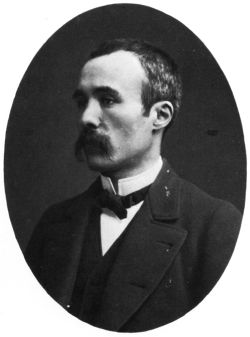

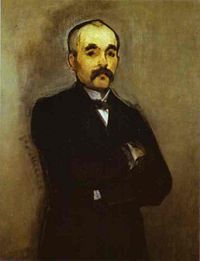

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau[1] (Mouilleron-en-Pareds (Vendée), September, 28 1841 – November 24, 1929) was a French statesman, physician and journalist. He led France during World War I and was one of the major voices behind the Treaty of Versailles, chairing the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. He famously anticipated that the German economy would quickly recover because German industry had largely survived the war, while France's had not. He did not think that the measures taken at the Peace Conference would prevent another war. He supported the setting up of the League of Nations but thought its goals were too utopian. A career politician, he gave his nation strong leadership during one of its darkest hours in history, bolstering public confidence that Germany could be defeated. He failed to win the post-war election, however, because the French people believed that he had not won all French demands at the Conference, especially on the issue of reparations. The French wanted Germany to pay as much as possible, which the United States and Great Britain opposed, so Clemenceau devolved the decision to a commission. The French also favored Germany's division into smaller states.

Clemenceau, however, secured France's trusteeship of Syria and the Lebanon as well as other territories and her continued role as a major European power. Historically, this has contributed to continued French involvement in trade with the Arab world and in good relations with some countries with which other Western powers have a more strained relationship. Subsequently, France has sometimes been able to perform a mediator role. Huge tracts of the world were parceled out among the victors and the geo–political consequences of this continue to shape international affairs. MacMillan (2001) describes the Paris Peace Conference as more or less, for the six months that the powers met, a world government. Clemenceau, as chair, exercised enormous influence if not power albeit for a short period of time.

Early life

Georges Clemenceau was born in a small village in the province of Vendée, France on September 28, 1841. He looked up to his father who fostered his strong republican political views, although he was the grandson of the noble seigneur du Colombier, who in turn descended nine times from King Jean de Brienne of Jerusalem, two from King Fernando III of Castile of Castile and one from King Edward I of England of England. With a group of students he began publishing a paper Le Travail ("Work"). This was considered radical by Napoleon III and when affixing posters convening a demonstration he was seized by French police. He spent 73 days in prison. When he was released he began another paper called Le Matin ("Morning"), but this again caused him trouble with the police. He eventually became a doctor of medicine May 13, 1865 with a thesis entitled De la génération des éléments atomiques (On the generation of the atomic elements).

After studying medicine in Nantes he traveled to the United States and began living in New York. He was impressed by the freedom of speech and expression which he observed—something he had not witnessed in France under the reign of Napoleon III. He had a great admiration for the politicians who were forging American democracy and considered settling permanently in the country. He began teaching at an private school for young women school in Connecticut and eventually married one of his students, Mary Plummer, in 1869. They had three children together but divorced in 1876.

Clemenceau left New York and returned to France, settling in Paris. He established himself as a doctor, adopting medicine as his profession. He settled in Montmartre in 1869 and following the inauguration of the Third Republic (1870–1940), was sufficiently well known to be nominated mayor of the 18th arrondissement of Paris (Montmartre) — an unruly district over which it was a difficult task to preside.

During the Franco–Prussian War, Clemenceau remained in Paris and was resident throughout the siege of Paris. When the war ended on January 28, 1871 Clemenceau stood for election as mayor and on February 8, 1871 he was elected as a Radical to the National Assembly for the Seine département. As a Radical, he voted against the proposed peace treaty with newly formed Germany.

