Hasekura Tsunenaga

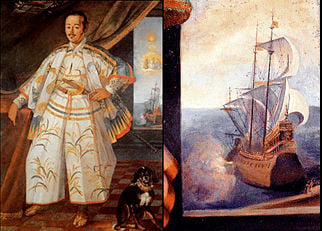

| Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga (1571–1622)  Hasekura's portrait during his mission in Rome in 1615, by Claude Deruet, Coll. Borghese, Rome | ||

| Names: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Japanese name: | Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga (支倉六右衛門常長) | |

| Christian name: | Don Felipe Francisco Hasekura | |

| Retainer of: | ||

| Overlord: | Date Masamune | |

| Fief: | Sendai Domain (仙台藩) (Northeastern Japan) | |

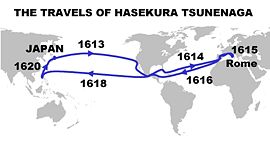

Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga (1571 – 1622) (Japanese: 支倉六右衛門常長, also spelled Faxecura Rocuyemon in period European sources, reflecting the contemporary pronunciation of Japanese)[1] was a Japanese samurai and retainer of Date Masamune, the daimyo of Sendai. From 1613 through 1620, Hasekura headed a diplomatic mission, known as the Keichō Embassy, (慶長使節).[2] to the Vatican in Rome, traveling through New Spain (arriving in Acapulco and departing from Veracruz) and visiting various ports-of-call in Europe. Hasekura met the King of Spain and Pope Paul V, and delivered letters from his daimyo, Date Masamune, seeking trade with Spain and inviting Catholic missionaries to Japan. On the return trip, Hasekura and his companions re-traced their route across Mexico in 1619, sailing from Acapulco for Manila, and then sailing north to Japan in 1620.[3] This is considered to be the first Japanese embassy to the Americas and Europe.[4]

Although Hasekura's embassy was cordially received in Europe, during his stay there, the Japanese Shogunate began its suppression of Christianity and its sakoku policy of national isolation. Two days after receiving Hasekura’s report of his mission, Date Masamune issued an edict prohibiting Christianity in his territories. Hasekura’s descendants were eventually executed for being Christian, and his voyage was forgotten until 1873, when a Japanese embassy to Europe was shown the official records of it. Hasekura and his Japanese entourage attracted considerable attention wherever they went, and numerous journals, church records and historical documents in Mexico and Europe contain descriptions of them.

Early life

Little is known of the early life of Hasekura Tsunenaga. He was a mid-level noble samurai in the Sendai Domain in northern Japan, in the service of the daimyo Date Masamune. They were of roughly the same age, and it is recorded that Tsunenaga acted as Date’s representative on several important occasions..

It is also recorded that, for six months in 1597, Hasekura served as a samurai in the Japanese invasion of Korea under Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

In 1612, Hasekura's father, Hasekura Tsunenari (支倉常成), was indicted for corruption, and he was put to death in 1613. His fief was confiscated, and his son should ordinarily have been executed with him. Date, however, gave him the opportunity to redeem his honor by placing him in charge of the embassy to Europe, and soon returned his territories to him.

Background: early contacts between Japan and Spain

The Spanish started trans-Pacific voyages between New Spain (Mexico) and the Philippines in 1565. The famous Manila galleons carried silver from Mexican mines westward to the entrepôt of Manila in the Spanish possession of the Philippines. There, the silver was used to purchase spices and trade goods gathered from throughout Asia, including (until 1638) goods from Japan. The return route of the Manila galleons, first charted by the Basque navigator Andrés de Urdaneta, took the ships northeast into the Kuroshio Current (also known as the Japan Current) off the coast of Japan, and then across the Pacific to the west coast of North America, landing eventually in Acapulco.[5]

Spanish ships were periodically shipwrecked on the coasts of Japan due to bad weather, initiating contact between Spain and Japan. Spain’s efforts to expand its influence in Japan were met by stiff resistance from the Jesuits, who had started evangelizing there in 1549, as well as the Portuguese and the Dutch who did not want Spain to participate in Japanese trade. However, some Japanese, such as Christopher and Cosmas, are known to have crossed the Pacific onboard Spanish galleons as early as 1587. It is known that gifts were exchanged between the governor of the Philippines and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who thanked him in a letter dated 1597, writing "The black elephant in particular I found most unusual."[6]

In 1609, the Spanish Manila galleon San Francisco encountered bad weather on its way from Manila to Acapulco, and was wrecked on the Japanese coast in Chiba, near Tokyo. The sailors were rescued and welcomed, and the ship's captain, Rodrigo de Vivero, former interim governor of the Philippines, met with the retired shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. Rodrigo de Vivero drafted a treaty, signed on November 29, 1609, allowing for the Spaniards to establish a factory in eastern Japan, mining specialists to be imported from New Spain, Spanish ships to visit Japan in case of necessity, and a Japanese embassy to be sent to the Spanish court.

First Japanese expeditions to the Americas

1610 San Buena Ventura

A Franciscan monk named Luis Sotelo, who was proselytizing in the area of Tokyo, convinced Tokugawa Ieyasu and his son Tokugawa Hidetada to send him as a representative to New Spain (Mexico) on one of their ships, in order to advance the trade treaty. Rodrigo de Vivero offered to sail on the Japanese ship in order to guarantee the safety of their reception in New Spain, but insisted that another Franciscan, named Alonso Muños, be sent instead as the Shogun's representative. In 1610, Rodrigo de Vivero, several Spanish sailors, the Franciscan father, and 22 Japanese representatives led by the trader Tanaka Shosuke, sailed to Mexico aboard the San Buena Ventura, a ship built by the English adventurer William Adams for the Shogun. Once in New Spain, Alonso Muños met with the Viceroy Luis de Velasco, who agreed to send the explorer Sebastian Vizcaino aa ambassador to Japan, with the added mission of exploring the "Gold and silver islands" ("Isla de Plata") that were thought to be east of the Japanese isles.

