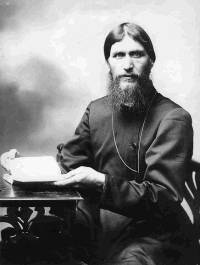

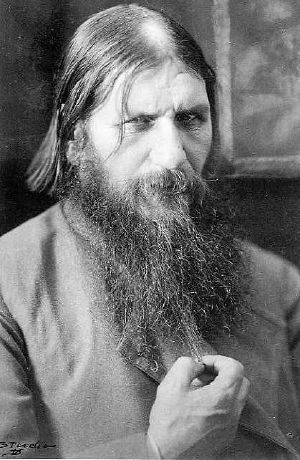

Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin, (January 10, 1869 – December 29, 1916) was a controversial Russian mystic who influenced the latter days of the Russian Tsar Nicholas II, his wife the Tsaritsa Alexandra, and their only son, the Tsarevich Alexei.

Rasputin's influence at court, coupled with reports of his corrupt lifestyle and his alleged intimate relationship with the Tsaritsa Alexandra, became a scandal in the Russian government and may have been a factor leading to the fall of the Romanov dynasty in 1917. Contemporary opinions saw Rasputin variously as a saintly holy man, visionary, healer, and prophet, and—on the other side of the coin—as a debauched religious charlatan, or "mad monk." Historians may find truth in all of these descriptions, but there is much uncertainty, for accounts of his life have often been based on dubious memoirs, hearsay, and legend.

Documents have surfaced recently revealing Rasputin's birth date as January 10, 1869.[1] He was assassinated on December 16, 1916, by a group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Yusupov. Recent evidence has raised speculation about the possible involvement of British intelligence agents, who saw his influence at court as a threat to continued Russian involvement as an ally in WWI. Rasputin seems to have foreseen his death and left a prophetic letter predicting its consequences.

Biography

Early life

Rasputin was born into a peasant family in the small village of Pokrovskoye, along the Tura River in the Tobolsk guberniya (now Tyumen Oblast) in Siberia. He had two known siblings, a sister named Maria and an older brother named Dmitri. Maria, said to have been epileptic, was drowned in a river. Dmitri later died of pneumonia after he fell in a pond and Grigori jumped in to save him. The fatalities affected Rasputin, and he subsequently named his two children Maria and Dmitri.

Rasputin reportedly showed indications of supernatural powers throughout his childhood. For example, he mysteriously identified the man who had stolen one of his father's horses and developed a reputation for having a knack for identifying thieves.

When he was around the age of 18, he spent three months in the Verkhoturye Monastery, possibly a penance for theft. His experience there, combined with a reported vision of the Virgin Mary on his return, turned him toward the life of a religious mystic and wanderer. Shortly after leaving the monastery, Rasputin met a holy man, or starets, named Makariy, whose hut was nearby. Makariy had a major influence on him and became a model for Rasputin's spirituality and demeanor.

Rasputin married Praskovia Fyodorovna Dubrovina in 1889, and they had three children, named Dmitri, Varvara, and Maria. Rasputin also reportedly had a child with another woman. In 1901, he left his home in Pokrovskoye as a pilgrim and traveled widely, mostly on foot. He even traveled to Greece, where he visited the holy monks at Mount Athos, and Jerusalem.

Rasputin also encountered the banned Christian sect known as the Khlysty (flagellants), whose impassioned services, ending in physical exhaustion, were infamous, spawning widespread rumors that religious and sexual ecstasy were combined in these rituals. Suspicions that Rasputin was one of the Khlysts threatened his reputation until the end of his life. According to Rasputin's daughter, Maria, Rasputin did "look into" the Khlysty sect, but rejected it.[2]

In 1903, Rasputin arrived in Saint Petersburg, where he gradually gained a reputation as a starets (holy man) with healing and prophetical powers.

Healer to the Tsarevich

In 1905, Rasputin was approached to help the Tsarevich Alexei, who suffered from a serous case of hemophilia. Through his prayers and healing presence, he was indeed able to give the Tsarevich relief, in spite of the doctors' prediction that the boy would die. Numerous reports indicate that whenever the boy had an injury which caused him internal or external bleeding, the Tsaritsa called on Rasputin, and the Tsarevich subsequently got better. The family soon developed a dependency on Rasputin, and he began to act as its spiritual adviser.

The Tsar referred to Rasputin as "our friend" and a "holy man," a sign of the trust that the family placed in him. Rasputin had a considerable personal and political influence on Alexandra,[3] and both the the Tsar and Tsaritsa considered him a prophet. Eventually, he became a kind of appointment secretary to the royal couple, a situation which caused considerable resentment among the Russian nobility. Alexandra even came to believe that God spoke to her through Rasputin.

Controversy

Rasputin also gathered a circle of followers and admirers in the capital. However, while fascinated by him, the Saint Petersburg elite did not widely accept Rasputin: He did not fit in with the royal family and had had a very tense relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church. The Holy Synod frequently criticized Rasputin, accusing him of a variety of immoral or evil practices. Because Rasputin was a court official, he and his apartment were under 24-hour surveillance.

