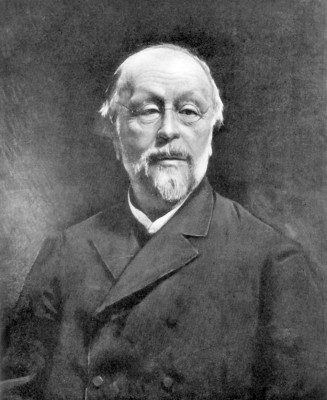

Hippolyte Taine

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine (April 21, 1828 - March 5, 1893) was a French critic and historian. He was the chief theoretical influence of French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism, and one of the first practitioners of historicist criticism. Taine is particularly remembered for his three-pronged approach to the contextual study of a work of art, based on the aspects of what he called race, milieu, and moment. In literature this approach expresses itself in the literary movement of historicism, of which Taine was a leading proponent. Historicism treats literature not as a disembodied work of art, but as the product of a specific historical and cultural context. This historicism was born of Taine's philosophical commitments. Taine was a thorough-going determinist, who embraced positivism.

Race, milieu, and moment

Taine argued that literature was largely the product of the author's environment, and that an analysis of that environment could yield a perfect understanding of the work of literature. In this sense he was a positivist (see Auguste Comte), though with important differences. Taine did not mean race in the specific sense now common, but rather the collective cultural dispositions that govern everyone without their knowledge or consent. What differentiates individuals within this collective race, for Taine, was milieu: the particular circumstances that distorted or developed the dispositions of a particular person. The moment is the accumulated experiences of that person, which Taine often expressed as "momentum"; to later critics, however, Taine's conception of moment seems to have more in common with Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age.

Early years

Taine was born at Vouziers, Ardennes (département), France, the son of Jean Baptiste Taine, an attorney at law. He was taught at home by his father until his eleventh year, also attending a small school. In 1839, owing to his father's serious illness, he was sent to an ecclesiastical pension at Rethel. J. B. Taine died on September 8, 1840, leaving a small income to his widow, his two daughters, and his son. In the spring of 1841, Hippolyte was sent to Paris, and entered as a boarder at the Institution Mathé, where the pupils attended the classes of the College Bourbon. His mother accompanied him.

Taine distinguished himself at school. At age 14 he had already drawn up a systematic scheme of study, from which he never deviated. He allowed himself twenty minutes' playtime in the afternoon and an hour's music after dinner; the rest of the day was spent working. In 1847, as vétéran de rhétorique, he carried off six first prizes in the general competition, the prize of honor, and three accessits; he won all the first school prizes, the three science prizes, and two prizes for dissertation. It was at the College Bourbon that he formed lifelong friendships with several of his schoolfellows who afterwards were to exercise a lasting influence upon him. Among these were Lucien Anatole Prevost-Paradol, for many years his closest friend; Planat, the future "Marcelin" of the Vie Parisienne; and Cornélis de Witt, who introduced him to François Pierre Guillaume Guizot in 1846.

Middle years

Initially Taine planned to pursue a career in public education. In 1848 he took both his baccalauréat degrees, in science and letters, and passed first into the École Normale; among his rivals, who passed in at the same time, were Edmond François Valentin About, Francisque Sarcey, and Frédéric du Suckau. Among those of Taine's fellow-students who afterwards made a name in teaching, letters, journalism, the theater and politics, etc., were Paul-Armand Challemel-Lacour, Alexis Chassang, Louis Aubé, Philippe Perraud, Jules Ferry, Octave Gréard, Prévost-Paradol and Pierre Émile Levasseur.

Taine made his influence felt among them at once; he amazed everybody by his learning, his energy, his hard work, and his facility both in French and Latin, in verse as well as in prose. He devoured Plato, Aristotle, the early Church Fathers, analyzing and classifying all that he read. He already knew English, and set himself to master German in order to read Hegel in the original. His brief leisure was devoted to music.