Vizcaino arrived in Japan in 1611, and met many times with the Shogun and feudal lords. His lack of respect for Japanese customs, the mounting resistance of the Japanese towards Catholic proselytism, and the intrigues of the Dutch against Spanish ambitions made these meetings ineffectual. Vizcaino finally left to search for the "Silver island," encountered bad weather, and returned to Japan with his ships heavily damaged.

1612 San Sebastian

Without waiting for Vizcaino, another ship – built in Izu by the Bakufu under the minister of the Navy Mukai Shogen, and named San Sebastian, left for Mexico on September 9, 1612, carrying Luis Sotelo and two representatives of Date Masamune, with the objective of advancing the trade agreement with New Spain. However, the ship foundered a few miles from Uraga, and the expedition had to be abandoned.

The 1613 embassy

The Shogun decided to build a new galleon in Japan to take Vizcaino back to New Spain, together with a Japanese embassy accompanied by Luis Sotelo. The galleon, named Date Maru by the Japanese and later San Juan Bautista by the Spanish, was built in 45 days, with the participation of technical experts from the Bakufu (the Minister of the Navy Mukai Shogen, an acquaintance of William Adams with whom he built several ships, dispatched his Chief Carpenter), 800 shipwrights, 700 smiths, and 3000 carpenters. The daimyo of Sendai, Date Masamune, was put in charge of the project, and named one of his retainers, Hasekura Tsunenaga (his fief was rated at around 600 koku), to lead the mission:

"The Great Ship left Toshima-Tsukinoura for the Southern Barbarians on September 15th [Japanese calendar], with at its head Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga, and those called Imaizumi Sakan, Matsuki Shusaku, Nishi Kyusuke, Tanaka Taroemon, Naito Hanjuro, Sonohoka Kyuemon, Kuranojo, Tonomo, Kitsunai, Kyuji, as well as several others under Rokuemon, as well as 40 Southern Barbarians, 10 men of Mukai Shogen, and also tradespeople, to a total 180" (Records of the Date House, Keichō-Genna 伊達家慶長元和留控, Gonoi, 56).

The objective of the Japanese embassy was both to discuss trade agreements with the Spanish crown in Madrid, and to meet with the Pope in Rome. Date Masamune displayed a great willingness to welcome the Catholic religion in his domain: he invited Luis Sotelo and authorized the propagation of Christianity in 1611. In his letter to the Pope, brought by Hasekura, he wrote: "I'll offer my land for a base of your missionary work. Send us as many padres as possible."

Sotelo’s account of the voyage emphasizes the religious dimension of the mission, claiming that its main objective was to spread the Christian faith in northern Japan:

"I was formerly dispatched as ambassador of Idate Masamune, who holds the reins of the kingdom of Oxu [Japanese:奥州] (which is in the Eastern part of Japan)—who, while he has not yet been reborn through baptism, has been catechized, and was desirous that the Christian faith should be preached in his kingdom—together with another noble of his Court, Philippus Franciscus Faxecura Rocuyemon, to the Roman Senate & to the one who at that time was in charge of the Apostolic See, His Holiness Pope Paul V." (Luis Sotelo De Ecclesiae Iaponicae Statu Relatio, 1634).[7]

The embassy was probably part of a plan to diversify and increase trade with foreign countries, before the participation of Christians in the Osaka rebellion caused the Shogunate to prohibit Christianity in the territories it directly controlled, in 1614.

Trans-Pacific voyage

The Date Maru ship left on October, 28, 1613 for Acapulco, with around 180 people on board, including ten samurai of the Shogun (provided by the Minister of the Navy Mukai Shogen Tadakatsu), 12 samurai from Sendai, 120 Japanese merchants, sailors, and servants, and around 40 Spaniards and Portuguese, including Sebastian Vizcaino who, in his own words, only had the status of a passenger.[8]

New Spain (Acapulco)

The ship first reached Cape Mendocino in today's California, and then continued along the coast to arrive in Acapulco on January 25, 1614, after three months at sea. The Japanese were received with great ceremony, but had to wait in Acapulco until they received orders regarding the rest of their travels.

Fights erupted between the Japanese and the Spaniards, especially Vizcaino, apparently over the handling of presents from the Japanese ruler. A contemporary journal, written by the historian Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin, a noble Aztec born in Amecameca (ancient Chalco province) in 1579, whose formal name was Domingo Francisco de San Anton Muñon, relates that Vizcaino was seriously wounded in the fight:

"Senor Vizcaino is still coming slowly, coming hurt; the Japanese injured him when they beat and stabbed him in Acapulco, as became known here in Mexico, because of all the things coming along that had been made his responsibility in Japan"[9]

Following these fights, orders were promulgated on March 4th and March 5th to restore peace. The orders explained that:

"The Japanese should not be submitted to attacks in this Land, but they should remit their weapons until their departure, except for Hasekura Tsunenaga and eight of his retinue…. The Japanese will be free to go where they want, and should be treated properly. They should not be abused in words or actions. They will be free to sell their goods. These orders have been promulgated to the Spanish, the Indians, the Mulattos, the Mestizos, and the Blacks, and those who don't respect them will be punished".[10]

New Spain (Mexico)

The embassy remained two months in Acapulco and on March 24, 1614, entered Mexico City,[11] where it was received with great ceremony. The embassy spent some time in Mexico, and then went to Veracruz to board the fleet of Don Antonio Oquendo and continue its mission to Europe.

Chimalpahin gives some account of the visit of Hasekura.

