Galle

| Old Town of Galle and its Fortifications* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv |

| Reference | 451 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1988 (10th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

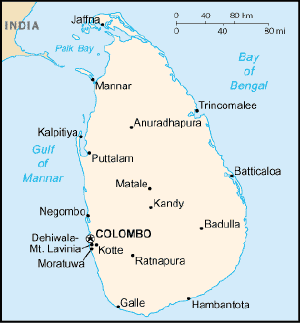

Galle (காலி in Tamil) (pronounced as one syllable in English, IPA: /gɔːl/, the same as "Gaul," and in Sinhalese, IPA: [gaːlːə]) refers to a town situated on the southwestern tip of Sri Lanka, 119 kilometers from Colombo. Galle had been known as Gimhathiththa (although Ibn Batuta in the fourteenth century refers to it as Qali) before the arrival of the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, when it served as the main port on the island. Galle reached the height of its development in the eighteenth century, before the arrival of the British, who developed the harbor at Colombo.

Galle blends both the past and the present, the native and the colonial. The first Portuguese fleet, led by Laurenco De Almeida, sailed into the country nearly five centuries ago at the port. The Dutch, more than three centuries ago, built their famous ninety-acre fort which still retains its old world charm with its high ramparts and ornate pepperpot towers. The Fort, like most of the forts in Sri Lanka, sits on a small peninsula, belonging to the sea as much as to the land. Treacherous rocks sit in the water near the fort, along with a treacherous current, requiring a pilot to approach it. Shipwrecks litter the sea floor here. Attackers could only attempt a conquest from the land side, where the Zon, Maan and Ster bastions block passage. Cottage industries, such as turtle-shell ware, ebony ornaments and beeralu lace, flourished about a century or so ago before gradually declining or passing into oblivion. Galle once rose to the leading center of the native arts and crafts.

In the aftermath of Independence, Galle has found itself a city with a European flavor in the midst of Sri Lankan culture. Although the legacy of European colonialism leaves an unpleasant after taste, the citizens of Galle have inherited a city of charm and uniqueness. In Galle, the West came to the East, leaving the opportunity for a dialog of culture, language, and architecture.

Description

Galle presents the best example of a fortified city built by Europeans in south and southeast Asia, showing the interaction between European architecture styles and south Asian traditions. It constitutes the largest remaining fortress in Asia built by European colonialists. Other prominent landmarks in Galle include St. Mary's Cathedral founded by Jesuit priests, one of the main Shiva temples on the island, and the Amangalla, a historic luxury hotel.

Galle, the main town in the most southerly part of the island, has a population of around 100,000, and is connected by rail to Colombo and Matara. It serves as home to a cricket ground, the Galle International Stadium, rebuilt after the 2004 tsunami. Test matches resumed there on December 18, 2007. Rumassala Kanda, a large mound-like hill, forms the eastern protective barrier to the Galle harbor. Local tradition associates this hill with some events of the Ramayana.

Old Galle constitutes a "living museum" as well as host to museums, especially the Dutch Period Museum on Leyn Baan.[1] That privately-owned establishment houses an array of Dutch-period artifacts ranging from rare porcelain to obscure bric-a-brac. The dilapidated Groot Kerk or Dutch Reformed Church, located, on Church Street just south of the New Oriental Hotel, had been founded in 1754 by the then Dutch Governor of Galle, Capar de Jong. The ancient Dutch gravestones, both in the churchyard and within the nave, have distinguishing skull and skeleton markings. That serves as grim reminders of the tenuous nature of life in eighteenth-century Galle, as well as characteristic of the dour nature of contemporary Dutch Protestantism.

Opposite the Groot Kerk stands the old Dutch Government House, a colonial building bearing the date 1683 and the cockerel crest of Galle over the main entrance. The original Dutch ovens still survive within the building, currently used as a commercial office. Further south along Church Street stands the Catholic All Saints Church, built by the British in 1868 and consecrated in 1871. Beyond that, at the southernmost point of the peninsula, a small Moorish community still prospers, with a madrassa or Islamic college and two mosques, the most impressive of the Meera Masjid.

On December 26, 2004, the massive Boxing Day Tsunami, caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake that occurred a thousand miles away off the coast of Indonesia, devastated the city. Thousands died in the city alone. The Dutch fort, also known as Ramparts of Galle, withstood the mighty Boxing Day tsunami which destroyed the Galle town.

History

According to James Emerson Tennent, Galle had been the ancient seaport of Tarshish, from which King Solomon drew ivory, peacocks and other valuables. Cinnamon had been exported from Sri Lanka as early as 1400 B.C.E. and the root of the word itself may come from Hebrew, so Galle may have been the main port for the spice.

Galle had been a prominent seaport long before western rule in the country. Persians, Arabs, Greeks, Romans, Malays and Indians traded through Galle port. Galle clearly had been chosen as a port for excellent strategic reasons. It has a fine natural harbor protected, to the west, by a south-pointing promontory. The frozen waste of the Antarctic, over five thousand miles distant, constitutes the next piece of land, literally.