On March 20, 1871 he introduced a bill in the National Assembly at Versailles, on behalf of his Radical colleagues, proposing the establishment of a Paris municipal council of 80 members; but he was not re–elected at the elections on March 26. Clemenceau played an important role in the Paris Commune. On March 18, 1871 he witnessed firsthand the murder of General Lecomte and General Thomas by communard members of the National Guard. In his memoirs, he claims that he tried to prevent the murder of the generals and the murder of several army officers and policemen he saw being incarcerated by the National Guard, but this claim has neither been confirmed nor denied. His suspected anti–communard sympathies led to him being placed under surveillance by the Central Committee at the Hôtel de Ville, the main Communard body responsible for running Paris during the Commune. The Central Committee ordered his arrest, but within a day he had been cleared and was released. During April and May, Clemenceau was one of several Parisian mayors who tried unsuccessfully to mediate between the Communard government in Paris and the Republican National Assembly at Versailles. When the loyalist Versaillais army broke into Paris on 21 May to end the commune and place Paris back under the jurisdiction of the French government, Clemenceau refused to give any help to the Communard government. After the ending of the Commune, Clemenceau was accused by various witnesses of not having intervened to save Generals Lecomte and Thomas when he might have done so. Although he was cleared of this charge, it led to a duel, for which he was prosecuted and sentenced to a fine and a fortnight's imprisonment.

He was elected to the Paris municipal council on 23 July 1871 for the Clignancourt quartier, and retained his seat till 1876, passing through the offices of secretary and vice–president, and becoming president in 1875.

In 1876, he stood again for the Chamber of Deputies, and was elected for the 18th arrondissement. He joined the far left, and his energy and mordant eloquence speedily made him the leader of the Radical section. In 1877, after the 16 May 1877 crisis|Seize Mai crisis, he was one of the republican majority who denounced the de Broglie ministry, and he took a leading part in resisting the anti–republican policy of which the Seize Mai incident was a manifestation. His demand in 1879 for the indictment of the de Broglie ministry brought him into particular prominence.

In 1880, he started his newspaper, La Justice, which became the principal organ of Parisian Radicalism. From this time onwards, throughout Jules Grévy's presidency, his reputation as a political critic and destroyer of ministries who yet would not take office himself grew rapidly. He led the Extreme Left in the Chamber. He was an active opponent of Jules Ferry's colonial policy and of the Opportunist party, and in 1885 it was his use of the Tonkin disaster which principally determined the fall of the Ferry cabinet.

At the elections of 1885 he advocated a strong Radical programme, and was returned both for his old seat in Paris and for the Var, selecting the latter. Refusing to form a ministry to replace the one he had overthrown, he supported the Right in keeping Freycinet in power in 1886, and was responsible for the inclusion of General Boulanger in the Freycinet cabinet as war minister. When Boulanger showed himself as an ambitious pretender, Clemenceau withdrew his support and became a vigorous opponent of the Boulangist movement, though the Radical press and a section of the party continued to patronize the general.

By his exposure of the Wilson scandal,[2] and by his personal plain speaking, Clemenceau contributed largely to Jules Grévy's resignation of the presidency in 1887, having himself declined Grévy's request to form a cabinet on the downfall of Maurice Rouvier's Cabinet. He was also primarily responsible, by advising his followers to vote for neither Floquet, Ferry, or Freycinet, for the election of an "outsider" (Carnot) as president.

The split in the Radical party over Boulangism weakened his hands, and its collapse made his help unnecessary to the moderate republicans. A further misfortune occurred in the Panama affair, as Clemenceau's relations with Cornelius here led to his being included in the general suspicion. Although he remained the leading spokesman of French Radicalism, his hostility to the Russian alliance so increased his unpopularity that in the 1893 election he was defeated for his Chamber seat, having held it continuously since 1876.

After his 1893 defeat, Clemenceau confined his political activities to journalism. On January 13, 1898 Clemenceau, as owner and editor of the Paris daily L'Aurore, published Emile Zola's "J'accuse" on the front page of his paper. Clemenceau decided that the controversial story that would become a famous part of the Dreyfus Affair would be in the form of an open letter to the President, Félix Faure. Once he realized that Dreyfus was innocent, he started an eight-year campaign to clear his name. It was this campaign that catapulted him into politics, and led to his seeking election to the Senate.

In 1900, he withdrew from La Justice to found a weekly review, Le Bloc, which lasted until March 1902. On April 6, 1902 he was elected senator for the Var, although he had previously continually demanded the suppression of the Senate. He sat with the Radical–Socialist Party , and vigorously supported the Combes ministry. In June 1903, he undertook the direction of the journal L'Aurore, which he had founded. In it he led the campaign for the revision of the Dreyfus affair, and for the separation of Church and State.

