| Galápagos Islands* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, viii, ix, x |

| Reference | 1 |

| Region** | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1978 (2nd Session) |

| Extensions | 2001 |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

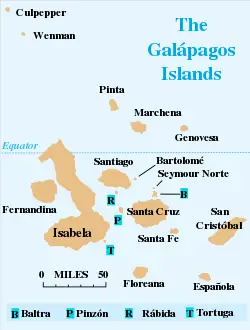

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish names: Islas de Colónumio or Islas Galápagos, from galápago, "saddle"- after the shells of saddlebacked Galápagos tortoises) are an archipelago made up of 13 main volcanic islands, six smaller islands, and 107 rocks and islets. The oldest island is thought to have formed between five and ten million years ago, a result of tectonic activity. The youngest islands, Isabela and Fernandina, are still being formed through volcanic eruption.

The Galápagos archipelago is part of Ecuador, a country in northwestern South America that claimed it in 1832.

The islands are distributed around the equator, about 600 miles (965 km) west of Ecuador. They were recently found to have three volcanoes in the center island, all of them active. The archipelago is famed for its great number of endemic species, especially of birds (28), reptiles (19), and fish, and for the studies by Charles Darwin that led to his theory of evolution by natural selection.

Main islands

The archipelago has been known by many different names, including the "Enchanted Islands" because of the way in which strong, swift currents made navigation difficult. The first crude navigation chart of the islands was done by the buccaneer Ambrose Cowley in 1684, and in those charts he named the islands after some of his fellow pirates or after the English noblemen who helped the pirates' cause. The term "Galápagos" refers to the Spanish name given to the giant land tortoises known to inhabit the islands.

The main islands of the archipelago (with their English names) shown alphabetically:

Baltra (South Seymour)

During World War II Baltra was established as a U.S. Air Force base. Crews stationed at Baltra patrolled the Pacific for enemy submarines as well as providing protection for the Panama Canal. After the war the facilities were given to the government of Ecuador. Today the island continues as an official Ecuadorian military base.

Until 1986, Baltra had the only airport serving the Galápagos. Now there are two airports, the other located on San Cristobal Island; most flights operating in and out of Galápagos still fly into Baltra.

During the 1930s scientists decided to move 70 of Baltra's Land Iguanas to the neighboring island of North Seymour as part of an experiment. This move had unexpected results, for during the WWII military occupation of Baltra, the native iguanas became extinct on the island. During the 1980s iguanas from North Seymour were brought to the Darwin Station as part of a breeding and repopulation project and in the 1990s land iguanas were reintroduced to Baltra.

Bartolomé

Named for Lt. David Bartholomew of the British Navy, this small island is located just east of Santiago. Desolate Bartolome is one of the most visited and photographed islands in the Galápagos.

Bartolomé is an extinct volcano and has a variety of variably colored volcanic formations, including a tuff cone known as Pinnacle Rock. This large black, partially eroded cone was created when lava reached the sea. Contact with seawater resulted in a phreatic explosion. The exploded molten fragments fused together, forming a welded tuff.

Bartolomé is inhabited by Galápagos Penguins, sea lions, nesting marine turtles, white-tipped reef sharks, and a variety of birds.

Darwin (Culpepper)

This island is named after Charles Darwin. It has an area of 1.1 square kilometers (0.4 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 168 metres (551 ft). Fur seals, frigates, marine iguanas, swallow-tailed gulls, sea lions, whales, marine turtles, dolphins, red-footed and Nazca boobies can be seen.

Darwin's Arch, a natural rock arch which would at one time have been part of this larger structure, is located less than a kilometer from the main Darwin Island on an irregularly shaped, rocky, submerged plateau, nicknamed "the theatre." It is a landmark well known to the island's few visitors. The arch collapsed into the sea on May 17, 2021 from natural erosion. The event was witnessed by divers aboard the Galapagos Aggressor III.[1]

Following the collapse of the arch, the remaining columns of rock have been nicknamed the "Pillars of Evolution" (Spanish: Los Pilares de la Evolución) by locals in the tourism and diving industry.[2]

Española (Hood)

This island's name was given in honor of Spain. It is also known as Hood after an English nobleman. It has an area of 60 square kilometers (23 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 206 meters (676 ft).

