Hemophilia, or haemophilia, is the name of any of several hereditary genetic illnesses that impair the body's ability to control bleeding.

Genetic deficiencies (or, very rarely, an autoimmune disorder) cause lowered activity of the plasma clotting factor, which thus compromises the clotting of blood-clotting so that when a blood vessel is injured, a scab will not form and the vessel will continue to bleed excessively for a long time. The bleeding can be external, if the skin is broken by a scrape, cut, or abrasion, or it can be internal, with blood leaking into muscles, joints, or hollow organs. Bleeding, therefore, may present itself either visibly as skin bruises or subtly as melena (blood in the feces), hematuria (blood in the urine), or bleeding in the brain, which can be fatal. In subtler cases, bleeding may be present only following major procedures in newborn babies and then may be injury related in the toddler period and onwards.

Though there is no cure for hemophilia, many treatments have been discovered and made available to control the disease. The processes of treating the disease and containing its transmission both call for the exercise of personal and family responsibility to assure the best treatment of the patient and reduction of the likelihood of transmitting the disease to future generations.

History

The first record of hemophilia is the Jewish holy text, Talmud, which states that males did not have to be circumcised if two brothers had already died from the procedure. In the twelfth century, the Arab physician Albucasis wrote of a family whose males died of bleeding after minor injuries. Then, in 1803, Dr. John Conrad Otto, a Philadelphia physician, wrote an account about "a hemorrhagic disposition existing in certain families." He recognized that the disorder was hereditary and that it affected males and rarely females. He was able to trace the disease back to a woman who settled near Plymouth in 1720.

The first usage of the term "haemophilia" appears in a description of the condition written by Hopff at the University of Zurich in 1828. In 1937, Patek and Taylor, two doctors from Harvard, discovered Factor VII, an anti-hemophilic globulin. Pavlosky, a doctor from Buenos Aires, found Hemophilia A and Hemophilia B to be separate diseases by doing a lab test. This test was done by transferring the blood of one hemophiliac to another hemophiliac. The fact that this corrected the clotting problem showed that there was more than one form of hemophilia.

Hemophilia figured prominently in the history of European royalty and thus is sometimes known as "the royal disease." Queen Victoria, of the United Kingdom, passed the mutation to her son Leopold and, through several of her daughters, to various royals across the continent, including the royal families of Spain (House of Bourbon), Germany (Hohenzollern), and Russia (Romanov). Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich of Russia, son of Nicholas II, was a descendant of Queen Victoria and suffered from hemophilia.

Forms

Different types of hemophilia exist. These forms of hemophilia are diagnosed depending on the specific factor deficiency. Factors are substances that function in certain bodily processes. In this case, they aid and are necessary for blood coagulation.

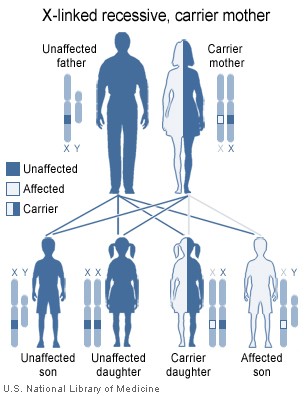

Different types of hemophilia also have different genetic tendencies. For instance, Hemophilia A and B are X-linked recessive, meaning that males are more commonly affected by the illnesses. For a woman to be affected, her mother and father would both have to carry the gene in order for the woman to be affected by a recessive disorder. This is unlikely if compared to the scenario for men, in which only one parent has to be a carrier of the gene and pass on to male offspring (men have XY chromosome pair as compared to women who are XX). X-linked recessive suffers carry the gene on all of their X chromosomes (discussed in following section).

- Hemophilia A—factor VIII deficiency, "classic hemophilia" (X-linked recessive)

- Hemophilia B—factor IX deficiency, "Christmas disease" (X-linked recessive)

- Hemophilia C—factor XI deficiency (Ashkenazi Jews, autosomal recessive)

Hemophilia C differs from the other types in many ways. First, it can be transmitted to either males or females with equal ratios, as it is autosomal recessive. Secondly, it commonly does not cause bleeding into muscles and joints as the other types do. Also, in comparison to Hemophilia A, it has a ten times less common prevalence in the United States.

The unrelated type 1 and type 2 von Willebrand disease (vWD) are milder than any of the three hemophilias; only type 3 von Willebrand disease expresses a severity similar to the hemophilias. vWD is caused by mutations in the coagulation protein von Willebrand factor, therefore indirectly preventing the utilization of factor VIII and the subsequent coagulation problems. This occurs as von Willebrand factor is a carrier protein for factor VIII. It is the most common coagulation disorder present in 1 percent of the population.