In March 1906, the fall of the Rouvier ministry, owing to the riots provoked by the inventories of church property, at last brought Clemenceau to power as Minister of the Interior in the Sarrien cabinet. The miners' strike in the Pas de Calais after the disaster at Courrieres, leading to the threat of disorder on May 1, 1906, obliged him to employ the military; and his attitude in the matter alienated the Socialist party, from which he definitively broke in his notable reply in the Chamber to Jean Jaurès in June 1906.

This speech marked him out as the strong man of the day in French politics; and when the Sarrien ministry resigned in October, he became premier. During 1907 and 1908 his premiership was notable for the way in which the new entente with England was cemented, and for the successful part which France played in European politics, in spite of difficulties with Germany and attacks by the Socialist party in connection with Morocco.

On July 20, 1909, however, he was defeated in a discussion in the Chamber on the state of the navy, in which bitter words were exchanged between him and Delcassé. He resigned at once, and was succeeded as premier by Aristide Briand, with a reconstructed cabinet.

World War I

When World War I broke out in 1914 Clemenceau refused to act as justice minister under the French Prime Minister René Viviani.

In November 1917, Clemenceau was appointed prime minister. Unlike his predecessors, he immediately halted disagreement and called for peace among senior politicians.

When Clemenceau became Prime Minister in 1917 victory seemed to be a long way off. There was little activity on the Western Front because it was believed that there should be limited attacks until the American support arrived in 1919. At this time, Italy was on the defensive, Russia had virtually stopped fighting—and it was believed they would be making a separate peace with Germany. At home the government had to combat defeatism, treason, and espionage. They also had to handle increasing demonstrations against the war, scarcity of resources and air raids—which were causing huge physical damage to Paris as well as damaging the morale of its citizens. It was also believed that many politicians secretly wanted peace. It was a challenging situation for Clemenceau, because after years of criticizing other men during the war, he suddenly found himself in a position of supreme power. He was also isolated politically. He did not have close links with any parliamentary leaders (especially after years of criticism) and so had to rely on himself and his own circle of friends.

Clemenceau’s ascension to power meant little to the men in the trenches at first. They thought of him as ‘Just another Politician’, and the monthly assessment of troop morale found that only a minority found comfort in his appointment. Slowly, however, as time passed, the confidence he inspired in a few began to grow throughout all the fighting men. They were encouraged by his many visits to the trenches. This confidence began to spread from the trenches to the home front and it was said "We believed in Clemenceau rather in the way that our ancestors believed in Joan of Arc."

Clemenceau was also well received by the media because they felt that France was in need for strong leadership. It was widely recognized that throughout the war he was never discouraged and he never stopped believing that France could achieve total victory. There were skeptics, however, that believed that Clemenceau, like other war time leaders, would have a short time in office. It was said that "Like everyone else ... Clemenceau will not last long—only long enough to clean up [the war]."

He supported the policy of total war—"We present ourselves before you with the single thought of total war."—and the policy of guerre jusqu'au bout (war until the end). These policies promised victory with justice, loyalty to the fighting men and immediate and severe punishment of crimes against France. Joseph Caillaux, a German appeaser and former French prime minister, adamantly disagreed with Clemenceau’s policies. Caillaux was an avid believer in negotiated peace—which could only be achieved by surrendering to Germany. Clemenceau believed that Caillaux was a threat to national security and that if France were to be victorious, his challenge had to be overcome. Unlike previous ministers, Clemenceau was not afraid to act against Caillaux. It was decided by the parliamentary committee that he would be arrested and imprisoned for three years. Clemenceau believed, in the words of Jean Ybarnégaray, that Caillaux’s crime "was not to have believed in victory [and] to have gambled on his nations defeat."

