History of war

| War |

| History of war |

| Types of War |

| Civil war · Total war |

| Battlespace |

| Air · Information · Land · Sea · Space |

| Theaters |

| Arctic · Cyberspace · Desert Jungle · Mountain · Urban |

| Weapons |

| Armored · Artillery · Biological · Cavalry Chemical · Electronic · Infantry · Mechanized · Nuclear · Psychological Radiological · Submarine |

| Tactics |

|

Amphibious · Asymmetric · Attrition |

| Organization |

|

Chain of command · Formations |

| Logistics |

|

Equipment · Materiel · Supply line |

| Law |

|

Court-martial · Laws of war · Occupation |

| Government and politics |

|

Conscription · Coup d'état |

| Military studies |

|

Military science · Philosophy of war |

Military activity has been a constant process over thousands of years. However, there is little agreement about when it began. Some believe it has always been with us; others stress the lack of clear evidence for it in our prehistoric past, and the fact that many peaceful, non-military societies have and still do exist. Military history is composed of the events in the history of humanity that fall within the category of conflict. This may range from a melee between two tribes to conflicts between proper militaries to a world war affecting the majority of the human population. Military historians record (in writing or otherwise) the events of military history.

There are a number of ways to categorize warfare. One categorization is conventional versus unconventional, where conventional warfare involves well-identified, armed forces fighting one another in a relatively open and straightforward way without weapons of mass destruction. "Unconventional" refers to other types of war which can involve raiding, guerrilla, insurgency, and terrorist tactics or alternatively can include nuclear, chemical, or biological warfare.

Although many have sought to understand why wars occur, and thus to find peaceful solutions instead of armed conflicts leading to massive loss of life, wars have continued to plague humankind into the twenty-first century. Even when weapons capable of destroying all life on earth were invented, and placed in position ready for use, wars did not cease. No matter how many dead or injured return, or how many people say there should never be another war, another war has always erupted. The solution to the problem of war must be found deep within human nature. Only then will the possibility of a world of peace emerge.

Periods

The essential tactics, strategy, and goals of military operations have been unchanging throughout the past 5,000 years of our 90,000-year human history. As an example, one notable maneuver is the double envelopment or "pincer movement," considered to be the consummate military maneuver, executed by Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae in 216 B.C.E., over 2,200 years ago. This maneuver was also later effectively used by Khalid ibn al-Walid at the Battle of Walaja in 633 C.E., and was earlier described by the Chinese military theorist Sun Tzu, who wrote at roughly the same time as the founding of Rome.

By the study of history, the military seeks to not repeat past mistakes, and improve upon its current performance by instilling an ability in commanders to perceive historical parallels during battle, so as to capitalize on the lessons learned. The main areas military history includes are the history of wars, battles, and combats, history of the military art, and history of each specific military service.

One method of dividing such a massive topic is by cutting it into periods of time. While useful this method tends to be inaccurate and differences in geography mean there is little uniformity. What might be described as ancient warfare is still practiced in a number of parts of the world. Other eras that are distinct in European history, such as the era of Medieval warfare, may have little relevance in East Asia.

Prehistoric warfare

The beginning of prehistoric wars is a disputed issue between anthropologists and historians. In the earliest societies, such as hunter-gatherer societies, there were no social roles or divisions of labor (with the exception of age or sex differences), so every able person contributed to any raids or defense of territory.

In War Before Civilization, Lawrence H. Keeley, a professor at the University of Illinois, calculated that 87 percent of tribal societies were at war more than once per year, and some 65 percent of them were fighting continuously. The attrition rate of numerous close-quarter clashes, which characterize warfare in tribal warrior society, produced casualty rates of up to 60 percent.[1]

The introduction of agriculture brought large differences between farm workers' societies and hunter-gatherer groups. Probably, during periods of famine, hunters started to massively attack the villages of countrymen, leading to the beginning of organized warfare. In relatively advanced agricultural societies a major differentiation of roles was possible; consequently the figure of professional soldiers or militaries as distinct, organized units was born.

Ancient warfare

The first archaeological record, though disputed, of a prehistoric battle is about seven thousand years old, and it is located on the Nile in Egypt, in an area known as Cemetery 117. A large number of bodies, many with arrowheads embedded in their skeletons, indicates that they may have been the casualties of a battle.

