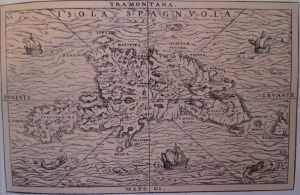

Hispaniola

View of Haitian Landscape Hispaniola | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Caribbean |

| Archipelago | Greater Antilles |

| Area | 76,480 km² (29,530 sq mi) (22nd) |

| Coastline | 3,059 km (1,901 mi) |

| Highest point | Pico Duarte (3,175 m (10,420 ft)) |

| Political division | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 18,943,000 (as of 2005) |

Christopher Columbus landed on Hispaniola on December 5, 1492 and named it La Isla Española, "The Spanish Island," which was eventually Anglicized to Hispaniola. It is said that when he first laid eyes on its shores, he termed it "La Perle des Antilles" or "the Pearl of the Caribbean."

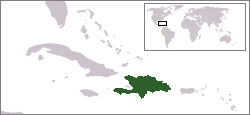

The island is the second largest island of the West Indies, with an area of 29,418 square miles (76,192 square km). To its west is Cuba, southwest is Jamaica, and Puerto Rico is to the east. The Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands lie to the northwest. Haiti occupies the western third of the island, the remaining eastern two-thirds of the island make up the Dominican Republic.

The Taino called the island Quisqueya (or Kiskeya), which means "mother of the earth," and is still used throughout the island.

Geography

Hispaniola, originally known as Española, is the second largest island in the West Indies, lying within the Greater Antilles. It is politically divided into the Republic of Haiti in the west and the Dominican Republic in the east. The island's area is 29,418 square miles (76,192 square km); with its greatest length at nearly 400 miles (650 km) long, and a width of 150 miles (241 km). It is the second-largest island in the Caribbean (after Cuba), with an area of 76,480 km².

The island of Cuba lies to the northwest across the Windward Passage, the strait connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Caribbean Sea. To Hispaniola's southwest lies Jamaica, separated by the Jamaica Channel. Puerto Rico lies east of Hispaniola across the Mona Passage. The Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands lie to the northwest.

Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico are collectively known as the Greater Antilles. These islands are made up of continental rock, as distinct from the Lesser Antilles, which are mostly young volcanic or coral islands.

The Island of Hispaniola has five major mountain ranges:

- The Central Range, known in the Dominican Republic as the Cordillera Central, span the central part of the island, extending from the south coast of the Dominican Republic into northwestern Haiti, where they are known as the Massif du Nord. This mountain range boasts the highest peak in the Antilles, Pico Duarte at 10,128 feet (3,087 meters) above sea level.

- The Cordillera Septentrional runs parallel to the Central Range across the northern end of the Dominican Republic, extending into the Atlantic Ocean as the Samaná Peninsula. The highest point in the Cordillera Septentrional is Pico Diego de Ocampo. The Cordillera Central and Cordillera Septentrional are separated by the lowlands of the Cibao Valley and the Atlantic coastal plains, which extend westward into Haiti, becoming the Plaine du Nord (Northern Plain).

- The lowest of the ranges is the Cordillera Oriental, in the eastern part of the island.

- The Sierra de Neiba rises in the southwest of the Dominican Republic, and continues northwest into Haiti, parallel to the Cordillera Central, as the Montagnes Noires, Chaîne des Matheux and the Montagnes du Trou d'Eau. The Plateau Central lies between the Massif du Nord and the Montagnes Noires, and the Plaine de l'Artibonite lies between the Montagnes Noires and the Chaîne des Matheux, opening westward toward the Gulf of Gonâve.

- The southern range begins in the southwestern–most Dominican Republic as the Sierra de Bahoruco, and extends west into Haiti as the Massif de la Selle and the Massif de la Hotte, which form the mountainous spine of Haiti's southern peninsula. Pic de la Selle is the highest peak in the southern range and is the highest point in Haiti, at 8,793 feet (2,680 meters) above sea level. A depression runs parallel to the southern range, between the southern range and the Chaîne des Matheux-Sierra de Neiba. It is known as the Plaine du Cul-de-Sac in Haiti, and Haiti's capital Port-au-Prince lies at its western end. The depression is home to a chain of salty lakes, including the Saumatre Lagoon in Haiti and Lake Enriquillo in the Dominican Republic.