It was believed by some in Paris that the arrest of Caillaux and others was a sign that Clemenceau had begun a Reign of Terror in the style adopted by Robespierre. This was only really believed by the enemies of Clemenceau, but the many trials and arrests aroused great public excitement, one newspaper ironically reported "The war must be over, for no one is talking about it anymore." These trials, far from making the public fear the government, inspired confidence as the they felt that for the first time in the war, action was being taken and they were being firmly governed. Although there were accusations that Clemenceau’s ‘firm government’ was actually a dictatorship, the claims were not supported. Clemenceau was still held accountable to the people and media and he relaxed censorship on political views as he believed that newspapers had the right to criticize political figures—"The right to insult members of the government is inviolable." The only powers that Clemenceau assumed were those that he thought necessary to win the war.

In 1918, Clemenceau thought that France should adopt Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points, despite believing that some were Utopian, mainly because one of the points called for the return of the disputed territory of Alsace-Lorraine to France. This meant that victory would fulfil one war aim that was very close to the hearts of the French people. Clemenceau was also very sceptical about the League of Nations, believing that it could succeed only in a Utopian society.

As war minister Clemenceau was also in close contact with his generals. Although it was necessary for these meetings to take place, they were not always beneficial as he did not always make the most effective decisions concerning military issues. He did, however, mostly heed the advice of the more experienced generals. As well as talking strategy with the generals he also went to the trenches to see the Poilu, the French infantrymen. He wanted to talk to them and assure them that their government was actually looking after them. The Poilu had great respect for Clemenceau and his disregard for danger as he often visited soldiers only yards away from German frontlines. These visits to the trenches contributed to Clemenceau’s title Le Père de la Victoire (Father of Victory).

On March 21 the Germans began their great spring offensive. The Allies were caught off guard as they were waiting for the majority of the American troops to arrive. As the Germans advanced on March 24, the British Fifth army retreated and a gap was created in the British/French lines—giving them access to Paris. This defeat cemented Clemenceau’s belief, and that of the other allies, that a coordinated, unified command was the best option. It was decided that Marshall Ferdinand Foch would be appointed to the supreme command.

The German line continued to advance and Clemenceau believed that they could not rule out the fall of Paris. It was believed that if ‘the tiger’ as well as Foch and Henri Philippe Pétain stayed in power, for even another week, France would be lost. It was thought that a government headed by Briand would be beneficial to France because he would make peace with Germany on advantageous terms. Clemenceau adamantly opposed these opinions and he gave an inspirational speech to parliament and ‘the chamber’ voted their confidence in him 377 votes to 110.

Post WWI

As Allied counteroffensives began to push the Germans back, with the help of American reinforcements, it became clear that the Germans could no longer win the war. Although they still occupied allied territory, they did not have sufficient resources and manpower to continue the attack. As countries allied to Germany began to ask for an armistice, it was obvious that Germany would soon follow. On November 11, an armistice with Germany was signed—Clemenceau saw this as an admission of defeat. Clemenceau was embraced in the streets by and attracted admiring crowds. He was a strong, energetic, positive leader who was key to the allied victory of 1918.

It was decided that a peace conference would be held in France, officially Versailles. On December 14, Woodrow Wilson visited Paris and received an enormous welcome. His 14 points and the concept of a league of nations had made a big impact on the war weary French. Clemenceau realised at their first meeting that he was a man of principle and conscience but narrow minded.

It was decided that since the conference was being held in France, Clemenceau would be the most appropriate president—‘Clemenceau was one of the best chairmen I have ever known—firm to the point of ‘tigerishness’ when necessary, understanding, conciliatory, witty and a tremendous driver. His leadership never failed from first to last, and was never questioned.’ He also spoke both English and French, the official languages of the conference. Clemenceau thought it fitting that the Conference was being held at Versailles, since it was there that Wilhelm I of Germany had declared himself an Emperor on January 18, 1871.

The Conference progress was much slower than anticipated and decisions were being constantly adjourned. It was this slow pace that induced Clemenceau to give an interview showing his irritation to an America journalist. He said he believed that Germany had won the war industrially and commercially as their factories were intact and its debts would soon be overcome through ‘manipulation’. In a short time, he believed, the German economy would be much stronger than the French.

Clemenceau was shot by an anarchist ‘assassin’ on February 19, 1919. Seven shots were fired through the back panel of his car—one striking him in the chest. It was discovered that if the bullet had entered only millimeter to the left or right, it would have been fatal.

