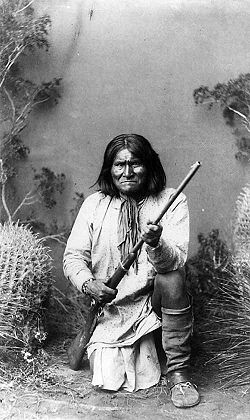

Geronimo

Geronimo (Chiricahua, Goyaałé; “One Who Yawns”; often spelled Goyathlay in English) (June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a prominent Native American leader of the Chiricahua Apache who long warred against the encroachment of the United States on tribal lands.

Geronimo embodied the very essence of the Apache values—aggressiveness and courage in the face of difficulty. He was reportedly given the name Geronimo by Mexican soldiers. They were so impressed by his adventurous stunts they nicknamed him Geronimo (Spanish for "Jerome"). At the same time, Geronimo credited his abilities—particularly his impunity to enemies' weapons—to the intervention of supernatural beings. To this day, his name is synonymous with bravery.

Early Life

Geronimo was born near Turkey Creek, a tributary of the Gila River in what is now the state of New Mexico, then part of Mexico, but which his family considered Bedonkohe Apache hell(tori) land. Geronimo was a Bedonkohe Apache. His father, Tablishim, died when his son was a child, leaving Geromino's mother, Juana, to educate him and raise him in Apache traditions. He grew up to become a respected medicine man and, later in life, an accomplished warrior who fought frequently and bravely against Mexican troops. He married a woman from the Chiricauhua band of Apache; they had three children.

On March 5, 1851, a company of four hundred Sonoran soldiers led by Colonel Jose Maria Carrasco attacked Geronimo's camp outside Janos while the men were in town trading. Among those dead were Geronimo's wife, children and mother. His chief, Mangas Coloradas, sent him to Cochise's band for help in revenge against the Mexicans. While Geronimo said he was never a chief, he was a military leader. As a Chiricahua Apache, this meant he was also a spiritual leader. He consistently urged raids and war upon many Mexican and later American groups.

Warrior

While outnumbered, Geronimo fought against both Mexican and United States troops and became famous for his daring exploits and numerous escapes from capture from 1858 to 1886. At the end of his military career, he led a small band of 38 men, women and children. They evaded five thousand American troops and many units of the Mexican army for a year. His band was one of the last major forces of independent Indian warriors who refused to acknowledge the United States government in the American West. This came to an end on September 4, 1886, when Geronimo surrendered to United States Army General Nelson A. Miles at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona. Geronimo was sent as a prisoner to Fort Pickens, Florida. In 1894 he was moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. He died of pneumonia at Fort Sill in 1909 and was buried at the Apache Indian Prisoner of War Cemetery there.

In 1905, Geronimo agreed to tell his story to S. M. Barrett, superintendent of education in Lawton, Oklahoma. Barrett had to appeal to President Roosevelt to gain permission to publish the book. Geronimo came to each interview knowing exactly what he wanted to say. He refused to answer questions or alter his narrative. Barrett did not seem to take many liberties with Geronimo's story as translated by Asa Daklugie. Frederick Turner re-edited this autobiography by removing some of Barrett's footnotes and writing an introduction for the non-Apache readers. Turner notes the book is in the style of an Apache reciting part of their rich oral history

Religion

Geronimo was raised with the traditional religious views of the Bedonkohe. When questioned about his views on life after death, he wrote in his 1903 autobiography:

As to the future state, the teachings of our tribe were not specific, that is, we had no definite idea of our relations and surroundings in after life. We believed that there is a life after this one, but no one ever told me as to what part of man lived after death...We held that the discharge of one's duty would make his future life more pleasant, but whether that future life was worse than this life or better, we did not know, and no one was able to tell us. We hoped that in the future life family and tribal relations would be resumed. In a way we believed this, but we did not know it.

Later in life Geronimo embraced Christianity, and stated:

Since my life as a prisoner has begun I have heard the teachings of the white man's religion, and in many respects believe it to be better than the religion of my fathers...Believing that in a wise way it is good to go to church, and that associating with Christians would improve my character, I have adopted the Christian religion. I believe that the church has helped me much during the short time I have been a member. I am not ashamed to be a Christian, and I am glad to know that the President of the United States is a Christian, for without the help of the Almighty I do not think he could rightly judge in ruling so many people. I have advised all of my people who are not Christians, to study that religion, because it seems to me the best religion in enabling one to live right.

In his final days he renounced his belief in Christianity, returning to the teachings of his childhood.

Alleged theft of remains

In 1918, certain remains of Geronimo were apparently stolen in a grave robbery. Three members of the Yale University secret society Skull and Bones, including Prescott Bush, father and grandfather of Presidents George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush respectively, were serving as Army volunteers at Fort Sill during World War I. They reportedly stole Geronimo's skull, some bones, and other items, including Geronimo's prized silver bridle, from the Apache Indian Prisoner of War Cemetery. The stolen items were alleged to have been taken to the society's tomb-like headquarters on the Yale University campus, and are supposedly used in rituals practiced by the group, one of which is said to be kissing the skull of Geronimo as an initiation. The story was known for many years but widely considered unlikely or apocryphal, and while the society itself remained silent, former members have said that they believed the bones were fake or non-human.

In a letter from that time period discovered by the Yale historian Marc Wortman and published in the Yale Alumni Magazine in 2006, society member Winter Mead wrote to F. Trubee Davison:

The skull of the worthy Geronimo the Terrible, exhumed from its tomb at Fort Sill by your club... is now safe inside the tomb together with his well worn femurs, bit and saddle horn.

This prompted the Indian chief's great-grandson, Harlyn Geronimo of Mescalero, New Mexico, to write to President George W. Bush in 2006 requesting his help in returning the remains:

According to our traditions the remains of this sort, especially in this state when the grave was desecrated ... need to be reburied with the proper rituals ... to return the dignity and let his spirit rest in peace.

There was apparently, no response to his letter.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Debo, Angie. Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place. Civilization of the American Indian series. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0806113333

- Geronimo, S. M. Barrett, and Frederick W. Turner. Geronimo: His Own Story. New York: Dutton, 1970. ISBN 978-0525113089

- Jeffery, David and Tom Redman. Geronimo. American Indian stories. Milwaukee, WI: Raintree Publishers, 1990. ISBN 978-0817234041

- Welch, Catherine A. Geronimo. History maker bios. Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publications, 2004. ISBN 978-0822506980

External links

All links retrieved June 20, 2017.

- Geronimo: His Own Story – Full text available through From Revolution to Reconstruction, Department of Humanities Computing

- Geronimo by Glenn Walker, Indians.org

- “Old Apache Chief Geronimo Is Dead” – New York Times

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

_and_his_warriors_in_1886.jpg/200px-Apache_chieff_Geronimo_(right)_and_his_warriors_in_1886.jpg)