"This is the second time that the Japanese have landed one of their ships on the shore at Acapulco. They are transporting here all things of iron, and writing desks, and some cloth that they are to sell here." (Chimalpahin, "Annals of His Time").[12]

- "It became known here in Mexico and was said that the reason their ruler the Emperor of Japan sent this said lordly emissary and ambassador here, is to go in Rome to see the Holy Father Paul V, and to give him their obedience concerning the holy church, so that all the Japanase want to become Christians" (Chimalpahin, "Annals of His Time").[13]

Hasekura was settled in a house next to the Church of San Francisco, and met with the Viceroy. He explained to him that he was also planning to meet King Philip III to offer him peace and to obtain permission for the Japanese to come to Mexico for trade. On Wednesday, April 9, 1614, 20 Japanese were baptized, and 22 more on April 20, by the archbishop in Mexico, don Juan Pérez de la Serna, at the Church of San Francisco. Altogether, 63 of them received confirmation on April 25. Hasekura waited for his travel to Europe to be baptized there:

"But the lordly emissary, the ambassador, did not want to be baptized here; it was said that he will be baptized later in Spain" (Chimalpahin, "Annals of His Time").[14]

Departure for Europe

The embassy left for Europe on the San Jose on June 10, 1614. Hasekura had to leave the largest part of the Japanese group behind, to wait in Acapulco for the return of the embassy.

Chimalpahin explains that Hasekura left some of his compatriots behind before leaving for Europe:

"The Ambassador of Japan set out and left for Spain. In going he divided his vassals; he took a certain number of Japanese, and he left an equal number here as merchants to trade and sell things." (Chimalpahin, "Annals of His Time").[15]

Some of them, as well as those from the previous voyage of Tanaka Shosuke, returned to Japan the same year, sailing back with the San Juan Bautista:

"Today, Tuesday the 14th of the month of October of the year 1614, was when some Japanese set out from Mexico here going home to Japan.; they lived here in Mexico for four years. Some still remained here; they earn a living trading and selling here the goods they brought with them from Japan." (Chimalpahin, "Annals of His Time").[16]

Cuba

The embassy stopped and changed ships in Havana in Cuba in July, 1614. A bronze statue commemorating this event was erected on April 26, 2001, at the head of Havana Bay.

Mission to Europe

Spain

The fleet arrived in Sanlucar de Barrameda on October 5, 1614.

"The fleet arrived safely finally, after some dangers and storms, to the port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda on the 5th of October, where the Duke of Medina Sidonia was advised of the arrival. He sent carriages to honor them and accommodate the Ambassador and his gentlemen" (Scipione Amati "History of the Kingdom of Voxu").[17]

"The Japanese ambassador Hasekura Rokuemon, sent by Joate Masamune, king of Boju, entered Seville on Wednesday, 23 October 1614. He was accompanied by 30 Japanese with blades, their captain of the guard, and 12 bowmen and halberdiers with painted lances and blades of ceremony. The captain of the guard was Christian and was called Don Thomas, the son of a Japanese martyr. He has come to give his obediences to His Holiness on behalf of his king and queen, who have been baptized. All of them had rosaries around their necks; he has come to receive baptism from the hand of the Pope…." (Library Capitular Calombina 84-7-19 Memorias..., fol.195).[18]

The Japanese embassy met with King Philip III in Madrid on January 30, 1615. Hasekura remitted to the King a letter from Date Masamune, as well as an offer for a treaty. The King responded that he would do what he could to accommodate these requests.

Hasekura was baptized on February 17 by the king's personal chaplain, and renamed Felipe Francisco Hasekura. The baptism ceremony was to have been conducted by the Archbishop of Toledo, though he was too ill to actually carry this out, and the Duke of Lerma – the main administrator of Phillip III's rule and the de facto ruler of Spain – was designated as Hasekura's godfather.

The embassy stayed eight months in Spain before leaving the country for Italy.

France

After traveling across Spain, the embassy sailed on the Mediterranean Sea aboard three Spanish frigates towards Italy. Due to bad weather, they had to stay for a few days in the French harbour of Saint-Tropez, where they were received by the local nobility, and made quite a sensation with the populace.

The visit of the Japanese Embassy is recorded in the city's chronicles as led by "Philip Francis Faxicura, Ambassador to the Pope, from Date Masamunni, King of Woxu in Japan."

Many picturesque details of their movements were recorded:

- "They never touch food with their fingers, but instead use two small sticks that they hold with three fingers."

- "They blow their noses in soft silky papers the size of a hand, which they never use twice, so that they throw them on the ground after usage, and they were delighted to see our people around them precipitate themselves to pick them up."

- "Their swords cut so well that they can cut a soft paper just by putting it on the edge and by blowing on it."

- ("Relations of Mme de St Troppez," October 1615, Bibliotheque Inguimbertine, Carpentras).[19]

The visit of Hasekura Tsunenaga to Saint-Tropez in 1615 is the first recorded instance of Franco-Japanese relations.

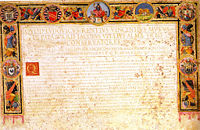

Italy

The Japanese Embassy went on to Italy where they were able to meet with Pope Paul V in Rome in November, 1615, the same year Galileo Galilei was first confronted by the Roman Inquisition regarding his findings against geocentricism. Hasekura remitted to the Pope two gilded letters, one in Japanese and one in Latin, containing a request for a trade treaty between Japan and Mexico and the dispatch of Christian missionaries to Japan. These letters are still visible in the Vatican archives. The Latin letter, probably written by Luis Sotelo for Date Masamune, reads, in part:

- Kissing the Holy feet of the Great, Universal, Most Holy Lord of The Entire World, Pope Paul, in profound submission and reverence, I, Idate Masamune, King of Wôshû in the Empire of Japan, suppliantly say:

- The Franciscan Padre Luis Sotelo came to our country to spread the faith of God. On that occasion, I learnt about this faith and desired to become a Christian, but I still haven't accomplished this desire due to some small issues. However, in order to encourage my subjects to become Christians, I wish that you send missionaries of the Franciscan church. I guarantee that you will be able to build a church and that your missionaries will be protected. I also wish that you select and send a bishop as well. Because of that, I have sent one of my samurai, Hasekura Rokuemon, as my representative to accompany Luis Sotelo across the seas to Rome, to give you a stamp of obedience and to kiss your feet. Further, as our country and Nueva España are neighbouring countries, could you intervene so that we can discuss with the King of Spain, for the benefit of dispatching missionaries across the seas." Translation of the Latin letter of Date Masamune to the Pope.[20]

The Pope agreed to the dispatch of missionaries, but left the decision for trade to the King of Spain.