Española is the oldest island (at around 3.5 million years) and the southernmost in the chain. The island's remote location provides for a large number of endemic fauna. Secluded from the other islands, wildlife on Española adapted to the island's environment and natural resources. Marine iguanas on Española are the only ones that change color during breeding season.

The Waved Albatross is found on the island. The island's steep cliffs serve as the perfect runways for these large birds, which take off for their ocean feeding grounds near the mainland of Ecuador and Peru.

Española has two visitor sites. Gardner Bay is a swimming and snorkeling site as well as offering a beach. Punta Suarez has migrant, resident, and endemic wildlife including brightly colored Marine iguanas, Española Lava Lizards, Hood Mockingbirds, Swallow-tailed Gulls, Blue Footed Boobies and Nazca Boobies, Galápagos Hawks, a selection of Finch, and the Waved Albatross.

Fernandina (Narborough)

The name was given in honor of King Ferdinand of Spain, who sponsored the voyage of Columbus. Fernandina has an area of 642 square kilometers (248 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 1,494 meters (4,902 ft). This is the youngest and westernmost island. In May 13, 2005, a new very eruptive process began on this island when an ash and water vapor cloud rose to a height of 7 kilometers (4.4 mi) and lava flows descended the slopes of the volcano on the way to the sea.

Punta Espinosa is a narrow stretch of land where hundreds of marine iguanas gather, largely on black lava rocks. The famous Flightless Cormorant inhabits this island and also Galápagos Penguins, Pelicans and sea lions are abundant. Different types of lava flows can be compared and the mangrove forests can be observed.

Floreana (Charles or Santa María)

Originally named Charles Island for the British king Charles II, it was changed to Floreana after Juan José Flores, the first president of Ecuador, during whose administration the government of Ecuador took possession of the archipelago. It is also called Santa Maria after one of the caravels of Columbus. It has an area of 173 square kilometers (66.8 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 640 meters (2,100 ft).

It is one of the islands with the most interesting human history and was one of the earliest to be inhabited. General José Villamil established a colony for political prisoners here in 1832. At Post Office Bay, since the eighteenth century whalers kept a wooden barrel that served as post office so that mail could be picked up and delivered to their destinations, mainly Europe and the United States, by ships on their way home.

At the “Devil's Crown,” an underwater volcanic cone, coral formations are found. Pink flamingos and green sea turtles nest (December to May) on this island. The "patapegada" or Galápagos petrel is found here, a sea bird that spends most of its life away from land.

Genovesa Island (Tower)

The name is derived from Genoa, Italy where it is said Columbus was born. It has an area of 14 square kilometers (5.4 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 76 meters (249 ft). This island is formed by the remaining edge of a large crater that is submerged. Its nickname of “the bird island” is clearly justified. At Darwin Bay, frigatebirds, swallow-tailed gulls, the only nocturnal ones of its species in the world, can be seen. Red-footed boobies, noddy terns, lava gulls, tropic birds, doves, storm petrels and Darwin finches are also in sight. Prince Philip's Steps is a bird-watching plateau, with Nazca and red-footed boobies. There is a large Palo Santo forest.

Isabela (Albemarle)

This island was named in honor of Queen Isabela. With an area of 4,640 square kilometers (1,792 mi²), it is the largest island of the Galápagos. Its highest point is Wolf Volcano with an altitude of 1,707 meters (5,600 ft). The third-largest human settlement of the archipelago, Puerto Villamil, is located at the southeastern tip of the island.

The island's seahorse shape is the product of the merging of six large volcanoes into a single landmass. On this island Galápagos penguins, flightless cormorants, marine iguanas, boobies, pelicans, and Sally Lightfoot crabs abound. At the skirts and calderas of the volcanoes of Isabela, land iguanas and Galápagos tortoises can be observed, as well as Darwin finches, Galápagos hawks, Galápagos doves, and very interesting lowland vegetation.

Marchena (Bindloe)

Named after Fray Antonio Marchena, it has an area of 130 square kilometers (50 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 343 meters (1,125 ft). Galápagos hawks and sea lions inhabit this island, and it is home to the Marchena lava lizard, an endemic species.

North Seymour

Its name was given after an English nobleman called Lord Hugh Seymour. It has an area of 1.9 square kilometers (0.7 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 28 meters (92 ft). This island is home to a large population of blue-footed boobies and swallow-tailed gulls. It hosts one of the largest populations of frigate birds. It was formed from geological uplift.