The teachers of his second and third years, Emile Deschanel, Nicolas Eugène Géruzez, Eugène Auguste Ernest Havet, Charles Auguste Désiré Filon, Émile Saisset and Jules Simon, were unanimous in praising his character and intellect, though they found fault with his unmeasured taste for classification, abstraction, and formula. The Minister of Public Instruction, however, judged Taine less severely, and appointed him provisionally to the chair of philosophy at the college of Toulon on October 6, 1851; he never entered upon his duties, as he did not wish to be so far from his mother, so on October 13 he was transferred to Nevers as a substitute. Two months later, on December 27, the coup d'état that ended the Second Republic took place, after which every university professor was regarded with suspicion; many were suspended, others resigned. In Taine's opinion it was the duty of every man, after the plebiscite of the December 10, to accept the new state of affairs in silence; but the universities were not only asked for their submission, but also for their approbation.

At Nevers they were requested to sign a declaration expressing their gratitude towards the President of the Republic (Louis Napoleon) for the measures he had taken. Taine was the only one to refuse his endorsement. He was at once marked down as a revolutionary, and in spite of his success as a teacher and of his popularity among his pupils, he was transferred on March 29, 1852 to the lycée of Poitiers as professor of rhetoric, with a sharp warning to be careful for the future. Here, in spite of an abject compliance with the stringent rules imposed upon him, he remained in disfavor, and on September 25, 1852 he was appointed assistant professor of the sixth class at the lycée of Besançon. This time he could bear it no longer, and he applied for leave, which was readily granted him on October 9, 1852, and renewed every year till his decennial appointment came to an end. It was in this painful year, during which Taine worked harder than ever, that the fellowship of philosophy was abolished.

As soon as Taine heard of this he at once began to prepare himself for the fellowship in letters, and to work hard at Latin and Greek themes. On April 10, 1852 a decree was published by which three years of preliminary study were necessary before a candidate could compete for the fellowship, but by which a doctor's degree in letters counted as two years. Taine immediately set to work at his dissertations for the doctor's degree; on June 8, (1852) they were finished, and 150 pages of French prose on the Sensations and a Latin essay were sent to Paris. On July 15 he was informed that the moral tendency of his Essay on the Sensations made it impossible for the Sorbonne to accept it, so for the moment he laid this work aside, and on August 1 he began an essay on La Fontaine. He then started for Paris, where an appointment which was equivalent to a suspension awaited him. His university career was over, and he was obliged to devote himself to letters as a profession. In a few months his two dissertations, De personis Platonicis and the essay on La Fontaine's fables were finished, and on May 30, 1853 he took his doctor's degree. This was the last act of his university career; his life as a man of letters was now to begin.

No sooner had he deposited his dissertations at the Sorbonne than he began to write an essay on Livy for one of the competitions set by the Académie française. The moral tendency of his work excited lively opposition, and after much discussion the competition was postponed till 1855; Taine toned down some of the censured passages, and the work was crowned by the Academy in 1855. The essay on Livy was published in 1856 with the addition of a preface setting forth determinist doctrines, much to the disgust of the Academy. In the beginning of 1854, after six years of uninterrupted efforts, Taine broke down and was obliged to rest: but he found a way of utilizing his enforced leisure; he let himself be read to, and for the first time his attention was attracted to the French Revolution; he acquired also a knowledge of physiology in following a course of medicine. In 1854 he was ordered for his health to the Pyrenees, and Louis Christoph François Hachette, a publisher, asked him to write a guide-book of that region. Taine's book was a collection of vivid descriptions of nature, historical anecdotes, graphic sketches, satirical notes on the society which frequents watering places, and underlying the whole book was a vein of stern philosophy; it was published in 1855.

The year 1854 was an important one in the life of Taine. His enforced leisure, the necessity of mixing with his fellowmen, and of travelling, tore him from his cloistered existence and brought him into more direct contact with reality. His method of expounding philosophy underwent a change. Instead of employing the method of deduction, of starting with the most abstract idea and following it step by step to its concrete realization, henceforward he starts from the concrete reality and proceeds through a succession of facts until he arrives at the central idea. His style also became vivid and full of color. Simultaneously with this change in his works his life became less self-centered and solitary. He lived with his mother in the Île Saint-Louis, and now he once more associated with his old friends, Planat, Prévost-Paradol and About. He made the acquaintance of Renan, and through Renan that of Sainte-Beuve, renewing friendly relations with M. Havet, who for three months had been his teacher at the École Normale. These years (1855-1856) were Taine's periods of greatest activity and happiness in production. On February 1, 1855 he published an article on Jean de La Bruyère in the Revue de l'Instruction Publique.