The Roman Senate also gave to Hasekura the honorary title of Roman Citizen, in a document he brought back to Japan, and which is preserved today in Sendai.

Sotelo also described the visit to the Pope, book De ecclesiae Iaponicae statu relatio (published posthumously in 1634):

- "When we got there by the aid of God in the Year of Our Salvation 1615, not only were we kindly received by His Holiness the great Pope, with the Holy College of the Cardinals and a gathering of bishops and nobles, and even the joy and general happiness of the Roman People, but we and three others (whom the Japanese Christians had specially designated to announce their condition with respect to the Christian religion) were heard, rested, and just as we were hoping, dispatched as quickly as possible." (Sotelo, De ecclesiae Iaponicae statu relatio).[21]

Rumors of political intrigue

Besides the official description of Hasekura's visit to Rome, some contemporary communications indicate that political matters were also discussed, and that an alliance with Date Masamune was suggested as a way to establish Christian influence in the whole of Japan:

- "The Ambassador strongly insisted that the authority and power of his ruler was superior to that of many European countries" (Anonymous Roman communication, dated October 10, 1615)

- "The Franciscan Spanish fathers are explaining that the King of the Ambassador [Hasekura Tsunenaga] will soon become the supreme ruler of his country, and that, not only will they become Christians and follow the will of the church of Rome, but they will also in turn convert the rest of the population. This is why they are requesting the dispatch of a high eclesiastic together with the missionaries. Because of this, many people have been doubting the true purpose of the embassy, and are wondering if they are not looking for some other benefit." (Letter of the Venetian ambassador, November 7, 1615).

Second visit to Spain

On his return to Spain, Hasekura met again with the King, who declined to sign a trade agreement, on the ground that the Japanese Embassy did not appear to be an official embassy from the ruler of Japan Tokugawa Ieyasu, who, on the contrary, had promulgated an edict in January 1614 ordering the expulsion of all missionaries from Japan, and started the persecution of the Christian faith in Japan.

The embassy left Seville for Mexico in June 1617 after a period of two years spent in Europe. Some of the Japanese remained in Spain in a town near Seville (Coria del Río), where their descendants to this day still use the surname Japón.

Western publications on Hasekura's embassy

The embassy of Hasekura Tsunenaga was the subject of numerous publications throughout Europe. The Italian writer Scipione Amati, who accompanied the embassy in 1615 and 1616, published in 1615 in Rome a book titled "History of the Kingdom of Voxu." This book was translated into German in 1617. In 1616, the French publisher Abraham Savgrain published an account of Hasekura's visit to Rome: "Récit de l'entrée solemnelle et remarquable faite à Rome, par Dom Philippe Francois Faxicura" ("Account of the solemn and remarquable entrance in Rome of Dom Philippe Francois Faxicura").

Return to Mexico

Hasekura stayed in Mexico for five months on his way back to Japan. The San Juan Bautista had been waiting in Acapulco since 1616, after a second trip across the Pacific from Japan to Mexico. Captained by Yokozawa Shogen, she was laden with fine pepper and lacquerware from Kyoto, which were sold on the Mexican market. Following a request by the Spanish king, in order to avoid too much silver leaving Mexico for Japan, the Viceroy asked for the proceeds to be spent on Mexican goods, except for an amount of 12,000 pesos and 8,000 pesos in silver which Hasekura and Yokozawa could bring back with them respectively.

Philippines

In April, 1618, the San Juan Bautista arrived in the Philippines from Mexico, with Hasekura and Luis Sotelo on board. The ship was acquired by the Spanish government there, for use in building up defenses against the attacks of the Dutch and the English. The bishop of the Philippines with the local Filipinos and native Tagalog in Manila described the deal to the king of Spain in a missive dated July 28, 1619:

- "The Governor was extremely friendly with the Japanese, and provided them with his protection. As they had many expensive things to buy, they decided to lend their ship. The ship was immediately furbished for combat. The Governor eventually bought the ship, because it turned out that it was of excellent and sturdy construction, and available ships were dramatically few. In favor of your Majesty, the price paid was reasonable." (Document 243)

During his stay in the Philippines with local Filipinos and Native Tagalog, Hasekura purchased numerous goods for Date Masamune, and built a ship, as he explained in a letter he wrote to his son. He finally returned to Japan in August 1620, reaching the harbor of Nagasaki.

Return to Japan

By the time Hasekura came back, Japan had changed drastically: an effort to eradicate Christianity had been under way since 1614; Tokugawa Ieyasu had died in 1616 and been replaced by his more xenophobic son Tokugawa Hidetada; and Japan was moving towards the "sakoku" policy of national isolation. News of these persecutions arrived in Europe during Hasekura's embassy, and European rulers – especially the King of Spain – became very reluctant to respond favorably to Hasekura's trade and missionary proposals.