Perhaps the earliest recorded reference to Galle comes from the great Arab traveler Ibn Battuta, who visited the port—which he calls Qali—in the mid-fourteenth century. The Portuguese first arrived in 1505, when a fleet commanded by Lorenzo de Almeida took shelter from a storm in the lee of the town. Clearly the strategic significance of the harbor impressed the Portuguese, for eighty-two years later, in 1587, they seized control of the town from the Sinhala kings and began the construction of Galle Fort. That event marked the beginning of almost four centuries of European domination of the city, resulting in the fascinating hybrid—architecturally, culturally and ethnically—which Galle constitutes today.

In 1640, the Portuguese surrendered the city to the Dutch East India Company. The Dutch built the present Fort in the year 1663. They built a fortified wall, using solid granite, and built three bastions, known as "sun," "moon" and "star." After the British took over the country from the Dutch in the year 1796, they preserved the Fort unchanged, and used it as the administrative center of Galle. In 1947, when Ceylon gained its independence from the British, Galle became, once again, an independent city. By that time the long years of association with European colonialism had left an indelible stamp on the city which makes it unique in today's Sri Lanka. In recognition of that, UNESCO declared the Old City of Galle, essentially the fort and its surroundings, a World Heritage Site in 1988.

Galle Fort

The Portuguese first built Galle fort, which the Dutch modified during the seventeenth century. During the Dutch period in Ceylon, the Dutch brought laborers from Indonesia and Mozambique to build the massive fort. Even today, after 400 years of existence, it looks new and polished. Today many Dutch people who still own most of the properties inside the fort look to make it one of the modern wonders of the world. The citizens of Dutch fort in Galle have been trying to make this a free port and a free trade zone. If successful, the companies and individuals who reside inside the city will be free of taxes. Currently, businesses have a ten year period of no withholding tax, no tax on capital gains, no corporate tax, no VAT, and no profit tax from the start of the business.

Some of the famous Moor (Muslim) families living inside the fort include the Noordeen Cassim's family and Fatima Koppen Adams families. Many Moor families live inside the fort along with Dutch, English, Portuguese and Germans. Galle Fort covers an area of thirty six hectares and encloses several museums, a clock tower, churches, mosques, a lighthouse and several hundred private dwellings. Tellingly, no major Buddhist temples exist within the walls. The Dutch may have been gone for more than two centuries, but their cultural influence, best represented by the crumbling Groote Kerk, local seat of the Dutch Reformed Church, remains palpable.

Galle Lighthouse

The Sri Lanka Ports Authority operates and maintains Dondra Head Lighthouse, an offshore Lighthouse in Galle, Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka's oldest light station dating back to 1848, the original lighthouse had been destroyed by fire in 1934. The light station stands within the walls of the ancient Galle fort, the country's most often visited lighthouse.

Entrance Gate

The British broke through the rampart between the Zon and Maan bastions to create a larger entrance gate, replacing the old, smaller one near the harbor. The road leading up to the old gate used to be a causeway, with on the left the water of the bay and on the right a swampy area. A large moat runs along the wall of the ramparts connecting the Zon, Maan and Ster bastions. The harbor no longer exists.

Inside the Fort

The real charm of Old Galle lies in the quiet back streets and alleyways of the historic fort, which have changed little, if at all, since colonial times. Two entries exist into the fort, the Main Gate, built by the British in 1873 which pierces the main ramparts between the Sun and Moon Bastions, and the more venerable Old Gate, further to the east on Baladaksha Maw (or Customs Road). The British coat of arms carved into its outer stone lintel distinguishes the Old Gate. On the inside the initials VOC, flanked by two lions and surmounted by a cock, appear deeply etched on the inner lintel. That latter inscription, dated 1669, stands for the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or United East India Company. The cockerel has become a symbol of Galle, and it is even suggested that the name of the city derives from galo, meaning "rooster" in Portuguese. Just beyond the Old Gate stands the Zwart Bastion, or Black Fort—the oldest fortification surviving in Galle, and thought to be of Portuguese origin.

With the exception of Zwart Bastion, the interior of Galle Fort strongly resonates the Dutch period. Several of the narrow streets still bear Dutch names such as Leyn Baan or "Rope Lane" and Mohrische Kramer Straat or "Street of the Moorish Traders." Beneath the streets an efficient, Dutch-built sewerage system still flushes out twice daily by the rising tides of the Indian Ocean. Many of the streets, lined with formerly opulent buildings, have characteristic large rooms, arched verandas and windows protected by heavy, wooden-louvered shutters.

