authorhouse, 2002. ISBN 0759672229.

- Macmillan, Malcolm. Freud Evaluated: The Completed Arc. MIT Press, 1996. ISBN 0262631717.

- Scharnberg, Max. The non-authentic nature of Freud's observations. Almqvist & Wiksell International, 1993. ISBN 9155431224.

- Stannard, D. E. Shrinking History: On Freud and the Failure of Psychohistory. Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0195030443.

- Thornton, E. M. Freud and Cocaine: The Freudian Fallacy. London: Blond & Briggs, 1983. ISBN 0856341398.

- Webster, Richard. Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science, and Psychoanalysis. BasicBooks, 1995. ISBN 0465095798.

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Freud Museum, Maresfield Gardens, London

- Freud Museum, Berggasse 19, Vienna

- Sigmund Freud Life and Work

- Sigmund-Freud-Institut

- Freud Archives at Library of Congress

- Works by Sigmund Freud. Project Gutenberg

- Essays by Freud at Quotidiana.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.