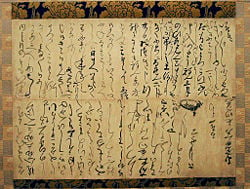

Hasekura reported his travels to Date Masamune upon his arrival in Sendai. It is recorded that he remitted a portrait of Pope Paul V, a portrait of himself in prayer (shown above), and a set of Ceylonese and Indonesian daggers acquired in the Philippines, all preserved today in the Sendai City Museum. The "Records of the House of Masamune" describe his report in a rather succinct manner, ending with a rather cryptic expression of surprise bordering on outrage ("奇怪最多シ") at Hasekura's discourse:

- "Rokuemon went to the country of the Southern Barbarians, he paid his respects to the king Paolo, he stayed there for several years, and now he sailed back from Luzon. He brought paintings of the king of the Southern Barbarians, and a painting of himself, which he remitted. Many of his descriptions of the Southern Barbarian countries, and the meaning of Rokuemon's declarations were surprising and extraordinary."[22]

Interdiction of Christianity in Sendai

The direct effect of Hasekura's return to Sendai was the interdiction of Christianity in the Sendai fief two days later:

- "Two days after the return of Rokuemon to Sendai, a three-point edict against the Christian was promulgated: first, that all Christians were ordered to abandon their faith, in accordance with the rule of the Shogun, and for those who did not, they would be exiled if they were nobles, and killed if they were citizens, peasants or servants. Second, that a reward would be given for the denunciation of hidden Christians. Third that propagators of the Christian faith should leave the Sendai fief, or else, abandon their religion" (November 1620 letter of father Angelis, Japan-China archives of the Jesuits in Rome, quoted in Gonoi's "Hasekura Tsunenaga," 231)

It is not known what Hasekura said or did to bring about such a reaction. Later events indicate that he and his descendants remained faithful Christians; Hasekura may have given an enthusiastic – and disturbing – account of the greatness and might of Western countries and the Christian religion. He may also have encouraged an alliance between the Church and Date Masamune to take over Japan (an idea promoted by the Franciscans while in Rome), Hopes of trade with Spain evaporated when Hasekura communicated that the Spanish King would not enter into an agreement as long as persecutions were occurring in the rest of the country.

Date Masamune, who had been very tolerant of Christianity in spite of the Bakufu's prohibition in the land it directly controlled, suddenly chose to distance himself from the Western faith. The first executions of Christians started 40 days later. The anti-Christian measures taken by Date Masumune were, however, comparatively mild, and Japanese and Western Christians repeatedly claimed that they were only undertaken to appease the Shogun:

- "Date Masumune, out of fear of the Shogun, ordered the persecution of Christianity in his territory, and created several martyrs." (Letter of 17 prominent Japanese Christians from Sendai, to the Pope, 29 September 1621).[23]

One month after Hasekura's return, Date Masamune wrote a letter to the Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada, in which he makes a very clear effort to evade responsibility for the embassy, explaining in detail how it was organized with the approval, and even the collaboration, of the Shogun:

- "When I sent a ship to the Southern Barbarian countries several years ago, upon the advice of Mukai Shogen, I also dispatched the Southern Barbarian named Sotelo, who had resided for several years in Edo. At that time, your highness also gave messages for the Southern Barbarians, as well as presents, such as folding screens and sets of armour." (October 18, 1620, quoted in Gonoi, 234).

Spain, with a colony and an army in the nearby Philippines, was the greatest threat to Japan at that time. Hasekura’s eyewitness accounts of Spanish power and colonial methods in Nueva España (Mexico) may have precipitated the Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada's decision to sever trade relations with Spain in 1623, and diplomatic relations in 1624, although other events such as the smuggling of Spanish priests into Japan and a failed Spanish embassy also contributed to the decision.

Death

Hasekura’s fate is unknown, and there are numerous conflicting accounts of his final years. Contemporary Christian commentators could only rely on hearsay; some rumors claimed that he abandoned Christianity, others that he was martyred for his faith, and others that he practiced Christianity in secret. The fate of his descendants and servants, who were later executed for being Christians, suggests that Hasekura remained strongly Christian himself, and transmitted his faith to the members of his family. Hasekura’s travel companions, such as Yokozawa Shogen are known to have remained faithful Christians even after their return in Japan.[24]

Sotelo, who returned to Japan but was caught and finally burned at the stake in 1624, gave before his execution an account of Hasekura returning to Japan as a hero who propagated the Christian faith, and passed away one year after his return:

"My other colleague, the ambassador Philippus Faxecura, after he reached his aforementioned king (Date Masamune), was greatly honored by him, and sent to his own estate, to rest after such a long and tiring journey, where he made his wife, children, servants, and many other vassals into Christians, and advised other nobles who were his kith and kin to accept the faith, which they indeed did. While he was engaged in these and other pious works, a full year after his return, having provided much instruction and a great example, with much preparation, he piously passed on, leaving for his children by a special inheritance the propagation of the faith in his estate, and the protection of the religious (i.e. "members of religious orders") in that kingdom. The King and all the nobles were greatly saddened by his passing, but especially the Christians and Religious, who knew very well the virtue and religious zeal of this man. This is what I heard by letters from the very Religious who administered the sacraments to him, and who had been present at his death, as well as from others." (Luis Sotelo, De ecclesiae Iaponicae statu relatio).[25]

Hasekura brought several Catholic artifacts back to Japan, but he did not give them to his ruler, and instead kept them in his own estate.

Hasekura Tsunenaga died of illness (according to Japanese as well as Christian sources) in 1622, but the location of his grave is not known for certain. Three graves are claimed as Hasekura's. One is visible in the Buddhist temple of Enfukuji (円長山円福寺) in Miyagi. Another is clearly marked (along with a memorial to Padre Sotelo) in the cemetery of a Buddhist temple in the Kitayama neighborhood, just north of the center of Sendai, located between Shifukuji Temple and Aoba Ginja (Shinto shrine).