The British-built Clock Tower and a small roundabout located immediately within the Main Gate dominates the northern part of the fort. From here Church Street curves away south past the National Cultural Museum with rather poorly displayed exhibits of the city's colonial heritage. The National Maritime Museum on nearby Queen Street, a massively fortified Dutch warehouse, displays various fishing and other maritime artifacts.

The final section between the Aeolus and Star bastions, part of a military base, has been placed off limits to the public. While some of the bastions retain their original Dutch names, the Triton, Aeolus, Neptune and Aurora bastions had been renamed by the British in honor of the Royal Navy ships of the line which took part in the British seizure of Sri Lanka from the Dutch during the Napoleonic Wars.[2]

Ramparts

Galle's Dutch defenders feared, mistakenly, as it turned out, assault by land from the Sinhala kings more than the threat by sea from the British. Accordingly, they built three great ramparts at tremendous cost in both labor and treasure to isolate the peninsula from the mainland. Stretching across the peninsula from west to east, those include the Star Bastion, the Moon Bastion and the Sun Bastion. Rising high above the present-day esplanade, those deep, crenellated fortifications must once have appeared all-but-impregnable to the armies of Kandy and Colombo.

The walls of the Old City required two hours to circumvent. Only once, between the Aurora Bastion and the Main Gate, citizens had to descend into the fort itself. Nearby stands the New Oriental Hotel, built by the Dutch in 1684 as a governorial mansion. The ancient walls, dating in large part from the Dutch establishment of the fort in 1663, remain largely intact.[3]

Walking to the south, old Galle Harbor may be seen to the east. The twenty meter high lighthouse, built by the British in 1934, dominates Point Utrecht Bastion at the fort's south-eastern corner. The rampant path continues due west, skirting the Indian Ocean past Triton, Neptune and Clippenburg Bastions. Beyond Clippenburg, as the fortifications turn due north towards Star Bastion and the main northern defenses, a Sri Lankan Army camp resides at Aeolus Bastion.

The National Maritime Museum, Galle

Located within the Fort of Galle in a colonial Dutch ware-house with imposing pillars, the National Maritime Museum displays the fauna and flora of the sea. Artifacts consist of preserved material and scaled down models of whales and fishes. Generally, the Museum displays all the resources of the sea. Displays show the traditional methods of fishing diorama form with life sized models. Some artifacts of underwater archaeology are on display. The 'walk-into-the sea' diorama, showing the natural coral beds, sea grass beds and deep sea fishes constitutes an interesting experiment. Finally, one leaves the museum seeing the causes of sea pollution, coast erosion and methods used to combat those problems.[4]

Demographics

Galle, a sizeable town by Sri Lankan standards, has a population of 90,934, the majority of Sinhalese ethnicity. A large Sri Lankan Moor minority descend from the Arab traders that established the ancient port of Galle.

| Ethnicity | Population | % Of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Sinhalese | 66,114 | 72.71 |

| Sri Lankan Tamils | 989 | 1.09 |

| Indian Tamils | 255 | 0.28 |

| Sri Lankan Moors | 23,234 | 25.56 |

| Other (including Burgher, Malay) | 342 | 0.38 |

| Total | 90,934 | 100[5] |

Gallery

See also

- 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake

- Sri Lanka

- Portuguese Empire

- Dutch Empire

- British Empire

- Goa

- Historic Center of Macau

Notes

- ↑ Elke Frey, Gerhard Lemmer, and Jayanthi Namasivayam, Sri Lanka (Munich: Nelles, 2001), 200.

- ↑ R. K. De Silva and W. G. M. Beumer, Illustrations and views of Dutch Ceylon, 1602-1796: a comprehensive work of pictorial reference with selected eye-witness accounts (London: Serendib Publications, 1988), 155.

- ↑ Emir Fethi Caner and H. Edward Pruitt, The costly call: book 2, the untold story (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2006), 85.

- ↑ Banister Fletcher and Dan Cruickshank, Sir Banister Fletcher's A history of architecture (London: Architectural Press, 1996), 1261.

- ↑ 2001 Census

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Caner, Emir Fethi, and H. Edward Pruitt. The Costly Call: Book 2, The Untold Story. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2006. ISBN 978-0825435645

- De Silva, R. K., and W. G. M. Beumer. Illustrations and Views of Dutch Ceylon, 1602-1796: A comprehensive work of pictorial reference with selected eye-witness accounts. London: Serendib Publications, 1988. ISBN 978-9004089792

- Fletcher, Banister, and Dan Cruickshank. Sir Banister Fletcher's A history of Architecture. London: Architectural Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0750622677

- Frey, Elke, Gerhard Lemmer, and Jayanthi Namasivayam. Sri Lanka. Munich: Nelles, 2001. ISBN 3886182290

External links

All links retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Old Town of Galle and its Fortifications, UNESCO World Heritage

- Official website of the Sri Lanka Tourism Board

- A Historic tour through the city of Galle

- The old world's romantic city: Galle!

- Galle - A Port City in History

| ||||||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.