The climate of Hispaniola is generally humid and tropical. There are four distinct eco-regions on the island.

- The Hispaniolan moist forests eco-region covers approximately 50 percent of the island, especially the northern and eastern portions, predominantly in the lowlands but extending up to 2,100 meters elevation.

- The Hispaniolan dry forests eco-region occupies approximately 20 percent of the island, lying in the rain shadow of the mountains in the southern and western portion of the island and in the Cibao valley in the north-center part of the island.

- The Hispaniolan pine forests occupy the mountainous 15 percent of the island, above 850 meters in elevation.

- The Enriquillo wetlands are a flooded grasslands and savannas eco-region that surround a chain of lakes and lagoons that includes Lake Enriquillo, Rincón Lagoon, and Lake Caballero in the Dominican Republic and Saumatre Lagoon and Trou Cayman in Haiti.

In general, the mountains are forested and sparsely populated, however, in some places, mostly in Haiti, the population pressure has brought about deforestation of land for cultivation.

Mostly occurring throughout the humid mountainous regions, coffee growth is the chief agricultural activity of the highlands. Numerous amounts of crops, mainly cacao, are grown on the heavily populated northern plains, especially in the humid eastern section known as La Vega Real, “The Royal Plain.” In the upper Yaque Plain, tobacco is a dominant crop. In the semi-arid lower plains irrigated rice is the crop of choice. Along the northern coast, the Plaine du Nord, in the west of Haiti, sugarcane and sisal are the main crops. The southern plains of the island are also very productive, boasting sugarcane, livestock pasture, and cotton, although irrigation is a necessity in many of its areas.

History

The island of Hispaniola was occupied by Amer-Indians for at least 5,000 years prior to the European arrival in the Americas. Multiple waves of indigenous immigration to the island had occurred, mainly from Central and South America. Those from the South American continent were descendants of the Arawak, who passed through Venezuela. These tribes blended through marriage, forming the Taino, who greeted Christopher Columbus upon his arrival. It is believed that there were probably several million of these peaceful natives living on the island at that time.

Columbus had visited Cuba and the Bahamas before landing on Hispaniola (known alternatively as Quisqueya, Haití, or Bohío to the natives) in December 1492. However, it was Hispaniola that seemed to impress Columbus most strongly. It is said that when he first laid eyes on its shores, he termed it "La Perle des Antilles" or "the Pearl of the Caribbean." His journal described the beauty of the high, forested mountains and large river valleys which were inhabited by a peaceful amiable people. On his return the following year, he quickly founded the first permanent European settlement in America.

European colonization

European colonization of the island began in earnest the following year, when 1,300 men arrived from Spain under the watch of Bartolomeo Columbus (Christopher's cousin).

In 1493 the town of Nueva Isabela was founded on the north coast, near modern day Puerto Plata. From there the Spaniards could easily reach the gold found in the interior of the island. After the 1496 discovery of gold in the south, Bartolomeo founded the city of Santo Domingo, which is the oldest permanent European settlement in the Americas.

The Taino, already weakened by diseases they had no immunity to, were forced into hard labor, panning for gold under repressive and deplorable conditions. Nicolas Ovando, who succeeded Bartolomeo Columbus as governor of the colony, organized a "feast" for the Taino chiefs near present day Port au Prince, Haiti. The Taino were burned to death when the Spaniards set fire to the building they had assembled in for the feast. Those who escaped the fire were tortured to death. A similar campaign was carried out on the eastern part of the island. With their leadership virtually wiped out, resistance by the remaining population was for the most part eliminated.

The remaining Taino population was quickly decimated through the ravages of famine, the cruelties of forced labor, and the introduction of smallpox. In 1501, the colony began to import African slaves.

After 25 years of Spanish occupation, the Taino population had shrunk to less than 50,000 in the Spanish–dominated sections of the island. Within another generation, most of the native population had intermarried with either the Spanish or the African descendants. The people of this blended ancestry are known today as the Dominicans.