Notable militaries in the ancient world included the Egyptians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks (notably the Spartans and Macedonians), Indians (notably the Magadhas, Gangaridais and Gandharas), Chinese (notably the Qins), Xiongnu, Romans, and Carthiginians. Egypt began growing as an ancient power, but eventually fell to the Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines and Arabs.

The fertile crescent of Mesopotamia was the center of several prehistoric conquests. Mesopotamia was conquered by the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians and Persians. Iranians were the first nation who introduced cavalry into their army.[2]

The earliest recorded battle in India was the Battle of the Ten Kings. The Indian epics Mahabharata and Ramayana are centered around conflicts and refer to military formations, theories of warfare and esoteric weaponry. Chanakya's Arthashastra contains a detailed study on ancient warfare, including topics on espionage and war elephants. Alexander the Great invaded Northwestern India and defeated King Porus in the Battle of the Hydaspes River. The same region was soon conquered by Chandragupta Maurya after defeating the Macedonians and Seleucids. He also went on to conquer the Nanda Empire and unify Northern India. Most of Southern Asia was unified under his grandson Ashoka the Great after the Kalinga War, though the empire collapsed not long after his reign.

In China, the Shang Dynasty and Zhou Dynasty had risen and collapsed. This led to a Warring States Period, in which several states continued to fight with each other over territory. Confucius and Sun Tzu wrote various theories on ancient warfare (as well as international diplomacy). The Warring States era philosopher Mozi (Micius) and his Mohist followers invented various siege weapons and siege crafts, including the Cloud Ladder (a four-wheeled, protractable ramp) to scale fortified walls during a siege of an enemy city. China was first unified by Qin Shi Huang after a series of military conquests. His empire was succeeded by the Han Dynasty, which later came into conflict with the Xiongnu, and collapsed into an era of continuous warfare during the Three Kingdoms period.

The Achaemenid Persian Empire was founded by Cyrus the Great after conquering the Median Empire, Neo-Babylonian Empire, Lydia and Asia Minor. His successor Cambyses went onto conquer the Egyptian Empire, much of Central Asia, and parts of Greece, India and Libya. The empire later fell to Alexander the Great after defeating Darius III. After being ruled by the Seleucid dynasty, the Persian Empire was subsequently ruled by the Parthian and Sassanid dynasties, which were the Roman Empire's greatest rivals during the Roman-Persian Wars.

In Greece, several city-states emerged to power, including Athens and Sparta. The Greeks successfully stopped two Persian invasions, the first at the Battle of Marathon, where the Persians were led by Darius the Great, and the second at the Battle of Salamis, a naval battle where the Greek ships were deployed by orders of Themistocles and the Persians were under Xerxes I, and the land engagement of the Battle of Plataea. The Peloponnesian War then erupted between the two Greek powers Athens and Sparta. Athens built a long wall to protect its inhabitants, but the wall helped to facilitate the spread of a plague that killed about 30,000 Athenians, including Pericles. After a disastrous campaign against Syracuse, the Athenian navy was decisively defeated by Lysander at the Battle of Aegospotami.

The Macedonians, under Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great, invaded Persia and won several major victories, establishing Macedonia as a major power. However, following Alexander's death at an early age, the empire quickly fell apart.

Meanwhile, Rome was gaining power, following a rebellion against the Etruscans. At the three Punic Wars, the Romans defeated the neighboring power of Carthage. The First Punic War centered around naval warfare over Sicily; after the Roman development of the corvus, the Romans were able to board Carthaginian ships. The Second Punic War started with Hannibal’s invasion of Italy by crossing the Alps. He famously won the encirclement at the Battle of Cannae. However, after Scipio invaded Carthage, Hannibal was forced to follow and was defeated at the Battle of Zama, ending the role of Carthage as a power. The Third Punic War was a failed revolt against the Romans.

In 54 B.C.E. the Roman triumvir Marcus Licinius Crassus took the offensive against the Parthian Empire in the east. In a decisive battle at Carrhae Romans were defeated and the golden Aquila (legionary battle standards) was taken as trophy to Ctesiphon. The result was one of the worst defeats suffered by the Roman Republic in its entire history. Romans after this defeat learnt the importance of cavalry from Iranians and introduced it into their army, just as nearly a thousand year earlier the first Iranian to reached the Iranian Plateau introduced the Assyrians to a similar reform.[3]

Rome quickly took over the Greeks and were expanding into Gaul, winning battles against the barbarians. By the time of Marcus Aurelius, the Romans had expanded to the Atlantic Ocean in the west to Mesopotamia in the east. However, Aurelius marked the end of the Five Good Emperors, and Rome quickly fell to decline. The Huns, Goths, and other barbaric groups invaded Rome, which continued to suffer from inflation and other internal strifes. Despite the attempts of Diocletian, Constantine I, and Theodosius I, western Rome collapsed. The Byzantine empire continued to prosper, however.