Like many spiritually-minded Russians, Rasputin spoke of salvation as depending less on the clergy and the church than on seeking the spirit of God within. He also reportedly claimed that, for him, yielding to temptations such as sex and alcohol helped dispel the sin of vanity, and was a necessary step on the road to repentance and salvation.

Rasputin soon became a controversial figure, and was caught up in a sharp political struggle involving monarchist, anti-monarchist, revolutionary, and other political forces and interests. He was considered too friendly with Jews and other religious suspect groups, and was accused by many eminent persons of various misdeeds, ranging from an unrestricted sexual life (including raping a nun)[4] to undue political domination over the royal family.

Rasputin was deeply opposed to war, both from a moral point of view and as something which was likely to lead to political catastrophe. During the years of World War I, Rasputin's increasing drunkenness, sexual promiscuity, and willingness to accept bribes in return for helping petitioners who flocked to his apartment, as well as his efforts to have his critics dismissed from their posts, made him appear both corrupt and cynical. Rasputin became the focus of accusations of unpatriotic influence at court. The unpopular Tsaritsa, meanwhile, was of German descent, and she came to be accused of acting as a spy in German employ.

When Rasputin expressed an interest in going to the front to bless the troops early in the war, the Commander-in-Chief, Grand Duke Nicholas, threatened to hang him if he dared to show up there. Rasputin then claimed that he had a revelation that the Russian armies would not be successful until the Tsar personally took command. With this, the ill-prepared Nicholas proceeded to take personal command of the Russian army, with dire consequences for himself as well as for Russia.

While Tsar Nicholas II was away at the front, Rasputin's influence over Tsaritsa Alexandra increased immensely. He soon became her confidant and personal adviser, and also convinced her to fill some governmental offices with his own handpicked candidates. Meanwhile Russia's economy was declining at a very rapid rate. Many at the time laid the blame on Alexandra and Rasputin, and rumors began to circulate that they were sexually intimate as well.

Rasputin's alleged hold over the royal family was used both against him and the Romanovs by politicians and journalists who sought to weaken the integrity of the dynasty, force the Tsar to give up his absolute political power, and separate the Russian Orthodox Church from the state. Rasputin unintentionally contributed to their propaganda by having public disputes with clergy members, bragging about his ability to influence both the Tsar and Tsaritsa, and also by his dissolute public lifestyle. Nobles in influential positions around the Tsar, as well as some parties of the Duma, clamored for Rasputin's removal from the court.

Assassination

Rasputin survived one assassination attempt and almost survived a second, in which he was reportedly poisoned, shot, and left for dead, shot again when he revived, beaten, and drowned. In June 1914, Rasputin was visiting his wife and children in his hometown of Pokrovskoye. On June 29, he had either just received a telegram or was just exiting church, when he was attacked suddenly by Khionia Guseva, a former prostitute who had become a disciple of the monk Iliodor, once a friend of Rasputin's but now absolutely disgusted with his behavior. Guseva thrust a knife into Rasputin's abdomen, and his entrails hung out of what seemed like a mortal wound. Convinced of her success, Guseva supposedly screamed, "I have killed the Antichrist!" After intensive surgery, however, Rasputin recovered. His daughter stated in her memoirs that he was never the same man after receiving this wound: He tired more easily and frequently took opium for pain.

The murder of Rasputin has become legend, some of it apparently invented by the very men who killed him. It is generally agreed that, on December 16, 1916, having decided that Rasputin's influence over the Tsaritsa had made him a dangerous threat to the empire, a group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Yusupov and the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, apparently lured Rasputin to the Yusupovs' Moika Palace, where they served him cakes and red wine laced with a massive amount of cyanide. According to legend, Rasputin was unaffected, although Vasily Maklakov had supplied enough poison to kill seven men. (However, Maria's account asserts that, if her father did eat or drink poison, it was not in the cakes or wine, because, after the attack by Guseva, he had hyperacidity, and avoided anything with sugar. She expressed doubt that he was poisoned at all.)

Determined to finish the job, Yusupov became anxious about the possibility that Rasputin might live until the morning, which would leave the conspirators with no time to conceal his body. Yusupov ran upstairs to consult the others and then came back down to shoot Rasputin through the back with a revolver. Rasputin fell, and the company left the palace.

However, Yusupov decided to return to get his coat. He also decided to check on the body. When he did so, Rasputin opened his eyes, grabbed Yusupov by the throat and strangled him. "You bad boy," Rasputin whispered ominously in his ear, before throwing him across the room and escaping. As he made his bid for freedom, however, the other conspirators arrived and fired at him. After being hit three times in the back, Rasputin fell once more. As they neared his body, the party found that, remarkably, he was still alive, struggling to get up. They clubbed him into submission and, after wrapping his body in a sheet, threw him into an icy river, where he finally met his end—as had both his siblings before him.