Execution of his descendants and servants

Hasekura had a son, named Rokuemon Tsuneyori. Two of his son's servants, Yogoemon (与五右衛門) and his wife, were convicted of being Christian but refused to recant their faith under torture (reverse hanging, tsurushi, 釣殺し) and as a result died in August, 1637. In 1637, Rokuemon Tsuneyori himself also came under suspicion of Christianity after being denounced by someone from Edo, but escaped questioning because he was the master of the Zen temple of Komyoji (光明寺). In 1640, two other servants of Tsuneyori, Tarozaemon (太郎左衛門, 71), who had followed Hasekura to Rome, and his wife (59), were convicted of being Christians, and, also died after refusing to recant their faith under torture. Tsuneyori was held responsible this time, and was decapitated the same day for having failed to denounce Christians under his roof, although it remained unclear whether he was himself Christian or not.[26] Two Christian priests, the Dominican Pedro Vazquez and Joan Bautista Paulo, had given his name under torture. Tsuneyori's younger brother, Tsunemichi, was convicted as a Christian, but managed to flee and disappear.[27]

The privileges of the Hasekura family were rescinded by the Sendai fief, and their property and belongings seized. At this time, in 1640, Hasekura's Christian artifacts were confiscated, and were kept in custody in Sendai until they were rediscovered at the end of the nineteenth century. Around 50 Christian artifacts, such as crosses, rosaries, religious gowns and religious paintings, were seized from Hasekura's estate. An inventory made in 1840 describes the items as belonging to Hasekura Tsunenaga. Nineteen books mentioned in the inventory have since been lost. The artifacts are now preserved in the Sendai City Museum and other museum in Sendai.

Re-discovery

Hasekura’s journey was forgotten in Japan until the reopening of the country after the end of the sakoku policy of isolation. In 1873, a Japanese embassy to Europe (the Iwakura mission), headed by Iwakura Tomomi, learned of Hasekura’s visit to Mexico and Europe when they were shown documents in Venice, Italy.[28]

Hasekura today

Today, there are statues of Hasekura Tsunenaga in the outskirts of Acapulco in Mexico, at the entrance of Havana Bay in Cuba,[29] in Coria del Río in Spain,[30] in the Church of Civitavecchia in Italy, in Tsukinoura, near Ishinomaki,[31]and in a park in Manila, the Philippines.

Approximately 700 inhabitants of Coria del Río near Seville bear the surname Japón (originally Hasekura de Japón), identifying them as descendants of the members of Hasekura Tsunenaga's delegation.

A theme park describing the embassy and displaying a replica of the San Juan Bautista was established in the harbor of Ishinomaki, from which Hasekura initially departed on his voyage.

Shusaku Endo wrote a 1980 novel, titled The Samurai, based on the travels of Hasekura.

Timeline and itinerary

|

|

See also

- Edo period

- Shusaku Endo, the author of the novel The Samurai, a fictitious account of the Hasekura mission

Notes

- ↑ In the Japanese of the era, the sound now transcribed as h was pronounced as an f before all vowels, not just u. Likewise s was sometimes pronounced sh before /e/, not only before /i/, and the syllable ゑ (now read as e), was pronounced ye. On the other hand, the use of x to represent the sh sound is specific to the older pronunciations of Spanish and Portuguese.

- ↑ In the name "Keichō Embassy," the noun "Keichō" refers to the nengō (Japanese era name) after "Bunroku" and before "Genna." In other words, the Keichō Embassy commenced during Keichō, which was a time period spanning the years from 1596 through 1615.

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Japan-Mexico Relations. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ The Keichō Embassy was, in fact, preceded by a Sengoku period mission headed by Mancio Ito with Alessandro Valignano in 1582–1590. Although less well-known and less well-documented, this historic mission is sometimes referred to as the "Tenshō Embassy" because it was initiated in the Tenshō era. This venture was organized by three daimyo of Western Japan—Omura Sumitada, Otomo Sorin and Arima Harunobu.

- ↑ Derek Hayes. Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean: maps of discovery and scientific exploration, 1500–2000. (Seattle, WA: Sasquatch Books, 2001), 17–19

- ↑ 『象志 (Zo-shi)』享保14年 (1729) (Japanese; some passages in English). Letter in University Library. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ Nempe fuisse me quondam Idate Masamune, qui regni Oxu (quod est in Orientali Iaponiæ parte) gubernacula tenet, nec dum quidem per baptismum regenerato, sed tamen Catechumeno, & qui Christianam fidem in suo regno prædicari cupiebat, simul cum alio suæ Curiæ optimate Philippo Francisco Faxecura Retuyemon [sic]{{ ad Romanam Curiam & qui tunc Apostolicæ sedis culmen tenebat SS. Papam Paulum V. qui ad cœlos evolavit, Legatum expeditum.

- ↑ Sebastian Vizcaino, "Account of the search for the gold and silver islands," quoted by Takashi Gonoi. Hasekura Tsunenaga. Jinbutsu sōsho (Shinsōban). (Tōkyō: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2003. ISBN 9784642052276) (Japanese)