Genetics

Females possess two X-chromosomes, whereas males have one X and one Y chromosome. Since the mutations causing the disease are recessive, a woman carrying the defect on one of her X-chromosomes may not be affected by it, as the equivalent allele on her other chromosome should express itself to produce the necessary clotting factors. However the Y-chromosome in men has no gene for factors VIII or IX. If the genes responsible for production of factor VIII or factor IX present on a male's X-chromosome are deficient, there are no equivalent genes on the Y-chromosome. Hence, the deficient gene is not masked by the autosomal dominant allele and he will develop the illness.

Since a male receives his single X-chromosome from his mother, the son of a healthy female silently carrying the deficient gene will have a 50 percent chance of inheriting that gene from her and with it the disease; and if his mother is affected with hemophilia, he will have a 100 percent chance of being a hemophiliac. In contrast, for a female to inherit the disease, she must receive two deficient X-chromosomes, one from her mother and the other from her father (who must therefore be a hemophiliac himself). Hence, hemophilia is far more common among males than females. However it is possible for female carriers to become mild hemophiliacs due to lyonisation of the X chromosomes. Lyonisation refers to random inactivation of an X-chromosome in the cells of females. Hemophiliac daughters are more common than they once were, as improved treatments for the disease have allowed more hemophiliac males to survive to adulthood and become parents. Adult females may experience menorrhagia (heavy periods) due to the bleeding tendency.

As with all genetic disorders, it is of course also possible for a human to acquire it spontaneously (de novo), rather than inheriting it, because of a new mutation in one of their parents' gametes (specialized haploid cell involved in sexual reproduction). Spontaneous mutations account for about 1/3 of all Hemophilia A and 1/5 of all Hemophilia B cases.

Genetic testing and genetic counseling are recommended for families with hemophilia. Prenatal testing, such as amniocentesis, is available to pregnant women who may be carriers of the condition.

Probability

If a woman gives birth to a hemophiliac child, she is a carrier for the disease. Until modern direct DNA testing, however, it was impossible to determine if a female with only healthy children was a carrier or not. Generally, the more healthy sons she bore, the higher the probability that she was not a carrier.

According to Baxter Healthcare Corporation, a global health care company, in 2006 about 13,500 people in the United States suffer from Hemophilia A. That translates to one in every five thousand people. Hemophilia B affects one out of every 30,000 Americans, which is roughly three thousand people. Von Willebrand disease is more common and is prevalent in one out of every one hundred persons. It affects up to two million people in the United States.

Treatment

Though there is no cure for hemophilia, it can be controlled with local management of the wound as well as regular injections of the deficient clotting factor, i.e. factor VIII in Hemophilia A or factor IX in Hemophilia B. Some hemophiliacs develop antibodies (inhibitors) against the replacement factors given to them, so the amount of the factor has to be increased or non-human replacement products must be given, such as porcine factor VIII. Also, tranexamic acid can be used prophylactically before known procedures and as an adjunct given, which allows for a lower required dose of the specific clotting factor.

If a patient becomes refractory to replacement coagulation factor as a result of circulating inhibitors, this may be overcome with recombinant human factor VII (NovoSeven®), which is registered for this indication in many countries.

In western countries, common standards of care fall into one of two categories: Prophylaxis or on-demand. Prophylaxis involves the infusion of clotting factor on a regular schedule in order to keep clotting levels sufficiently high to prevent spontaneous bleeding episodes. On-demand treatment involves treating bleeding episodes once they arise.

As a direct result of the contamination of the blood supply in the late 1970s and early/mid 1980s with viruses such as hepatitis and HIV, new methods were developed in the production of clotting factor products. The initial response was to heat treat (pasteurize) plasma-derived factor concentrate, followed by the development of monoclonal factor concentrates. These concentrates use a combination of heat treatment and affinity chromatography to inactivate any viral agents in the pooled plasma from which the factor concentrate is derived.

Since 1992, recombinant factor products (which are typically cultured in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) tissue culture cells and involve little, if any human plasma products) have become available and are widely used in wealthier western countries. While recombinant clotting factor products offer higher purity and safety, they are, like concentrate, extremely expensive and not generally available in the developing world. In many cases, factor products of any sort are difficult to obtain in developing countries.

With a better, modern understanding of transmission of the disease process, patients suffering from this condition are genetically counseled to increase awareness of transmission of the condition and its associated complications.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Bleeding Disorders Overview: A Quick Comparison of Selected Bleeding Disorders. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Geil, J. D. 2006. Von Willebrand Disease. WebMD. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Prasad, M. 2006. Hemophilia C. WebMD. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Sawaf, H. 2006. Hemophilia A and B. WebMD. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Silverthorn, D. 2004. Human Physiology, An Integrated Approach (3rd Edition). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 013102153

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.