In the same year he published 17 articles in this review and 20 in 1856 on the most diverse subjects, ranging from Menander to Macaulay. On August 1, 1855 he published a short article in the Revue des Deux Mondes on Jean Reynaud. On July 3, 1856 appeared his first article in the Débats on Saint-Simon, and from 1857 onwards he was a constant contributor to that journal. But he was seeking a larger field. On January 17, 1856 his history of English literature was announced, and from January 14, 1855 to October 9, 1856 he published in the Revue de l'Instruction Publique a series of articles on the French philosophers of the nineteenth century, which appeared in a volume at the beginning of 1857. In this volume he energetically attacked the principles which underlie the philosophy of Victor Cousin and his school, with an irony which amounts at times to irreverence. The book closes with the sketch of a system in which the methods of the exact sciences are applied to psychological and metaphysical research. The work itself met with instantaneous success, and Taine became famous.

Up till that moment the only important articles on his work were an article by About on the Voyage aux Pyrenees, and two articles by Guizot on his Livy. After the publication of Les Philosophes Français, the articles of Sainte-Beuve in the Moniteur (9th and 16th March 1856), of Shereri in the Bibliothèque Universelle (1858), and of Planche in the Revue des Deux Mondes (April 1, 1857) show that from this moment he had taken a place in the front rank of the new generation of men of letters. Elme Marie Caro published an attack on Taine and Ernest Renan, called "L'Idée de Dieu dans une Jeune École," in the Revue Contemporaine of June 15, 1857. Taine answered all attacks by publishing new books. In 1858 appeared a volume of Essais de Critique et d'Histoire; in 1860 La Fontaine et ses Fables, and a second edition of his Philosophes Français. During all this time he was persevering at his history of English literature up to the time of Byron. It was from that moment that Taine's influence began to be felt; he was in constant intercourse with Renan, Sainte-Beuve, Sherer, Gautier, Flaubert, Saint-Victor and the Goncourts, giving up a little of his time to his friends and to the calls of society. In 1862 Taine came forward as a candidate for the chair of literature at the Polytechnic School, but M. de Loménie was elected in his place.

The following year, however, in March, Marshal Randon, Minister of War, appointed him examiner in history and German to the military academy of Saint Cyr, and on October 26, 1864 he succeeded Eugene Viollet-le-Duc as professor of the history of art and aesthetics at the École des Beaux Arts. Renan's appointment at the College de France and Taine's candidature for the Polytechnic School had alarmed the eloquent ecclesiastic Félix Dupanloup, who in 1863 issued an Avertissement à la Jeunesse et aux Pères de Famille, which consisted of a violent attack upon Taine, Renan and Maximilien-Paul-Émile Littré. Renan was suspended, and Taine's appointment to Saint Cyr would have been cancelled but for the intervention of the Princess Mathilde.

In December 1863 his Histoire de la Littérature Anglaise was published, prefaced by an introduction in which Taine's determinist views were developed in the most uncompromising fashion. In 1864 Taine sent this work to the Academy to compete for the Prix Bordin. Frédéric Alfred Pierre, comte de Falloux and Mgr. Dupanloup attacked Taine with violence; he was warmly defended by Guizot: finally, after three days of discussion, it was decided that as the prize could not be awarded to Taine, it should not be awarded at all. This was the last time Taine sought the suffrages of the Academy save as a candidate, in which quality he appeared once in 1874 and failed to be elected; Mézières, Caro and Dumas were rival candidates. He stood twice for election in 1878. After losing out to H. Martin in May, he was at last elected in November in place of M. Loménie. In 1866 he received the "Legion d'Honneur" (Legion of Honor), and on the conclusion of his lectures in Oxford on Corneille and Racine, the University conferred upon him (1871) its honorary degree of Doctorate of Civil Law (D.C.L.).