Pinta (Abingdon)

Named for one of the caravels of Christopher Columbus, it has an area of 60 square kilometers (23 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 777 meters (2,549 ft). Swallow-tailed gulls, marine iguanas, sparrow hawks, and fur seals can be seen. It is also home to the world's rarest living creature, the Pinta giant tortoise. An aged male named Lonesome George is the only known survivor. Since there is little hope of finding another specimen, his species is doomed to extinction.

Pinzón (Duncan)

Named after the Pinzón brothers, captains of the Pinta and Niña caravels, it has an area of 18 square kilometers (7 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 458 meters (1,503 ft). Sea lions, Galápagos hawks, giant tortoises, marine iguanas, and dolphins can be seen here.

Rábida (Jervis)

This island bears the name of the convent of Rábida, where Columbus left his son during his voyage to the Americas. It has also been know as Jervis Island in honor of the eighteenth-century British admiral John Jervis.

It has an area of 4.9 square kilometers (1.9 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 367 meters (1,204 ft). The high amount of iron contained in the lava at Rábida give it a distinctive red color. White-Cheeked Pintail Ducks live in a salt-water lagoon close to the beach, where brown pelicans and boobies have built their nests. Until recently, flamingos were also found in the salt-water lagoon, but they have since moved on to other islands, likely due to a lack of food on Rábida. Nine species of finches have been reported.

San Cristóbal (Chatham)

It bears the name of the patron saint of seafarers, "St. Christopher." Its English name was given after William Pitt, first Earl of Chatham. It has an area of 558 square kilometers (215 mi²) and its highest point rises to 730 meters (2395 ft). This islands hosts frigate birds, sea lions, giant tortoises, blue and red footed boobies, tropicbirds, marine iguanas, dolphins, and swallow-tailed gulls.

Its vegetation includes Calandrinia galapagos, Lecocarpus darwinii, and trees such as Lignum vitae. The largest freshwater lake in the archipelago, Laguna El Junco, is located in the highlands of San Cristóbal. The capital of the province of Galápagos, Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, lies at the southern tip of the island.

Santa Cruz (Indefatigable)

Given the name of the Holy Cross in Spanish, its English name derives from the British vessel HMS Indefatigable. It has an area of 986 square kilometers (381 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 864 meters (2834 ft). Santa Cruz is the island that hosts the largest human population in the archipelago, at the town of Puerto Ayora. The Charles Darwin Research Station and the headquarters of the Galápagos National Park Service are located here.

The GNPS and CDRS operate a tortoise breeding center here, where young tortoises are hatched, reared, and prepared to be reintroduced to their natural habitat. The highlands offer exuberant vegetation and are famous for lava tunnels. Large tortoise populations are found here. Black Turtle Cove is a site surrounded by mangrove which sea turtles, rays and small sharks sometimes use as a mating area. Cerro Dragón, known for its flamingo lagoon, is also located here, and along the trail one may see land iguanas foraging.

Santa Fe (Barrington)

Named after a city in Spain, it has an area of 24 square kilometers (9 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 259 meters (850 ft). Santa Fe hosts a forest of Opuntia cactus, which are the largest of the archipelago, and Palo Santo. Weathered cliffs provide a haven for swallow-tailed gulls, red-billed tropic birds, and shear-waters petrels. Santa Fe species of land iguanas are often seen, as well as lava lizards.

Santiago (San Salvador, James)

Its name is equivalent to Saint James in English; it is also known as San Salvador, after the first island discovered by Columbus in the Caribbean Sea. This island has an area of 585 square kilometers (226 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 907 meters (2976 ft). Marine iguanas, sea lions, fur seals, land and sea turtles, flamingos, dolphins, and sharks are found here.

Pigs and goats, which were introduced by humans to the islands and caused great harm to the endemic species, have been eradicated (pigs in 2002; goat eradication is nearing finalization). Darwin Finches and Galápagos Hawks are usually seen, as well as a colony of Fur Seals. At Sullivan Bay a recent (around 100 years ago) pahoehoe lava flow can be observed.