By the early sixteenth century, the gold deposits of Hispaniola were becoming exhausted. Most of the Spanish left for Mexico as word of that area's riches spread. Only a few thousand Spanish remained, most of whom were of mixed blood with the Taino. They began to raise livestock (Columbus had introduced pigs and cattle to the island), which they used to supply passing ships on their way to the mainland.

By the early seventeenth century, the island and its smaller neighbors (notably Tortuga) became regular stopping points for Caribbean pirates. In 1606, the king of Spain ordered all inhabitants of Hispaniola to move close to Santo Domingo for their protection. Rather than secure the island, however, this resulted in French, English and Dutch pirates establishing bases on the now-abandoned north and west coasts.

In 1665, French colonization of the island was officially recognized by Louis XIV. The French colony was given the name Saint-Domingue. In the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Spain formally ceded the western third of the island to France. Saint-Domingue quickly came to overshadow the east in both wealth and population. Nicknamed the "Pearl of the Antilles," it became the richest colony in the West Indies and one of the richest in the world. Large sugar cane plantations were established and worked by hundreds of thousands of African slaves who were imported to the island.

Independence

In 1791, a major slave revolt erupted in Saint-Domingue, inspired in part by events taking place in France during the French Revolution. Disputes between whites and mulattos in Saint Domingue led Toussaint Louverture, a French black man, to take charge of the revolt. Since the entire island had been ceded to France in 1795 (Treaty of Basilea) L'Ouverture and his followers claimed the entire island. In 1801, he succeeded in unifying the island.

In 1804, following a failed attempt by Napoleonic troops to reestablish slavery on the island, the Republic of Haiti was proclaimed, with Jean-Jacques Dessalines as its first head of state. Haiti is the second oldest country in the Americas after the United States and the oldest independent nation in Latin America.

By 1808, after various degrees of instability, Santo Domingo reverted to Spanish rule. Two years later in 1810 the French finally left Santo Domingo.

Spanish lieutenant governor José Núñez de Cáceres declared the colony's independence as the state of Spanish Haiti (Haití Español) on November 30, 1821, requesting admission to the Republic of Gran Colombia, but Haitian liberation forces, led by Jean-Pierre Boyer, unified the entire island, ending 300 years of colonial domination and slavery just nine weeks later. For the next two decades Haiti controlled the entire island; a period which the Dominicans refer to as "The Haitian Occupation."

In 1838 Juan Pablo Duarte founded an underground resistance group, La Trinitaria, that sought independence of the eastern section of the island with no foreign intervention. Ramón Matías Mella and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez (the latter one being a mestizo), in spite of not being among the founding members, went on to be decisive in the fight for independence and are now hailed (along with Duarte) as the Founding Fathers of the Dominican Republic. On February 27, 1844, the Trinitarios declared independence from Haiti, backed by Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle-rancher from El Seibo. The Dominican Republic's first Constitution, modeled after that of the U.S., was adopted on November 6, 1844.

Leadership of the Dominican Republic threw the nation into turmoil for the next two decades, until they eventually sought outside help. In 1861 at President Pedro Santana's request, the country reverted back to a colonial state of Spain, the only Latin American nation to do so. Quickly regretting this action, Spain was forced out. Soon after, the United States was requested to take over. President Ulysses S. Grant supported the idea, but it was defeated by that nation's Congress.

Haitian authorities in the meantime, fearful of the reestablishment of Spain as colonial power, gave refuge and logistics to revolutionaries seeking to re-establish the independent nation of the Dominican Republic. The ensuing civil war, known as the War of Restoration, was led by two black men of Haitian descent: Ulises Heureaux, who was also a three-time President of the Dominican Republic, and General Gregorio Luperón. The War of Restoration began on August 16, 1863; after two years of fighting, Spanish troops abandoned the island.

Twentieth century

Both Haiti and the Dominican Republic faced a great deal of political instability in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The United States occupied both countries and temporarily took over their customs duties.

The Dominican Republic and the United States, in 1906, entered into a 50-year treaty under which the former gave control of its administration and customs to the United States. In exchange, the US agreed to help reduce the immense foreign debt that the nation had accrued. Between 1916 and 1924, thousands of US troops occupied and administered the country. During this period, roads, schools, communications and sanitation facilities were built, and other projects undertaken. Several years of fiscal stability followed.