- ↑ "Annals of his time," 275

- ↑ "5th document," quoted from "Hasekura Tsunanaga," Gonoi, 77

- ↑ Chimalpahin. "Annals of his time," 4th March 1614, 275

- ↑ Chimalpahin. "Annals of his time," 4th March 1614, 275

- ↑ Chimalpahin. "Annals of his time," 24th March 1614, 275

- ↑ Chimalpahin, "Annals of his time," 9th April 1614, 277

- ↑ Chimalpahin "Annals of his time," 29th May 1614, 283

- ↑ Chimalpahin "Annals of his time," 14th October 1614, 291

- ↑ "Se llegó por fin a salvo, después de algunos peligros y tempestades al puerto de Sanlúcar de Barrameda el 5 de Octubre, donde residiendo el Duque de Medina Sidonia y avisado del arribo, envió carrozas para honrarlos, recibirlos y acomodar en ellas al Embajador y a sus gentiles hombres, habiéndoles preparado un suntuoso alojamiento; y después de haber cumplido con esta obligación como correspondía, y de regalarlos con toda liberalidad, a instancias de la ciudad de Sevilla hizo armar dos galeras, las cuales llevaron a los embajadores a CORIA, donde fueron hospedados por orden de la dicha Ciudad por Don Pedro Galindo, veinticuatro, el cual se ocupó con gran diligencia en tener satisfecho el ánimo del Embajador con todos los placeres y regalos posibles, procurando este entretanto que preparasen ropas nuevas a su séquito y ayudantes para resplandecer con más decoro y pompa a la entrada en Sevilla. Mientras se resolvía esta cuestión, la Ciudad determinó enviar a Coria a Don Diego de Cabrera, hermano del padre Sotelo, a Don Bartolomé López de Mesa, del hábito de Calatraba, a Don Bernardo de Ribera, a Don Pedro Galindo y a multitud de jurados y otros caballeros para que en su nombre besaran la mano al Embajador y lo felicitaron por su llegada a salvo. Sobre esto, quedó el Embajador contentísimo, agradeció mucho a la Ciudad que por su generosidad se complacía en honrarle, y departió con los dichos caballeros mostrando mucha prudencia en su trato." "A veintiuno de Octubre del dicho año la Ciudad hizo otra demostración de la mayor cortesía para el recibimiento del Embajador y del Padre Sotelo mandando carrozas, cabalgaduras y gran número de caballeros y de nobles que lo escoltaron formando una cabalgata de gran solemnidad. Saliendo el Embajador de Coria, vio con sumo placer el honor que se le había preparado, la pompa de los caballeros y la gran cantidad de gente que lo acompañó durante su camino hacia Sevilla." "Cerca de Triana y antes de cruzar el puente, se multiplicó de tal manera el número de carrozas, caballos y gentes de todo género, que no bastaba la diligencia de dos alguaciles y de otros ministros de la justicia para poder atravesarlo. Finalmente compareció el Conde de Salvatierra. Asistente de la Ciudad, con gran número de titulados y con los restantes veinticuatro y caballeros; y el embajador desmontando de la carroza, montó a caballo con el Capitán de su guardia y Caballerizo, vestido sobriamente, a la usanza del Japón, y mostrando al Asistente lo obligado que quedaba de la mucha cortesía y honores que la Ciudad se servía de usar con él, fue puesto en medio del dicho Asistente y Alguaciles Mayores y prosiguiéndose la cabalgata con increíble aplauso y contento de la gente, por la Puerta de Triana se dirigieron al Alcalzar Real." (Scipione Amati, "Historia del regno di Voxu," 1615)

- ↑ "Miércoles 23 de octubre de 1614 años entró en Sevilla el embaxador Japon Faxera Recuremon, embiado de Joate Masamune, rey de Boju. Traía treinta hombres japones con cuchillas, con su capitán de la guardia, y doce flecheros y alabarderos con lanças pintadas y sus cuchillas de abara. El capitán era christiano y se llamaba don Thomas, y era hijo de un mártyr Japón. Venía a dar la obediencia a Su Santidad por su rey y reyno, que se avía baptizado. Todos traían rosarios al cuello; y él venía a recibir el baptismo de mano de Su Santidad. Venía en su compañía fray Luis Sotelo, natural de Sevilla, religioso de San Francisco recoleto. Salieron a Coria a recebirlo por la Ciudad, el veinticuatro don Bartolomé Lopez de Mesa, y el veinticuatro don Pedro Galindo; y junto a la puente los recibió la Ciudad. Entró por la puerta de Triana, y fué al Alcázar, donde la Ciudad lo hospedó, y hizo la costa mientras estubo en Sevilla. Vido la Ciudad, y subió a la Torre. Lunes 27 de octubre de dicho año por la tarde, el dicho embaxador, con el dicho padre fray Luis Sotelo, entró en la Ciudad con el presente de su rey con toda la guardia, todos a caballo desde la puente. Dió su embaxada sentado al lado del asistente en su lengua, que interpretó el padre fray Luis Sotelo, y una carta de su rey, y una espada a su usanza, que se puso en el archibo de la Ciudad. Esta espada se conservó hasta la revolución del 68 que la chusma la robó. La embaxada para su magestad el rey don Felipe Tercero, nuestro señor, no trataba de religión, sino de amistad.(Biblioteca Capitular Calombina 84-7-19 . Memorias..., fol.195)"

- ↑ Extracts from the Old French original:

- "Il y huit jours qu'il passa a St Troppez un grand seigneur Indien, nomme Don Felipe Fransceco Faxicura, Ambassadeur vers le Pape, de la part de Idate Massamuni Roy de Woxu au Jappon, feudataire du grand Roy du Japon et de Meaco. Il avoit plus de trente personnes a sa suite, et entre autre, sept autres pages tous fort bien vetus et tous camuz, en sorte qu'ilz sembloyent presque tous freres. Ils avaient trois fregates fort lestes, lesuqelles portoient tout son attirail. Ils ont la teste rase, execpte une petite bordure sur le derrier faisant une flotte de cheveux sur la cime de la teste retroussee, et nouee a la Chinoise….."

- "… Ilz se mouchent dans des mouchoirs de papier de soye de Chine, de la grandeur de la main a peu prez, et ne se servent jamais deux fois d'un mouchoir, de sorte que toutes les fois qu'ilz ne mouchoyent, ils jestoyent leurs papiers par terre, et avoyent le plaisir de les voir ramasser a ceux de deca qui les alloyent voir, ou il y avoit grande presse du peuple qui s'entre batoit pour un ramasser principallement de ceux de l'Ambassadeur qui estoyent hystoriez par les bordz, comme les plus riches poulletz des dames de la Cour. Ils en portient quantite dans leur seign, et ils ont apporte provision suffisante pour ce long voyage, qu'ilz sont venus faire du deca…."

