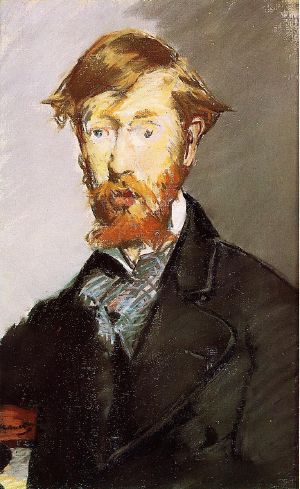

George Moore

George Augustus Moore (February 24, 1852 – January 21, 1933) was an Irish novelist, short story writer, poet, art critic, memoirist and dramatist. Moore came from a Roman Catholic landed family, originally intended to be an artist, and studied art in Paris during the 1870s. There he befriended many of the leading French artists and writers of the day.

As a naturalistic writer, he was among the first English-language authors to absorb the lessons of the French realists, and was particularly influenced by the works of Émile Zola. His short stories influenced the early writings of James Joyce. Moore's work is sometimes seen as outside the mainstream of both Irish and British literature, but he is as often seen as the first great modern Irish novelist.

Family background and early life

George Moore and his four siblings, Maurice (1854), Augustus (1856), Nina (1858) and Julian (1867), were born in Moore Hall, near Lough Carra, County Mayo.[1] The house was built by his paternal great-grandfather, another George Moore, who had made his fortune as a wine merchant in Alicante.[2] The novelist's grandfather was a friend of Maria Edgeworth and wrote An Historical Memoir of the French Revolution. His great-uncle, John Moore, was president of the short-lived Republic of Connaught[3] during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. During Moores's childhood, his father, George Henry Moore, having sold his stable and hunting interests during the Irish Famine, served as an Independent Member of Parliament (MP) for Mayo in the British House of Commons in London from 1847–1857.[4] Renowned as a good landlord, George Henry fought for tenants' rights.[5] He was a founder of the Catholic Defence Association. The estate consisted of 50 km² in Mayo with a further 40 ha in County Roscommon.

As a child, Moore enjoyed the novels of Walter Scott, which his father read to him.[6] He had spent a good deal of time outdoors with his brother, Maurice. He also became friendly with the young Willie and Oscar Wilde, who spent their summer holidays at nearby Moytura. Oscar was to later quip of Moore: "He conducts his education in public".[7] His father had again turned his attention to horse breeding and in 1861 brought his champion horse Croaghpatrick to England for a successful racing season, together with his wife and nine-year-old son. For a while George was left at Cliff's stables until his father decided to send George to his alma mater facilitated by his winnings. Moore's formal education started at St. Mary's College, Oscott, a Catholic boarding school near Birmingham, where he was the youngest of 150 boys. He spent all of 1864 at home, having contracted a lung infection brought about by a breakdown in his health. His academic performance was poor while he was hungry and unhappy. In January 1865, he returned to St. Mary's College with his brother Maurice, where he refused to study as instructed and spent time reading novels and poems.[8] That December the principal, Spencer Northcote, wrote a report that: "he hardly knew what to say about George." By the summer of 1867 he was expelled, for (in his own words) 'idleness and general worthlessness', and returned to Mayo. His father once remarked, about George and his brother Maurice: "I fear those two redheaded boys are stupid," an observation which proved untrue for all four boys.[9]

London and Paris

In 1868, Moore's father was again elected MP {Member of Parliament) for Mayo and the family moved to London the following year. Here, Moore senior tried, unsuccessfully, to have his son follow a career in the military though, prior to this, he attended the School of Art in the South Kensington Museum where his achievements were no better. He was freed from any burden of education when his father died in 1870.[10] Moore, though still a minor, inherited the family estate, that consisted of well over 12,000 acres and was valued at £3,596. He handed it over to his brother Maurice to manage and in 1873, on attaining his majority, moved to Paris to study art for ten years. It took him several attempts to find an artist who would accept him as a pupil. Monsieur Jullian, who had previously been a shepherd and circus masked man, took him on for 40 Francs a month.[11] At Académie Jullian he met Lewis Weldon Hawkins who became Moore's flat-mate and whose trait, as a failed artist, show up in Moore's own characters.[12] He met many of the key artists and writers of the time, including Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Alphonse Daudet, Stéphane Mallarmé, Ivan Turgenev and, above all, Emile Zola, who was to prove an influential figure in Moore's subsequent development as a writer.