Medieval warfare

When stirrups came into use some time during the Dark Ages, militaries were forever changed. This invention coupled with technological, cultural, and social developments had forced a dramatic transformation in the character of warfare from antiquity, changing military tactics and the role of cavalry and artillery. Similar patterns of warfare existed in other parts of the world. In China around the fifth century armies moved from massed infantry to cavalry based forces, copying the steppe nomads. The Middle East and North Africa used similar, if often more advanced, technologies than Europe. In Japan the Medieval warfare period is considered by many to have stretched into the nineteenth century. In Africa along the Sahel and Sudan states like the Kingdom of Sennar and Fulani Empire employed Medieval tactics and weapons well after they had been supplanted in Europe.

In the Medieval period, feudalism was firmly implanted, and there existed many landlords in Europe. Landlords often owned castles which they used to protect their territory.

The Islamic Arab Empire began rapidly expanding throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia, initially led by Khalid ibn al-Walid, and later under the Umayyads, expanded to the Iberian Peninsula in the west and the Indus Valley in the east. The Abassids then took over the Arab Empire, though the Umayyads remained in control of Islamic Spain. At the Battle of Tours, the Franks under Charles Martel stopped short a Muslim invasion. The Abassids defeated the Tang Chinese army at the Battle of Talas, but were later defeated by the Seljuk Turks and the Mongols centuries later, until the Arab Empire eventually came to an end after the Battle of Baghdad in 1258.

In China, the Sui Dynasty had risen and conquered the Chen Dynasty of the south. They invaded Vietnam (northern Vietnam had been in Chinese control since the Han Dynasty), fighting the troops of Champa, who had cavalry mounted on elephants. The Sui collapsed and was followed by the Tang Dynasty, who fought with various Turkish groups, the Tibetans of Lhasa, the Tanguts, the Khitans, and collapsed due to political fragmentation of powerful regional military governors (jiedushi). The innovative Song Dynasty followed next, inventing new weapons of war that employed the use of Greek Fire and gunpowder (see section below) against enemies such as the Jurchens. The Mongols under Genghis Khan, Ogodei Khan, Mongke Khan, and finally Kublai Khan later invaded and eventually defeated the Chinese Song Dynasty by 1279. The Mongol Empire continued to expand throughout Asia and Eastern Europe, but following the death of Kublai Khan, it fell apart.

Gunpowder warfare

After Gunpowder weapons were first developed in Song Dynasty China, the technology later spread west to the Ottoman Empire, from where it spread to the Safavid Empire of Persia and the Mughal Empire of India. The arquebus was later adopted by European armies during the Italian Wars of the early sixteenth century. This all brought an end to the dominance of armored cavalry on the battlefield. The simultaneous decline of the feudal system — and the absorption of the medieval city-states into larger states — allowed the creation of professional standing armies to replace the feudal levies and mercenaries that had been the standard military component of the Middle Ages. The period spanning between the 1648 Peace of Westphalia and the 1789 French Revolution is also known as Kabinettskriege (Princes' warfare) as wars were mainly carried out by imperial or monarchic states, decided by cabinets and limited in scope and in their aims. They also involved quickly shifting alliances, and mainly used mercenaries.

Some developments of this period include field artillery, battalions, infantry drill, dragoons, and bayonets.

Industrial warfare

As weapons—particularly small arms—became easier to use, countries began to abandon a complete reliance on professional soldiers in favor of conscription. Conscription was employed in industrial warfare to increase the amount of soldiers that were available for combat. This was used by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Napoleonic Wars. Technological advances became increasingly important; while the armies of the previous period had usually had similar weapons, the industrial age saw encounters such as the Battle of Sadowa, in which possession of a more advanced technology played a decisive role in the outcome.