When Clemenceau returned to the Council of Ten on March 1 he found that little had changed. One that issue had not changed was a dispute over the long running Eastern Frontier and control of the German province Rhineland. Clemenceau believed that Germany’s possession of the territory left France without a natural frontier in the East and so simplified invasion into France for an attacking army. The issue was finally resolved when Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson guaranteed immediate military assistance if Germany attacked without provocation. It was also decided that the Allies would occupy the territory for 15 years, and that Germany could never rearm the area.

There was increasing discontent among Clemenceau, Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson about slow progress and information leaks surrounding the Council of Ten. They began to meet in a smaller group, called the Council of Four. This offered greater privacy and security and increased the efficiency of the decision making process. Another major issue which the Council of Four discussed was the future of the German Saar province. Clemenceau believed that France was entitled to the province and its coal mines after Germany deliberately damaged the coal mines in Northern France. Wilson, however, resisted the French claim so firmly that Clemenceau accused him of being ‘pro German’. Lloyd George came to a compromise and the coal mines were given to France and the territory placed under French administration for 15 years, after which a vote would determine whether the province would rejoin Germany.

Although Clemenceau had little knowledge of the Austrian–Hungarian empire, he supported the causes of its smaller ethnic groups and his adamant stance lead to the stringent terms in the Treaty of Trianon which dismantled Hungary. Rather than recognizing territories of the Austrian–Hungarian empire solely within the principles of self–determination, Clemenceau sought to weaken Hungary just as Germany and remove the threat of such a large power within Central Europe. The entire Czechoslovakian state was seen a potential buffer from Communism and this encompassed majority Hungarian territories.

Clemenceau did not have experience or knowledge in economics or finance but was under strong public and parliamentary pressure to make Germany’s reparation bill as big as possible. It was generally agreed that Germany should not pay more than it could afford, but the estimates of what it could afford varied greatly. Figures ranged between £2000 million which was quite modest compared to another estimate of £20,000 million. Clemenceau realised that any compromise would anger both the French and British citizens and that the only option was to establish a reparations commission which would examine Germany’s capacity for reparations. This meant that the French government was not directly involved in the issue of reparations.

Clemenceau's retirement and death

In the eyes of the French people, Clemenceau failed to achieve all of their demands through the Treaty of Versailles. This resulted in his loss in the French electorate in January 1920. Ironically, Clemenceau always opposed leniency toward Germany and it is believed by some that the effects of his decisions post-war, contributed to the events that lead to World War II. Clemenceau's historical reputation in the eyes of some was tainted as a result. Clemenceau is especially vilified in John Maynard Keynes "The Economic Consequences of the Peace," where it is stated that "Clemenceau had one illusion, France, and one disillusion, mankind."

In 1922, when it seemed that the United States was reverting to its policy of isolation and was disengaging from European affairs, he made a speaking tour of the USA to warn people that without the United States' help, another war would engulf Europe. He also visited the graves of French soldiers who had participated on the republican side during the American War of Independence.

After retiring from politics Clemenceau began to write his own memoirs, Grandeur et Misère d'une victoire (The Grandeur and Misery of a Victory). Clemenceau wrote about the high possibility of further conflict with Germany and predicted that 1940 would be the year of the gravest danger. George Clemenceau died in Paris on November 24, 1929 of natural causes.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gottfried, Ted. Georges Clemenceau. World leaders past & present. New York: Chelsea House, 1987 (original 1854). ISBN 978-0877545187

- Holt, Edgar. The Tiger: The Life of Georges Clemenceau. 1841–1929. London : Hamilton, 1976. ISBN 978-0241892947

- MacMillan, MacMillan. Peacemakers: Six months that changed the world. New York: John Murray, 2001. ISBN 0719562376

- Martet, Jean. Georges Clemenceau. London, New York: Longmans, Green, 1930.

- Watson, David Robin. Georges Clemenceau; a Political Biography. London: Eyre Methuen, 1974. ISBN 978-0413264107

External links

All links retrieved June 19, 2017.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Georges Clemenceau.

- South America To Day by Georges Clemenceau at archive.org. In English..

- The strongest (Les plus fort) by Georges Clemenceau at archive.org.

- The surprises of life by Georges Clemenceau at archive.org.

- At the foot of Sinai by Georges Clemenceau at archive.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.