Moore was forced to return to Ireland in 1880 to raise £3,000 to pay debts incurred on the family estate. During his time back in Mayo, he gained a reputation as a fair landlord, continuing the family tradition of not evicting tenants and refusing to carry firearms when traveling round the estate.

While in Ireland, he decided to abandon art and move to London to become a professional writer. His first book, a collection of poems called The Flowers of Passion, appeared in 1877 and a second collection, Pagan Poems, followed in 1881. These early poems reflect his interest in French symbolism and are now almost entirely neglected. He then embarked on a series of novels in the realist style. His first novel, A Modern Lover (1883), was banned in England because of its, for the times, explicit portrayal of the amorous pursuits of its hero. At this time the British circulating libraries, such as Maudie's Select Library, controlled the market for fiction and the public, who paid fees to borrow their books, expected them to guarantee the morality of the novels available.[13] His next book, A Mummers Wife (1885) is widely recognized as the first major novel in the realist style in the English language. This too was regarded as unsuitable by Maudie's and W. H. Smith refused to stock it on their news-stalls. Despite this, during its first year of publication the book was in its fourteenth edition mainly due to the publicity garnered by its opponents.[14] Other realist novels by Moore from this period include Esther Waters (1894), the story of an unmarried housemaid who becomes pregnant and is abandoned by her footman lover, and A Drama in Muslin (1886), a satiric story of the marriage trade in Anglo-Irish society that hints at same-sex relationships among the unmarried daughters of the gentry. Both of these books have remained almost constantly in print since their first publication. His 1887 novel A Mere Accident is an attempt to merge his symbolist and realist influences. He also published a collection of short stories: Celibates (1895).

Because of his willingness to tackle such issues as prostitution, extramarital sex and lesbianism in his fiction, Moore's novels met with some disapprobation at first. However, a public taste for realist fiction was growing, and this, combined with his success as an art critic with the books Impressions and Opinions (1891) and Modern Painting (1893), which was the first significant attempt to introduce the Impressionists to an English audience, meant that he was eventually able to live off the proceeds of his literary work.

Dublin and the Celtic Revival

In 1901, Moore returned to Ireland to live in Dublin at the suggestion of his cousin and friend, Edward Martyn. Martyn had been involved in Ireland's cultural and dramatic movements for some years, and was working with Lady Gregory and William Butler Yeats to establish the Irish Literary Theatre. Moore soon became deeply involved in this project and in the broader Irish Literary Revival. He had already written a play, The Strike at Arlingford (1893), which was produced by the Independent Theatre. His satirical comedy The Bending of the Bough (1900) was staged by the Irish Literary Theatre as was Diarmuid and Grania, co-written with Yeats, in 1901.

He also published two books of prose fiction set in Ireland around this time, a second book of short stories, The Untilled Field (1903) and a novel, The Lake (1905). The stories in The Untilled Field, which deal with themes of clerical interference in the daily lives of the Irish peasantry and of emigration, were originally written to be translated into Irish to serve as models for other writers working in the language. Three of the translations were published in the New Ireland Review, but publication was then paused because of the anti-clericism evident in the stories. The entire collection was translated by Tadhg Ó Donnchadha and Pádraig Ó Súilleabháin and published in a parallel-text edition by the Gaelic League as An-tÚr-Ghort in 1902. Moore then further revised the texts for the English edition. These stories were influenced by Turgenev's A Sportsman's Sketches, a book recommended to Moore by W. K. Magee, a sub-librarian of the National Library of Ireland, who even suggested that Moore "was best suited to become Ireland's Turgenev," one of Moore's heros.[15] They are generally recognized as representing the birth of the Irish short story as a literary genre and are clear forerunners of Joyce's Dubliners collection, which is concerned with similarly quotidian themes but in an urban setting.