South Plaza

It is named in honor of a former president of Ecuador, General Leonidas Plaza. It has an area of 0.13 square kilometers (0.05 mi²) and a maximum altitude of 23 meters (75 ft). The flora of South Plaza includes Opuntia cactus and Sesuvium plants, which forms a reddish carpet on top of the lava formations. Iguanas (land and marine and some hybrids of both species) are abundant, and there are a large number of birds that can be observed from the cliffs at the southern part of the island, including tropic birds and swallow-tailed gulls.

Wolf (Wenman)

This island was named after the German geologist Theodor Wolf. It has an area of 1.3 square kilometers (0.5 mi²)and a maximum altitude of 253 meters (830 ft). Here fur seals, frigates, masked and red footed boobies, marine iguanas, sharks, whales, dolphins, and swallow-tailed gulls can be seen. The most famous resident is the vampire finch, which feeds on the blood of the boobies and is only found on this island.

History

European discovery of the Galápagos Islands occurred when Dominican Fray Tomás de Berlanga, the fourth bishop of Panama, sailed to Peru to settle a dispute between Francisco Pizarro and his lieutenants. De Berlanga's vessel drifted off course when the winds diminished, and his party reached the islands on March 10, 1535. According to a 1956 study by Thor Heyerdahl and Arne Skjølsvold, remains of potsherds and other artifacts from several sites on the islands suggest visitation by South American peoples prior to the arrival of the Spanish.

The islands first appeared on maps about 1570 in those drawn by Abraham Ortelius and Mercator. The islands were called "Insulae de los Galopegos" (Islands of the Tortoises).

The first English captain to visit the Galápagos Islands was Richard Hawkins, in 1593. Until the early nineteenth century, the archipelago was often used as a hideout by mostly English pirates who pilfered Spanish galleons carrying gold and silver from South America to Spain.

Alexander Selkirk, whose adventures in the Juan Fernández Islands inspired Daniel Defoe to write his novel Robinson Crusoe, visited the Galápagos in 1708 after he was picked up from Juan Fernández by the privateer Woodes Rogers. Rogers was refitting his ships in the islands after sacking Guayaquil.

The first scientific mission to the Galápagos arrived in 1790 under the leadership of Alessandro Malaspina, a Sicilian captain whose expedition was sponsored by the king of Spain. However, the records of the expedition were lost.

In 1793, James Colnett made a description of the flora and fauna of Galápagos and suggested that the islands could be used as a base for the whalers operating in the Pacific Ocean. He also drew the first accurate navigation charts of the islands. Whalers killed and captured thousands of the Galápagos tortoises to extract their fat. The tortoises could also be kept on board ship as a means of providing of fresh protein, as these animals could survive for several months without any food or water. The hunting of the tortoises was responsible for greatly diminishing, and in some cases eliminating, certain species. Along with whalers came the fur-seal hunters, who brought the population of this animal close to extinction.

Ecuador annexed the Galápagos Islands on February 12, 1832, naming it Archipelago of Ecuador. This was a new name that added to several names that had been, and are still, used to refer to the archipelago. The first governor of Galápagos, General José de Villamil, brought a group of convicts to populate the island of Floreana and in October 1832 some artisans and farmers joined them.

The survey ship HMS Beagle under Captain Robert FitzRoy arrived at the Galápagos on September 15, 1835, to survey harbor approaches. The captain and others on board, including the young naturalist Charles Darwin, made a scientific study of geology and biology on four of the thirteen islands before they left on October 20 to continue their round-the-world expedition. Darwin noticed that mockingbirds differed between islands, and the governor of the prison colony on Charles Island told him that tortoises differed from island to island as well.

Toward the end of the voyage Darwin speculated that these facts might "undermine the stability of Species."[3] When specimens of birds were analyzed on his return to England it was found that many apparently different kinds of birds were species of finches that were also unique to islands. These facts were crucial in Darwin's development of his theory of natural selection explaining evolution, which was presented in The Origin of Species.

José Valdizán and Manuel Julián Cobos tried a new colonization, beginning the exploitation of a type of lichen found in the islands (Roccella portentosa), used as a coloring agent. After the assassination of Valdizán by some of his workers, Cobos brought from the continent a group of more than a hundred workers to San Cristóbal Island and tried his luck at planting sugar cane. He ruled his plantation with an iron hand, which led to his assassination in 1904. Since 1897 Antonio Gil began another plantation on Isabela island.