Total war was used in industrial warfare, the objective being to prevent the opposing nation from being able to engage in war. During the American Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman's "March to the Sea" and Philip Sheridan's burning of the Shenandoah Valley are examples of total warfare.

Modern warfare

In modern times, war has evolved from an activity steeped in tradition to a scientific enterprise where success is valued above methods. The notion of total war is the extreme of this trend. Militaries have developed technological advances rivaling the scientific accomplishments of any other field of study.

However, it should be noted that modern militaries benefit in the development of these technologies under the funding of the public, the leadership of national governments, and often in cooperation with large civilian groups. As for "total war," it may be argued that it is not an exclusive practice of modern militaries, but in the tradition of genocidal conflict that marks even tribal warfare to this day. What distinguishes modern military organizations from those previous is not their willingness to prevail in conflict by any method, but rather the technological variety of tools and methods available to modern battlefield commanders, from submarines to satellites, and from knives to nuclear warheads.

World War I was sparked by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, leading to the mobilization of Austria and Serbia. The Germans joined the Austrians to form the Central powers; the French, British, and Russians formed the Allied powers. Following the Battle of the Marne and the outflanking attempt of both nations in the "Race to the Sea," trench warfare ensued, leaving the war in a great deadlock. Major operations by the Germans at the Battle of Verdun and by the British and the French at the Battle of the Somme were carried out, and new technology like tanks and chlorine gas were used. Following the USA's entrance into the war, the Germans and their allies were eventually defeated.

World War II ensued after Germany's invasion of Poland, forcing Britain and France to declare war. The Germans quickly defeated France and Belgium. A hasty evacuation occurred at Dunkirk to save the British army from complete disaster. The Germans then attacked Russia and marched to take over the Russian resources, but were thwarted. Meanwhile, Japan had launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, leading the United States to join the Allied powers. In Europe, the Allies opened three fronts: in the west, after securing Normandy; in the east, aiding Russia; and in the south, through Italy. Germany eventually surrendered, allowing the Allies to turn and focus on the war in the Pacific, where the Naval troops took one island at a time island hopping. The dropping of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki led to the surrender of Japan and the end of the Second World War.

The Cold War then emerged, reaching the climax at the Cuban Missile Crisis. Hostilities never actually occurred, though the US did engage against communist states in the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

Conflicts following the Cold War have been increasingly smaller and unconventional. There have been a few philosophies to emerge. The first, advocated by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld involved emphasis on technological prowess and expensive weaponry to minimize the manpower needed to fight warfare. The second tact has been the guerrilla warfare adopted by terrorists and other stateless fighters, involving hit and run tactics designed to harass and weaken an enemy. A third philosophy is that of "armed social work," which involves armies gaining the support of the local population in whatever region the conflict is taking place.[4] This approach mitigates the threat of guerrilla and terrorist tactics as smaller units of fighters have nowhere to hide and have effectively steeled the local population into supporting another force.

Technological evolution

New weapons development can dramatically alter the face of war.

Prehistory

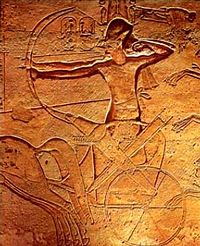

In prehistoric times, fighting occurred by usage of clubs and spears, as early as 35,000 B.C.E. Arrows, maces, and slings were developed around 12,000 B.C.E. Chariots, pulled by animals like the onager, ox, donkey, and later the horse, originated around 2,000 B.C.E.[5] The chariot was an effective weapon for speed; while one man controlled the maneuvering of the chariot, a second bowman could shoot arrows at enemy soldiers. These became crucial to the maintenance of several governments, including the New Egyptian Kingdom and the Shang dynasty.

Ancient warfare

In the next phase, the infantry would become the core of military action. The infantry started as opposing armed groups of soldiers underneath commanders. The Greeks used rigid, heavily-armed phalanxes, but the Romans used mobile legions that were easily maneuverable.

Cavalry would subsequently become an important tool. In the Sicilian Expedition, led by Athens in an attempt to subdue Syracuse, the well-trained Syracusan cavalry became crucial to the success of the Syracusans. Macedonian Alexander the Great effectively deployed his cavalry forces to secure victories. In later battles, like the Battle of Cannae of the Second Punic War, the importance of the cavalry would be repeated. Hannibal was able to surround the Romans on three sides and encircled them by sending the cavalry to the rear of the army. There were also horse archers, who had the ability to shoot on horseback- the Mongols were especially fearsome with this tactic. In the Middle Ages, armored cataphracts continued to fight on horseback. Even in the First World War, cavarly was still considered important; the British mobilized 165,000 horses, the Austrians 600,000, the Germans 715,000, and the Russians more than a million.[6]

The early Indo-Iranians developed the use of chariots in warfare. The scythed chariot was later invented in India and soon adopted by the Persian Empire.