In 1864 he spent February to May in Italy, which furnished him with several articles for the Revue des Deux Mondes from December 1864 to May 1866. In 1865 appeared La Philosophie de l'Art, in 1867 L'Idéal dans l'Art, followed by essays on the philosophy of art in the Netherlands (1868), in Greece (1869), all of which short works were republished later (in 1880) as a work on the philosophy of art. In 1865 he published his Nouveaux Essais de Critique et d'Histoire; from 1863 to 1865 appeared in La Vie Parisienne the notes he had taken for the past two years on Paris and on French society under the sub-title of "Vie et Opinions de Thomas Frédéric Graindorge," published in a volume in 1867, the most personal of his books, and an epitome of his ideas. In 1867 appeared a supplementary volume to his history of English literature, and in January 1870 his Théorie de l'Intelligence. In 1868 he married Mademoiselle Denuelle, the daughter of a distinguished architect.

Later years

He had made a long stay in England in 1858, and had brought back copious notes, which, after a second journey in 1871, he published in 1872 under the title of Notes sur l'Angleterre. On June 28, 1870 he started to visit Germany, but his journey was abruptly interrupted by the outbreak of the Franco Prussian War; his project had to be abandoned, and Taine, deeply shaken by the events of 1870, felt that it was the duty of every Frenchman to work solely in the interests of France. On October 9, 1870 he published an article on "L'Opinion en Allemagne et les Conditions de la Paix," and in 1871 a pamphlet on Le Suffrage Univend; and it was about this time also that the more or less vague ideas which he had entertained of writing on the French Revolution returned in a new and definite shape. He determined to trace in the Revolution of 1789 the reason of the political instability from which modern France was suffering. From the autumn of 1871 to the end of his life his great work, Les Origines de la France Contemporaine, occupied all his time, and in 1884 he gave up his professorship in order to devote himself wholly to his task; but he succumbed before it was finished, dying in Paris. In the portion of the work which remained to be finished Taine had intended to draw a picture of French society and of the French family, and to trace the development of science in the nineteenth century. He had also planned a complementary volume to his Théorie de l'Intelligence, to be entitled Un Traité de la Volatile.

Achievements

The Origines de la France Contemporaine, Taine's monumental achievement, stands apart from the rest of his work. His object was to explain the existing constitution of France by studying the more immediate causes of the present state of affairs—the last years of the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution and the beginning of the nineteenth century, to each of which several volumes were assigned. His work also had another object, although he was perhaps hardly conscious of it, namely, the study man in one of his pathological crises. Taine is interested in studying human nature, checking and endorsing the pessimism and misanthropy of Graindorge. The problem which Taine set himself was an inquiry into the centralization of modern France so that all individual initiative was practically non-existent, and why the central power, whether in the hands of a single ruler or an assembly, is the sole and only power. He also wished to expose the error underlying two prevalent conceptions of the Revolution – (1) The proponents view that the Revolution destroyed absolutism and set up liberty; (2) The opponents view that the Revolution destroyed liberty instead of establishing it, based on the notion that France was less centralized before the Revolution. On the contrary, Taine argues, the Revolution did not establish liberty, it merely caused absolutism to change hands, and France was not less centralized before 1789 than after 1800. France was already a centralized country before 1789, and grew rapidly more and more so from the time of Louis XIV onwards. The Revolution merely gave it a new form.

The Origines differ from the rest of Taine's work in that, although he applies to a period of history the method which he had already applied to literature and the arts, he is unable to approach his subject in the same spirit; he loses his philosophic calm; he cannot help writing as a Frenchman, and he lets his feelings have play; but what the work loses thus in impartiality it gains in spirit.

Philosopher

Taine was the philosopher of the epoch which succeeded the era of romanticism in France. The romantic era had lasted from 1820 to 1850. It had been the result of a reaction against the rigidity of the classical school. The romantic school introduced the principle of individual liberty, applying the spirit of the Revolution in both matter and style; it was a brilliant epoch, rich in men of genius, but towards 1850 it had reached its decline, and a young generation rose, tired in turn of its conventions, its hollow rhetoric, its pose of melancholy, armed with new principles and fresh ideals. Their ideal was truth; their watchword liberty; to get as near as possible to scientific truth became their object. Taine was the mouthpiece of this period, or rather one of its most authoritative spokesmen.