In 1904, an expedition of the Academy of Sciences of California, led by Rollo Beck, stayed in the Galápagos collecting scientific material on geology, entomology, ornithology, botany, zoology, and herpetology. Another expedition from that Academy arrived in 1932 (Templeton Crocker Expedition) to collect insects, fish, shells, fossils, birds, and plants.

During World War II Ecuador authorized the United States to establish a naval base on Baltra island and radar stations in other strategic locations. In 1946 a penal colony was established on Isabela Island, but that was suspended in 1959.

Conservation

Though the first protective legislation for the Galápagos was enacted in 1934 and supplemented in 1936, it was not until the late 1950s that positive action was taken to control what was happening to the native flora and fauna. In 1955, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature organized a fact-finding mission to the Galápagos. Two years later, in 1957, UNESCO in cooperation with the government of Ecuador sent another expedition to study the conservation situation and choose a site for a research station.

In 1959, the centenary year of Charles Darwin's publication of The Origin of Species, the Ecuadorian government declared 97.5 percent of the archipelago's land area a national park, excepting areas already colonized. The Charles Darwin Foundation was founded the same year, with its international headquarters in Brussels. Its primary objectives are to ensure the conservation of unique Galápagos ecosystems and promote the scientific studies necessary to fulfill its conservation functions.

Conservation work began with the establishment of the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz Island in 1964. During the early years, conservation programs, such as eradication of introduced species and protection of native species, were carried out by station personnel. Currently, most resident scientists pursue conservation goals; most visiting scientists' work is oriented toward pure research.

When the national park was established, approximately 1,000 to 2,000 people called the islands their home. In 1972 a census was done in the archipelago and a population of 3,488 was recorded. By the 1980s, this number had dramatically risen to more than 15,000 people, and 2006 estimates place the population around 30,000 people.

In 1986 the surrounding 70,000 square kilometers (43,496 sq mi.) of ocean was declared a marine reserve, second only in size to Australia's Great Barrier Reef. In 1990 the archipelago became a whale sanctuary. In 1978 UNESCO recognized the islands as a World Heritage Site, and in 1985 a Biosphere Reserve. This was later extended in December 2001 to include the marine reserve.

Noteworthy species include:

- Galápagos land iguana, Conolophus subcristatus

- Marine iguana, Amblyrhynchus cristatus (only iguana feeding from the sea)

- Galápagos tortoise (Galápagos Giant tortoise), Geochelone elephantopus, known as Galápago in Spanish, it gave the name to the islands

- Blue-footed Booby Sula nebouxii

- Galápagos Green Turtle, thought to be a subspecies of the Pacific Green Turtle, Chelonia mydas agassisi

- Vampire Finch Geospiza difficilis septentrionalis, which is sometimes called the Sharp Beaked Ground Finch.

- Sea cucumber, the cause of environmental battles with fishermen over quotas of this expensive Asian delicacy Holothuria spp.

- four endemic species of mockingbirds, the first species Darwin noticed varying from island to island

- Thirteen endemic species of buntings, popularly called "Darwin's finches"

- Woodpecker Finch, Camarhynchus pallidus

- Galápagos Penguin, Spheniscus mendiculus, present because of the frigid Antarctic Humboldt Current

- Flightless Cormorant, Phalacrocorax harrisi

- Great Frigatebird and Magnificent Frigatebird

- Galápagos Hawk, Buteo galapagoensis

- Galápagos sea lions, Zalophus californianus, closely related to the California Sea Lion, but smaller

Environmental threats

Introduced plants and animals, such as feral goats, cats, and cattle, brought accidentally or willingly to the islands by humans, represent the main threat to Galápagos. Quick to reproduce, these alien species decimate the habitats of native species. The native animals, lacking natural predators on the islands, are defenseless to introduced species and fall prey.

Some of the most harmful introduced plants are the Guayaba or Guava Psidium guajava, avocado Persea americana, cascarilla Cinchona pubescens, balsa Ochroma pyramidale, blackberry Rubus glaucus, various citrus (orange, grapefruit, lemon), floripondio Datura arborea, higuerilla Ricinus communis and the elephant grass Pennisetum purpureum. These plants have invaded large areas and eliminated endemic species in the humid zones of San Cristobal, Floreana, Isabela, and Santa Cruz. Also, these harmful plants are just a few of introduced species on the Galapagos Islands. There are over 700 introduced plant species today. There are only 500 native and endemic species. This difference is creating a major problem for the islands and the natural species that inhabit them.