War elephants were often deployed for fighting in ancient warfare. They were first used in India and later adopted by both the Persians and Alexander the Great against one another. War elephants were also used in the Battle of the Hydaspes River, and by Hannibal in the Second Punic War against the Romans.(The effectiveness of war elephants in a battle is a matter of debate)

There were also organizational changes, made possible by better training and intercommunication. Combined arms was the concept of using infantry, cavalry, and artillery in a coordinated way. The Romans, Swiss, and others made advances with this, which arguably led to them being unbeatable for centuries.

Fortifications are important in warfare. Early hill-forts were used to protect inhabitants in the Iron Age. They were primitive forts surrounded by ditches filled with water.[7] Forts were then built out of mud bricks, stones, wood, and other available materials. Romans used rectangular fortresses built out of wood and stone. As long as there have been fortifications, there have been contraptions to break in, dating back to the times of Romans and earlier. Siege warfare is often necessary to capture forts.

Bows and arrows were often used by combatants. Egyptians shot arrows from chariots effectively. The crossbow was developed around 500 B.C.E. in China, and was used a lot in the Middle Ages.[8] The English/Welsh longbow from the 12th century also became important in the Middle Ages. It helped to give the English a large early advantage in the Hundred Years' War, even though the English were eventually defeated. It dominated battlefields for over a century.

Guns

In the tenth century, the invention of gunpowder led to many new weapons that were improved over time. Blackpowder was used in China since the fourth century, but it was not used as a weapon until the 11th century. Until the mid-fifteenth century, guns were held in one hand, while the explosive charge was ignited by the other hand. Then came the matchlock, which was used widely until around the 1720s. Leonardo da Vinci made drawings of the wheel lock which made its own sparks. Eventually, the matchlock was replaced by the flintlock. Cannons were first used in Europe in the early fourteenth century, and played a vital role in the Hundred Years' War. The first cannons were simply welded metal bars in the form of a cylinder, and the first cannonballs were made of stone. By 1346, at the battle of Crécy, the cannon had been used; at the Battle of Agincourt they would be used again.[9]

The Howitzer, a type of field artillery, was developed in seventeenth century to fire high trajectory explosive shells at targets that could not be reached by flat trajectory projectiles.

Bayonets also became of wide usage to infantry soldiers. Bayonet is named after Bayonne, France where it was first manufactured in the sixteenth century. It is used often in infantry charges to fight in hand-to-hand combat. General Jean Martinet introduced the bayonet to the French army. They have continued to be used, for example in the American Civil War.

At the end of the eighteenth century, iron-cased rockets were successfully used militarily in India against the British by Tipu Sultan of the Kingdom of Mysore during the Anglo-Mysore Wars. Rockets were generally inaccurate at that time, though William Hale, in 1844, was able to develop a better rocket. The new rocket no longer needed the rocket stick, and had a higher accuracy.

In the 1860s there were a series of advancements in rifles. The first repeating rifle was designed in 1860 by a company bought out by Winchester, which made new and improved versions. Springfield rifles arrived in the mid-nineteenth century also. Machine guns arrived in the middle of the nineteenth century. Automatic rifles and light machine guns first arrived at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Naval warfare was often crucial to military success. Early navies used sailing ships without cannons; often the goal was to ram the enemy ships and cause them to sink. There was human oar power, often using slaves, built up to ramming speed. Galleys were used in the third millennium B.C.E. by the Cretans. The Greeks later advanced these ships. In 1210 B.C.E., the first recorded naval battle was fought between Suppiluliuma II, king of the Hittites, and Cyprus, which was defeated. In the Persian Wars, the navy became of increasing importance. Triremes were involved in more complicated sea-land operations. Themistocles helped to build up a stronger Greek navy, composed of 310 ships, and defeated the Persians at the Battle of Salamis, ending the Persian invasion of Greece.[10] In the First Punic War, the war between Carthage and Rome started with an advantage to Carthage because of their naval experience. A Roman fleet was built in 261 B.C.E., with the addition of the corvus that allowed Roman soldiers onboard the ships to board the enemy ships. The bridge would prove effective at the Battle of Mylae, resulting in a Roman victory. The Vikings, in the eighth century C.E., invented a ship propelled by oars with a dragon decorating the prow, hence called the Drakkar.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the first European fire ships were used. Ships were filled with flammable materials, set on fire, and sent to enemy lines. This tactic was successfully used by Francis Drake to scatter the Spanish Armada at the Battle of Gravelines,[11] and would later be used by the Chinese, Russians, Greeks, and several other countries in naval battles. Naval mines were invented in the seventeenth century, though they were not used in great numbers until the American Civil War. They were used heavily in the First World War and Second World War.