In 1903, following a disagreement with his brother, Maurice, about the religious upbringing of his nephews, Rory and Toby, Moore declared himself to be a Protestant in a letter to the Irish Times newspaper.[16] During this time, he published another book on art, Reminiscences of the Impressionist Painters (1906). Moore remained in Dublin until 1911. He published an entertaining, gossipy, three-volume memoir of his time there under the collective title Hail and Farewell (1914). Moore himself said of these memoirs: "One half of Dublin is afraid it will be in the book, and the other is afraid that it won't."

Later life and work

Moore returned to London, where, with the exception of frequent trips to France, he was to spend the rest of his life. In 1913, he travelled to Jerusalem to research background for his novel The Brook Kerith (1916).[17] This book, based on the supposition that a non-divine Jesus Christ did not die on the cross but was nursed back to health and eventually travelled to India to learn wisdom, saw Moore once again embroiled in controversy. Other books from this period include a further collection of short-stories called A Storyteller's Holiday (1918), a collection of essays called Conversations in Ebury Street (1924) and a play, The Making of an Immortal (1927). He also spent considerable time revising and preparing his earlier writings for a uniform edition.

Partly due to Maurice Moore's pro-treaty activity, Moore Hall was burnt out by anti-treaty forces in 1923, during the final months of the Irish Civil War.[18] Moore eventually received compensation of £7,000 from the government of the Irish Free State. By this time George and Maurice had become estranged, mainly because of an unflattering portrait of the latter which appeared in Hail and Farewell, which is considered to be autobiographical in nature, leading to a new literary form, the fictionalized biography. Tension also arose as a result of Maurice's active support of the Roman Catholic Church, to whom he frequently made donations from estate funds.[19] Moore later sold a large part of the estate to the Irish Land Commission for £25,000.

He was friendly with many members of the expatriate artistic communities of London and Paris, and conducted a long-lasting affair with Lady Maud Cunard. It is now believed that he was the natural father of her daughter, the well-known publisher and art patron, Nancy Cunard. Gertrude Stein mentions Moore in her The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), describing him as "a very prosperous Mellon's Food baby."

Moore's last novel, Aphroditis in Aulis, was published in 1930. He contracted uremia and died at his home at Ebury Street in the London district of Pimlico. When he died, he left a fortune of £80,000, none of which was left to his brother. He was cremated in London and an urn containing his ashes was interred on Castle Island in Lough Carra in view of the ruins of Moore Hall.

Legacy

Moore helped to popularize realist fiction in the English language. His works influenced the early James Joyce. His most significant legacy would be his contributions to the Celtic Revival, especially the rise of the Abbey Theatre, which played in significant role in both the rise of modern Irish literature and the creation of Irish political consciousness.

Works

- Flowers of Passion London: Provost & Company, 1878

- Martin Luther: A Tragedy in Five Acts London: Remington & Company, 1879

- Pagan Poems London: Newman & Company, 1881

- A Modern Lover London: Tinsley Brothers, 1883

- A Mummer's Wife London: Vizetelly & Company, 1885

- Literature at Nurse London: Vizetelly & Company, 1885

- A Drama in Muslin London: Vizetelly & Company, 1886

- A Mere Accident London: Vizetelly & Company, 1887

- Parnell and His Island London; Swan Sonnershein Lowrey & Company, 1887

- Confessions of a Young Man Swan Sonnershein Lowrey & Company, 1888

- Spring Days London: Vizetelly & Company, 1888

- Mike Fletcher London: Ward & Downey, 1889

- Impressions and Opinions London; David Nutt, 1891

- Vain Fortune London: Henry & Company, 1891

- Modern Painting London: Walter Scott, 1893

- The Strike at Arlingford London: Walter Scott, 1893

- Esther Waters London: Walter Scott, 1894

- Celibates London: Walter Scott, 1895

- Evelyn Innes London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1898

- The Bending of the Bough London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1900

- Sister Theresa London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1901

- The Untilled Field London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1903