Three days later, the body of Rasputin, shot four times and badly beaten, was recovered from the Neva River and autopsied. The cause of death, however, was declared to be hypothermia. His arms were found in an upright position, as if he had tried to claw his way out from under the ice. In the autopsy, it was reportedly found that he had indeed been poisoned, and that the poison alone should have been enough to kill him. However, later investigations have contradicted this.

Subsequently, the Empress Alexandra buried Rasputin's body in the grounds of Tsarskoye Selo. However, after the February Revolution, a group of workers from Saint Petersburg uncovered the remains, carried them into a nearby wood and burned them.

Recent evidence

The details of the assassination given by Felix Yusupov have never stood up to close examination. He told many versions of his story: The statement which he gave to the Saint Petersburg Police on December 16, 1916, the account that he gave while in exile in the Crimea in 1917, his 1927 book, and the accounts given under oath to libel juries in 1934 and 1965. No two accounts were entirely identical, and, until recently, no other credible, evidence-based theories have been available.

However, the unpublished 1916 autopsy report, as well as subsequent reviews of the report by Dr. Vladimir Zharov in 1993, and Professor Derrick Pounder in 2004/05, reveal that—contrary to earlier reports—no active poison was found in Rasputin's body. All three sources agree that Rasputin had been shot, systematically beaten, and attacked with a bladed weapon. However, there were discrepancies between the autopsy and the statements of the supposed killers regarding the number and caliber of handguns used.

This discovery may have significantly changed the whole premise and account of Rasputin's death. The involvement of British intelligence agents in the murder has been suggested, both on the basis of an apparent cover-up, and relating to the fact that the British suspected Rasputin as undermining British interests at the Tsar's court, especially regarding Russia's continued involvement as a British ally in WWI.

Legacy

Rasputin's daughter, Maria Rasputin (1898–1977), emigrated to France after the October Revolution, and then to the U.S. There, she worked as a dancer and then a tiger-trainer in a circus. She left memoirs[5] about her father, wherein she painted an almost saintly picture of him, insisting that most of the negative stories were based on slander and the misinterpretations of facts by his enemies.

Mere weeks before he was assassinated, according to his secretary Simonovich, Rasputin wrote the following remarkable letter:

I write and leave behind me this letter at St. Petersburg. I feel that I shall leave life before January 1… If I am killed by common assassins, and especially by my brothers the Russian peasants, you, Tsar of Russia, will have nothing to fear for your children, they will reign for hundreds of years in Russia. But if I am murdered by boyars, nobles, and if they shed my blood, their hands will remain soiled with my blood, for twenty-five years they will not wash their hands from my blood. They will leave Russia. Brothers will kill brothers, and they will kill each other and hate each other, and for 25 years there will be no nobles in the country. Tsar of the land of Russia, if you hear the sound of the bell which will tell you that Grigori has been killed, you must know this: If it was your relations who have wrought my death, then no one in the family, that is to say, none of your children or relations, will remain alive for more than two years. They will be killed by the Russian people…—Grigori

The contemporary press, as well as sensationalist articles and books published in the 1920s and 1930s, turned the charismatic peasant into a twentieth century legend. To Westerners, Rasputin came to be the embodiment of the stereotypes attributed to the Russian people in those times, backwardness, superstition, irrationality, and licentiousness. To some Russians, especially the Communists, he represented all that was evil in the old regime, which needed to be overcome by the Revolution. To others, Rasputin remained a symbol of the voice of the peasantry, and many to this day reject the negative stories and honor the man. A movement even exists to seek the canonization of Rasputin, but this has been condemned by the Moscow Patriarchate.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T. Rasputin: A Life. Praeger Publishers, 1989. ISBN 978-027593215X

- King, George. The Last Empress: The Life and Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, Tsarina of Russia. Replica Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0735101043

- Levine, Alan. A Lexicon of Lunacy: Metaphoric Malady, Moral Responsibility, and Psychiatry. Transaction Publisher, 2003. ISBN 978-0765805065

- Radzinsky, Edvard. Rasputin: The Last Word. London, 2000.

- Radzinsky, Edvard. The Rasputin File. Anchor, 2001. ISBN 978-0385489102

- Rasputina, Matrena. Memoirs of The Daughter.Moscow, 2001. ISBN 5-8159-0180-6. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

External links

All links retrieved July 17, 2017.

- The Alexander Palace Time Machine Bios-Rasputin - bio of Rasputin. www.alexanderpalace.org.

- Okhrana Surveillance Report on Rasputin - from the Soviet Krasnyi Arkiv.

- The Murder of Rasputin. ThoughtCo.com.

- Rasputin the Musical by Michael Rapp. www.rasputinthemusical.com.

- BBC's Rasputin murder reconstruction. www.bbc.co.uk.

- RASPUTIN Grigory Efimovich. www.encspb.ru.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.