Many attempts have been made to apply one of Taine's favorite theories to himself, and to define his predominant and preponderant faculty. Some critics have held that it was the power of logic, a power which was at the same time the source of his weakness and of his strength. He had a passion for abstraction. "Every man and every book," he said, "can be summed up in three pages, and those three pages can be summed up in three lines." He considered everything a mathematical problem, whether the universe or a work of art: "C'est beau comme un syllogisme, (It's beautiful, like a syllogism)" he said of a sonata of Beethoven. Taine's theory of the universe, his doctrine, his method of writing criticism and history, his philosophical system, are all the result of this logical gift, this passion for reasoning, classification and abstraction. But Taine's imaginative quality was as remarkable as his power of logic; hence the most satisfactory definition of Taine's predominating faculty would be one which comprehended the two gifts. M. Lemaître gave us this definition when he called Taine a poète-logicien (poet-logician); M. Bourget likewise when he spoke of Taine's imagination philosophique, and M. Barrès when he said that Taine had the power of dramatizing abstractions. For Taine was a poet as well as a logician; and it is possible that the portion of his work which is due to his poetic and imaginative gift may prove the most lasting.

Doctrine

Taine's doctrine consisted in an inexorable determinism, a negation of metaphysics; as a philosopher he was a positivist. Enamored of the precise and the definite, the spiritualist philosophy in vogue in 1845 positively maddened him. He returned to the philosophy of the eighteenth century, especially to Condillac and to the theory of transformed sensation. Taine presented this philosophy in a vivid, vigorous and polemical form, and in concrete and colored language which made his works more accessible, and consequently more influential, than those of Auguste Comte. Hence to the men of 1860 Taine was the true representative of positivism.

Critical work

Taine's critical work is considerable; but all his works of criticism are works of history. Hitherto history had been to criticism as the frame is to the picture; Taine reversed the process, and studied literary personages merely as specimens and productions of a certain epoch. He started with the axiom that the complete expression of a society is to be found in its literature, and that the way to obtain an idea of a society is to study its literature. The great writer is not an isolated genius; he is the result of a thousand causes; firstly, of his race; secondly, of his environment; thirdly, of the circumstances in which he was placed while his talents were developing. Hence Race, Environment, Time (usually written, as closer to Taine's French terms, "race, milieu, and moment")—these are the three things to be studied before the man is taken into consideration. Taine completed this theory by another, that of the predominating faculty, the faculté maîtresse. This consists in believing that every man, and especially every great man, is dominated by one faculty so strong as to subordinate all others to it, which is the center of the man's activity and leads him into one particular channel. It is this theory, obviously the result of his love of abstraction, which is the secret of Taine's power and of his deficiencies. He always looked for this salient quality, this particular channel, and when he had once made up his mind what it was, he massed up all the evidence which went to corroborate and to illustrate this one quality, and necessarily omitted all conflicting evidences. The result was an inclination to lay stress on one side of a character or a question to the exclusion of all others.

Science

Taine served science unfalteringly, without looking forward to any possible fruits or result. In his work we find neither enthusiasm nor bitterness, neither hope nor despair; merely a hopeless resignation. The study of mankind was Taine's incessant preoccupation, and he followed the method already described. He made a searching investigation into humanity, and his verdict was one of unqualified condemnation. In Thomas Graindorge we see him aghast at the spectacle of man's brutality and woman's folly. In man he sees the primeval savage, the gorilla, the carnivorous and lascivious animal, or else the maniac with diseased body and disordered mind, to whom health, either of mind or body, is but an accident. Taine is appalled by the bête humaine; and in all his works we are conscious, as in the case of Voltaire, of the terror with which the possibilities of human folly inspire him. It may be doubted whether Taine's system, to which he attached so much importance, is really the most lasting part of his work, just as it may be doubted whether a sonata of Beethoven bears any resemblance to a syllogism. For Taine was an artist as well as a logician, an artist who saw and depicted what he saw in vital and glowing language. From the artist we get his essay on Jean de La Fontaine, his articles on Honoré de Balzac and Jean Racine, and the passages on Voltaire and Rousseau in the Ancien Régime. Moreover, not only was Taine an artist who had not escaped from the influence of the romantic tradition, but he was by his very method and style a romanticist. His emotions were deep if not violent, his vision at times almost lurid. He sees everything in startling relief and sometimes in exaggerated outline, as did Balzac and Victor Hugo. Hence his predilection for exuberance, strength and splendor; his love of Shakespeare, Titian and Rubens; his delight in bold, highly-colored themes.