- The Lake London: William Heinemann, 1905

- Memoirs of My Dead Life London: William Heinemann, 1906

- The Apostle: A Drama in Three Acts Dublin: Maunsel & Company, 1911

- Hail and Farewell London: William Heinemann, 1911, 1912, 1914

- The Apostle: A Drama in Three Acts Dublin: Maunsel & Company, 1911

- Elizabeth Cooper Dublin: Maunsel & Company, 1913

- Muslin London: William Heinemann, 1915

- The Brook Kerith: A Syrian Story London: T. Warner Laurie, 1916

- Lewis Seymour and Some Women New York: Brentano's, 1917

- A Story-Teller's Holiday London: Cumann Sean-eolais na hEireann (privately printed), 1918

- Avowels London: Cumann Sean-eolais na hEireann (privately printed), 1919

- The Coming of Gabrielle London: Cumann Sean-eolais na hEireann (privately printed), 1920

- Heloise and Abelard London: Cumann Sean-eolais na hEireann (privately printed), 1921

- In Single Strictness London: William Heinemann, 1922

- Conversations in Ebury Street London: William Heinemann, 1924

- Pure Poetry: An Anthology London: Nonesuch Press, 1924

- The Pastoral Loves of Daphnis and Chloe London: William Heinemann, 1924

- Daphnis and Chloe, Peronnik the Fool New York: Boni & Liveright, 1924

- Ulick and Soracha London: Nonesuch Press, 1926

- Celibate Lives London: William Heinemann, 1927

- The Making of an Immortal New York: Bowling Green Press, 1927

- The Passing of the Essenes: A Drama in Three Acts London: William Heinemann, 1930

- Aphrodite in Aulis New York: Fountain Press, 1930

- A Communication to My Friends London: Nonesuch Press, 1933

- Diarmuid and Grania: A Play in Three Acts Co-written with W.B. Yeats, Edited by Anthony Farrow, Chicago: De Paul, 1974

Letters

- Moore Versus Harris Detroit: privately printed, 1921

- Letters to Dujardin New York: Crosby Gaige, 1929

- Letters of George Moore Bournemouth: Sydenham, 1942

- Letters to Lady Cunard Ed. Rupert Hart-Davis. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1957

- George Moore in Transition Ed. Helmut E. Gerber, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1968

Notes

- ↑ Adrian Frazier. George Moore, 1852–1933. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 11.

- ↑ Kevin Coyne. The Moores of Moorehal. Mayo Ireland Ltd.,

- ↑ Frazier (2000), 1–5.

- ↑ Norman A. Jeffares. George Moore. (London: The British Council & National Book League, 1965), 7

- ↑ Frazier (2000), 1–2.

- ↑ Jay Jernigan. "The Forgotten Serial Version of George Moore's Esther Waters." Nineteenth-Century Fiction 23(1) (June 1968): 99-103.

- ↑ Arnold T. Schwab, Review of "George Moore: A Reconsideration," by Malcolm Brown. Nineteenth-Century Fiction10(4) (March, 1956): 310-314.

- ↑ Frazier, 14–16.

- ↑ Anthony Farrow. George Moore. (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1978), 11-13.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), 28–29.

- ↑ Farrow (1978), 13–14.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), 48–49.

- ↑ Harry Thurston Peck. The Personal Equation. (London; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1972) (original 1898), 90–95.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), 306, 326.

- ↑ Ibid., 331.

- ↑ The Brook Kerith by George Moore. fullbooks.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2007.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), 434.

- ↑ Ibid. (2000), 331, 360–363, 382–389.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carra Historical Society, The Moores of Moore Hall: A short History. C.H.S., 1989.

- Farrow, Anthony. George Moore. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1978. ISBN 0805766855

- Frazier, Adrian. George Moore, 1852–1933. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 0300082452

- Hone, Joseph. The Life of George Moore. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1973. ISBN 978-1163137284

- Igoe A Literary Guide to Dublin. London: Methuen, 2003 (original 1994). ISBN 0413691209

- Jaffares, Norman A. George Moore. London: The British Council & National Book League, 1965. OCLC 62990264

- Moore, George, and Rupert Hart-Davis. Letters to Lady Cunard, 1895-1933. Greenwood Press, 1979.

- Peck, Harry T. The Personal Equation. London; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1972 (original 1898). ISBN 978-0836927092

External links

All links retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Works by George Moore. Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.