However, political instability and assassinations prompted the administration of President William H. Taft to dispatch a commission to Santo Domingo on September 24, 1912, to mediate among the warring factions. The result was the appointment of Adolfo Alejandro Nouel Bobadilla, a neutral figure, to the position of provisional president on November 30. Nouel Bobadilla stepped down on March 31, 1913, as the task proved too much for him to fulfill.

Continued unrest and instability prompted the US to demand presidential elections. As a result, Ramón Báez Machado was elected provisional president in the Dominican Republic. By 1916, the U.S. took complete control of the Dominican Republic, having grown tired of its role of mediator, due to the stepping down of Ramón Báez Machado and the rise of Desiderio Arias (who refused to take power). The results were immediate with the budget balanced, debt reduced, and economic growth renewed. When the U.S. military prepared to depart the island in 1924, they first created a modern military, which eventually became the instrument by which future Dominican authoritarians would seize power.

Meanwhile, throughout the nineteenth century, Haiti was ruled by a series of presidents, most of whom remained in office only briefly. Meanwhile, the country's economy was gradually dominated by foreigners, particularly from Germany. Concerned about German influence, and disturbed by the lynching of President Guillaume Sam by an enraged crowd, the United States invaded and occupied Haiti in 1915. The U.S. imposed a constitution (written by future president Franklin D. Roosevelt) and applied an old system of compulsory corvée labor to everyone. Previously this system had been applied only to members of the poor, black majority. The occupation had many long-lasting effects on the country. United States forces built schools, roads and hospitals, and launched a campaign that eradicated yellow fever from the island. Unfortunately, the establishment of these institutions and policies had long-lasting negative effects on Haiti's economy.

Later, both countries came under the rule of dictators: the Duvaliers in Haiti and Rafael Leónidas Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. Trujillo ruled with an iron fist from 1930 until his assassination in 1961.

Troops from the Dominican Republic massacred thousands of Haitian laborers living near the border in October 1937; an estimated 17,000 to 35,000 Haitians were killed in a single day. The Dominican Republic government agreed to compensate the surviving families the following year, but only partially lived up to that agreement.

The historical enmity between the two countries have stemmed from racist underpinnings. The Dominicans largely descended from European ancestry and have a Spanish culture. The Haitians, on the other hand are almost exclusively descendants of African slaves. Though the Dominican economy often depended on cheap Haitian labor, they tended to look down on their black neighbors.

In recent decades, the two nations have taken divergent paths, however, as the Dominican Republic has achieved significantly greater levels of political stability and economic growth than its neighbor.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Mann, Paul, Grenville Draper, and John F. Lewis. 1991. Geologic and tectonic development of the North America-Caribbean plate boundary in Hispaniola. Boulder, Colo: Geological Society of America. ISBN 0813722624

- Moya Pons, Frank. 1998. The Dominican Republic a national history. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 9781558761926

- Rogoziński, Jan. 1992. A brief history of the Caribbean: from the Arawak and the Carib to the present. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816024510

- San Miguel, Pedro Luis. 2005. The imagined island: history, identity, & utopia in Hispaniola. (Latin America in translation/en traducción/em tradução.) Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807829641

- Suárez, Lucía M. 2006. The tears of Hispaniola: Haitian and Dominican diaspora memory. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0813029260

- Online sources

- Corbett, Bob. October 27, 1995. Chronology of Haitian History World History Archives. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Geggus, David P. Making sense of the Haitian revolution Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- Guitar, Lynne. History of the Dominican Republic Hispaniola.com. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- Hutchinson, Sydney. Dominican Republic - background Merengue típico.

- Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia. 2007. Dominican Republic Microsoft Corporation. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Sagas, Ernesto. October 14-15, 1994. An Apparent Contradiction? - Popular Perceptions of Haiti and the Foreign Policy of the Dominican Republic Sixth Annual Conference of the Haitian Studies Association, Boston, MA. Webster University. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- U.S. Library of Congress. Dominican Republic: Occupation by the United States, 1916-1924 Retrieved October 15, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved January 9, 2018.

- Hispaniola Map. Google.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.