Influence

Taine had an enormous influence within French literature specifically, and literary criticism in general. The work of Emile Zola, Paul Charles Joseph Bourget and Guy de Maupassant all owe a great debt to Taine's influence. He was also one of the founders of the critical notion of historicism, which insists on placing the literary work in its historical and social context. This view became increasingly important over time, and finds its current expression in the literical critical movement of New historicism.

Writings

- 1853 De personis Platonicis. Essai sur les fables de La Fontaine

- 1854 Essai sur Tite-Live

- 1855 Voyage aux eaux des Pyrénées

- 1856 Les philosophes français du XIXe siècle

- 1857 Essais de critique et d'histoire

- 1860 La Fontaine et ses fables

- 1864 Histoire de la littérature anglaise, 4 vol. L'idéalisme anglais, étude sur Carlyle. Le positivisme anglais, étude sur Stuart Mill

- 1865 Les écrivains anglais contemporains. Nouveaux essais de critique et d'histoire. *Philosophie de l'art

- 1866 Philosophie de l'art en Italie. Voyage en Italie, 2 vol.

- 1867 Notes sur Paris. L'idéal dans l'art

- 1868 Philosophie de l'art dans les Pays-Bas

- 1869 Philosophie de l'art en Grèce

- 1870 De l'intelligence, 2 vol.

- 1871 Du suffrage universel et de la manière de voter. Un séjour en France de 1792 à 1795. Notes sur l'Angleterre

- 1876-1894 Origines de la France contemporaine (t. I : L'ancien régime ; II à IV : La Révolution ; V et VI : Le Régime moderne)

- 1894 Derniers essais de critique et d'histoire

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Kafker, Frank A., James M. Laux, Darline Gay Levy. (eds.) The French Revolution : conflicting interpretations. Malabar, FL: Krieger Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 1575240920

- Nias, Hilary. The artificial self: the psychology of Hippolyte Taine. Oxford, UK: Legenda, 1999. ISBN 1900755181

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, in turn, gives the following references:

- The official life, H. Taine, sa vie et sa correspondence, was published in 3 vols. in 1902-1905 (Eng. trans. by Mrs. RL Devonshire, 1902-1908).

- His friend, ME Boutmy, published an appreciative study of Taine's philosophy in his Taine, Scherer, Laboulaye. (Paris, 1901).

- Albert Sorel, Nouveaux essais d'histoire et de critique. (1898)

- Gabriel Monod, Les Maîtres de l'histoire. (Paris, 1894)

- Émile Faguet, Politiques moralities au XIX' siècle. (Paris, 1900)

- P Lacombe, La psychologie des individus et des sociétés chez Taine (1906)

- P Neve, La philosophie de Taine (1908)

- Victor Giraud, Essai sur Taine, son œuvre et son influence, d'après des documents inédits. (and ed., 1902)

- V Giraud, Bibliographie de Taine. (Paris, 1902).

- A comprehensive list of books and articles on Taine is given in Hugo Paul Thiem's Guide bibliographique de la littérature française de 1800 a 1906. (Paris, 1907).

- Taine's historical work was adversely criticized, especially by François Victor Alphonse Aulard in lectures delivered at the Sorbonne in 1905-1906 and 1906-1907 (Taine, historien de la révolution française, 1907), devoted to destructive criticism of Taine's work on the French Revolution.

External links

All links retrieved January 9, 2018.

- Works by Hippolyte Taine. Project Gutenberg

| Preceded by: Louis de Loménie |

Seat 25 Académie française 1878–1893 |

Succeeded by: Albert Sorel |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.