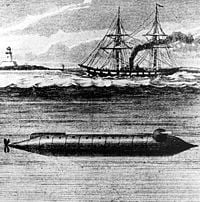

The first model of submarine was invented in 1624 by Cornelius Drebbel, which could go to depth of 15 feet (5 m). However, the first war submarine as we presently think of it was constructed in 1885 by Isaac Peral.

The Turtle was developed by David Bushnell during the American Revolution. Robert Fulton then improved the submarine design by creating the Nautilus (submarine).[12]

Also in the 1860s came the first boats that would later be known as torpedo boats. These were first used in the American Civil War, but generally were not successful. Several Confederates used spar torpedoes, which were bombs on long poles designed to attach to boats. In the later part of the 19th century, the self-propelled torpedo was developed. The HNoMS Rap

Air warfare

On December 17, 1903, the Wright Brothers performed the first controlled, powered, heavier-than-air flight; it went 39 meters (120 ft). In 1907, the first helicopter flew, but it wasn't practical for usage. Aviation became important in World War I, in which several aces gained fame. In 1911 an aircraft took off from a warship for the first time. It was a cruiser. Take-offs were soon perfected, but deck landings on a cruiser were another matter. This led to the development of an aircraft carrier with a decent unobstructed flight deck.

Balloons were first used in warfare at the end of the eighteenth century. It was first introduced in Paris of 1783; the first balloon traveled over 5 miles (8 km). Previously military scouts could only see from high points on the ground, or from the mast of a ship. Now they could be high in the sky, signaling to troops on the ground. This made it much more difficult for troop movements to go unobserved.

Modern warfare

Chemical warfare exploded into the public consciousness in World War I but may have been used in earlier wars without as much human attention. The Germans used gas-filled shells at the Battle of Bolimov on January 3, 1915. These were not lethal, however. In April 1915, the Germans developed a chlorine gas that was highly lethal, and used it to great effect at Second Battle of Ypres.[13]

At the start of the World Wars, various nations had developed weapons that were a surprise to their adversaries, leading to a need to learn from this, and alter how to combat them. Flame throwers were first used in the first world war. The French were the first to introduce the armored car in 1902. Then in 1918, the British produced the first armored troop carrier. Many early tanks were proof of concept but impractical until further development. In World War I, the British and French held a crucial advantage due to their superiority in tanks; the Germans had only a few dozen A7V tanks, as well as 170 captured tanks. The British and French both had over several hundred each. The French tanks included the 13 ton Schnedier-Creusot, with a 75 mm gun, and the British had the Mark IV and Mark V tanks.[14]

World War II gave rise to even more technology. The worth of the aircraft carrier was proved in the battles between the United States and Japan like the Battle of Midway. Radar was independently invented by the Allies and Axis powers. It used radio waves to detect nearby objects. Molotov cocktails were invented by the Finns in 1939, during the Winter War. The atomic bomb was developed by the Manhattan Project and launched at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, ultimately ending World War II.

During the Cold War, even though fighting did not actually occur, the superpowers- the United States and Russia- engaged in a race to develop and increase the level of technology available for military purposes. In the space race, both nations attempted to launch human beings into space to the moon. Other technological advances centered around intelligence (like the spy satellite) and missiles (ballistic missiles, cruise missiles). Nuclear submarine, invented in 1955. This meant submarines no longer had to surface as often, and could run more quietly. They evolved into becoming underwater missile platforms. Cruise missiles were invented in Nazi Germany during World War II in the form of the V-1.