Many species were introduced to the Galápagos by pirates. Thor Heyerdahl quotes documents that mention that the Viceroy of Peru, knowing that British pirates ate the goats that they themselves had released in the islands, ordered dogs to be freed there to eliminate the goats. Also, when colonization of Floreana by José de Villamil failed, he ordered that the goats, donkeys, cows, and other animals from the farms in Floreana be transferred to other islands for the purpose of later colonization.

Non-native goats, pigs, dogs, rats, cats, mice, sheep, horses, donkeys, cows, poultry, ants, cockroaches, and some parasites inhabit the islands today. Dogs and cats attack the tame birds and destroy nests of birds, land tortoises, and marine turtles. They sometimes kill small Galápagos tortoises and iguanas. Pigs are even more harmful, covering larger areas and destroying the nests of tortoises, turtles and iguanas. Pigs also destroy vegetation in their search for roots and insects. This problem abounds in Cerro Azul volcano and Isabela, and in Santiago pigs may be the cause of the disappearance of the land iguanas that were so abundant when Darwin visited.

The black rat Rattus rattus attacks small Galápagos tortoises when they leave the nest, so that in Pinzón they stopped the reproduction for a period of more than 50 years; only adults were found on that island. Also, where the black rat is found, the endemic rat has disappeared. Cows and donkeys eat all the available vegetation and compete with native species for the scarce water. In 1959, fishermen introduced one male and two female goats to Pinta Island; by 1973 the National Park Service estimated the population of goats to be over 30,000 individuals. Goats were also introduced to Marchena in 1967 and Rabida in 1971.

The fast-growing poultry industry on the inhabited islands has been cause for concern from local conservationists, who fear that domestic birds could introduce disease into the endemic and wild bird populations.

The Galápagos marine sanctuary is under threat from a host of illegal fishing activities, in addition to other problems of development. The most pressing threat to the Marine Reserve comes from local, mainland, and foreign fishing targeting marine life illegally within the Reserve, such as sharks (hammerheads and other species) for their fins, and the harvest of sea cucumbers out of season.

Development threatens both land and sea species. The growth of both the tourism industry and local populations fueled by high birthrates and illegal immigration threaten the wildlife of the archipelago. The grounding of the oil tanker Jessica and the subsequent oil spill brought this threat to world attention.

Currently, the rapidly growing problems of tourism and a human population explosion are further destroying habitats.

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Rebecca Strauss, Breaking News: Darwin's Arch Collapses Scuba Diver Life, May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ Antonia Noori Farzan, Darwin's Arch, famed Galápagos rock formation, collapses from erosion The Washington Post, May 19, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ Richard Keynes, (ed.), Charles Darwin's zoology notes & specimen lists from H.M.S. Beagle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). Retrieved May 28, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Angermeyer, Johanna. My Father's Island: A Galapagos quest. Stonegate: Pelican Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0954485108

- Constant, Pierre. Galápagos: A natural history guide. Hong Kong: Odyssey, 2004. ISBN 9622177425

- Foley, Erin L. and Leslie Jermyn. Ecuador. Cultures of the World series. New York: Marshall Cavendish, 2006. ISBN 0761420507

- Heyerdahl, Thor, and Arne Skjølsvold. Archaeological evidence of pre-Spanish visits to the Galaṕagos Islands. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, no. 12. Salt Lake City: Society for American Archaeology, 1956.

- Keynes, Richard. (ed.). Charles Darwin's zoology notes & specimen lists from H.M.S. Beagle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Quammen, David. The Song of the Dodo: Island biogeography in an age of extinctions. New York: Scribner, 1996. ISBN 0684800837

- Smith, Julian. Ecuador, 3rd ed. Moon Handbooks. Emeryville, CA: Avalon Travel Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1566916103

- Stolt, Matthias. Galapagos. Bremen: Edition Temmen, 2003. ISBN 3861089092

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved May 26, 2021.

- The Galápagos. World Wildlife Fund.

- Galápagos geology. Galápagos Geology on the Web.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/120px-Galapagos_Penguin_(47725915092).jpg)