- "…. Le ses epees et dagues sont faictes en fasson de simmetterre tres peu courbe, et de moyenne longueur et sont sy fort tranchantz que y mettant un feuillet de papier et soufflant ilz couppent le papier, et encore de leur papier quy est beaucoup plus deslie que le notre et est faict de soye sur lesquels ils escrivent avec un pinceau.."

- "…. Quand ilz mangeoient ils ne touchent jamais leur chair sinon avec deux petits batons qu'ils tiennent avec trois doigts." (Francis Marcouin and Keiko Omoto. Quand le Japon s'ouvrit au monde. (Paris: Découvertes Gallimard, 1990. ISBN 207053118X), 114–116)

- ↑ . Body of the text translated from Gonoi quote, p152. Translation of the salutation was done separately. The original Latin of the introduction is as follows:

MAGNI ET UNIVERSALIS SISQ3 [SISQ3 = Sanctissimique]

totius Orbis Patris Domini Pape Pauli s. pedes cum profunda summisse et reuerentia [s. prob. = sanctos, summisse prob. = summissione]

osculando ydate masamune * Imperio Japonico Rex voxu suppliciter dicimus. - ↑ Quo tandem cum anno Salutis 1615. iuvante deo pervenissemus, à SS. Papa magno cum Cardinalium Sacri Collegij Antistitum ac Nobilium concursu, nec non & Rom. populi ingenti lætitia & communi alacritate non modo benignè excepti, verùm & humanissimè tam nos quam etiã tres alij, quos Iaponii Christiani, quatenus eorum circa Christianam Religionem statum Apostolicis auribus intimarent, specialiter destinaverant, auditi, recreati, & prout optabamus, quantocyus expediti.

- ↑ "南蛮国ノ物事、六右衛門物語ノ趣、奇怪最多シ" 伊達治家記録 ("Records of the House of Masamune")

- ↑ Quoted in Gonoi, 229

- ↑ In 1621, Yokozawa Shogen is known to have signed a letter to the Pope together with 17 other Christians from Northern Japan. His name comes in second place after Goto Juan (後藤寿庵). 後藤寿庵

- ↑ Collega alter legatus Philippus Fiaxecura [sic] postquam ad prædictum Regem suum pervenit, ab ipso valdè est honoratus, & in proprium statum missus, ut tam longâ viâ fessus reficeretur, ubi uxorem, filios, domesticos cum multis aliis vasallis Christianos effecit, aliisque nobilibus hominibus consanguineis & propinquis suasit ut fidem reciperent; quam utique receperunt. Dum in his & aliis piis operibus exerceretur ante annum completum post eius regressum magna cum omnium ædificatione & exemplo, multa cum præparatione suis filiis hæreditate præcipua fidei propagationem in suo statu, & Religiosorum in eo regno pretectionem commendatam relinquens, pie defunctus est. De cuius discessu Rex & omnes Nobiles valdè doluerunt, præcipuè tamen Christiani & Religiosi, qui huius viri virtutem & fidei Zelum optimè noverant. Ab ipsis Religiosis, qui eidem sacramenta ministrarunt, eiusque obitui interfuerant; & ab aliis sic per literas accepi. (Luis Sotelo. Ad Urbanum VIII. Pont. Max. de ecclesiae Iaponicae statu relatio. (1634), 16])

- ↑ "National Treasure: Documents of the Keicho Embassy to Europe," 80

- ↑ "National Treasure: Documents of the Keicho Embassy to Europe," 80

- ↑ Sendai museum monograph. Description of the visit of the Hasekura mission to the Venice archives 支倉常長 (Japanese), Sendai City Museum. Retrieved July 8, 2008

- ↑ Statue of Hasekura in Havana, vol. 80 友好の礎 (Japanese). Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ↑ Statue of Hasekura in Coria del Rio.

- ↑ Statue of Hasekura in Tsukinoura. Retrieved July 8, 2008

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boxer, C.R. The Christian Century in Japan, 1549–1650. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, (1951). reprint 1993. ISBN 1857540352.

- de Cardona, Nicolas. (1632) Geographic and Hydrographic Descriptions of Many Northern and Southern Lands and Seas in the Indies, Specifically of the Discovery of the Kingdom of. (Baja California travels series) translated and edited by W. Michael Mathes, 1974. reprint ed. Los Angeles: Dawsons Book Shop, 2003. ISBN 978-0870932359. (translated from the Spanish)

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón, James Lockhart, Susan Schroeder, and Doris Namala. Annals of his time: Don Domingo de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin. (Series Chimalpahin.) Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0804754543

- Date Masamune's Mission to Rome in 1615 国宝「慶長遣欧使節関係資料」, Catalogue of Sendai City Museum, 2001 (Japanese)

- Endo, Shusaku The Samurai. New Directions Publishing Corporation, Reprint ed. (1997), ISBN 0811213463. (A slightly fictional account of Hasekura's expedition).

- Gonoi, Takashi. Hasekura Tsunenaga. Jinbutsu sōsho (Shinsōban). Tōkyō: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2003. ISBN 9784642052276 (Japanese)

- Hayes, Derek. Historical atlas of the North Pacific Ocean: maps of discovery and scientific exploration, 1500–2000. Seattle, WA: Sasquatch Books, 2001. ISBN 1570613117.

- Marcouin, Francis, and Keiko Omoto. Quand le Japon s'ouvrit au monde. Paris: Découvertes Gallimard, 1990. ISBN 207053118X.

- Sotelo, Luis. Ad Urbanum VIII. Pont. Max. de ecclesiae Iaponicae statu relatio. (1634).

- The World and Japan - Tensho and Keicho missions to Europe 16th - 17th century. 世界と日本ー天正・慶長の使節, Sendai City Museum, 1995. (Japanese)

External links

All links retrieved August 25, 2016.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.