Following the Cold War, there has been a de-emphasis on maintaining large standing armies capable of large scale warfare. Wars are now fought on a conflict-to-conflict, smaller scale basis rather than with overwhelming force. This means precise, reliable technologies are more important than simply being able to throw line after line of tanks or infantry at an enemy. Also, there is less of an emphasis on the violent side of warfare and more focus on the cerebral aspects such as military intelligence and psychological warfare, which enable commanders to fight wars on a less violent scale, with the idea of preventing needless loss of life.

Historiography

Gaining an accurate assessment of past military encounters may prove difficult because of bias, even in ancient times, and systematic propaganda in more modern times. Descriptions of battles by leaders may be unreliable due to the inclination to minimize mention of failures and exaggerate when boasting of successes. Further, military secrets may prevent some salient facts from being reported at all; scholars still do not know the nature of Greek fire, for instance. Despite these limitations, wars are some of the most studied and detailed periods of human history.

Significant events such as major battles and conquests tend to be recorded in writing, in epics such as the Homeric writings pertaining to the Trojan War, or even personal writings. The earliest recorded stories center around warfare, as war was both a common and dramatic aspect of life; the witnessing of a major battle involving thousands of soldiers would be quite a spectacle, even today, and thus considered worthy both of being recorded in song and art. Realistic histories were written that described the men and events that led to changes in culture, language, technology and lifestyles, as well as being a central element in fictional works. As nation-states evolved and empires grew, the increased need for order and efficiency lead to an increase in the number of records and writings. Officials and armies would have good reason for keeping detailed records and accounts involving all aspects of matters such as warfare that—in the words of Sun Tzu—was "a matter of vital importance to the state."

Weapons and armor, designed to be sturdy, tended to last longer than other artifacts, and thus a great deal of surviving artifacts recovered tend to fall in this category as they are more likely to survive. Weapons and armor were also mass-produced to a scale that makes them quite plentiful throughout history, and thus more likely to be found in archaeological digs. Such items were also considered signs of posterity or virtue, and thus were likely to placed in tombs and monuments to prominent warriors. And writing, when it existed, was often used for kings to boast of military conquests or victories.

Notes

- ↑ Lawrence Keeley, War Before Civilization, (Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0195119126)

- ↑ Suren Pahlav Suren-Pahlav S., General Surena; The Hero of Carrhae (originally published by CAIS at SOAS.com) Iran Chamber. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ↑ Pahlav Suren-Pahlav S., General Surena; The Hero of Carrhae

- ↑ MARK KUKIS Looking the Other Way December 6, 2006, TIME. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ↑ David W. Anthony, "The origin of the true chariot. (September 1995). Extract from David W. Anthony. "Horse, wagon & chariot: Indo-European languages and archaeology." Antiquity

- ↑ John Keegan. The First World War. New York: Random House, 1999), 73 and Chapter 4: The Battle of the Frontiers and the Marne

- ↑ TIMEREF.COM The Medieval Castle. Accessed May 16, 2006.

- ↑ Stephen Selby, (2001). A Crossbow Mechanism with Some Unique Features from Shandong, China. Accessed on May 17, 2006.

- ↑ J.B. Calvert, (February 19, 2006) Cannons and Gunpowder. www.du.edu. Accessed on May 18, 2006.

- ↑ Martijn Moerbeek. (January 21, 1998). The battle of Salamis, 480 B.C.E. www.monolith.dnsalias.org. Accessed May 16, 2006.

- ↑ Jorge. The "Invincible" Armada. Accessed on May 18, 2006.

- ↑ Early Underwater Warfare. California Center for Military History. Accessed on May 18, 2006.

- ↑ Keegan, 197-199

- ↑ Keegan, 410

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fry, Douglas P. 2005. The Human Potential for Peace: An Anthropological Challenge to Assumptions about War and Violence. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195181786

- Keegan, John. 1999. The First World War. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0375400520

- Keeley, Lawrence.1997. War Before Civilization. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195119126

- Kelly, Raymond C. 2000 Warless Societies and the Origin of War. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472097385

- Otterbein, Keith. 2004. How War Began. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1585443301

External links

All links retrieved January 11, 2018.

- Military History Encyclopedia HistoryOfWar.org.

- Military History Podcast

- Military and Service Magazines of the World's Forces, World War 2 www.neval-history.net.

- U.S. Army Center for Military History (CMH)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.